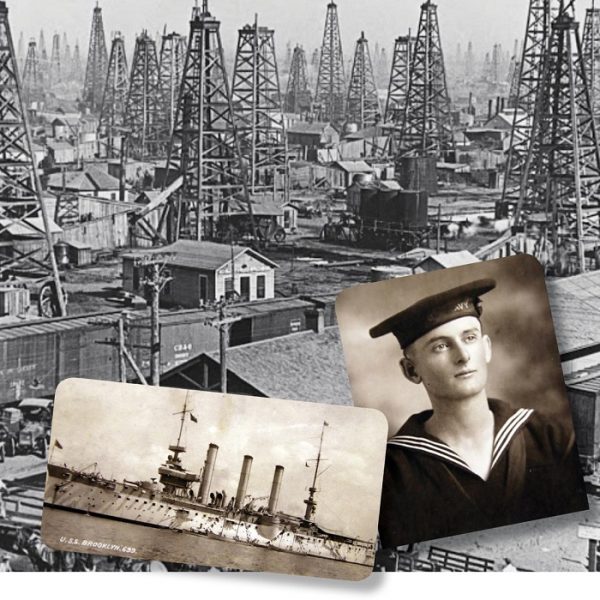

My grandfather, Hayden, was a soft-spoken Baptist who grew up in south Texas during a period when converts were taken to a muddy creek and, well, dunked “in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Amen.”

He practically froze his keister off aboard an armored cruiser on station off Japan, China and Russia as part of U.S. strategy to contain the Bolshevik Revolution after World War I.

Hayden worked at whatever jobs came along, including leading a surly mule team delivering ice to sweltering rich folks in Houston. He was affectionately known as “Peachy” because of his lifelong sweet tooth for fruit of the family orchard.

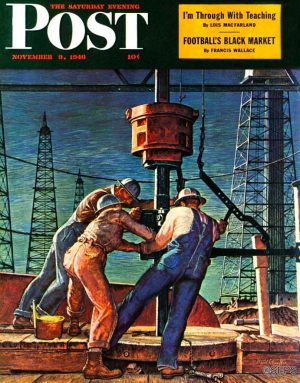

Once upon a time, we harbored a soft spot for his kind as a class that built the juggernaut called “America.” Art and popular media of the day reflected and amplified that respect.

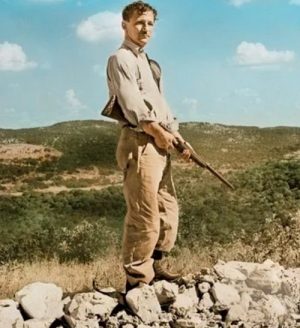

I still enjoy those stories. One of the taller tales was about the life and times of Gene McCarthy.

“Remember the time he made a half-million from a field that all the oil companies said was dry? That’s nothing, once he was a million and a half in debt, so he built a $700,000 house just for the hell of it. And remember the Shamrock opening in ’49, broadcast nationally on radio, when everybody who was any body was there? And the time the Hous ton Country Club wrote him a letter saying that, all in all, they’d rather not have him around the place?”

McCarthy was a larger-than-life role model for many of us baby Baby Boomers.

James Dean portrayed McCarthy in the 1956 movie “Giant,” a retelling of Edna Ferber’s novel. McCarthy was a rascal and buccaneer, even sporting a pencil moustache in the style of Errol Flynn and Clark Gable. He was the latest in a long line of Euro-Texicans stomping around, pursuing their pleasure, taking risks and considerable bounty back to Houston and Dallas. They didn’t look back at the havoc they wrought.

Taking cues from McCarthy and other legends of the Oil Patch, me and my high school buddies became part of the vanguard in the latest wave of a continual cultural transformation that defines the Way of the West: from indigenous peoples counting coup versus indigenous peoples counting coup versus National Park “visionaries” (America’s Best Idea) confiscating their ancient hunting grounds and sodbusters and their mounted protectors sporting Winchesters and snappy Stetsons versus cattle barons versus sheep herders versus drillers, diggers and loggers versus, nowadays, part-time residents of faux adobe, vaguely exotic but modern-y villas who feel entitled to a $100 meal (with a delicate French red, if you please) and Navajoland sunset views served up by someone somewhat indigenous making $10 per hour and living in a trailer 30 miles away.

I’ve been there.

Skiing and hiking in the sacred (for Taos Pueblo) Sangre de Christo mountains of northern New Mexico? Check. More skiing, adjacent to the sacred (for Mescalero Apaches) Sierra Blanca and playing the quarter horses at Ruidoso Downs a few miles away and the slots. Check. Fine art, including Navajo jewelry, paintings, weavings and pottery, in Santa Fe? And even more skiing. Check.

That’s why the Chuck-A-Rama sociologist in me believes appropriation of the Navajo Way by even marginally affluent Americans, Navajo political opportunists rendered untouchable by invoking “sovereignty,” and denigration of working-class culture masked by NIMBYistic environmentalism lie at the core of the rift transforming San Juan County and many other parts of the West. Racism? Yeah, that’s always the default isn’t it? (NIMBY means “not in my backyard.”)

Take the Bluff Arts Festival. A three-day event held in October, the fest has no antecedent. It didn’t evolve organically over a period of years as an expression of pride in the accomplishments of, say, Mormon pioneers, Navajo Way or Cowboy Culture.

It reflects a transplanted aesthetic sensibility, at least in part, because many of its current residents are themselves transplants.

Take “Dark Skies.” The nine-minute Vimeo preceded a panel discussion about “the importance of keeping our skies dark” at what was billed the “Bluff Film Festival” embedded into the arts fest. It was directed and edited by Salt Lake City-based public radio personality Doug Fabrizio and made possible through generous donations from listeners and viewers like you. Thank you.

Here’s the promotional blurb:

“There’s a price we pay when we illuminate our cities. The light interferes with our sleep cycles and can have real and serious health consequences. There are a few remote places, though, where you can still find true darkness. One of those is Torrey, Utah, where amateur astrophotographer Mark Bailey has an observatory that he calls his ‘portal to the deeper cosmos.’ ”

“Light pollution” is a thang to some folks in environmentally woke enclaves such as Bluff, Kanab and Bailey’s Torrey and operators of tourist destinations who see opportunities in so-called astro-tourism. Others, less woke, mundanely see street lights as a source of personal security.

Grandpa Peachy was entering middle age, much of his life until then illuminated by lanterns whose wicks were dipped in oil and candles made of petroleum wax, when the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 turned darkness to dawn for many rural Americans. I wonder what Peachy would think about people who nowadays want to turn out the lights?

Roll on, Columbia, roll on

Roll on, Columbia, roll on

Your power is turning our darkness to dawn

So roll on, Columbia, roll on

–Woody Guthrie

Thousands living on the Navajo reservation, a few miles from the film’s screening, might prefer to not remain in the dark. “Among the 55,000 homes located on the 27,000 square mile reservation, about 15,000 do not have electricity,” according to Light Up Navajo. “They make up 75 percent of all unelectrified households in the United States.”

New Bluff contrasts with old New Helper, a once-thriving railroad and (dirty) coal town 200 miles to the north that had Grandpa Peachy visited he might’ve briefly been transported to the days when you had to work for a living, walk 10 miles to school and scrape ice off the outhouse seat before taking advantage of its accommodation. New Helper embraces its past as part of a modest economic comeback. Although thin, it has at least a ring of authenticity.

On a similar but grander and more sanitized level, the ruins of Park City’s (toxic and hard-scrabble) glory days are part of a niche appeal so strong that walk-up-to-the-window, same-day-lift-ticket buyers willingly pay $189 to glide through time for one day.

The most economically significant activity in southeast Utah of the past 100 years, oil and gas exploration and extraction, is MIA at the Bluff fest.

***

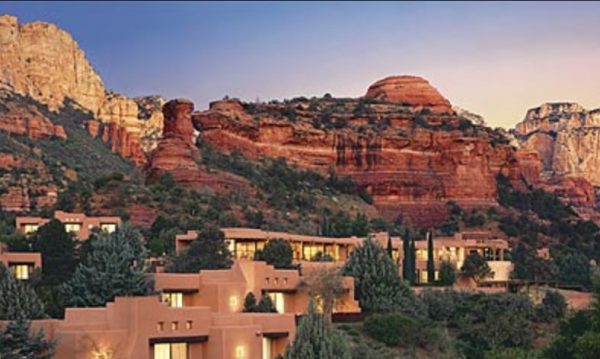

THE COMPLETION AND FORMAL OPENING of Bluff Dwellings Resort and Spa is another example of cultural deep-sixing. It marks a departure from the leafy genuineness of Recapture Lodge and roadside funk of Cottonwood Steakhouse (I’d rate the steaks, service and atmosphere there four stars) just down the road, or anything else in San Juan County for that matter. The town is now bookended by “high-end” motels, the log-lodge-style Deseret Rose anchoring the west end.

And smack dab in the middle is an 8.5-acre parcel listed for $400,000, making it one of the most expensive pieces of prime undeveloped commercial real estate in the county. Somebody’s pricing that patch of sand and noxious weeds as if Bluff were baby Sedona, Arizona. Could it become the town’s commercial center? When (or if) the property sells at its current asking price, the pastoral nature of Bluff will be irretrievably altered.

In a news release, Jared Berrett, Bluff Dwellings CEO, says the resort is about “being true to the landscape, the indigenous people, and the surrounding wilderness. Designing, building, and operating the 13-acre cliff-bound property is a true labor of love. We want to share our passion with visitors so they experience nature in a unique way with uncompromising amenities and guest experiences.”

The $6 million enterprise is unlikely to mitigate much of the grinding poverty on the nearby Navajo Nation. The “hospitality” industry generally does not pay much more than poverty wages; employment typically is seasonal.

Bluff Dwellings’ grand opening coincided with increasing public awareness in the United States of the global spread of novel coronavirus, clouding its future. By March 3, the virus had infected more than 90,000 around the globe and killed about 3,000; a real-time tracker reported 83,436 people in the United States had the disease by March 26. The death toll was 1,217 and skyrocketing.

The Navajo Nation, home to a significant percentage of the Bluff workforce, confirmed 69 cases by the end of March. Both Bluff Dwellings and Deseret Rose resorts had closed. The town’s other motels also closed, as did the restaurants.

Cruising through Bluff was eerie, like stepping back in time to pre-tourist Bluff, a farming and ranching oasis in the desert of the West. I half expected to see John Wayne and his cavalry troopers come riding through town from Monument Valley.

Public health officials in San Juan County and counties immediately to the north told residents that visitors pose a health risk. San Juan County Public Health said, “We ask all visitors, potential visitors, and county residents to please stay home. Avoid all unnecessary travel, right now. Avoid all leisure traveling, right now.” Southeast Utah Public Health, which covers Carbon, Emery and Grand (Moab) counties, was more aggressive. The agency closed motels to non-residents of the county on March 16.

The director of the Bluff-based pro-Bears Ears National Monument activist group Friends of Cedar Mesa, Josh Ewing, also advised visitors to stay away.

“Our field team has never seen more campers along Comb Ridge and local BLM campgrounds are packed. This has led people to camp in previously undisturbed campsites and impact sensitive areas with archaeological resources. …

“Even prior to this outbreak, Friends of Cedar Mesa noted a growing problem of human excrement in Bears Ears. Due to COVID-19, nearby services at community gas stations and restaurants are limited with many restroom facilities closed — creating even more of a potential problem.”

Turns out, closures around Moab pushed campers seeking greater “social distance” from possible human carriers of the virus south into Bears Ears country, which nowadays is a relatively familiar destination thanks in part to Friend’s participation in a multi-year, multimillion-dollar national campaign to “protect” the Cedar Mesa region of southeast Utah. Much of Friends’ funding comes from the industry that outfits those campers.

Ewing’s counsel reflected the consensus of like-minded environmentalists, who personally embrace recreation on public lands and professionally acknowledge its inevitability while attempting to mitigate the havoc:

- Neighboring counties ask Yellowstone National Park to close

- Rocky Mountain National Park closes amid coronavirus outbreak at the request of mayor, local health department

- National parks are free, but some oppose that amid the virus

- Rangers at risk as parks remain open in pandemic, advocates say

- Latest coronavirus casualty: public restrooms on national forests

- Outdoor meccas are not a social distancing hack

The headline above Ewing’s Tribune op-ed was, “Now is not a good time to visit Bears Ears.” Several San Juan County residents responded with a bit of snark: “There is never a good time to visit Bears Ears.”

In a comment posted on the Canyon Country Zephyr’s Facebook page, Jim Stiles, founder of the Zephyr, reflected the sentiment.

“I have to wonder. Had Bears Ears National Monument NOT been created, had efforts been made to protect its antiquities via existing laws like the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA), had the area NOT been endlessly promoted by the recreation industry and the mainstream environmental community, including Friends of Cedar Mesa (which is primarily funded by the recreation industry), would Cedar Mesa be the crowded mass of tourists and recreationists that it is right now?…

“Isn’t it finally time that the recreation industry and Utah environmentalists, including well-funded groups like FCM, did a little soul-searching of their own?”

Even a global pandemic has not kept people away from a fragile and sacred landscape and crapping on it. To borrow a line from Pete Seeger about something completely different, “We’re waist deep in the Big Muddy and the big fool says to push on.”

***

A bit of crystal-ball gazing

***

LOST AMID THE OPENING of the resort and spa and concerns related to the global pandemic was news that Denver-based EOG Resources, Inc. had notified the Bureau of Land Management it would pull its plans to drill two oil and gas wells a few miles north of Bluff.

“On February 28, 2020, EOG Resources, Inc. advised the BLM that the company no longer intended to pursue two applications for permit to drill (APDs) submitted in 2016 (Recapture 4-34H and Recapture 11-22H),” said Amber Johnson, acting Monticello Field Manager, in an email. “We consider the APDs withdrawn effective from the date of notification. The BLM will not issue a final decision on the environmental assessment for the APDs, as there is no longer an action to consider.”

EOG’s decision came after the Bluff Town Council sent a letter to the BLM in early February opposing the wells. It cited concerns related to possible contamination of its water supply, echoing about 40 comments sent to the agency in 2016 as the application process began to unfold.

“I’ve struggled and struggled and struggled with the conflict between oil and gas money coming into the community,” said Leppanen, who was quoted in a KUER report. “But if we don’t have water, we don’t have anything.”

Leppanen, who became Bluff’s first mayor in 2018 after winning election by three votes as a write-in candidate, has a track record of attempts to block energy-producing projects, including a solar farm on land owned by Utah’s School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration, or SITLA, along the highway leading into town.

“If we’re going to have a solar facility here, then it needs to be the right size and in the right place,” said Bluff Councilman Brant Murray, who was quoted in a KUER story last year.

“I’m a little less inclined than Brant,” said Leppanen. “I’m saying really strongly: I don’t want it here. I want it to go somewhere else.”

KUER reported that David Ure, director of SITLA, said the project would generate renewable energy for up to 30 years. For Bluff, with an estimated budget of about $70,000, it would mean revenue of up to $300,000 a year and jobs. For SITLA, the project could bring up to $600,000 annually. The agency sells state land to help fund Utah schools.

“This solar field will bring an awful lot in to them,” he said. “I’m guessing it will be around $500,000 or $600,000 for us.”

Fears of some Bluff residents are reflected in their uncompromising opposition to anything and everything connected to energy development and suspicions of BLM.

Leppanen and others opposed an oil and gas lease sale in southeast Utah last year, suggesting the landscape could be overrun with drilling rigs, new roads and pipelines, turning the area into a “single-use landscape.”

I wonder if they read BLM’s environmental assessment, or “EA” in the acronym-plagued world of the federal government. They would’ve discovered their concerns were addressed – at least considered – within the 143 pages of a policy analysis required by laws enacted over the past 40 years or so and regulations and policies put in place to administer those laws.

(Editor: Mayor Leppanen did not respond to an email request for comment.)

Angst-driven hyperbole of Leppanen and others notwithstanding, it’s much ado over not much. We’re only talking about four wells. “For the analysis of the 19 nominated parcels encompassing 32,067.42 acres, the MtFO (Monticello Field Office) estimated maximum of four wells would be drilled. … Over the last three years, six wells have been drilled in San Juan County. Out of those six wells, only one well was capable of production. Statistically, it is more probable that three wells would be drilled for the nominated parcels (EA page 20).”

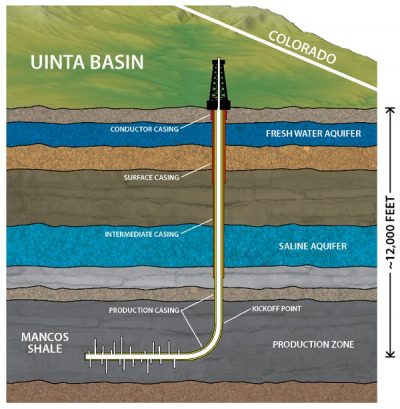

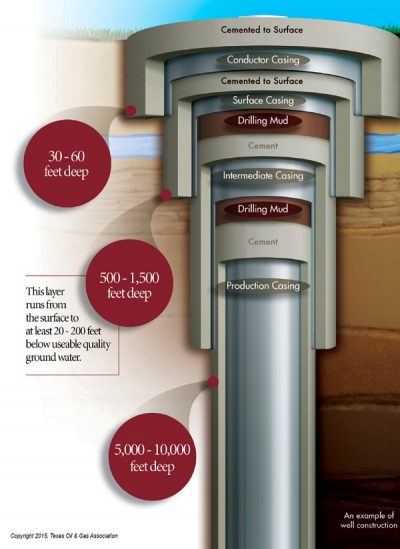

EOG’s recent decision to forgo drilling north of Bluff leaves questions unanswered. Bluff’s Town Council asked whether BLM had fully analyzed risks associated with the wells, which would’ve used hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” to extract oil and gas. Environmental groups have been critical of the process for several reasons. One is the fact that it involves cracking rock formations deep underground by injecting water (often a lot of foul water), toxic chemicals and sand at high pressure. The technical term is “induced seismicity.”

“The fact that underground fluid injection can trigger damaging earthquakes has been understood since the 1960s, but historically such earthquakes have been very rare,” according to studies cited by the American Geosciences Institute. ” The sharp rise in noticeable earthquakes in the central United States from 2008 to 2015 was caused by massive increases in the underground disposal of produced water from the oil and gas industry. Since mid-2015, declining rates of produced water disposal have led to fewer earthquakes in the central United States.”

There are probably around 800 oil and gas operations in Utah using hydraulic fracturing. I haven’t been able to find evidence the process has had any impact on water supplies – at least groundwater thousands of feet above oil and gas targets.

Water wells in Pavillion, Wyoming, might’ve been contaminated with fracking waste stored in unlined pits dug into the ground. It’s a serious issue. Critics of EOG’s proposal, however, did not mention possible problems created by seepage from foul surface water.

In the environmental assessment dated December 2019, hydrologist Ann Marie Aubrey determined that “with the required SOPs (standard operating procedures) and COAs (conditions of approval to drill), surface water and groundwater resources will not be impacted to the degree that would require detailed analysis in the EA.”

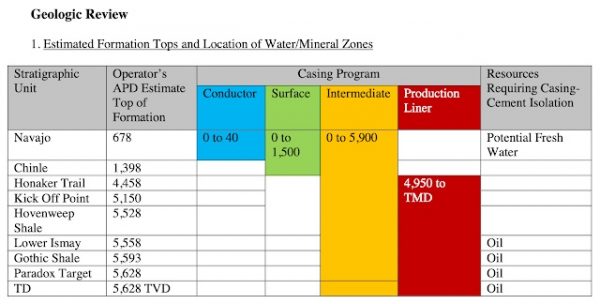

Although BLM declined to comment on how Aubrey arrived at her conclusions, they could’ve been derived, at least in part, from the requirement to isolate well fluid from the aquifer using casings (see graphic to the Left); the vertical distance (thousands of feet) between the source of well water, the Navajo Aquifer, and any oil and gas; the porousness or permeability of rock between the wellhead and oil and gas deep underground; use of technologically sophisticated well-pressure monitoring to detect leaks and force operations to shut down; and the fact that it takes thousands of years for the aquifer’s water in the general vicinity of the proposed oil and gas wells to reach sources of water wells in the town of Bluff, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study.

Possible consequences of fracking has led to extensive research into the mechanisms, likelihood, and prevention of groundwater contamination:

“Studies of thousands of hydraulic fracturing operations in the Barnett Shale (Texas) and the Marcellus Shale (Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia) have found that hydraulic fracturing operations took place more than 3,000 feet below any aquifers, and that the fractures generated during these operations generally extended upwards for only a few hundred feet.

“A few fractures extended more than 1,000 feet, but in all cases, there were still thousands of feet between the maximum extent of the fractures and the freshwater aquifers. Hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas in most areas therefore does not appear to generate fractures that allow for the migration of hazardous chemicals into freshwater aquifers.”

***

WICHITA FALLS, TEXAS, the oil town in which I grew up, created Lake Arrowhead in the early 1960s. Civic-minded residents were concerned that their primary source of water at the time, Lake Wichita, was nearing the end of its useful life. It was beginning to silt up.

The site chosen for a new reservoir was above an oil field.

Unease then was similar to that expressed by residents of Bluff now: Is our water supply threatened? City and state officials and various and sundry experts weighed in. Eventually, land was purchased, wells were plugged, a dam backed up water in a slow-running creek, and the oil field began to fill up with water.

Although the situations aren’t exactly comparable, the common denominator is a healthy suspicion of the oil and gas industry. Little tar balls rolling onto Gulf Coast beaches for no apparent reason (It’s a natural process. Nothing to see here) and blue-skies-forever flimflam of official spokespersons irk Texans. So I asked Daniel Nix, utilities operations manager in Wichita Falls, the guy in charge of the water supply there, to weigh in.

Q: Over the past 60 years, has seepage from the plugged Arrowhead wells ever been a significant water quality issue?

We have only experienced one extremely small seepage from an old connector line 10 years ago. It was easily contained with booms and the leak repaired by a diver.

Q: What contingency plan does Wichita Falls have in case of a major leak?

We have multiple reservoirs to pull water from So if a leak occurred, we would isolate Lake Arrowhead and pull from other reservoirs while the repair was made.

I also talked at length with Dustin Doucet, senior petroleum engineer at the Utah Division of Oil, Gas, and Mining. He knew a little more about Utah stuff.

I asked him point blank: Given what we know about hydraulic fracturing, mitigation technology such as casing and the geology of the area, including permeability of rock layers thousands of feet below the aquifer and the fact that any fluid seeping from the oil wells would take literally thousands of years to reach Bluff water wells, should residents of Bluff have any concerns about possible contamination of their source of water from EOG oil and gas wells?

After considering the question for a moment or two, the engineer responded without exaggeration, embellishment or apocalyptic prose: “No.”

(Keshlear is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He never worked the oil rigs, but was a gandy dancer for a few summers. Laying ribbon rail for Burlington Northern along the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers helped defray costs of a degree in journalism at the University of Montana. And the fly-fishing was darn good.)

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Bluff may not be the new “baby Sedona” but it’s the new baby Moab for sure. I remember thinking it would never happen but thankfully it is happening before our very eyes.

Bluff Dwellings Resort and Spa indeed. I can barely wait for the Championship 18 hole scenic golf course and the time share condos to populate the golf course to arrive. That cheap $400,000 8 acres of useless sand and weeds in the middle of town would be the perfect spot for those condos and the big alfalfa field on the east side is the perfect spot for the golf course. Not to mention all of those minimum wage seasonal jobs that this will provide for those poor folks who live across the river. Hey, that means a new Dollar Store! The opportunities are endless for smart investors who want to bring the 21st century to Bluff.

Thanks to FCM, business minded progressive thinkers, and the new Bears Ears National Monument for bringing Bluff into the future it was meant to have.

Dammit, where’s that sarcasm font on my keyboard now when I really need it?