NOTE: I finished this article several weeks ago, before the current COVID-19 disaster gave new urgency and recognition to the term “essential personnel.” It’s clear to everyone now how great a role is played by grocery workers, truckers, gas station clerks and, of course, medical personnel, in keeping our society going. We depend daily on the courage and selflessness of the men and women who keep the flow of goods and services moving, who assure the reliability of energy to light our homes and keep us warm, who put food on our tables. And yes, as Dave Baker said decades ago, who make sure there’s water in the taps and the sewage flows downhill.

To ALL of you who are so often taken for granted and whose skills and dedication and integrity are essential to our survival, we say thanks and God bless you…JS.

Every few years, the highest branches of the federal government discover that their loathing for each other is even greater than usual, and in a fit of pique, rather than just holding their breaths until they all collectively pass out, the Congress and President decide to quit funding the very government they oversee. This results in the spontaneous “laying off” of millions of federal employees, from coast to coast and around the world.

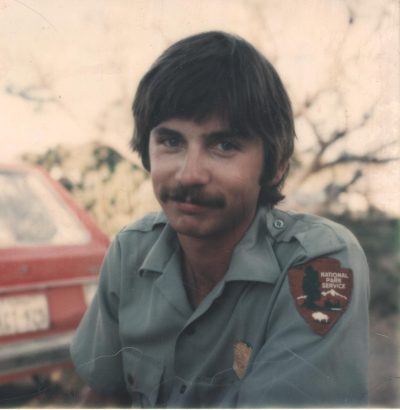

This shutdown has occurred several times in past decades. Once while I was a ranger at Arches, we came within hours of closing the park, before President Reagan and the Congress secured another unsteady truce. Our supervisors instructed us back then, as they do now, that only “essential” staff would remain on duty. Otherwise, we would all be laid off for the duration.

During our shutdown threat, I asked my boss if I was “essential” to the park. After he had stopped laughing and composed himself, Jerry shook his head and advised me to go away for a while. The park would be fine.

But here was the cold, hard, unvarnished, bitter truth. While I knew I couldn’t begin to argue that my contribution to Arches National Park was “essential” to its well-being, neither in all honesty, could my boss. Like me, the chief ranger could have gone on vacation and never returned and few would have noticed.

The same could be said of the park naturalists. Oh sure, they could tell the difference between a marbled godwit and a long-billed curlew, and could explain to the tourists how eriogonum inflatum growing on the flanks of Mancos Shale hillsides looks like elephant hair.

But was it essential? Even we who were duly authorized law enforcement rangers could never really make an honest argument for our indispensability. Few of us wanted to be ranger cops to begin with, and our training for the job was minimal. (See my previous law enforcement story.) There was a greater chance we’d shoot ourselves in the foot than effectively stop the commission of a dastardly deed. The tourists were probably safer when we were asleep.

No…there is only one component of the National Park Service work force that the world could not live without. At any given federally-funded unit that involves the management and care of public lands, you can fire the rangers, kidnap the administrators, deport the managers, incarcerate the cops..hell you could send the Secretary of Interior to Lower Slovenia, and hardly anyone would notice or care. Some might even celebrate.

But get rid of the park maintenance crew? Pandemonium would ensue. Panic on an unprecedented scale. If it happened right now, tourists would be so distracted we’d forget we’d ever heard of COVID-19.

The park maintenance staff are the REAL naturalists because, for starters, they are the key to keeping the parks natural. Without them, we’d be unable to see the vistas over the garbage. Once it was decided that the role of the National Park Service was to include building roads and trails and creating easy access to these natural wonders for humans, and constructing facilities to accommodate the physical and biological needs of those hordes, the effect was inevitable. Park Maintenance is essential. Or it should be.

There’s another reason why the maintenance staff were better naturalists than the rest of us. At least in those days, they were far better at surviving in Nature than we were.

Most of the men who occupied those jobs—and they were mostly men in those days—were trained to be cowhands, miners and prospectors, truck drivers, mechanics, heavy equipment operators, plumbers and carpenters. In short, they knew how to fix things. And most of them were veterans of the Great Depression, World War II, or Korea, had lived rough, and knew how to take care of themselves. They were common sense guys and not driven by ideology. I admired that quality in them. At the time, I was a kid with a diploma, but not much practical life experience. Life was a theory. When I look back at those days, I realize how much they became my mentors.

At Arches National Park, the maintenance staff changed some over the years, but not much. Moab was home and their loyalties were to the place, not the agency. Most of them had lived in the area for decades. Many had come for the uranium boom and stayed on after the bust. A few had even journeyed to Utah as young “CCC Boys,” in the late 1930s, then served in the war, but came back to live in southeast Utah when it was over.

When I think of the maintenance division, I remember many great people, but three stand out in my mind and memory. And my recollections of those men are what this story is really about— Dave Baker, Carroll Clark, and Rocky Newell. They don’t make them like that any more.

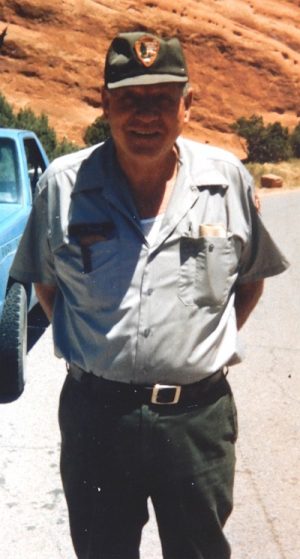

DAVE BAKER…

Dave Baker was the Arches Chief of Maintenance for twenty years. He used to remind me on a regular basis that, while we rangers got to wear the smoky hat and a badge, there were really only two things that mattered to the tourists.

“They want the garbage picked up and they want to know that the shit always flows downhill. That’s it.”

And he was right, of course. Nothing irked the tourists more, or me, than a backed up toilet. And the occasions when Dave felt his proudest of me was when I resolved issues like that on my own, without calling him. It was Dave who suggested I store an extra heavy duty coat hanger in the park patrol car for just such septic catastrophes. (I had at least already figured out how to jiggle the handle.)

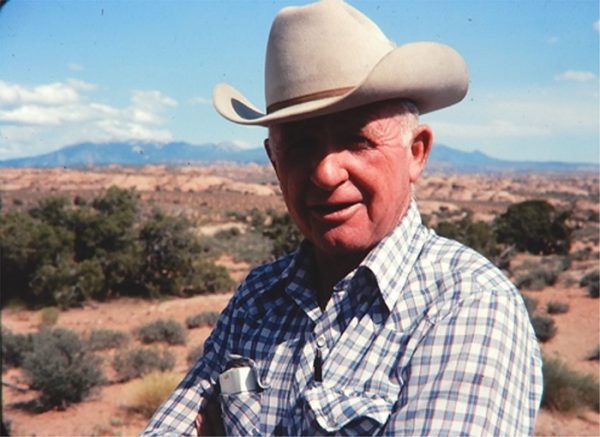

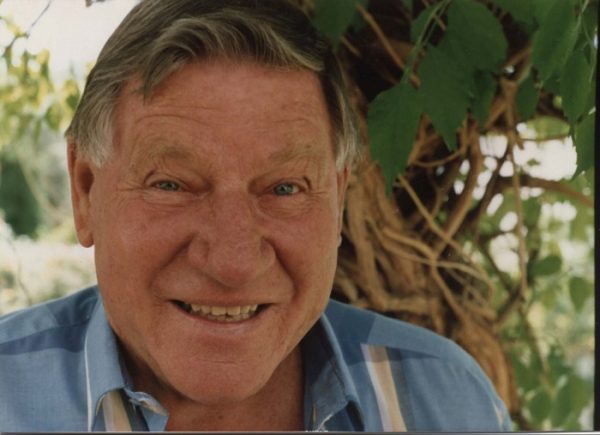

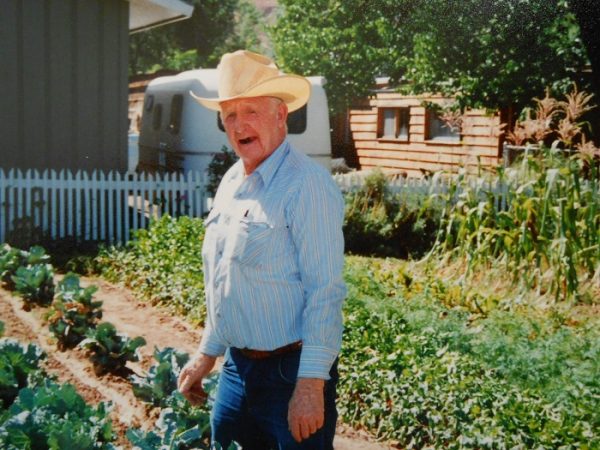

Sometimes, I’d ride with Dave to do trash collection and to this day I regret that I didn’t have a tape recorder with me to preserve some of his memories. He may have worked for the Park Service for 25 years, but in fact he was a cowboy right down to his heart and soul. He was born and raised on a ranch near De Beque, Colorado, on Conn Creek, that had been homesteaded by his grandfather. He was throwing hay bales and mending fences and training horses for as long as he could remember. Dave married Shirley in 1945 and continued to cowboy on a ranch near De Beque but they came to Moab in 1949 and stayed.

On our drives, Dave would talk about those times and he often mentioned that first winter. He would say, “Well… we come to the country in ’49, and it was cold. The snow was ass-deep to a tall Indian.” At other times he’d substitute “tall Mormon Bishop,” depending on his mood. Recently, just to make sure my memory was correct, I checked the weather forecasts and sure enough, the winter of 1949 was bitter cold and marked by many blizzards and storms. Dave’s memory was spot on.

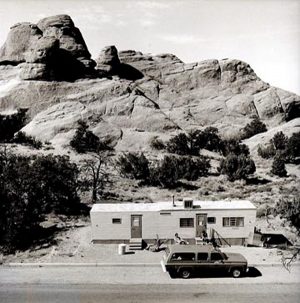

I had met him the year before I came to work as a ranger. In the last week of October 1974, I was camped at the Devils Garden campground and the weather had turned cold and blustery. Muckluk and I had the campground entirely to ourselves in site #2, just fifty yards from the trailer that would become home in 18 months. At the time, of course, I had no idea.

Three months earlier, a close friend of mine had been killed suddenly in a terrible crash on the Kentucky Turnpike near Louisville. It was the first death of someone my age I had ever experienced and all these weeks later, I was still reeling from it.

While I was camped, the maintenance pickup came through the campground, with Dave Baker behind the wheel. The Devils Garden was quiet, Dave had some time, and I was in search of someone to talk to. For the next few days, Dave and I had long conversations, though mostly I purged and he listened. He was that rare man who really did know how to listen. His quiet compassion meant a lot to me. At the end of the week, I headed back to Kentucky, thinking I’d never see him again.

But a year later, Jerry Epperson had hired me as a volunteer and on my first day, Dave walked into the visitor center, saw me and stopped. I asked him if he remembered me and he said, “You’re that young fella who lost the gal…how’re you doing?”

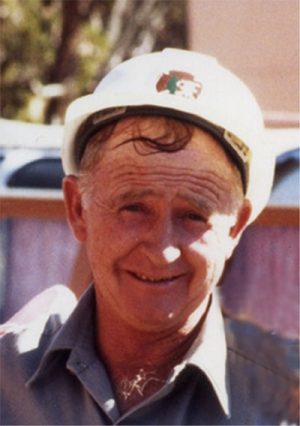

Dave was one of those men who could tolerate bullshit, but certainly had no use for it. Working for a branch of the federal government sometimes frustrated him almost to tears. My own frustrations often gave both of us plenty to commiserate over. One day, the Guys came by the trailer for lunch as they often did. Dave took off his hardhat, tossed it on a chair and said, “Well, you’re not gonna believe what they want me to do now.”

“Who’s they, Dave?”

He just gave me the Baker Scowl. I would have given a month’ s pay to perfect that glare. (Far easier than all the words I type hoping to achieve the same goal.) Finally Dave explained….

A few months earlier, someone in the federal government had decided that all those magnificent routed wood signs that were such iconic features of national parks had become inadequate. A panel of experts had concluded that the signs weren’t “readable enough” to meet new highway standards. Across the country, there were thousands of these signs; in Arches, at least 30 or 40 would need to be replaced.

The new signs were made by the 3M Corporation and carried the “ScotchCal” brand. They were, of course, much larger than the old signs and the lettering was made of a highly reflective material. Supposedly the new signs were maintenance-free and were mounted on tubular steel posts. Additionally there were very specific parameters that must be adhered to, regarding their height and distance from the road’s edge.

The new signs arrived. Six months late, of course. Baker grumbled a bit about the silliness of it all. (“There wasn’t a goddamn thing wrong with them old signs, but what the hell.”) But slowly he and his crew yanked out the old routed signs and installed the Scotchcals. They were hideously ugly by comparison. But they did have reflective qualities!

The maintenance team took the old signs down to the park “boneyard,” and some of us salvaged a few of them for posterity. As they removed the old signs, the team dutifully installed the new ones. At least, Dave thought, he wouldn’t have to paint the damn things. After all they were “maintenance-free.”

So now, here was Dave, at the trailer, chewing slowly on a sandwich, and explaining his latest frustration…

“So what is it,” I asked Dave, “that they want you to do?”

Dave shook his head and sort scowled at the world. “Okay…you know these signs we just put up, right? They came pre-painted, the letters are on there already, The backs of the signs are painted dark brown and the posts are made out of that steel that rusts so it looks ‘natural.'”

Dave always smirked when he used the word ‘natural.’ I nodded.

“All we had to do was dig the holes and put in the signs and we’d be done.” Dave did The Scowl again.

“Well now, they want us to go and paint the back of every damn sign that we just put in. Every damn one of them. And the posts too. They want us to paint the rusty steel posts. But not ALL of the post. They want us to paint the post right down to where the bottom of the sign is. So they want us to paint all of the sign backs and part of the poles…what the hell sense does that make?”

I made the mistake of asking what color they wanted him to paint the backs of the signs. And while Dave looked like he might blow a gasket, keep in mind he never raised his voice a decibel. Ever. No matter how aggravated he might be. He had a way of yelling quietly, and it was far more effective.

“Oh,” Dave rolled his eyes. “That’s the best part. They want us to paint all of them ‘desert rose.’ Every damn sign ‘desert rose.'”

“And half the poles?”

“Yep…half the goddamn poles.”

The color ‘desert rose’ was also a tint commonly used by the Park Service. It wasn’t quite pink and it wasn’t tan. It was somewhere in between. My trailer was “desert rose.’ It looked pink to me. The sign backs, in their original dark shade, were hardly noticeable coming from the other direction, which seemed a lot more ‘natural’ to most of us. But the edict had come down that they would all be re-painted. And they were.

Ultimately Baker decided he “didn’t give a goddamn,” and as he noted, “I get paid the same wage whether we paint them or not. And I reckon if that means we don’t have time to get the trash or clean the toilets, that’ll just be too damn bad.”

Of course, Dave wasn’t like that. He would never have left a job undone. And while he may have loathed the inefficiency of the government on a daily basis, I never saw it get the best of him. When he got really aggravated, he’d just fall back on his stories. “Did I ever tell you about the summer of ’47, up there in the Roans?”

And he never carried a grudge or kept it personal. He might have been aggravated to distraction, but then Dave would lean back and say, “Well…otherwise, I guess he’s a pretty good old boy (or gal, as the case might be).”

A decade after he retired, Dave sat down with historian Jean McDowell to do an oral history for the Moab Museum and he put it in perspective. He told Jean, “I put in twenty-six years with the Park. And I enjoyed most of it, but I was glad to be away from it. It’s a bureaucratic deal that gets worse as time goes on, too.”

Classic Dave Baker understatement.

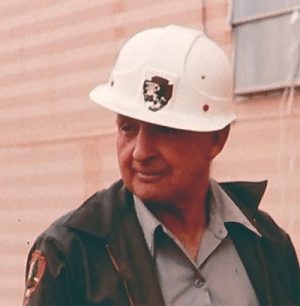

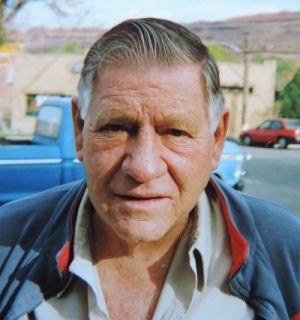

CARROLL CLARK…

Dave’s second in command was Carroll Clark. Carroll had been born far out on the High Plains in a tiny town called Kim, Colorado, but he and his wife Ginger and family had lived in Moab for many years. They owned one of the beautiful orchards along Fifth West and Carroll often brought up some fruit for the seasonals.

Like so many men who wound up in Moab, Carroll had worked a variety of jobs, from truck driver to mechanic and, of course, he had once been employed by Charlie Steen.

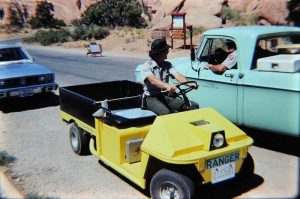

Dave was the more stoic of the pair; Carroll was a bit more…demonstrative and while he could show a temper from time to time, it was also comforting to have Carroll as an ally. Once I made him mad. I can’t even recall what I said, but I was sitting in the park’s little Cushman cart that we used to patrol the campground and Carroll was standing next to it, giving me, for whatever reason, the business.

Keep in mind Carroll Clark was a big fellow who could snap me in two if he had a mind to. Whatever I said —it was probably some of my hippie enviro propaganda–it hit a nerve and he grabbed hold of the roof and starting rocking me and the cart back and forth, sideways, until I thought he was going to flip me over. Suddenly he seemed to realize he was about to roll me and a 700 pound golf cart into oncoming traffic and he stopped and grinned and said, “Darn…I’m a lot stronger than I thought.”

But on another occasion, his strength was my salvation. The previous evening, I’d put myself in a difficult, even stupid, predicament, when I tried to oust a couple of young, obnoxious, illegal campers from the park. I’d found them in Salt Valley, off road,and my righteous indignation got the better of me. I was out of radio contact, and when I confronted the two miscreants, they came unglued. One of them became physically threatening. When I stepped back and placed my thumb on my service revolver, the more volatile of the two screamed, “You take that gun out of your holster and I’ll shove it up your fucking ass!”

It occurred to me at that moment that he was probably right. If I did pull the weapon, I could never justify shooting the guy for illegal camping, and he might just take the revolver away from me and do as he suggested.

So I told them they had to leave and made a tactical retreat. A few minutes later, they loaded up and left, but not before stopping to tell me they planned to exact their revenge.

The next day, incredibly, these same two jerks showed up (legally this time) at the campground. It worried me. At lunch, as usual, Carroll, Dave and Rocky showed up and while they munched their meals, I told the Guys about my late night encounter, the proposed gun up my butt, their threats, and now, the fact that they were back.

Carroll especially bristled. “Those little shits came back? ” he asked. “Where are they? What campsite?”

“Site 28,” I told him. “And I wish they’d just leave.”

Later that afternoon, it was time for me to make my tedious evening rounds to collect camping fees. Of course, my would-be gun depositors had made this particular day more interesting and I walked toward site 28 with great trepidation.

But as I approached them from the road, they were at the picnic table looking as nervous as I was. When they saw me, the boys leaped from their seats, as if to welcome my arrival, and were downright effusive with accommodating smiles and deferential remarks. They even invited me for dinner.

And more than anything else, they kept apologizing for their boorish behavior of the night before. Over and over. I was relieved that they felt so contrite, but their pandering started to annoy me. I felt like saying, ‘Okay fellas. Enough is enough.’ Finally, it was time to go. As I packed up my clipboard and their eagerly paid three bucks, one of them asked meekly, “Could we ask one favor of you?”

“I guess,” I said. “What is it?”

“Well, could you tell your friend that we apologized to you and that we really meant it? Could you do that?” They looked scared.

“I’m sorry,” I replied, “but I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Your friend…The big guy. His name tag said ‘C. Clark?’ Uh…Mister Clark?” He, Mr. Clark came by here a while ago and, well, we thought he was going to kill us. He grabbed us both by the back of our necks and kept smacking our heads together. I think he might have..well…lifted us off the ground by our necks. He kept yelling, ‘If you ever try to hurt my little buddy Jimmy again, you’ll wish you were never born!”

Then the kid looked at me and asked, “So is your name Jimmy?”

Good grief I thought. Well, Carroll does call me Jimmy, just to aggravate me sometimes. And I did mention the campsite number. It’s good to have strong friends who can smash heads together.

I turned and said, “Yeah…I guess I’ll tell him. He’s going to be back real early tomorrow. I strongly advise you not to be here. He doesn’t forgive easily and he never forgets.”

They nodded, eyes bulging. I think they left before dawn. Later, I told Carroll about the incident. He smiled and said, “How come you get to carry a badge and I don’t? I’ll clean up this park in an afternoon.”

He winked at me and climbed into the park power wagon.

“Thanks, Carroll,” I said.

“Any time, Jimmy.”

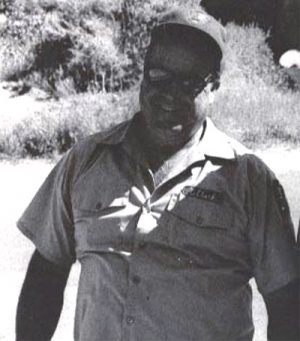

ROCKY NEWELL…

And finally, there was the Rocket Man. His name was Rocky Newell and he once told me he’d been a prize fighter. He had the mug of a guy who’d taken a few punches but had thrown even more. And, like his compadres, he didn’t have a lot of time for bullshit. He was born in Lester, Colorado, out on the edge of Great Plains south of Walsenberg, but had grown up in Rockvale, near Canon City. He was a sailor during WWII and often regaled us with war stories, though I’ll be damned if I can remember them.

Rocky was one of the greatest conservationists in the history of the movement, though he gets very little credit for his efforts. Rocky practically created his own industry within the confines of his seasonal maintenance job.

Rocky Newell was a man who hated to see anything go to waste. Anything. He was the original recycler. And he was always on the lookout for objects that could be reconditioned and used again. His favorite target was aluminum, of course, but he cast a wide net.

Rocky kept more good stuff from going to the dump than perhaps any man alive. I doubt if a single empty aluminum can ever left Arches National Park if it didn’t leave with Rocky. In those days the NPS had no official recycling plan, so Rocky took it upon himself to provide the service. I put out a spare garbage can and hung an “aluminum cans only” sign on it to help out, but it was mostly Rocky’s relentless pursuit of aluminum that allowed him to supplement his income by a few bucks each week (he’d never give me exact figures on his aluminum booty).

The problem was, most people didn’t care or notice our recycling can; they’d just hurl their empties into the big bins, after which they wound up in the big garbage truck. But that wouldn’t hinder Rocky. I’d come back to the trailer at noon for lunch and as I passed the NPS garbage truck, I often detected a slight movement coming from its innards.

“Rocky!” I’d yell, “Are you in there?”

“You bet Jim-O,” he’d answer.

“Any luck?”

“A few cans and a cook stove,” he’d advise.

But he pursued more than just aluminum. Anything that could be recycled, Rocky claimed: discarded tents, sleeping bags, cook stoves, articles of clothing—even food. Nothing went to waste.

He once dropped by with a bag full of fruits and vegetables and, honestly, they looked a little ripe. But Rocky assured me the produce was fine and suggested I make a big salad for dinner.

That evening, still dubious about his offering, I decided to pass on the salad idea. Not thinking clearly, I threw it…in the garbage. The next day at noon, there was Rocky, holding the salad that wouldn’t die.

“What’s wrong with you?” he growled. “This is good food. Don’t waste it.”

I nodded meekly and promised I’d never make the same mistake. That night I drove out to Salt Valley and left the fruits and veggies in the desert—out of sight from the road. You couldn’t be too careful.

One of the saddest days of his life came when Moab City closed the dump to junk salvagers like Rocky. “If I can’t make an extra $2500 a year from dump junk,” he used to say, “it’s a bad year.” He found everything from vacuum cleaners to curling irons up there, brought them home, fixed them and then had a yard sale.

Rocky finally retired from his park job and became the crossing guard at Helen M. Knight. He was known for the glares he shot at those who failed to heed his warnings. If Dave Baker possessed “The Scowl,” Rocky Newell’s was surely the “Glare of Death.” It was not wise to cross the crossing guard.

* * *

When I left the Park Service all three of the Three Amigos were still working at Arches, but all of them retired soon after. Rocky and Carroll left in the late 80s. Dave gave it up in 1990 and devoted his time to his family and friends, his daily walks, and to, of course, what many of us called the most magnificent vegetable garden in southeast Utah. It was his pride and joy. Dave passed away in 2018 at the age of 93.

Likewise, Carroll spent his remaining years in Moab. He tried to keep the orchards going, but the work was overwhelming and the price of land–and taxes–made it impossible for him to hold on. Moab was changing faster than anyone could imagine. Carroll died in 2014. He was 79.

Rocky Newell left us first, in July 1999. He’d stayed active and involved after his retirement, and always had a good word to say. In his later years, he turned to art –— gourd art to be exact. His creations were beautiful and I regret that he never tempted me into buying one (which he proudly displayed and sold out of the trunk of his car).

I saw Rocky the day before he died, standing at the post office in those big baggy shorts he was so fond of wearing. He gave me a wave and his standard, “Jim-O!” greeting. As it happens so often to all of us, I had no idea that was the last time

I think about Dave and Carroll and Rocky a lot these days. And the men and women who were cast from that same mold. Tough but compassionate, honest but full of humor and irreverence. We’ll never see their likes again. It was the end of an era.

Next time: Lions and bobcats and ravens and bears…Oh my!

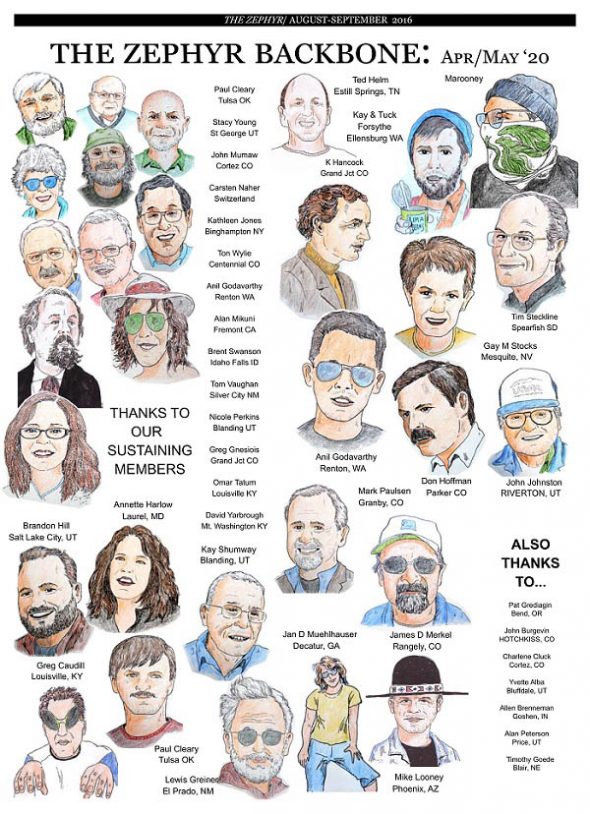

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Click Here to read the previous installments of Ranger Stiles’ Wildlife Observation Notes…

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Thanks for writing the article, I really enjoyed reading about my Dad and his co-workets he talked so much about, including you.

Thanks for writing the article Jim. I used to stop by and visit with Dave on his porch or in the living room and enjoyed his stories so much. I got to do some roofing there for him also. He was a fine person.

My aunt recently forwarded to me the article where you remembered a few Moabites who we rangers at Arches NP. Rocky Newell is my grandfather on my mom’s side.

I wanted to let you know that it really brought back to me what he was all about – he was a no-BS kind of guy. I have fond and long-lasting memories of him even though I was only 9 when he passed.

I remember him taking me on “hikes” to go collect golf balls on the holes where errant shots were not chased by the players. The gourd-art was fantastic – so many pink flamingos! I believe we still have many in my mom’s basement. Not only his “Glare of Death”, but he had the definition of a “holler”, that gravelly voice.

Thanks again,Charlie