The fire was now burning brightly. We sat down around Grandfather as the firelight played over his face and white hair. We could hear the wind blowing outside, but everything was peaceful inside the hogan and we were all contented. Grandfather began the story he had promised to tell us, and we soon forgot everything else in the world, just listening to his voice and the low humming of the wind on the smoke hole in the top of the hogan.

—Wolfkiller

On a cold spring evening in the early 1860s, in the wild Utah/Arizona borderland country near Monument Valley, a Navajo elder gathered his grandchildren around the hogan fire and told them a folktale.

After the mythical first desert sparrow was created and learned to appreciate his new gray coat, a nighthawk, whose coat was black and white, looked at him jealously. “I do not think my coat is half as pretty as yours,” the nighthawk complained. Just then the two birds heard the whisper of the wind, which said to them, “It is bad to be too much dissatisfied, but if we are all content to just sit down and not try to better ourselves, it would be a sad world. There would be no breeze blowing, the sun would not move, and we should all die. So you see the Creator knew best when he made us, but he did not intend that we should be unpleasant or have an ugly disposition because we are dissatisfied. He has no patience with us when we try to make things unpleasant for others, and he punishes us for our actions. We should make the best of our circumstances when we cannot change them, but there is usually a way to change the things we do not like if we try.” Through the wind’s quiet voice, Mr. Desert Sparrow and Mr. Nighthawk came to understand that they could appreciate what they had while still having ambition, and they could treat others with kindness even while striving to better themselves.

The grandfather’s deeper message to the children was that they could gain insights and wisdom when struggling with the tough questions of life by being receptive to what he called the whisper of the wind. One of the boys took particular grasp of his grandfather’s teaching, applied the principles to his life, and grew up to become a most honorable man. When my great grandmother, Louisa Wade Wetherill, met him in 1906, she was immediately impressed by his kindness, integrity, and depth of character. “He was very quiet and always smiled. He never participated in the arguments that sometimes came up among the other workers, but just went about his own business, paying no attention to what might irritate the others. With his earnings, he bought clothing and food for his family, while some of the other men gambled most of their money away. They called him Wolfkiller.” Over a period of many years, Wolfkiller recounted his grandfather’s remarkable lessons to Mrs. Wetherill, and she translated and recorded his story for the benefit of future generations.

When Mrs. Wetherill finished writing the narrative in 1932, she sent it to a prospective publisher. He expressed interest in it but had difficulty believing that it was all true. “You say that Wolfkiller discussed the injustice of life with his brother,” he wrote. “I doubt very much whether a child of six would talk or know of such problems. It would be better to make the boy about twelve or fourteen.” He later rejected the story, saying that it was just folklore and would not sell. For seventy-five years, the manuscript languished in the family archives until finally receiving the recognition it deserved. In 2007 it was published as Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth-Century Navajo Shepherd.

The skepticism about Wolfkiller’s message was symptomatic of a deeper antagonism toward the traditional Native American approach to life that was well-engrained by the early 1900s and is even more prevalent today. The old way of thinking is unscientific, illogical, and anti-progress, they say. Humans have evolved into something better, and primitive people are just relics of the past, unable to embrace the new and superior ways of modern society. For more on this, see my article in the October/November 2013 Canyon Country Zephyr, “The Myth of Progress”.

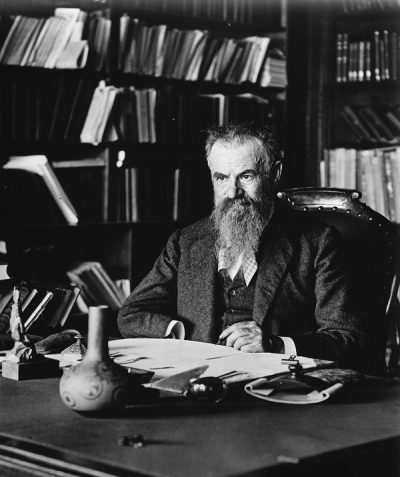

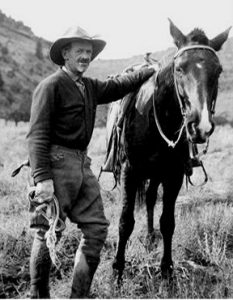

One of the most verbose proponents of the theory of social evolution was the Colorado River runner, John Wesley Powell, who, in his later years, devoted much of his time expounding on what he called his “Philosophy of Science”. His most notable publication was his book, Truth and Error or the Science of Intellection. He began that discourse with a criticism of an Indian man named Chuar who he met at the north rim of the Grand Canyon. “Now Chuar believed that he could throw a stone much farther along the level of the plateau than over the canyon, …and he explained to me with great care that the hollow or empty space pulled the stone down,” Powell recounted. Truth and Error was Powell’s attempt to correct such foolishness and lay out what he believed was the only right method of reaching certitude, i.e., the scientific method.

In Powell’s mind, the whisper of the wind could not have been a legitimate source of insight. He argued that the intellect is the one faculty through which truth is discerned, and belief based on any other method is delusion. “In the intoxication of illusion facts seem cold and colorless, and the wrapt dreamer imagines that he dwells in a realm above science—in a world which as he thinks absorbs truth as the ocean the shower, and transforms it into a flood of philosophy. Feverish dreams are supposed to be glimpses of the unknown and unknowable, and the highest and dearest aspiration is to be absorbed in this sea of speculation. Nothing is worthy of contemplation but the mysterious.” Powell further elaborated on this theory in a journal article: “Many, strange, foolish, and false are the stories that Nature tells to the untutored savage. Nature teaches men to believe in wizards and ghosts; Nature fills the human mind with foolish superstitions and horrible beliefs. The opinions of the natural man fill him with many fears, give him many pains, and cause him to commit many crimes.” He argued that modern, enlightened people have escaped this mental morass. “This power to reach inductive conclusions in opposition to current and constant sensuous perceptions is the greatest acquisition of civilized culture,” he proclaimed.

Powell was a disciple of social theorist Lewis Henry Morgan whose book, Ancient Society, or Researches in the Lines of Human Progress from Savagery Through Barbarism to Civilization, was first published in 1877.Morgan wrote that human culture evolves and progresses through those three stages. He purported to document the “Growth of intelligence through inventions and discoveries,” thus inferring that non-technological societies, such as traditional Native Americans, are intellectually inferior. Powell adopted Morgan’s theory and elaborated on it in two articles: “From Savagery to Barbarism” and “From Barbarism to Civilization”. He maintained that civilized society is not only intellectually superior, but morally superior as well: “In savagery, the beasts are gods; in barbarism, the gods are men; in civilization, men are as gods, knowing good from evil.”

“In savagery, the powers of nature are feared as evil demons; in barbarism, the powers of nature are worshiped as gods; in civilization, the powers of nature are apprenticed servants,” Powell wrote. He provided no evidence that he thought of nature as an intrinsic source of goodness and inspiration, but only as a force to be conquered. “Human evolution has none of the characteristics of animal evolution…. It is not by adaptation to environment, but by the creation of an artificial environment.” In this declaration, Powell accurately foretold the destiny of future generations, which are increasingly antagonistic toward nature and infatuated with artificiality.

Powell took the position that inventions are the source of goodness and inspiration: “The greatest intellectual achievement of civilization was the discovery of the physical explanation of the powers and wonders of the universe, and the intellectual superiority of man, by which he becomes the master of those powers and the worker of wonders.” Thus, he accurately foretold the proliferation of technology, manufacturing, and accumulation of manmade objects. “And all these inventions are made not because men struggle with nature for existence, but because men endeavor to secure happiness, to improve their condition; it is a conscious and intelligent effort for improvement. Human progress is by human endeavor.”

Upon further reflection, it can be seen that Powell, like his successors, had his own “foolish superstitions and horrible beliefs” that he might have felt compelled to correct had he been receptive to the whisper of the wind. He was a poor predictor of the future and had no grasp on the unintended consequences of the social changes he advocated. This is an indictment not just of Powell, but also of the many adherents to his ideology that have followed him.

The belief that reason is the only legitimate method for distinguishing truth from error does not meet its own criterion, i.e., this premise cannot be proven by reason and thus is inconsistent with itself. As such, it should be categorized as an unintelligible opinion rather than a verified truth. Philosophers call this a “self-referentially incoherent” proposition because, if applied to itself, it refutes itself. Contrary to Powell’s claim that he only accepted inductive conclusions, this is just one example of his practice of rationalization rather than rationality.

Belief in Powell’s version of progress is more characteristic of religion than of science. Although lacking a deity, his belief system entails some of the attributes of traditional religion: faith, which translates as confidence in human ingenuity and initiative to create a perceived utopia, hope, i.e., anticipation of a better tomorrow, and charity, which is interested in helping others create artificial environments.

In a very unscientific and naïve manner, Powell expressed his own faith-based beliefs that, using his own terminology, could be called “savage superstitions”. Not only are they unproven by the scientific method, they also can be seen to be false by the light of history:

- “…I have faith in my fellow-man, towering faith in human endeavor, boundless faith in the genius for invention among mankind, and illimitable faith in the love of justice that forever wells up in the human heart.”

- “Human providence is more potent than flood, more potent than drought, more potent than wind. The man of intellect wields a power that giants cannot exercise.”

- “It is thus that men are gradually becoming organized into one vast body-politic, every one striving to serve his fellow man and all working for the common welfare.”

- “…every man is dependent upon his fellow-man; he is therefore interested in the welfare of his fellow-man…. And as a man forever desires the good of his neighbor for his own sake, from generation to generation the desire for his neighbor’s welfare for his own sake gradually becomes the desire for his neighbor’s welfare for his neighbor’s sake. This it is that selfishness is transformed into love, and justice and love are developed into the ethics of mankind.”

- “Every man in all the years of his labor toils for his fellow-man and the practice is universal among all honest civilized men, and lasts from generation to generation; and universal practice is gradually becoming crystallized into universal habit. One man is trying to make better shoes for his neighbors, another man is trying to make better laws for his neighbors, and another man is trying to make better books for his neighbors. Every man is thus forever dwelling upon the welfare of his neighbors and making his best endeavor for his good, and thus the habit grows from generation to generation, until at last some men even forget that there is reward for service, and labor for their fellow-men because they love their fellow-men…. Man toils for the reward which must be tendered by his neighbor; but, more than all and higher than all, man toils for others without hope of reward from them, but receiving the bounteous reward of an approving conscience.”

The utopia Powell envisioned and the happiness and morality he predicted have not come to fruition, but, to the contrary, his approach has resulted in significant emotional dysfunction, societal turmoil, and damage to the natural environment. The so-called “progress” he promoted increasingly distances people from nature, and its promise of gratification and enlightenment through artificiality has resulted in mental distress, wars, holocausts, self-centeredness, and a dearth of wisdom.

Inventions did not turn out to be the panacea that Powell envisioned. “In our cities there is no more day and night or heat or cold,” wrote Jacques Ellul in his masterful 1954 book The Technological Society. “But there is overpopulation, thralldom to press and television, total absence of purpose.” Not only did technology fail to usher in an era of great happiness, but it has become the source of considerable meanness, deception, angst, depression, and dissatisfaction. No worry, though, because clever inventors have overcome the failure of their structures, machines, and gadgets to create lasting happiness by inventing chemical substances such as tranquilizers and even stronger drugs that might be able to do the trick

The modern soul is not satisfied with the acquisition of a reasonable quantity of money and manufactured things, but keeps craving more and more. How does the scientific method explain the insatiable lust of millionaires and billionaires for ever more wealth and their perceived need for extravagant and palatial mansions? The whisper of the wind would warn against these obsessions.

Inventions that are meant to solve one problem inevitably create many new ones. For example, creation of the automobile has resulted in massive extraction of natural resources, pollution, and accidents, and has necessitated vast infrastructures of mines, factories, roads, energy supplies, financial institutions, repair facilities, spare parts suppliers, packaging, and landfills. The inventions that deal with each of these challenges cause their own new problems, ad infinitum. The authors of the book, Affluenza, have delved further into the ramifications of the current sad state of affairs.

The expectation that humans will eventually become smart enough to create perfect inventions, that additional artificiality will solve the problems that artificiality has caused, or that a leader will arise who can guide society out of danger and into a utopia are fantasies for which the scientific method provides no credence and the whisper of the wind would reveal as foolishness.

The clamor, complexities, and distractions of the modern world drown out the whisper of the wind, and there are many whose ability to recognize its subtle guidance is so impaired that they would not hear it even if they tried. Those who do have the ability and inclination to hear it may be blessed to gain precious insights such as these:

- You have much to be grateful for.

- Perform acts of kindness.

- Look for the good in people.

- Just because it feels good does not mean you should do it.

- The means don’t justify the ends if the means are evil.

- Get close to nature, and you will gain great rewards.

- Integrity is its own reward.

- Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Very fine and wise article. Enjoyed it very much. Thanks

This excellent article is a prime example of the content that gives the Zephyr a unique voice in the canyon country as a publication dedicated to preservation of what existed before the crush of modern times. Akin to the efforts of environmental NGOs to preserve and protect the natural resources of the Colorado Plateau, the Zephyr preserves the history of the region’s cultures by curating the reports and stories of people living in a time of less disruption and better balance between man and nature.

Leake’s critique of Powell is important in understanding the destructive path of “progress”, particularly exemplified by the efforts of the Bureau of Reclamation to subdue and harness the rivers of the Plateau.

Unfortunately, the lessons that should be learned are ignored and the Plateau is still a target of exploitive schemes and developments.