It’s a peculiar time to live in a tiny, isolated town on the prairie. Peculiar, firstly, because the town looks largely the same, despite the international pandemic that occupies every headline and every conversation. The roads are quiet, yes. But they’ve always been this quiet. I think of the afternoon when Jim and I first arrived in this little dot in the grass ten years ago—ten years exactly. We drove down the Main Street and wondered out loud to each other repeatedly whether anyone lived here. It was 110 degrees and humid. We were the only car on Main Street. The houses wore signs of habitation—flowers in the gardens, and chairs on the porches—but all the owners were intelligently cloistered behind their front doors. They were blasting themselves with air-conditioning. They weren’t out on the sidewalks, wilting and collapsing in the steam bath afternoon. I remember that day constantly, the cusp of our finding this home. This little town.

Now, when we pass the local pizza place, with its large “Carryout Only” banner, I remember that same night, ten years ago, when we stopped in for pizza and were relieved the find the town had people in it after all. The cavernous room was bustling, by small town standards. Maybe a quarter of the tables were filled. Families laughed and jockeyed with each other for the largest slices, with babies draped over laps and or toddling at their parents’ feet. A group of Mennonite farmers had driven in to town, and they occupied the largest table. A woman in a homemade pink-flowered bonnet bragged audibly about her cucumbers. In the adjacent arcade room, a few teenagers fidgeted and ricocheted off each other like spinning tops. This was the height of local life. As the sun fell, the little movie theater marquee lit up in neon. Now that night feels like another world.

Ten years later, pandemic life has left its mark here. In mid-March, the biggest news in town was that our varsity boys basketball team had advanced into the semifinals in the state tournament. It was every sports movie rolled into one—the rural, underfunded school with barely enough students to fill a team had somehow pulled off victory after victory, through a magisterial season. We were just days from the Championship game. And then the first deaths were announced in another corner of the state, in Wyandotte County. The curtain dropped. Suddenly. Staggeringly. The games were canceled. The bus carried our boys home, and the town reeled. Then schools were canceled altogether, along with Prom and Graduation.

The pizza place, and the other two restaurants in town, became takeout-only overnight. The bank lobbies were locked. The Hardware store was locked. The County Courthouse, locked. The movie theater removed the posters from its facade, and turned off the lights.

Two months passed in that lockdown world, and now we’re in the process of the “re-opening.” Graduation was eventually re-scheduled and held outdoors in the football field, with limited family members spaced apart in the bleachers and cars honking support from the sidelines. Meat prices have doubled in the grocery; they remain devastatingly low at the auction ring. In general, belts are tight. Conversations about the future are all held in a caveat tense; each sentence begins with “maybe…” or “Well, if things get better…,” or “Well, if the numbers get worse…”. And just at this moment—right as we were tentatively considering retracing our steps to ‘normal’ life—in the latter days of May, our sweet little hidden spot on the map has announced its very first case of Covid 19. The international curse has finally reached out a finger to touch this isolated place. And the question around town is…now what?

We’re accustomed to disasters of the quick and dirty variety. Severe thunderstorms that blow through in the night. Wildfires that rage through the fields at 60 miles an hour. Even our more patient foes, like the excruciating pains of regular droughts, are visible. The sun sears the dirt; the grasses crunch into dust. But this has been different. The virus is invisible and, until very recently, distant. The numbers from New York and the other hot spots have been alarming, and locals in town shook their heads and sighed, “Those poor people in the middle of this thing. It’s awful for them.” But, for two months, it has been a tragedy at arm’s length—on the news, in the scroll of our news feed—and not an immediate threat.

In contrast, the financial pain of the lockdown was both visible and local. And, in the time it’s taken for the virus to reach us, locals have developed a furious range of opinions on the economic hit to our businesses, the gut punch to ranchers and farmers, the ceaseless wave of job losses. A few reactions were extreme. Yes, I’ve heard some conspiracy theories. I’ve heard insults to our Governor, to Liberals, to Dr Fauci, etc etc etc. But I’ve also heard voices of intense practicality.

The meme I saw shared across a number of more progressive pages on Facebook, which attributes the spread of the virus both to the density and to the density of the population, was also popular among more conservative voices here. Why, they ask, should our little county, with a population density of 2 people per square mile, have faced the same restrictions as urban Johnson County, Kansas, which has a population density of 1,167 people per square mile? Much less the same restrictions as New York City, with 26,403 per square mile? What, do you think we’re stupid? You think we have a hard time keeping our distance here?

It’s a reasonable question. So many of the restrictions, particularly for smaller towns, seem predicated on the assumption that people can’t be trusted to take basic precautions for themselves and their communities. It would have been a rare night before the virus, even after a triumphant football game, when tables of customers at the pizza place were seated closer than 6 feet from each other. It would have been exceedingly rare for the number of people in any building in town to exceed 25% of capacity. We have a lot of older and more vulnerable members of our community, and it isn’t difficult to rally local support in favor of protecting them. If our local leaders had gathered with business owners, ministers, and health officials from the outset, and listened to all their ideas, it’s likely they could have crafted logical restrictions—different in tone, at least, if not in scale—from the rules that sparked division and anger. And, dear God, if only the CDC hadn’t bungled the mask question from the outset, I believe we could’ve easily gathered public support in little towns for mask-wearing, in addition to locking down the nursing homes, support for business capacity restrictions and cancellations of large gatherings. In a little town like this, people can be persuaded more easily than they can be coerced. Maybe it still would’ve been a fight, but the opposition side would’ve been far smaller. If nothing else, there’s a psychological benefit in letting people feel more a part of the process, and less like children being talked down to.

But now I need to stop and note that I’m just talking about my little town of 750 people. It’s become more apparent than ever that the world of small rural towns and the world of cities have little in common these days. And, faced with the question of how to manage dense metropolitan areas, and the nation as a whole, I plead humility. This virus has killed 100,000 Americans so far, most of whom live in densely populated areas. While I see the dynamics from my neighborhood play out similarly on the larger stage, I have nothing but compassion for anyone needing to manage huge populations of people during this nightmare. There’s sound logic behind a whole wide variety of differing lockdown and re-opening approaches. I can’t find my way to a clear answer on any of it.

When I look at the large scale, my objections change. I become concerned more with the manner in which we’re speaking to each other and (not) listening to each other. I’m concerned with the feeling of fatality toward the loss of millions of jobs and hundreds of thousands of small businesses. And also to the ease with which we’ve accepted this entirely tech-mediated world, in which isolation, separation and de-personalization are not only grudgingly and temporarily allowed, but are increasingly preferred to human contact.

It’s that fundamental separation in the country that has been on my mind, especially. The separation of Left and Right, and more precisely, of Urban and Rural. Not only does each side look down on the other. Each side seems to be fundamentally incapable of imagining the life of the other. This has been a worsening divide for years, far longer than the past few months, and I’m well-situated to observe it. Among my dear friends, I count many with “urban” mindsets—typically college-educated and working professional-class jobs. And I live among and treasure my friends among the “rural”mindset too—many of whom are working class, lacking in degrees, but blessed with a wealth of practical knowledge. I hear regularly how each side describes the other.

The Urban mind sees the Rural mind as closed-in, superstitious, conspiratorial, loony. The Urban mind believes that the Rural doesn’t comprehend the most basic functions of government, the last hundred years of scientific advancement, or how to reason and make meaning of new concepts or unfamiliar ideas. They forget the depth of knowledge held by small town teachers and ministers, historical societies, small colleges and rural lawyers, and the ingenuity and scientific expertise required to maintain a ranching and farming life.

The Rural mind, on the other hand, sees the Urban mind as smug, hysterical, abstract and, well, loony. The Rural mind believes that the Urban doesn’t comprehend the most basic facts about how a car engine functions, how food and energy are produced and transmitted, or the value of physical labor. It’s a common joke in the country that “city people” think their food is produced in a grocery store. They forget that cities are chock-full of carpenters and plumbers, construction workers, mechanics, cab drivers and butchers, millions of city-dwellers whose backs are as tired and whose hands are as dirty as their own.

I’ll grant, though, that when you live in a town of 750, the city can feel awfully far away. For example: a local delivery driver was chuckling, a few weeks ago, telling us about his niece who lives in the greater D.C. Area. She heard that her grandfather, back in Kansas, was headed out into the fields to fix up an old hunting blind, and she became furious with him. “Grandpa, you’re in danger!” She yelled at him on the phone. “You’re supposed to stay home! Don’t leave your house!” The old fellow was perplexed. He confided his confusion in his son, our delivery driver. “How does she think he’s going to catch it?” The driver asked us. “From the dirt? The grass?” He shook his head.

One of our neighbors has two daughters, both living in major metropolitan areas, who were giving her the same trouble. As early as mid-March, they were berating her on the phone for going out to the grocery store or the Dollar General store. “I saw a total of two people at the grocery store,” our neighbor said to me, laughing. “What do they think, we’re gonna cross the room and lick each other?”

It can feel like we’re living in two dimensions, occupying the same physical space, but somehow each incomprehensible to the other. We simply cannot imagine how it feels to be the “other” sort of person.

Then again, as the virus moves closer, I do feel some changes on that front. While our state is slowly reopening its businesses, the flare-up of cases at nearby meat-processing plants means that our rural counties are finally starting to reckon with Covid 19 as a daily reality, and not a distant headline. I hear fewer rumblings about the whole thing being a “hoax”. And now some of the fears of the city-dwellers start to feel more understandable. More of us are getting comfortable wearing masks, at least when we go to any larger town. We’re relieved to see the re-opening restaurants limiting their capacities and separating tables; we’re comforted by plexiglass barriers. I got a haircut last week, for the first time since early March, and I was the only person allowed in the salon during the appointment. I was directed to wash my hands before entering, and to confirm that I wasn’t feeling any symptoms. Magan, the salon owner, told me she was undertaking a 20 minute cleaning process between clients. And this is in conservative, rural Kansas. Believe me, most people are taking it seriously out here.

But, unfortunately, on the larger scale, this virus has become yet another front in the ongoing war of I’m right and You’re worthless. It’s the newest reason to yell at each other over the airwaves. The newest reason to be fearful, and alienated and glued to our screens. Three or four months ago, as this benighted year was just showing its true colors, I can remember thinking, People hate each other too much now. It’s reached unrecoverable levels. And then Covid-19 arrived, rolling in from across the oceans, and we all found yet another reason to decide somebody isn’t worth the ground they’re standing on. Another reason to distrust; to distrust your neighbor, who is standing too close to the mailman without wearing a mask; to distrust your state’s Governor, who closed too much and too soon or possibly too little and too late, or possibly began reopening too quickly or possibly too slowly; and don’t forget all the nameless, faceless Powers That Be, who are always conspiring against your well-being. There are more than 328 million other people in this country for you to distrust now. They are trying to kill you, or themselves. They’re taking away your livelihood and your dreams. That salon owner is a murderer; that exhausted governor is a tyrant; and on, and on, and on…

It’s so exhausting, and so loud, it’s easy to forget that you’re only hearing a few voices. The loudest voices. To those in the Leftward tribe, it appears that anyone who disagrees with a statewide lockdown must be like those mask-less protesters yelling epithets at the governors and waving around AR-15’s. To those on the Right, anyone who agrees with any of the lockdown measures must want to physically confine people to their homes for the foreseeable future and doom every worker to unemployment and every mom-and-pop business to failure. But, any time you talk to people individually—particularly if you catch them away from their social media feed—you find it isn’t the case.

A lot of people on the Left support temporary restrictions to help manage the virus, but also dread the effect on local businesses and harbor concerns about slippery slopes with privacy rights and personal liberties. A lot of people on the Right are intrinsically opposed to forced business closures and restrictions on their movement, but also support voluntary distancing guidelines, and want stronger protections for their local nursing homes and more resources for the hospitals.

When it comes down to it, most people aren’t villains. Everyone wants to prevent suffering—both the suffering of those who fall ill, and the suffering of those facing the despair of poverty. If you can begin a conversation from that understanding, and listen with an assumption of good faith, then you’ll find the problem from the outset was never that one side was evil and the other good; one side rational, and the other loony crazy. Your problem was those loud, screaming voices and the relentless media and social media machinery that convinced us that’s how the world really sounds.

I can’t help but think, if only…

If only we could maneuver our conversations onto less slippery footing, then maybe we could discuss the bigger problems, the more insidious effects of the last couple months. Like, firstly, how are we going to handle the staggering levels of unemployment and the likely closure of hundreds of thousands of small, locally-owned businesses? I live in rural Kansas, and I already know of two restaurants and a bookstore that won’t ever reopen. I shudder to think of the number of businesses in cities that will suffer the same fate—especially since they face maintenance and rental costs that aren’t nearly as expensive in small towns. No one, of any political stripe, wants these businesses to fail. We all want local restaurants, local bookstores, local retail shops and theaters to survive. We all want for everyone who had a job in early March to have a job again by August or December. So how are we going to do that? Does anyone have a plan?

It’s the Liberal-Conservative split that’s half the trouble. It convinces people they must disagree, when really they don’t. Right now I’m regularly hearing Conservatives talking about the deadly consequences of poverty. They’re talking about issues of addiction and mental health. People all over the country are realizing that their state’s unemployment systems have been failing for years, and how little a $1200 check covers. This is an opportunity to talk about rent control for commercial buildings, and the importance of local food production. Paid sick leave and Medicaid expansion. Fierce antitrust legislation. Diversifying and de-centralizing local economies. And none of it needs to be Conservative vs Liberal, or Urban vs Rural. These are issues that we all face together.

Of course, we can all wave our hands above our heads and yell for attention to the real issues, but the greatest feeling of fatality sweeps over everyone—myself included—when we look at the leaders to whom we’d appeal for help. What leaders? Exactly. We might be able to sit down with each other and find points of agreement. We might discover a similar view of what ‘quality of life’ means, and how we could improve our respective communities for the people who live in them. But, at the societal level, the current is pushing hard in one direction, and sweeping us along with our without our conscious agreement. Consider this: six months ago, were you trying to reduce the amount of time you spent looking at screens? Were you concerned about the increasing isolation of modern society? The increase in drug and alcohol-related deaths and suicides? Were you thinking about your online privacy, and trying to restrict the flow of data on your habits and movements? Now consider how all those issues have fared in the last few months.

Every trend that was already disconcerting about our societies is exactly the same six months later. The only difference is acceleration. We were already moving into a de-personalized and touch-less world, in which human fingers will be primarily important for their facility with tracing and tapping at objects; already, every transaction, financial or personal, was increasingly undertaken via the mediation of silicon and microchips, accompanied by advertising and overseen by benevolent data brokers. We were already on this path; we are only drawing nearer to the destination.

The screens are no longer screens. They are entertainment and comfort. The screen is where your family lives. Where your friends are, and where their new baby has been born. It’s where the neighborhood gathers. It’s where your boss is, and where your kid goes to school. We scrupulously avoid each other in the streets and the stores now. The digital world is where the people are. We still—despite everything—are reaching for people. Even if they feel slightly false, and their eyes never quite meet ours.

Maybe the most troubling aspect of this socially distanced life is that it renders other humans even less “real” than they were before. Already, we lived in a society where people exerted little effort to imagine the lives of others. The well-off couldn’t imagine poverty. The waitress in Montana couldn’t imagine the life of an accountant in Seattle. And vice versa. The Amazon warehouse worker in Queens couldn’t imagine the life of a rancher in Texas. And vice versa.

The tools of social media and online news media—increasingly, the only tools at hand for communication—only exacerbate the tendency to stereotype and dismiss anyone who doesn’t suit your narrative. Some guy on Facebook is against his state’s lockdown measures? Well, he’s just a “whiny baby” who can’t tolerate being “inconvenienced” in order save people’s lives. It’s a little harder to retreat to that position of smug superiority when you’re talking directly to someone who looks in your eyes and says, “If I don’t get some kind of paycheck in the next two weeks, I will lose my car. Then I will lose my house. I will not be able to buy food. The state unemployment website has crashed every five minutes for the past 8 hours, and for the past two days before that. Please, tell me what I’m supposed to do.” It’s hard to dismiss the restaurant owner who had a thriving business only a month or so earlier, who sits now at a table in his empty restaurant crying over the list of names of employees he’s had to fire. Those people are not babies. They were not “inconvenienced.” They were traumatized and cut adrift in a world that seems willing to abandon them.

And the people who are wearing masks and keeping distancing are doing so, not out of weakness or hysteria, but because they too are desperate for the feeling of a “normal” life. They want to live, while protecting the people they meet from pain or death. Jim and I had a conversation recently in which we considered every single person we know, and what condition—age, diabetes, hypertension, obesity—puts them at greater risk of dying from Covid 19. We thought of each individual friend and family member, and how devastated we would be to lose any of them. Among all the isolation and alienation, perhaps the most silent voices are those of the sick and the dead. Shuttered in hospital beds without visitors. Whisked away and buried without funerals. Now they are numbers in charts. How many have had their final conversations with their children and friends over the phone, alone in an empty room? Death shouldn’t be this silent. It shouldn’t be this invisible.

Someday, we will come out of this particular crisis. Maybe by degrees, so slowly that we hardly mark the hour when we don’t think about the virus anymore. Or maybe it will be all at once, in the exultant days and months after a successful vaccine, and a host of successful treatments. But, someday, there will be an ending. And then we will need to look back over the intervening months. We will need to evaluate ourselves.

An entire planet of humans is experiencing fear, anxiety and pain. Poverty is endemic right now. So is addiction, familial abuse, and suicide. Grief is everywhere. We are all in the same hurricane, if not in the same boat. And when we look back, we will have a lot to face. How did we behave? We need to remember all the snarky memes and dismissive comments. The conspiracy theories and the armed protests. How did we connect with each other? We’ll recall the flickering blue light of our respective screens. The silence of empty streets and dark, empty buildings. Who gained power? Tech companies, automated services, large corporations. Who lost power? Workers. Small businesses. Individuals.

And each of us, personally, will need to assess our own reactions. In a crisis that seems designed to make humans less human, to break the bonds between cities and towns, to turn us inward and divorce us from each other, what did we do as individuals?

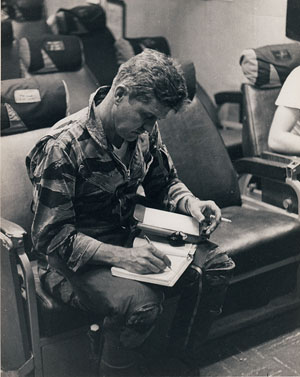

I’ve been reading lately about Admiral James Stockdale, the aviator and prisoner of war who retired from the Navy to teach philosophy at Stanford University. He’s achieved a certain fame among philosophers and psychologists for his remarks about surviving seemingly hopeless situations—in his case, the seven years he spent imprisoned and tortured in the so-called Hanoi Hilton. He’s known as the namesake for the “Stockdale Paradox,” which he outlined in an interview with author Jim Collins. The Paradox is often summed up simplistically as a philosophy of “hope for the best, prepare for the worst,” but the entire interview between Collins and Stockdale is interesting. To my mind, the most impactful moment is when Stockdale refers to himself as “the lucky one” for having experienced his years as a Prisoner of War.

Collins is confused by that statement, and disagrees. So Stockdale clarifies. He says, “Yes, because I know the answer to how I would do, and you never will.”

Most of us aren’t ever going to face circumstances as dire and seemingly hopeless as Stockdale’s were in Hanoi. But we do have an opportunity, right now, to observe ourselves in a state of heightened uncertainty and fear. The challenges aren’t imaginary. Unemployment, Addiction, Sickness and Death. All these terrors lie closer now than before. Someday, we will look back, each of us, and know how we did. Did we entrench into a strident position in one political camp or another? Did we judge and fight, and dismiss others as if they weren’t worth listening to? Or did we find greater reserves of empathy? Did we seek out opportunities to help others and model gentleness in our behavior? Above all else…were we kind?

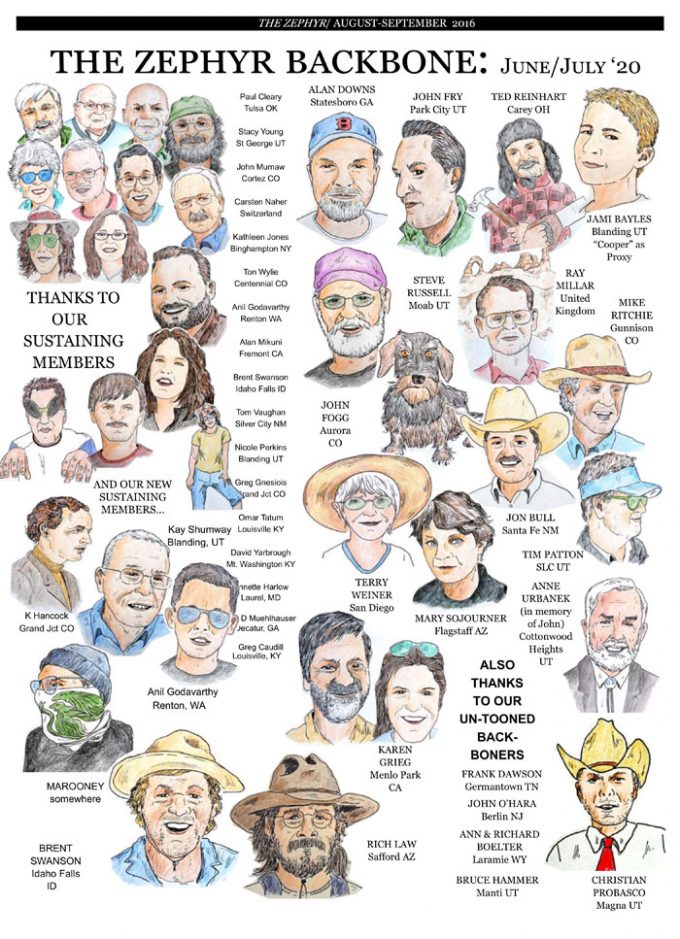

Tonya Audyn Stiles is Publisher and Managing Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

hi Tonya–I think you give Trump’s people too much credit. They suffer from clinical confirmation bias. Why do the slaves vote for the overseer? What makes them think that anarchy and oligarchy represent their best interests? Ask your ‘conservative’ friends this question. Me, I’m afraid to ask. I don’t want to get shot. Nonetheless, I can appreciate what you have to say here and, for the most part, I agree with you. Thanks, as always, for thought provoking thought!

Very fine timely article. Thanks

Maybe run for president, Tonya? You got my vote. I walk out in the damn near Forest Service clear-cut pines along a dirt road near my home. I curse the people who relied on computers and hubris to determine what the forest needs. And, I talk to the trees. “May those who killed your family, friends, community and infinite connections, may they suffer the same fate. May a species not human decide there are too many humans and thin the herd.” I’ve been having that conversation with the Ponderosa since early winter 2020, and I wonder if I have magical powers; and if so, where else can I use them?

Dear Tonya,

Thank you for this thoughtful article.

You raise urgent questions:

“Someday, we will look back, each of us, and know how we did. Did we entrench into a strident position in one political camp or another? Did we judge and fight, and dismiss others as if they weren’t worth listening to? Or did we find greater reserves of empathy? Did we seek out opportunities to help others and model gentleness in our behavior? Above all else…were we kind?”

Thank you for raising them and for helping us realize our responsibility to other human persons, worth our patience and kindness, created in the image of God.

Matt

I’m confused. I thought you and Jim lived in Utah. Did things get too crowded In Monticello? Did Jim get run down by a speedo-clad bicyclist? Did SUWA set up a field office there? A brew pub opening?

There aren’t any canyons in Kansas. No snow-capped mountains. Good luck.

For a revealing insight into how much we misperceive each other, and some factors that might add to misperception, see the Perception Gap Project website (no personal affiliation).

The project polled peoples’ opinions on a number of political and social issues, as well as political allegiances. They also asked people what they thought those on the “other side” believe about those same issues.

The depressing result is that partisan people hold exaggerated views of their opponents, overestimating extreme opinions by a factor of two. And more partisan people have bigger perception gaps. They are apparently busy constructing and then hating straw men that don’t exist.

Another depressing result was the correlation of bigger perception gaps with frequent media consumption, especially more partisan media that feed the echo chambers. Fox News viewers and New York Times readers are about equally wrong about each other. The biggest exception came from people who watch good ol’ network TV news. Those people actually have better than average perception of other peoples’ views.

And education does not help, especially for Democrats. With increasing college and advanced degrees, their perception gaps actually increased.

One encouraging result: our actual opinions are not that far apart. If we could somehow overcome the tendency to exaggerate our opponent’s views (and also overcome the efforts of politicians and media to exploit them), we might find it easier to cooperate and just get along.

Hi, Tonya. I want you and Jim to keep up the good work–and Bill Davis too (He’s my brother.) I may be a semi-urbanite (in San Diego County), but in my heart I’m a rural, small town person and would vote for any one of the three of you journalists for President. [Though who would want that thankless job?!] I love reading your Zephyr articles; they’re a bright spot in this quarantine time. Thanks.