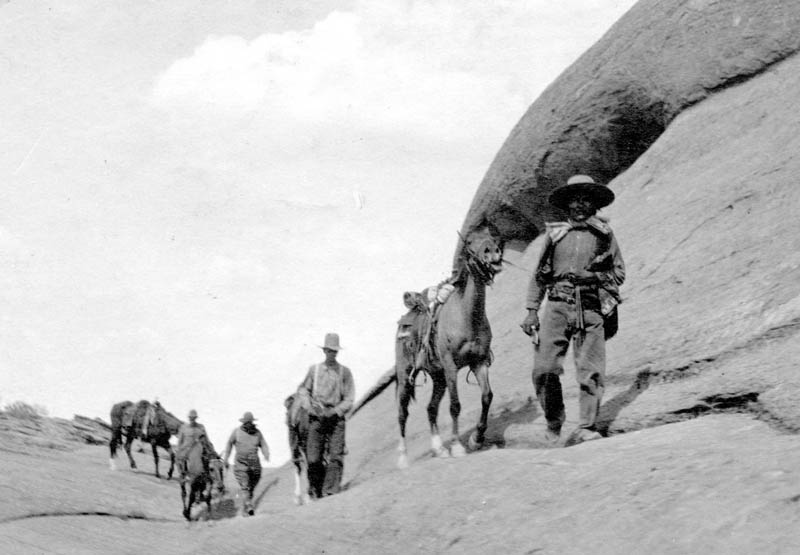

We took mules, all of us, as we expected the very roughest kind of trailless work; and we got it…. Wetherill said, while we were in an oak thicket on a very sharp slope at the foot of a canyon, “This is the kind of work the early pioneers had to endure—without it America would not have been opened up.”… Our work today was probably the toughest I had ever undertaken.

—Charles L. Bernheimer, gentleman explorer, May 30, 1926

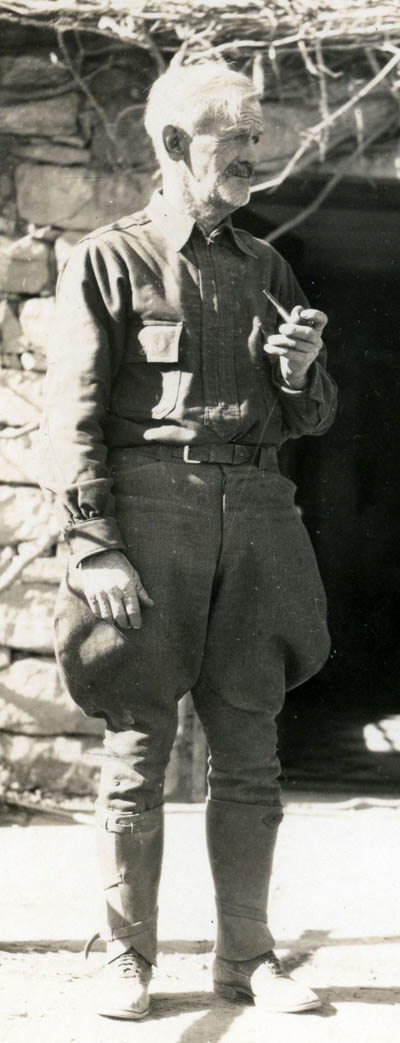

In about 1940, my aunt, young Johni Lou Kilcrease, was visiting her elderly grandparents at their home in the Utah/Arizona borderlands country at Kayenta, Arizona when she saw her grandfather, John Wetherill, laying out his bedroll on the hard ground outside the house. “Daddy John, why are you sleeping out here when you have a nice, comfortable bed inside,” she asked.

“Because I don’t want to get soft,” he replied.

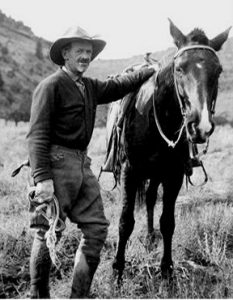

Wetherill’s life had been one of considerable hardship, which he had faced with strength and good spirits. Now, due to his age and declining health, his adventures in the outback of the Four Corners country were only memories. But he still believed in the value of determination, endurance, and resilience that had characterized his life from early on.

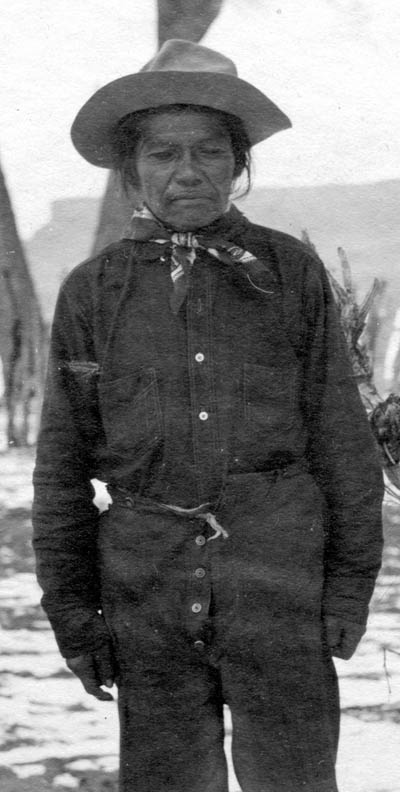

John’s resolve to maintain his stoicism and stamina reflected the ways of his Navajo neighbors who were taught, when they were children, to harden themselves against conditions they at first perceived as unpleasant, even though they were really harmless. His elderly friend, Wolfkiller, had recounted one of those times, during his youth, when his mother told him and his brother to go out and roll in the snow. He complained, saying he did not like to do it.

“My children, that is the reason I want you to do it,” his mother admonished. “It is because it seems cold to you. The snow will be with us for several moons now, and if you roll in it and treat it as a friend, it will not seem nearly as cold to you.”

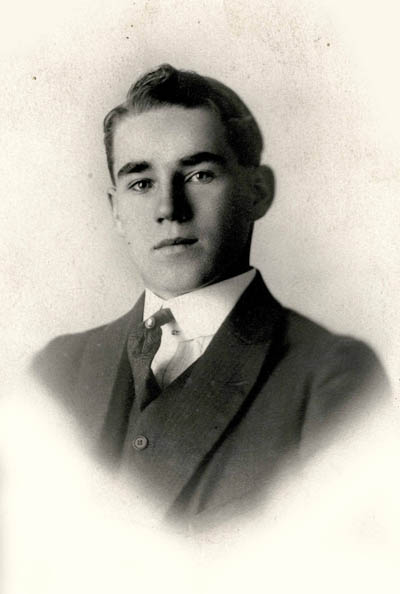

John Wetherill was born on Diamond Island, Kansas, on the Missouri River, in 1866. From his early years, he experienced the vicissitudes of hardscrabble life on the fringes of civilization. He undoubtedly heard stories of the grasshopper invasion that occurred just at the time of his birth, which denuded fields and destroyed crops, and about the flood a few months later that forced the family to leave their island home and relocate to the nearby town of Leavenworth. Knowing about these types of natural events, or so-called “acts of God”, did not dissuade him from developing a deep love of and respect for nature.

John and his siblings had many places to explore on the outskirts of Leavenworth, and he came to develop a passion for the power, bounty, and beauty of their natural environment. The deep gratification he received from spending time in the outdoors made any discomforts associated with his excursions seem trivial and inconsequential. He learned to conquer his unfounded fears of nature and develop skills to protect him from its legitimate dangers.

When John was fourteen years old, his family moved to the tiny village of Mancos near the southwestern corner of Colorado. Out their door to the west and southwest was the vast backcountry of Mancos Canyon, Mesa Verde, and the Four Corners region beyond. The Wetherill boys quickly learned how to raise crops, wrangle cattle, bust broncos, hunt, fish, explore, and survive in the outdoors with only the barest of comforts. They became friends with their Ute neighbors who needed no instruction on how to prosper in their natural environment without the so-called conveniences of modern society.

In 1900, John moved his young family—wife Louisa and children Ben and Georgia—to an isolated location in the badlands of northern New Mexico to trade with the Navajo people. From then on, the Navajo country was his home and the rough life was his routine. Besides running the trading post, he developed a clientele who engaged him to outfit and guide them on horseback treks into remote and sometimes distant places of scientific or scenic interest. In 1906 he moved the family to Oljato, Utah just west of Monument Valley, and in 1910 to a final home about twenty miles south across the Arizona border at a place they called Kayenta.

Many were the trials the family faced down through the years. While they were in New Mexico, an extended drought dried up the water holes, which caused their business to dwindle and necessitated relocation of the livestock to greener pastures up north in Colorado. Throughout their years in the Four Corners region, they confronted winters that were sometimes bitterly cold, and summers that could be blisteringly hot. Sandstorms occurred with some regularity. But the landscape was beautiful! Mesas, monuments, and canyons dominated the scenery, and the greenery, moisture, and shade of riparian areas contrasted with the various warm colors of sandstone and the aridity of the desert. The radiant heat of the sun on a cold morning, the freedom from machine-made sounds, the beauty of star-lit nights, and the changing colors as the sunlight played across the landscape had a deep effect on their souls.

John Wetherill’s wilderness excursions had their own challenges. Route-finding through the convoluted terrain, location of life-giving water sources, protection from heat and cold, and unplanned problems of one sort or another were just some of the difficulties that he faced. Yet he was most at peace when he was out in the rough territory. “The desert is home,” he declared. The stamina and skills he sharpened while he was out on the trail were invaluable when helping him deal with life’s more serious hardships.

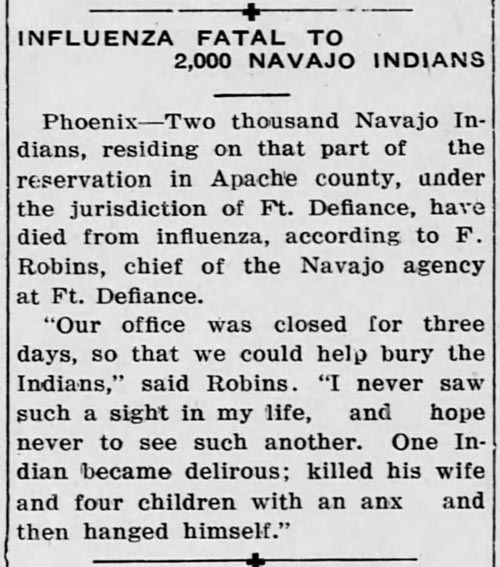

Of those hardships, none was more intense than the 1918 influenza pandemic. The tragedy in the Navajo country was orders of magnitude worse than the current heartbreaking situation. In the Kayenta district, a newly-arrived government school official, Albert B. Reagan, unexpectedly found himself with the job of ministering to the afflicted and burying the dead. “Probably no other people in the United States suffered from the ravages of this plague at all comparable with [the Navajos],” he wrote. “The influenza broke out at the boarding-school at Tuba City, Western Navajo Agency (Arizona), October 12, and in the other reservations of the Navajo Country at about the same time.” After only about two months, an official at the Fort Defiance Agency estimated that two thousand Navajos had died within that jurisdiction.

One researcher described the horrific effects of the disease. “Struck with blistering fevers, nasal hemorrhaging and pneumonia, the patients would drown in their own fluid-filled lungs.” The suffering was indescribable as people suddenly became violently ill in their remote homes and had no recourse for medical help or comfort. The virus spread like wildfire across the land. Entire families were wiped out. Reagan told of a family of eight who “were picking piñon nuts when the disease overtook them. When found later they were all lying dead around their wagon.” Some of the people who survived the virus died of starvation.

Sometimes it seemed that the spread of the disease would never stop. “There is a hush on the Lukachukai valley as well, much like the lazy, leaden clouds of mist that drag along the foot of its mountains on a rainy day. When will they be lifted? When will this dread disease end?” asked Berard Haile, one of the Franciscan missionaries in the central Navajo district. “Young men and women, faces that were cheerful once and familiar only a short time ago, are no more, and the end is not in sight.”

Reagan converted the Kayenta school into a hospital, in which some of the afflicted could be given medical attention. Despite his heroic efforts, he listed nearly 150 fatalities within just a twenty-five-mile radius. The first twenty-one victims on his list are these:

Clazien Begay; male; age, 45; widower.

Eshin Sosies’ wife; age, 30. Four children; ages, 9 years, 4 years, 2 years, 6 months. Husband survived.

Waie; male; age, 30.

Asthon Elseesee; female; age, 40. One child; age, 14 years.

Aosteon Ganeten Begay; male; age, 12.

Aosteon Ganeten Begay; male, age, 8.

Nelthinie Begay; male; age, 4.

Nelthinie Begay; male; age, 5 days.

Kay Bitse; female; age, 42. Five children; ages, 18, 16, 14, 12 and 7 years.

Asthon Hunnagonic Begay; male; age, 16.

Glad Hand; male; age, 26….

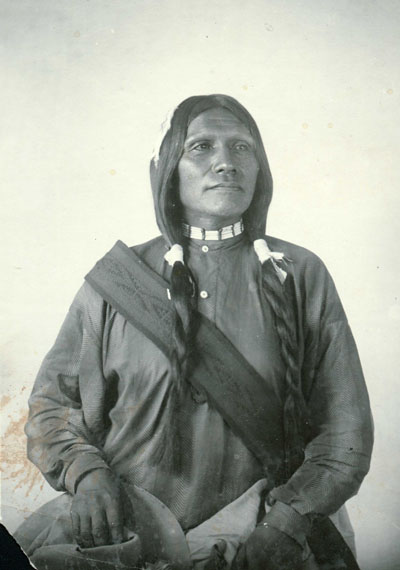

The Wetherills had known Glad Hand from the time they arrived in Utah in 1906. University of Utah professor/archaeologist Byron Cummings hired him as a guide and wrangler on his early forays into the region and explained the origin of his name. “He was a rather peculiar, though very agreeable fellow, always smiling, and always ready to shake hands—a trait that had given him the name of ‘Glad Hand’ among the Navajos and whites alike.” John Wetherill enlisted Glad Hand to help with the livestock on Theodore Roosevelt’s 1913 trip to Rainbow Natural Bridge. (See my article, “The President Slept Here: Theodore Roosevelt’s 1913 Visit to Kayenta and Beyond”, in the August/September 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

John Wetherill was on a hundred-mile horseback journey to Shiprock, New Mexico when he came down with the flu. He consulted a physician at a small settlement that he passed through. “You’ve come too late,” the physician said. But John refused to believe him. He rested two days and continued on. When he reached Shiprock, he transacted his business and, although suffering, turned back toward home. When he arrived in Kayenta, he learned that rest of the family were also down with the disease. Only his business partner, Clyde Colville, and a government engineer who was staying with them remained well.

Some years later, the Wetherills related the story to a University of Arizona student, Frances Gillmor, who recounted the immediate aftermath in her master’s thesis:

Colville took care of them all, cooked for them, milked the cows, and ran the trading post. He opened the doors of the post for just one hour every morning so that the Navajos riding in from the desert could get their supplies.

Every day the People came asking for someone to bury their dead. Colville and the engineer rode out together, sometimes burying three or four at once.

When the Wetherills themselves had recovered they returned to the task of caring for the sick, of burying the dead….

The government school was turned into a hospital, and from Tuba City seventy miles away a physician and nurse came for part of the time. When they were not there, [Louisa Wetherill] was in charge. Dying Navajos begged to hold her hand.

It was necessary to keep each death secret, lest the Navajos, fearing the evil chindi which lurk about a place where there had been death, might get up from their beds and go out into the snow. And in the night John Wetherill and Clyde Colville buried those who had died during the day.

John Wetherill recalled that he helped bury about a hundred of his neighbors. Up north, a range rider from Bluff, R. E. Powell, checked on a Navajo home and found that five of its six occupants had died, with only an eight-year old boy still alive, but emaciated due to lack of food. Powell enlisted two of his friends to help bury the bodies, but they were unsuccessful in convincing the boy to go with them. They summoned John, who spoke Navajo, and he was able to persuade the lad to go with him for help.

The Wetherills received the sad news of the death of the noted Paiute guide, Nasja Begay, his wife, and four of his children. Only one son, a six-year-old, survived. Nasja Begay had led the 1909 expedition that brought the spectacular Rainbow Natural Bridge to the world’s attention, resulting in its designation as a national monument. In 1913, John recruited him to guide the novelist, Zane Grey, on his first trip to the arch, and, later that summer, for the same trek with Theodore Roosevelt.

The pandemic had already ravaged military establishments around the world with a vengeance, striking down young soldiers who were just entering the prime of their lives. The Wetherills received the tragic news that Louisa’s bright, eighteen-year-old nephew, Kipling Wade, formerly of Moab, Utah, had succumbed to the flu. He had the spent the summer of 1914 and part of 1915 at the Wetherill home in Kayenta, so the family knew him well. At the time of his death, he was in the Signal Corps at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. A few months before his demise, he wrote a sweet letter to the editor of the Grand Valley Times:

I received a letter from home today and also the always welcome Grand Valley Times. And as I read the news of the familiar faces and familiar names my thoughts carried me back over the prairies of Kansas, back over the Colorado Rockies, to the little town in southeastern Utah where I spent four of the happiest years of my life…. Army life is wonderful and any boy that enlists will not regret it…. And some day when Old Glory floats triumphantly over the kaiser’s palace in Berlin I hope to come back and make Moab my home.

The physical, emotional, and moral strength of the Wetherills, Clyde Colville, Albert Reagan, and others during this crisis is incomprehensible from today’s perspective. No one forced them to perform their service of mercy or compensated them for it. They were conscientiously driven to help their neighbors—for the afflicted to provide food, medicine, and comfort, and, for the deceased, to dig their graves and move and bury their bodies.

The Navajo people exhibited amazing fortitude, as well, and rebounded with vigor after the ordeal ended. In the years that followed, visitors to the Wetherill home observed local people who were again upbeat, joyful, and respectful of their natural environment. John Collier, who first came to Kayenta in 1923, wrote this of the Navajos: “So poor they are…. Yet the note which their life strikes is exuberance and joy, a winging note and the note of the dance and the dancing star.”

Raymond Don Yellowman, President of the Bodaway-Gap Chapter of the Navajo Nation, recently explained the outlook that has brought his people strength in the midst of natural disasters. “These are acts of God. The Creator brings these things. We, the people who are spiritual, believe there’s a reason for these things. There’s a purpose…. Maybe this is a reminder not to be so reliant on this modern world that we’ve become dependent on.”

The common belief is that people of the modern world have been ascending the evolutionary ladder and achieving a state of enlightenment that was unknown to so-called primitive people, such as the residents of the Kayenta area in 1918. In reality, history shows that the human race has grown weaker and less capable of coping with life’s inevitable hardships as time goes on. One should wonder why an approach to life that has caused human endurance to decay and distress levels to increase is considered progress.

Marc Brackett, the founding director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, recently studied the effects of the current influenza crisis on 5,000 people across the United States. “We are, right now, living in a nation, pretty much a world, where people are highly activated, feeling anxious, feeling like they have no ability to predict what’s going to happen,” he concluded. “They can’t control what’s going to happen and that it might last forever. And it’s really putting our nation in a terrible place regarding their mental health.”

The reason for this heightened level of distress and trauma is not difficult to discern. The prevalent philosophy of modern society is that, through our advanced intelligence, we can and should devise artificial environments to shelter us from all the unpleasantries of nature. “Human providence is more potent than flood, more potent than drought, more potent than wind. The man of intellect wields a power that giants cannot exercise,” wrote the Colorado River runner and philosopher, John Wesley Powell, in the late 1800s. When natural conditions occur that erode the foundations of this fictitious, deeply-seated belief, despair abounds. On the other hand, those who are not trying to escape from nature, such as most of the residents of the Kayenta area in 1918, do not suffer this same effect and are able to face even more serious challenges with courage, strength, and clarity of mind.

Modern people are weak because they have chosen to exchange their innate awe of nature for a lust for artificial contrivances. Seventeenth century English poet and clergyman Thomas Traherne described the point in his childhood at which he made this mistake: “So I began among my play-fellows to prize a drum, a fine coat, a penny, a gilded book, & c., who before never dreamed of any such wealth. Goodly objects to drown all the knowledge of Heaven and Earth! As for the Heavens and the Sun and Stars they disappeared, and were no more unto me than the bare walls. So that the strange riches of man’s invention quite overcame the riches of Nature….”

Some thinkers have traced the impotence of human character to an underlying fear of death. “For behind the sense of insecurity in the face of danger, behind the sense of discouragement and depression, there always lurks the basic fear of death, a fear which undergoes most complex elaborations and manifests itself in many indirect ways,” wrote psychoanalyst Gregory Zilboorg.

In his 1974 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Denial of Death, cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker stated: “the idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else; it is a mainspring of human activity—activity designed largely to avoid the fatality of death, to overcome it by denying in some way that it is the final destiny for man.” According to Becker, individuals and societies create various “immortality projects”, by which they imagine that they are transcendent over nature. The now almost universal belief in “progress”, which might better be named “the cult of artificiality”, is one such project. Becker concluded that the denial of death is a necessary illusion in light of the irreconcilable conflict between our aspirations and the reality of our mortality.

History suggests, however, that the denial of death is not as universal as Becker claimed. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapist Donald Robertson studied the ancient Stoics and learned that a source of their strength in the face of adversity was the acceptance of their inevitable deaths.

We live in denial of the self-evident fact that we all die eventually. The Stoics believed that when we’re confronted with our own mortality, and grasp its implications, that can change our perspective on life quite dramatically. Any one of us could die at any moment. Life doesn’t go on forever. We’re told this was what Marcus [Aurelius] was thinking about on his deathbed. According to one historian, his circle of friends were distraught. Marcus calmly asked why they were weeping for him when, in fact, they should accept both sickness and death as inevitable, part of nature and the common lot of mankind.

In the book, Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth-Century Navajo Shepherd, Louisa Wetherill translated and recorded the remarkable story of her friend and neighbor and the wise teachings of his grandfather that became the source of his strength, optimism, and integrity. His grandfather’s ultimate, most poignant lesson occurred at the end of the story.

One morning he came to me. He looked happy and contented. We talked for a while about things around us. Then he said, “My grandson, I will not be with you much longer. I want you to remember what I have taught you and live your life. I am going on a long journey to the peaceful land at sunrise twenty days after this day.”

“…I am not sorry to go. I have had a full life and have been happy. I know the time will not seem too long before the ones I am leaving behind will go to me. I will miss all of you for a while, but I know the time is almost here for me to go, and I am glad I know just when it will be. I am not sad about it, my grandson, and I do not want you to grieve for me anymore than you can help. Just think how much better it is for me to go now while I am still strong than it would be if it was my lot to stay here until I was so old that I would be helpless.”

…We sat out in front of the hogan and Grandfather talked to the family until the middle of the night. Then he said he wanted to sleep where he could see the stars and the moon this last night. As soon he lay down, he went to sleep, but I did not sleep. I lay by his side and watched him until the dawn came. Then he sat up and watched the dawn with me. Just before the sun came, he lay down again.

Just as the sun came over the mountains, he said, “Goodbye, my children. I must be going now.”

We all began to grieve for him when he stopped breathing.

Wolfkiller took his grandfather’s teachings to heart. He stayed connected with nature and continually learned from it. Like his grandfather, the strength he gained from this approach allowed him to face his mortality without fear. Louisa Wetherill recalled his last day. “One day he brought the sheep back to the corral in the late afternoon. An hour later, he was gone. He died as he had lived—quietly and in peace with the world.”

What history teaches, then, is that nature is the source of strength in the face of adversity, even when nature is the source of the adversity. Those who are wise do not attribute evil to nature. They do not worry about things they cannot change, but deal with situations as they arise to the best of their abilities. They avoid compromising their integrity for the sake of comfort or pleasure. And they take comfort in the big picture by observing the power and consistency of nature—the sun, moon, and stars, seasons, plants and animals, and life’s cycles of birth and death.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Beaufiful article full of wisdom for the ages.

Another well documented and excellent story about American wisdom and its’ beautiful wilderness from Harvey!

Thank you, Harvey, for a beautiful and timely story. My father, Julian, read the original manuscript that Louisa wrote of Wolfkiller’s life, and remarked on that very passage you quote–“I want to live, and die, like that.” He did just that. I am forever grateful that he steered me towards Navajo country at an early age.

Harvey and his words are medicine for my soul. He recommended the Becker book to me years ago, and I purchased it and read it. But Harvey, Wolfkiller, and the Wetherills give me courage to face death by their example. It is comforting to know that in spite of all the evil we see today, that there were, and still are, kind and caring people like Harvey and the Wetherill family.