Unless by the force of eloquence they mean the force of truth: for then I do indeed admit that I am eloquent. But in how different a way from theirs!

–From The Apology of Socrates by Plato

Every passion borders on the chaotic, but collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.

–From “Unpacking My Library” by Walter Benjamin

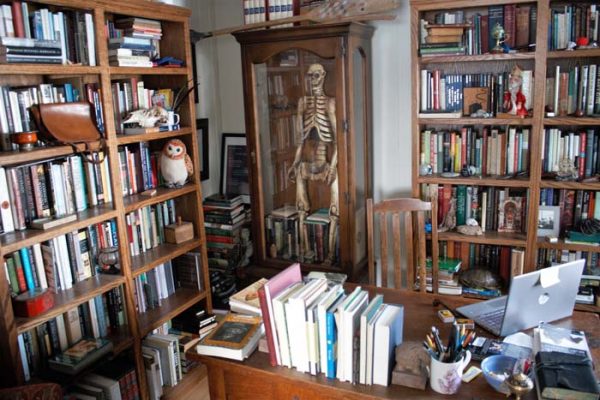

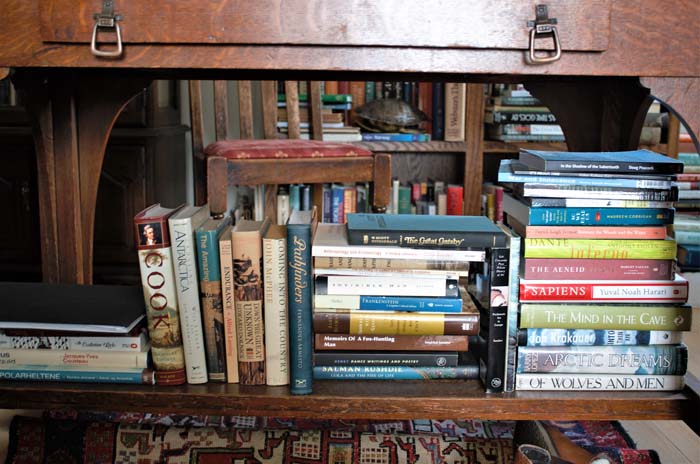

I have been shifting through and moving around piles of books. Here is a partial list: The Silk Roads: A New History of the World by Peter Frankopan, A History of American Tonalism: 1820-1920 Crucible of American Modernism by David A. Cleveland, The Selected Poems of Tu Fu, translated by David Hinton, The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame—which remains invariability if not at hand then somewhere close—Writings on Art by Mark Rothko, The Riviera Set 1920-1960: The Golden Years of Glamour and Excess by Mary S. Lovell, and The Angler’s Coast by Russell Chatham. There are piles of books in my home, including those piles of books in my modest library. There are piles because I have more books than there are shelves on which to put them. I read an essay recently about what it means to have more books than one will ever read. It means, the author implies, that the possessor of so many books is someone of insatiable curiosity and that the number of books suggest a willingness to fill-in the gaps of ignorance. As I often do when reading such extravagant claims, I think of the last line from The Sun Also Rises. “Isn’t it pretty to think so.”

Me…I’m just moving around books, managing the read and the unread.

I value the experience of reading, as it continues to be for many of us an experience of easy solitude. Throughout history reading wasn’t always an event of solitude or even silence for that matter. Reading aloud was a common practice in ancient times and the era of the early Church. In his book The History of Reading, Alberto Manguel reminds us of a moment in Augustine’s Confessions in which he, Augustine, notes the reading habits of Ambrose. The passage reads as follows:

When he reads, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still. Anyone could approach him freely and guests were not commonly announced, so that often, when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud.

His voice was silent and his tongue was still. For Augustine, this method of reading was at least uncommon. However, for most of us this is how we read. Our voices are silent and our tongues are still, while most of our minds, however, are detention centers for monkeys in the monkey brain universe.

I share some of these piles of books with my father. Many of the volumes were once his. Dad’s books comprise a collection of poetry, Shakespeare’s work in various editions, and commentaries about his plays. Dad has collected Classics in Greek and Latin and in translations. He has also collected books in a more esoteric vein, with titles such as: Etchings of a Whaling Cruise by J. Ross Browne, Four Historical Definitions of Architecture by Stephen Parcell, Elementary Arabic: A Grammar by Frederic Du Pre Thornton, Structure of The Visual Book by Keith A. Smith, and The Great Age of Fresco: Giotto to Pontormo published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. As Dad has told me many times, he grew up in a home without books, a home that essentially didn’t value art or music or reading. After he left home, Dad began to build a collection of books, of music, and of pieces of art when he could afford them. He collected, too, books about art, which were illustrated with the great paintings of the great painters. These were not academic books, but inexpensive coffee table books like Impressionist Painters by Guy Jennings and Renoir: A Master of Impressionism by Gerhard Gruitrooy.

Predictably, Dad gave books to me when I was growing up. I still have my copy of 50 Norman Rockwell Favorites, which I consider a companion piece for another Rockwell book I have called The Best of Norman Rockwell. This book was gifted to me by my dad’s dear friend, Lloyd Platt, and his family. The inscription reads “To Damon—Uncle Lloyd, Aunt Cheri, Michael & Michelle, March 31, 1983.” I was nearly 12 years old in 1983, and the book was a treasure to me. I wrote recently to Cheri, asking her about the book, and she wondered about the date. She told me it must have been “for one of my surgeries.” That’s probably true. I recall looking at the book in the hospital.

Another book I was given as a child was The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to The Magic Kingdoms by Christopher Finch. The book is listed at 60.00 USD circa 1983, which is the equivalent to 150.00 USD today, an astounding amount for my mom and dad to spend on a book. Hopefully it was on sale. The real treasure is Dad’s gift of CEZANNE by himself edited by Richard Kendall, in which Dad writes, “I am sitting here remembering that you said your suicide song will be ‘The Christmas Song.’ Mine shall be the ‘Hockey Pokey.’ It pretty well sums up life.” That was from Christmas 2001.

At the time, I read the inscription and asked him, “What do you mean ‘it pretty well sums up life?’”

“Well,” he said, “that’s what it’s all about.”

Of course, I thought. Of course that’s what it’s all about….what else?

Dad signs off his inscription, “I love you, Dad.”

I love you, Dad. I get up and return the book to the shelf. It wasn’t very long ago that I felt disappointed whenever Dad signed or inscribed a book. I thought the book lost its value. I was wrong.

***

When I am fortunate enough to visit with artists in their studios, I am thrilled whenever I can look through their cast-offs or at those pieces they deem “not very good”—their scraps, as I think of these pieces. For me, this is seeing the process of an artist and, in some instances, seeing the artist become the artist. Frank Gerrietts’s studio was brilliant for this. He kept stacks of drawings, watercolor samples, splotches of color on various grades of paper, paintings half begun, and half-finished scribbles. He had a backroom in his house that he called his studio. This backroom had a door that opened to a deliberately overgrown yard. Practical cats came in and out of a cat door leading into this backroom. One of them, I remember, was named Paintbrush. In Frank’s studio there was a large table. The table was where he painted, where he framed, where he set his coffee cups, and where he kept stacks of notes and papers. He would perform technique demonstrations on the table. For instance, he taught me how to draw a bowl with a series of ovals that made the bowl appear more grounded. He showed me how to draw sea gulls in flight by slanting m’s to suggest the shape of wings.

Every so often Frank would pick up what he called a failed painting. Usually it was a watercolor. He would hold up the painting and point to some corner or postage stamp in the picture and ask me, “See that?”

“I see it.”

“What do you see?”

“I don’t know. Maybe a nice spot in the painting?”

“That’s right. Now watch.”

Frank then worked a kind of magic. He would bend the paper and tear out the section we had studied. He threw the paper onto the table, and with color pencils and watercolor he began, as he said, “to push color around.”

“See what I’m doing?”

“I think so.”

“Watch closely.”

Soon a field or ocean or treeline or flower or even a village would emerge.

“See, kid. Sometimes you got to find the painting in the painting.”

He checked his work again. “Not bad.” And signed it Freddy Gomez.

“Who the hell is Freddy Gomez, Frank?”

“That’s who painted the picture.”

“But you painted the picture.”

“Not that one. That’s a true Freddy Gomez.”

Frank signed all of his paintings that were not up to his standards as Freddy Gomez. Dear Frank. I miss him.

Sorting through my books and thinking of Frank’s studio with his rickles of paper and clutter, I am reminded how much I enjoy scraps. I enjoy the word “scrap.” The word, appropriately enough, comes from an Old Norse word skrap. Going by etymonline.com’s definition, the Old Norse meant “scraps, trifles” and comes from the verb skrapa “to scrape, scratch, cut.” Translated into my idiomatic preferences, when looking at books or shifting through an artist’s studio or browsing through postcards in a dime store, I am scratching the surface. What I am not doing is treasure hunting.

***

I’ve not given much attention to Antiques Roadshow or Pawn Stars or their many variants, but I recognize the tingle that someone experiences at finding something of extraordinary value. Television producers know very well it’s better for viewing numbers if there is a great story attached to a valuable object. Say the Picasso purchased at a thrift store, the Billy the Kid photo found at a curio shop, or the teapot that someone decided to keep after seeing what was left of their grandmother’s estate sale, and—low and behold—the teapot comes from fill-in-the-blank Chinese dynasty! Soon enough, those of us at home will learn the price, the value of the said object. That’s where our anticipation lies.

But that’s not what I am talking about here, that’s not the value to which I refer. Rather, I am talking about the equation between value and meaning, where meaning becomes the value. The meaning, for example, that comes when we decide we are not going to sell Ernest Hemingway’s hunting purse, the one we endured so much heartache and profound bullshit to acquire. It’s not for sale, no matter what the offer is…unless, of course, we are in a serious pinch. Which I’m not.

Many of us know something of both conditions. We appreciate objects of unexpected value and objects that, as we say, can’t be bought. In the case of the former, the deal is sweetened further when we discover an object for which an owner has underestimated the value, which is especially tasty for us bibliophiles. Imagine finding a true first edition of Falconry in the Valley of the Indus at a flea market for 10.00 USD. That would be quite a find. In a larger market the same book would be priced considerably more than 10.00 USD. At the same time, if we are a fan of Sir Richard Francis Burton or explorers or falconry or handsome old books, then each and all are reasons enough to keep the book—as opposed to dumping it on the rare book market in the hope of the highest bidder. But we never know what we’ll find. One minute we are facing a toilet and happen to glance above the tank and right there, right above the tank, right above the ubiquitous basket of soaps and lotions and extra toilet paper is an original sketch by Matisse.

In the here and now, and a long way from some toilets I have known, I am at my desk. It’s messier than when I began writing this essay—messy with my own scraps. A few more books have migrated to the desk. There is Madame De Pompadour by Nancy Mitford, which I found in a junk store in East Texas. The book is in splendid condition. There is a four volume set of Richard Jefferies’s work, which includes Bevis, The Gamekeeper at Home, The Open Air, and Round About a Great Estate & Red Deer. These are 1948 editions, but each volume has the original dustjacket in fine condition. I purchased the set from a small bookshop in Harrogate, England, a few years ago. The shop was one of the best bookstores I’ve ever entered. It was like something out of Dickens, as though Mr. Fezziwig ran a bookstore instead of a warehouse. A couple of years after my purchase, the bookshop was gone, as were many of the bookshops in that town. Back on the desk and on the other side of Tu Fu and Silk Roads is H. C. Baldry’s The Greek Tragic Theatre, which happens to be signed by Bernard Knox, identifying the book as his own copy. This was an exciting though accidental find. Bernard Knox wrote, among other works, The Oldest Dead White European Males and Other Reflections on Classics, plus memorable introductions to Robert Fagles’s translation of The Iliad and The Odyssey. Beneath the copy of Theatre lies a 1953 Reprint Society edition of The Old Man and The Sea, gifted to me with love by Lady Cassie in 2006. At the bottom of the title page, below where Lady Cassie penned her love, is another inscription, one written in pencil and a confident script that reads, “To Dad with love, best wishes for Christmas 1954 from Tom & Vera.” Who is Dad? Who are Tom and Vera? Why did Dad’s book end up in some bric-a-brac shop? None of these questions will be answered.

Leaving the library and crossing the kitchen, I enter the living room where there is a tired looking bookshelf placed between a Laura Jackson apple painting and a slot canyon painting by Scott Geary. On the second shelf there are 20 volumes of the Harvard Classics. Volume Two is Plato Epictetus Marcus Aurelius. In this book my father penned the following note:

My Son,

I bought these books for you before you could read. I did this that I might read them before you, and I have underlined some passages that I would like for you to meditate upon; I have purposely not indicated my approval or disapproval of these things that I have underscored, in order to encourage you to do your own thinking.

Near the bottom of the page, below my father’s handwriting, there in a notation that reads I Cor 1:19. I had to look up the scripture. The verse reads “For it is written, I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and will bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent.”

That’s as far as I’ve gotten.

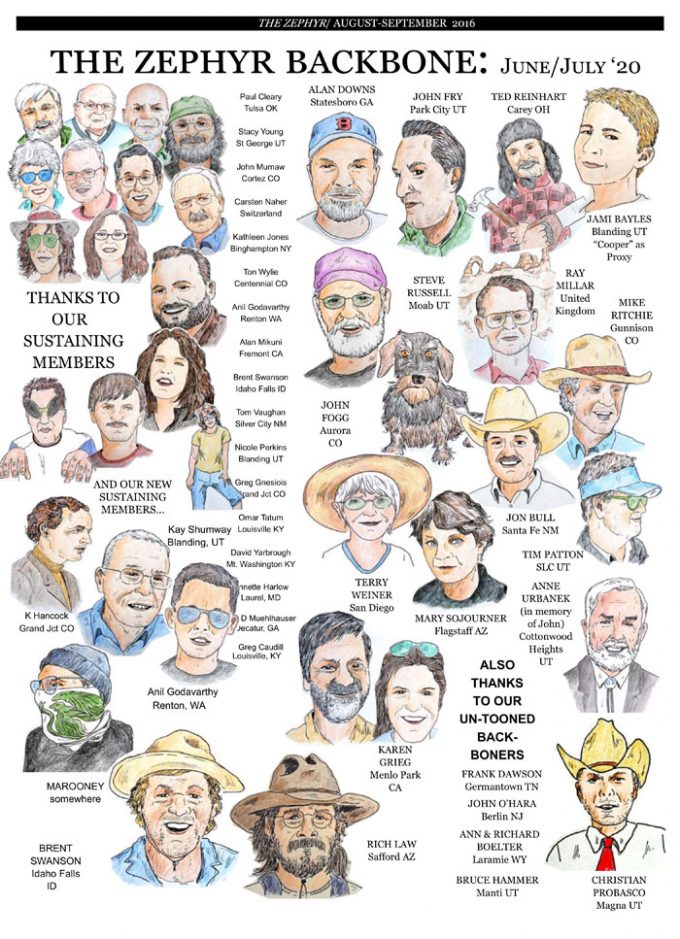

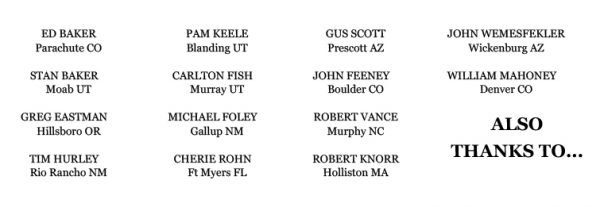

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently The Scent of a Thousand Rains and the forthcoming film Koppmoll (2020), which explores memories of War World II and home. You can find out more about his work at: damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Beauty and art are in the eye of the beholder, and each one of us has to decide the worth vs. the cost …. thanks for the writing… it is both beauty and art. Michelle

Was it a poke in the ribs- he has 9, I counted them aloud- that brought down Mr. Pokey?

Wow Damon You never cease to amaze me Thank you for making my day