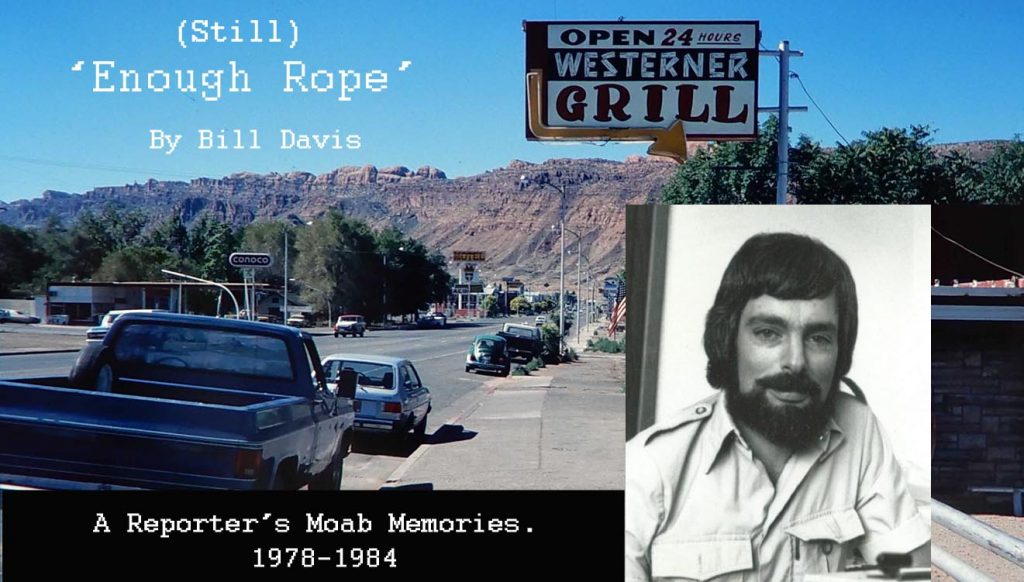

My first few days in town, toward the end of April, 1978, I wasn’t in town. Well, not sleeping there at any rate. Rentals were hard to come by (I gather it’s infinitely worse nowadays), so each evening I would sneak out to Arches after the entrance station closed, sleep in my car at the campground, and leave before the park opened in the morning. It was a lovely commute, and cheap, but a bit long, and amenities were lacking. Eventually, I would find a second-story corner apartment at 1st South and 1st East, where I stayed for a couple of years.

My first assignment for the paper was an evening BLM hearing. My tortured story spent a lot of space explaining wilderness designation issues most of my readers knew infinitely better than I, and with which they had been dealing for years. The only person I recognized during the hearing was Ed Abbey, who at that time still lived in town. It was the first of hundreds of government meetings I would attend and write up over the years. My first offerings now look embarrassingly amateurish; hell, they looked embarrassing the week after I wrote them. But I learned.

I had also suggested doing a ride-along with the local cops, to get a feel for the place. I set up a ride-along with Grand County’s Chief Deputy, Lynn Izatt. I wasn’t planning to do a story particularly. I simply wanted to get a feel for the area, and how it was policed.

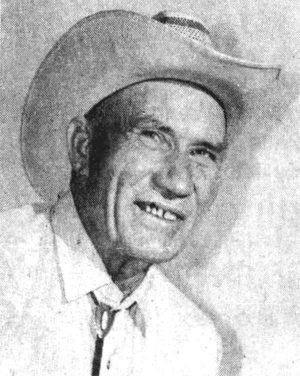

I had pictured cruising around the community with a uniformed city officer, but this was the Grand County Sheriff’s Office in the spring of ’78. Instead, and fortunately, I got Lynn. Lynn was, in a phrase, the ultimate image of the traditional Western deputy.

He was of average height and trim build, with an impressive mustache (I later noted lots of the local LEOs had them), and appeared to have stepped out of “Silverado.”

The Lawman.

He wore cowboy boots, jeans, a snap-front western shirt with a sizeable star pinned to a pocket, a cowboy hat, and a revolver with a handful of spare shells on a minimalist belt, a far cry from all the crap officers are loaded down with today. This was standard wear in the S.O.

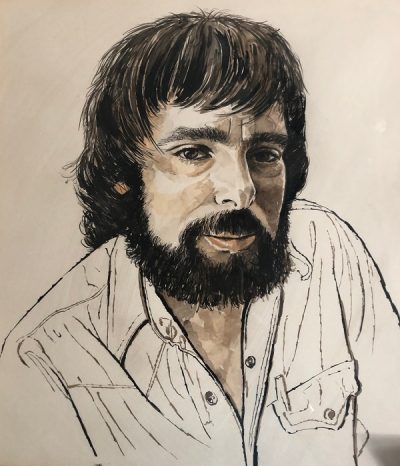

“I wonder how he feels about long-haired former musician/hippie-like, unhealthily skinny people?” I asked myself, given the remaining band hair and beard, and the Seventies in general. The New Guy. And he’s a reporter.

Revealing some of my own prejudices, I was concerned the deputy and the new reporter might not hit it off, and would have an uncomfortable day. I needn’t have worried. Instead, within minutes of settling into his brown, mostly unmarked car with only a single unique rotating spotlight on the fender (chrome to the front during normal operations, swiveling to red when someone was about to get in trouble), I found him to be warm, friendly, and easy to talk to, starting a friendship that lasts to this day.

I learned that Grand County, at 3,684 square miles (or 3,694, depending upon your source), one of the largest counties area-wise in the Lower 48, was handled by three, and only three officers: Lynn, fellow Deputy Roger Coursey, and then-Sheriff Heck Bowman. San Juan County to the south was bigger, at 7,933 square miles, but much of that was the Navajo Nation, which had its own police force. The population of the county was about 8,000, and of Moab City (which had its own police force), around 6,000. A handful of Utah Highway Patrol troopers rounded out local law enforcement, along with one lonely FBI agent, who spent most of his time on the Rez, and must have done something really awful to get assigned to Moab (Unless he liked it, of course; I never asked). I always thought the Butte, Montana office was the ultimate punishment.

During the thoroughly enjoyable day, I learned Izatt had previously worked for Cache County at least part of the time when I went to school in Logan, so we had that in common. In addition, his darkroom and photography skills at least matched my own. We would come to trust one another a great deal. I also found, much later, that he played guitar, another point of connection, although I wasn’t about to reveal I played, at that point (see last issue’s column). In fact, throughout my tenure, I pretty much kept any musical skills I had under wraps. It seemed safest, and I thought at the time I might never pick up a guitar again anyway. It wasn’t bitterness exactly—more like horror. Besides, you can’t exactly crank out Heart’s “Magic Man” sitting around the campfire.

The ride-along set the pattern for many others I took over the years: If you want absolutely nothing to happen, bring along a reporter. The only law enforcement activity that occurred was when Lynn stopped to holler at a naked couple enjoying each other’s company on a beach along the river road. They no doubt thought they were way out in the boonies, instead of along the Castle Valley school bus route (That beach is probably a 30-unit campground now). In any case, they were giving hippies a bad name. Of course, on a 1970 college spring break (from Logan; it was bloody cold) I had done the same at Arches’ Double O arch, figuring we were in the wilderness. At that time no one was around, even though it was near a main hiking route, unlike, I assume, today. Besides, I never claimed to be immune to occasional hypocrisy.

Between fleeing the band and starting a real job again, I briefly visited my folks in Paradise, Calif., the town wiped out many years later by fire. While there, I purchased a 1973 Volkswagen Safari, known almost universally as a Thing. The model was VW’s idea of a cutesy Nazi staff car. Almost nobody bought them.

I found mine used for the then-significant price of $1,200, which I borrowed. That last fact becomes important in a bit. The car was perfect for my needs. With a metal body, it was no dune buggy, but it had modest off-road capability, a convertible top, and you could take the doors off, as long as you didn’t mind losing the outside mirrors.

As time passed, an additional benefit of having a rare, if ugly vehicle developed: It was recognizable, a fact Sam even noted in his goodbye (my goodbye, not his) column years later. Cops, firefighters and ambulance EMTs all recognized me from a distance, so I was usually waved through to whatever it was. I mounted all kinds of lights on the front for nighttime photography, which worked well, except for the one time the auxiliary battery set the backseat on fire, but we’ll let that go for now.

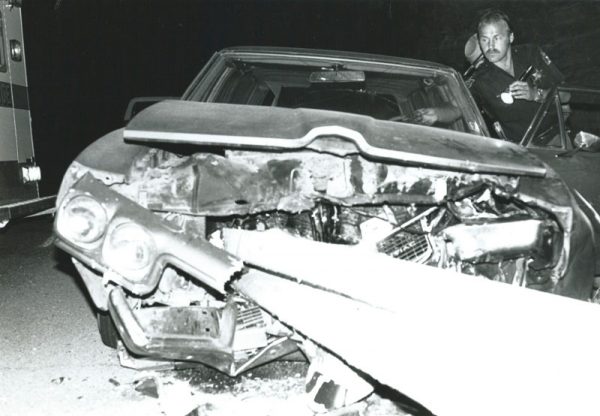

A side story: Once I was headed north on 191 late at night for some newsworthy reason, when this idiot kept flashing his high beams, starting from a long ways away. I flicked mine to show this is high, this is low. He flicked a couple of more times, then turned on his brights and left them on. I was getting steamed.

“I’ll show that son of a bitch some lights.”

I waited until he was almost abreast, then flicked on everything, even the fog lights, just for color. Take that, asshat.

In the mirror, I watched the other car weave across, well, perhaps more than one lane. Fortunately, it was one of those Moab nights where you could see opposing traffic 15 minutes before it showed up, and no other lights were visible.

Author’s Note: In light of the fact that I’m writing about local law enforcement, I should note that the above action should never be taken by anyone, anytime, is extremely dangerous, and probably never happened.

Toward the end of my first week at The T-I, I scored the apartment at 1st South and 1st East I have previously mentioned. I found it by asking everyone I met if they knew of any rentals, and one thing a new reporter does is meet lots of people.

The place was a bit Spartan, but was also airy, light filled, and warm water came out of the wall; that was plenty good enough for me. I settled in to the apartment with my Thing (Come on, you knew with that car the lame jokes were coming. I heard them for years).

One huge advantage of the apartment was its location one block from The Times office. Previously, we usually commuted about 200 miles in the band, and prior to that, my motorcycle commute to Denver was 100 miles round-trip. I rode it, once, in the snow. Idiot. Well, it was snow only halfway, and only on the way home.

In any case, Monday night during my second week on the job, and first in my new home, I learned that the convenience of the apartment came with a price, and a lesson.

I was home, and tired, a condition that didn’t let up for the next six-and-a-half years. I hadn’t even bothered rolling up film to take home. I mean, I’m in my dreamed-of small town; nothing’s going to happen, and I’m off work. I was just nodding off on the couch when I noticed a flickering orange light dancing across the ceiling. Pretty. No. Hold on. I think the ceiling’s on fire. Jump up. Look out the window.

No, it’s just the Green Well addition under construction, fully involved in flames. Three things became obvious: 1. Apparently, the entire world south of my apartment was burning 2. The apartment was getting warm, and 3. I had no film. Shit, shit, shit!

I grabbed the camera bag, dashed down the back stairs, ran past the Atomic Motel and cut across the Social Services parking lot to The Times. Fumbling for the key now, calm down, calm down. Into the darkroom, grab the film loader and some 35mm cans. My hands are shaking; I’m dropping lids and canisters. Two rolls, let’s go, run home.

The fire involved a two-story addition, which was all open two-by-four framing, with the boards perfectly spaced for ventilating fire. By the time I got back to 1st South, both sides of the building facing the street were a wall of flames, and the heat so intense across the street the firefighters were sheltering behind the trees in front of my apartment building.

I joined them behind my own tree, the heat so intense I could only look ‘round it for a second or two to see—my car. My new car: the one I owe twelve hundred bucks on; its convertible roof is smoking. And the taillights are dripping.

I shouted to the next tree, where a firefighter with a hose was crouched, “When that thing gets charged, forget the fire, spray me and that car!” Amazingly, he said okay.

The hose straightened with a snap as the water arrived, and I dashed to the car, the radiant heat from the fire almost a physical push. The water hit me as I grabbed the door handle—too hot to touch but I opened it using the tail of my shirt. The top was really smoking now. The seat burned my back and thighs. The plastic steering wheel sizzled my fingers. In the midst of all the light and heat, I wondered idly what would happen when I turned the key. I mean, gasoline and all, you had to wonder.

I closed my eyes—really—and turned the key. She fired right up. Good Thing. I backed up with a thump, running over a charged line, doing it again to a second as I shot forward, with multiple male voices screaming, “Don’t run over the hoses!”

One of the lessons from the night: Never, and I mean never, run over a charged hoseline. For one, it can damage the hose, but far more important is what happens to the firefighters at the end of the hose if their water is interrupted, even for a second. During my career, and after, I have never, and will never, drive over a hoseline. But I did that night.

As I bumped over the hose and hopped the curb to get around the backside of the building, a soft plop announced the plastic back window had melted out of the convertible top. Every plastic surface inside the car was melting.

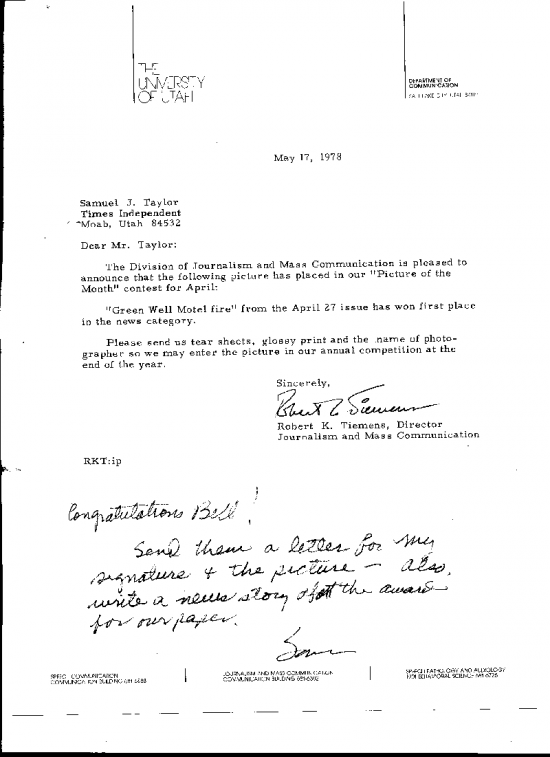

After getting the car behind shelter, I grabbed the camera and started shooting. Initially, I used flash, but I knew the resulting photos would look unnaturally well lit, nothing like the contrast of light and darkness one saw at the scene. Hoping to catch a more natural view, I turned off the flash, crouched behind a pumper streaming water through a 1,000-gallon-per-minute deluge nozzle, and used the flames to backlight the truck and water. That got The Times a News Photo of the Month award from the University of Utah, my first (Readers should note that journalists are always giving each other awards—probably because no one else will).

So, at the end of the day, or night, the price was paid and a couple of lessons learned: I was never again without a camera bag and three 20-exposure rolls of film, and later, a pocket scanner, and I never again blocked my car in at a fire scene.

Hours later, that night, now exhausted and stinking of smoke, I flopped into bed with the final lesson: This kind of work doesn’t stop at five or take weekends off.

Welcome to Moab, kid.

Afterword, the first: Police Chief Mel Dalton later speculated the Green Well fire might have been arson, and said there was a possible connection with suspicious fires in Moab and Monticello.

Afterword, the second: Two major mysteries remained after the fire: “Why is Green Well two words?” And “Did they really use the same green sauce on both their chicken enchiladas and egg foo yung?”

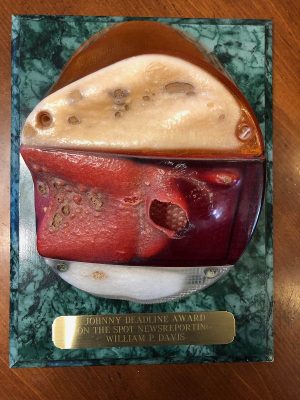

Afterword, the third: After several years, I finally replaced the melted taillights, keeping one as a souvenir. As an inspired Christmas present, Kris had the lens mounted on a plaque with a metal plate, giving me the “Johnny Deadline On-The-Spot News Writing Award.”

I kept the plaque on the wall of my office for the 24 years I was a professor. I hope to donate the award to The Times-Independent after I’m done with it (following what our financial adviser calls “end of retirement”), if they can find a spot on the wall.

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Reno, NV.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Giggled all the way through this story…I know the buildings and streets and rocks Bill mentioned. Wish I’d have been there and met him. And the Thing. (I’m partial to VWs of any denomination!)

I want Bill to know that I enjoy his style of writing, his sense of humor, his photographs and sharing his memories.

Loved Bill Davis’s “Moab Memories”! What fun it must’ve been for his Journalism students in his class! Would liked to have been a student there! Donna Andress, LV

It’s great to read about pre-deluge Moab. Bittersweet but still tasty, like the grub at the Westerner.

Those were the days, my friends……..

LOVED this. Thanks, Bill, thanks Zephyr!