The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market.

— Adam Smith

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere.

— Karl Marx

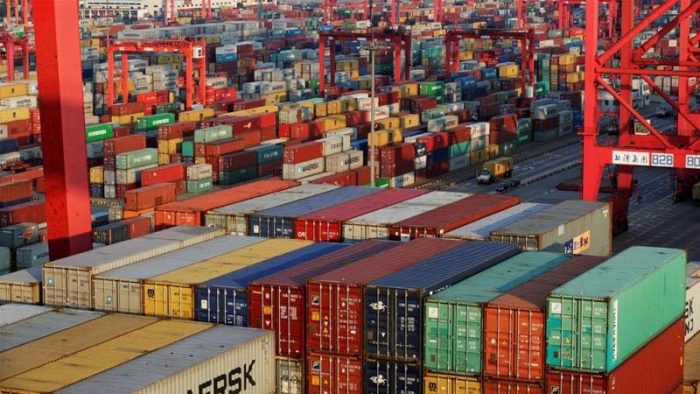

Among its many effects, the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare many of the consequences of the single-minded pursuit of economic efficiency. It is common knowledge that much of the economy has been radically transformed over the past several decades, and yet I suspect many of us have nevertheless found it a bit breathtaking to learn just how complex and brittle global supply chains have become. Let’s briefly review how we got here.

An economics predicated on growth by definition requires a constantly expanding market. In practice, this often resembles Matt Taibbi’s memorable description of Goldman Sachs as a “great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” In more arid terms, market liberalization and the development of numerous technologies have enabled the extent of the market available to large multinational corporations (MNCs) to become immense.

The corollary is that the potential for the division of labor is now similarly immense. Large modern MNCs have become de facto arbitrageurs: firms can now relatively easily detach each discrete part of their business model from the whole and locate it in whatever place holds a comparative advantage for that particular activity. Functions like management and R&D tend to be located in certain (wealthy) nations where they can cluster with research universities, well-developed capital markets, and large law and accounting firms. Cost centers — think manufacturing and tax residence — tend to get located elsewhere for their own obvious reasons.

The seemingly infinite potential for the division of labor is not constrained by the boundary of the firm either. Indeed, many “old economy” firms have turned themselves into shells containing little more than the marketing function, relying on a Rube Goldbergian array of contractual relationships to facilitate the outsourcing of nearly all the productive activity that advances the brand’s agenda. Virtually no startup aspires to anything other than this sort of arrangement. Adam Smith’s pin factory could hardly seem more quaint in comparison.

The pursuit of these sorts of efficiency-maximizing strategies has relentlessly, systematically squeezed costs out of one production process after another. This has led, in turn, to soaring corporate profits and a significant drop in real consumer prices in many product categories. Enormous, high-definition TVs, for example, have become radically cheaper as advanced technologies trickle down to low-cost Asian manufacturers (and as production costs are subsidized by the income potential of incorporating Smart TVs into surveillance capitalism’s substructure).

Unfortunately, when supply chains are extremely long and attenuated, as many now are, they become vulnerable to total breakdown from many different threats that may strike in any one of many different places. Whether it is an extreme weather event here, a political crisis there, or a communicable disease anywhere, any single “Swan Event” now holds the potential to turn a local emergency into a global catastrophe. It turns out, in short, that resilience has been sacrificed at the altar of economic efficiency.

Many American households find themselves in an analogous trap. The ideal of the successful contemporary American household consists of two high-earning professionals who sell their specialized expertise on the labor market and then purchase, also on the market, the vast majority of the products and services necessary to sustain their household. The home occupied by our affluent-but-time-crunched professionals was likely built not by a small number of general craftspeople, but by a coordinated corporate orchestra of subcontractors specializing in just one narrow part of the construction process. Maintenance of the finished home may well be handled by a platoon of handymen, cleaners, pest abatement providers, dog walkers and swimming pool caretakers. Much of the food consumed by our heroes is either plucked from an elaborately-sourced supermarket, delivered by Blue Apron, or prepared by a restaurant. Virtually all other categories of consumer goods in this hypothetical household are likewise the product of the work of a dizzying array of far-flung specialists, and even the care of any children in the household may also be outsourced in significant part.

It all hums along quite nicely for all involved as long as nothing goes amiss, but look closely and you can observe that such a household has itself become, in effect, an extremely “thin” economy, comparable to an underdeveloped, resource-cursed OPEC nation which stakes virtually all of its fortunes on a single export commodity and relies heavily on imports to round out the supply side of its economy. The entire arrangement rests on a razor’s edge.

This is radically different from conditions not many generations ago, when the typical American household operated at a scale and scope that permitted it to autonomously sustain at least a subsistence standard of living. The food that made up the typical diet was grown or raised close by — often very close by — and clothing and shelter was likewise fashioned independently or by local craftspeople from readily available materials. In more modern times, this arrangement was quite heavily mediated by market transactions, but the practical extent of most markets was much smaller and, by extension, the degree of specialization was also much more limited.

Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.

— Milton Friedman

If we can agree that the pandemic has revealed aspects of our society and economy that were previously only dimly understood or completely submerged, and if we can agree that what has been uncovered includes a good deal of malign dysfunction, what comes next? Given our existing political power structure, the prevailing ideas that have been lying around nearly unchallenged for roughly 40 years, and the actual policy response so far, my money is on yet another new stage of mutant neoliberalism.

But there are other ideas lying around that could be dusted off and applied to the problems of now. In particular, a few lonely voices are revisiting similar or adjacent concepts like autarky, economic nationalism, self-sufficiency, deglobalization, decoupling, and delinking. All of these similar or adjacent ideas argue for an unwinding of at least some of the existing globalized, efficiency-maximizing paradigm in favor of economic models that take into account other social and economic values and which, as a consequence, tend to favor more localized economies and markets which are smaller and less specialized, but also more resilient. It may bear noting that these happen to be concepts which are not easily reduced to unhelpful left-right categorization. Indeed, there have been both left and right variants of these ideas observable across history.

It is frequently noted that if there is anything positive about this unique moment in history it is that it has presented the opportunity to consider, as individuals or as a society, whether there are alternative ways of living that make more sense than the status quo ante. In that spirit, I offer a thought experiment on which a local model of self-sufficiency might be loosely based: New York’s Adirondack Park.

What if, instead of provoking lovers of public lands (of all political persuasion) with blunt land transfer agitation based on tenuous legal arguments, Utah’s political class instead made a case for local governance on principled social, economic and conservationist grounds? What if, instead of offering little more than “trust us” when it comes to the future of hypothetically transferred federal lands, Utah instead first developed, say, a coherent and thorough framework for how they (we) would actually care for all of the canyon country south of I-70 and east of I-15 as a singular region comprising both public and private land and the people who occupy it?

If you allow yourself a moment of utopian fantasy along such lines, you can fairly quickly begin to see how such a framework might contain the potential for building a “New Western Economy” and reversing some of the alienating and destructive tendencies of our existing economic and environmentalistic mental models. I picture a modest proposal that would ensure large, important tracts of canyon country are preserved intact in perpetuity; rationalize economic activity across the region to encourage regional self-sufficiency and discourage the strip mining of the landscape for export, whether by heavy industry or Big Rec; and prioritize principles of self-determination in the creation of novel structures of governance.

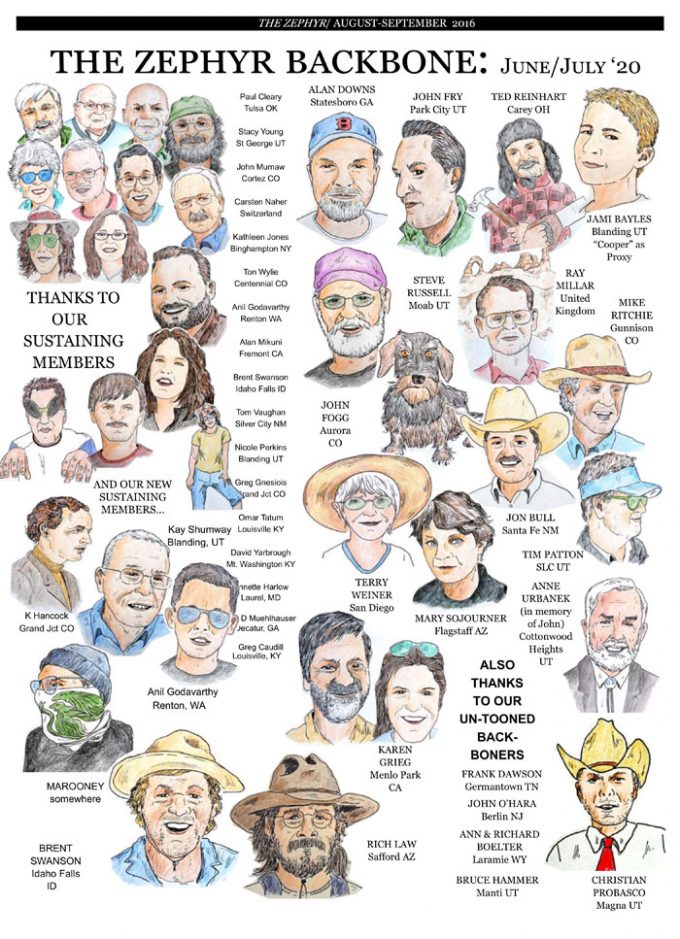

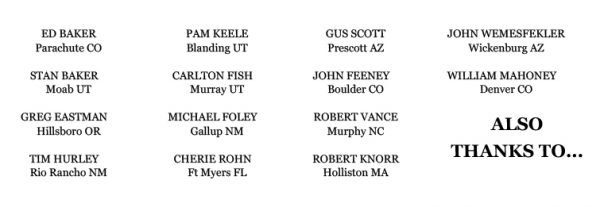

Stacy Young is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in Southwest Utah.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

One of the other things the pandemic is making us think hard about is federalism. Environmentalists have relied on the Federal agencies and courts to protect the air, water, and land in ways that would never have happened at the State or local levels. But now, a disastrously failed Federal response to both the pandemic and to an outrageous expression of systemic racism, are making us think about what the states and cities can do. May have to do.

Writing from the heart of the Adirondacks, I am bemused by Stacy’s proposal of the Adirondack Park as a model. It is, but one must be very careful in saying exactly how The impulse for the preservation of these amazing mountains as “forever wild” (that’s what the State Constitution requires) has resulted in a healthy landscape in which people who accept certain limitations, including the near certainty of a lower income, can enjoy a great quality of life. This has been accomplished both through the management of the public lands for wildness and the stringent regulation of private lands. And interestingly, it has led, though over many decades, to an increasingly robust regional economy. While toilet paper did run short here in March, we never worried about the meat supply chain. Ours is only about 50 miles long and held up beautifully as the producers switched to a drive-through farmer’s market. Vegetables are hard in this climate’s dreary spring, but we had those, too.

The Adirondack Park is not a land of unusual harmony. There is continuing controversy and awkward compromises (how do you stage the Olympics on land where you need a Constitutional amendment to remove trees?) have been needed. Not all local folks benefit equally. The issue of short term rentals has recently wrecked social and political havoc in Lake Placid and affordable housing that is close to jobs is virtually non-existent here. Good jobs go unfilled because of the housing shortage. Cell service is uneven (and that leads to land use controversy, too). Likewise, internet access.

It should also be understood that Industrial Tourism is here, in a form at least as challenging as southern Utah’s. The Adirondacks are within an easy day’s drive of Toronto, Montreal, Boston, and New York City. And the state is, in my observation at least, even less adept at managing the impacts of tourism than the Federal agencies. This will get way too long if I expand on that.

The Adirondack Park exists because of an amendment to the New York Constitution that was adopted before Utah became a state and because of the foresight of the state’s urban majority during the environmental “revolution” of the early 1970s. The blue line (the term used for the Park’s boundary) and management within it was imposed on local folks (though there were supporters among them) by an urban and suburban elite and there should be no illusion that the state’s land managers are any more popular than Federal land managers.

Could there be a 2020s version of the Adirondack Park in southern Utah? I am tempted to just say “no.” But I do not want to rain on Stacy’s parade without acknowledging its hopefulness. And the State and even local governments in southern Utah do have the rare sensible moment. But those moments have always been overwhelmed by the dominant ideology.

And that’s what would have to be re-framed and encouraged to evolve in a new direction. It has taken me a long time to see this, but its not capitalism or even its ugly neo-liberal upshot that is the issue . It is the underlying “ism,” individualism that drives things in rural America. That and the dissonance that comes from trying to live the myth of individualism in a reality of almost abject dependence on outside forces. The people of southern Utah could ask themselves if they want to escape that dissonance and draw their own line (the red rock line?). Doing so would be unprecedented. It would require heroic honesty and effort. I’d love to see it.

Great article–it’s not always easy to discuss economics in such clear terms. Thanks for the thought experiment!