In the months after Herb Ringer’s 1941 move to Reno from New Jersey, he set out to explore the barren deserts nearby. Even before the war, much of the American West was relatively empty, and towns in the Great Basin of Nevada, were few and far between. Boom towns, born in the early 20th Century for their mineral potential, had gone bust decades before and were sparsely populated. Now, with Pearl Harbor, the West felt abandoned. Herb took it upon himself to make sure these lonely ghost towns weren’t completely forgotten. And he did find a few souls hanging on to the past.

One of Herb’s favorite “ghost towns” was Rhyolite, Nevada, just east of Death Valley. Here is a brief Wikipedia description:

Rhyolite is a ghost town in Nye County, in the U.S. state of Nevada. It is in the Bullfrog Hills, about 120 miles (190 km) northwest of Las Vegas, near the eastern boundary of Death Valley National Park. The town began in early 1905 as one of several mining camps that sprang up after a prospecting discovery in the surrounding hills. During an ensuing gold rush, thousands of gold-seekers, developers, miners and service providers flocked to the Bullfrog Mining District. Many settled in Rhyolite, which lay in a sheltered desert basin near the region’s biggest producer, the Montgomery Shoshone Mine.

Industrialist Charles M. Schwab bought the Montgomery Shoshone Mine in 1906 and invested heavily in infrastructure, including piped water, electric lines and railroad transportation, that served the town as well as the mine. By 1907, Rhyolite had electric lights, water mains, telephones, newspapers, a hospital, a school, an opera house, and a stock exchange. Published estimates of the town’s peak population vary widely, but scholarly sources generally place it in a range between 3,500 and 5,000 in 1907–08.

Rhyolite declined almost as rapidly as it rose. After the richest ore was exhausted, production fell. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the financial panic of 1907 made it more difficult to raise development capital. In 1908, investors in the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, concerned that it was overvalued, ordered an independent study. When the study’s findings proved unfavorable, the company’s stock value crashed, further restricting funding. By the end of 1910, the mine was operating at a loss, and it closed in 1911. By this time, many out-of-work miners had moved elsewhere, and Rhyolite’s population dropped well below 1,000. By 1920, it was close to zero.

In a 1989 letter, Herb told sent me some black and white photographs of Rhyolite and included a wonderful account of his own experience in Rhyolite:

Dear Jim,

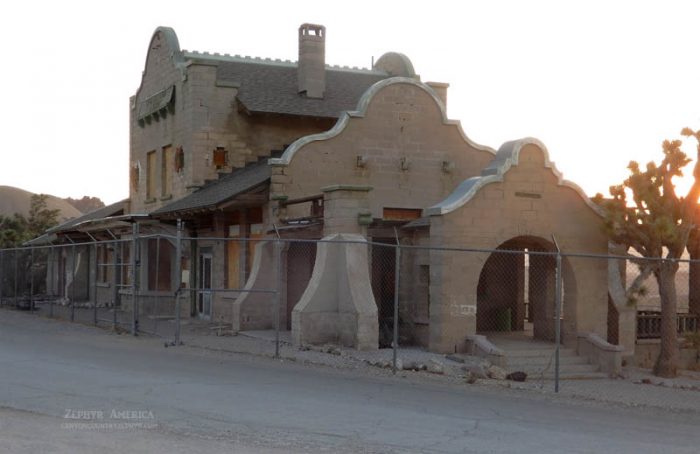

Just a little explanation on these old prints. Wes Moreland, standing in the doorway of the railroad station at Ryolite with his red setter. Both lived quite well on steak every day. I believe he remarked that Wes had a local Indian that supplied him with beef. “A long rope, a fast horse and a runnin’ iron were the necessary tools of the trade.”

In a land even now remarkably free of human occupation, one can ride horseback great distances without being encountered with the meeting of other humans.

Wes, for some reason, took a liking to me, and I in turn found him one of the most fascinating desert people I had the privilege of meeting. During the second world war years he was one of a few inhabitants at Rhyolite. He kept a well-stocked bar but, as a diabetic, refrained from indulging. It was Wes, you will recall, who ate live ants, prescribed by a Shoshone woman living in an old box car as treatment for his tuberculosis.

He expired at least 40 years ago.

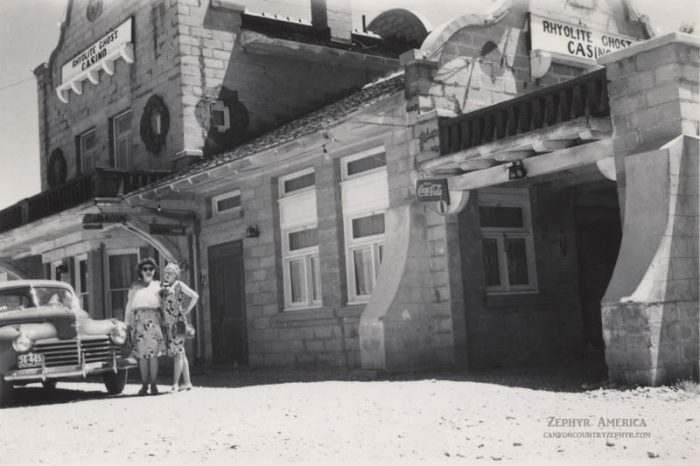

Regarding the two “ladies of the night.” These gals picked me up as I walked across the desert between Beatty and Rhyolite. They formerly lived and entertained in the upper rooms of Wes’ depot. They were utterly polite and I had not seriously contemplated their occupation nor their desire to visit Rhyolite. When we arrived, they embraced Wes and it appeared a familiar gathering of kindred spirits.

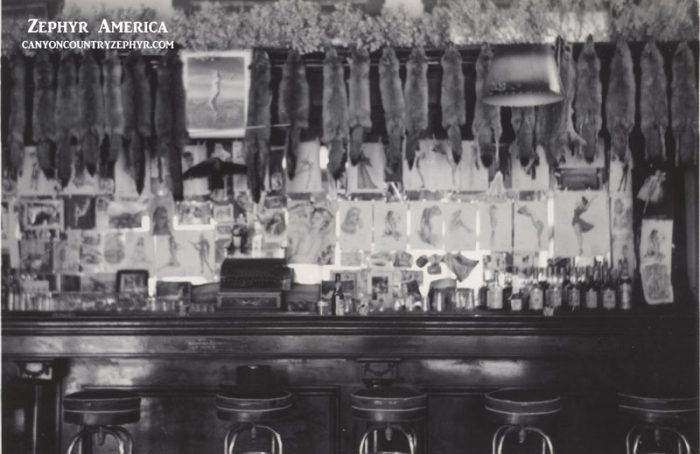

As for the interior of the Rhyolite bar. Wes was infamously famous for his collection of photos of nudes and near-nudes. The walls were covered with a glamorous array of these women.

Above the bar, toward the left and amid all the coyote skins is a large framed nude of particular interest. This was the daughter of Harriman, money-bag of great repute and president of the New York Central railroad. The gal had a flare for crashing elite parties in Hollywood clad only in a mink coat.

When Wes expired, the Depot and accoutrements all reverted to two maiden aunts in Georgia. When they arrived at Rhyolite and were ushered into the precincts of Wes’ bar and beheld his girls, they promptly fell dead.

Your friend, Herb

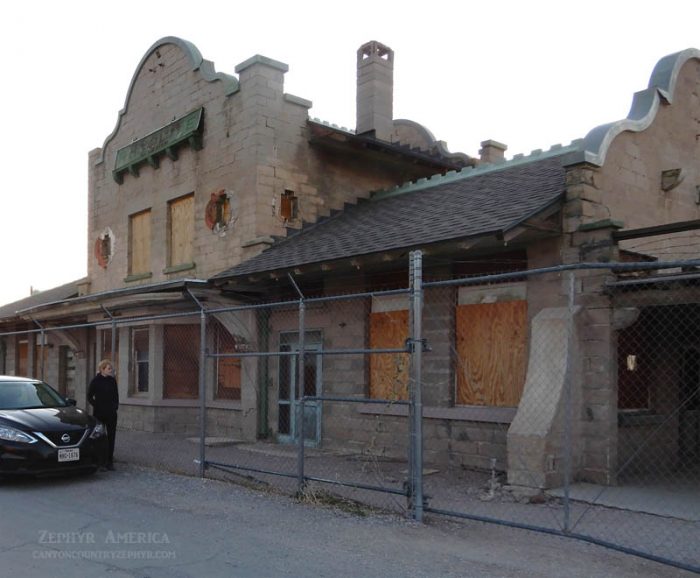

Last October, as Tonya and I returned to Nevada, in pursuit of Herb’s old stomping grounds, we eventually found our way to Rhyolite, and nearby Beatty. The little town remains a ghostly remembrance of the past. With Herb’s old 1941 photos to guide us, we found that many of the old buildings are still standing, though it’s clear they have deteriorated considerably in the last 80 years.

The depot is vacant and a chain link fence has been constructed around its perimeter to keep out vandals. No sign of Wes or those “ladies of the evening.”

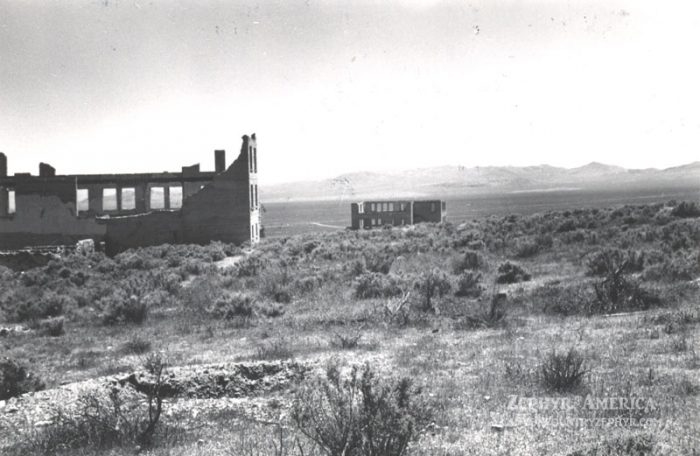

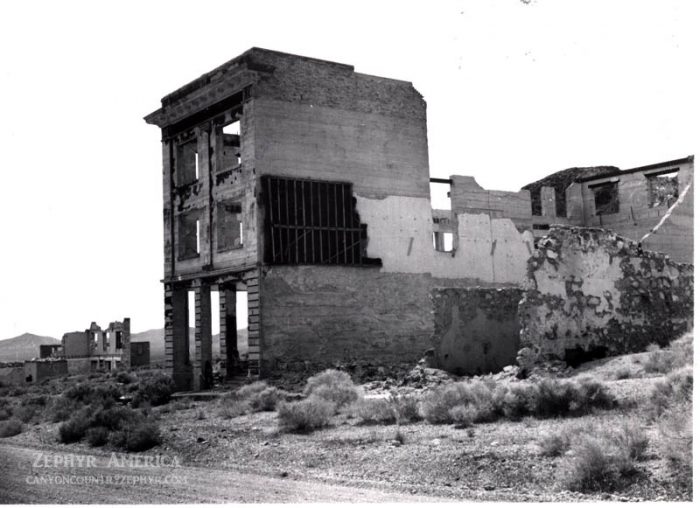

The old bank building still stands, though more of the walls have collapsed since Herb’s early images.

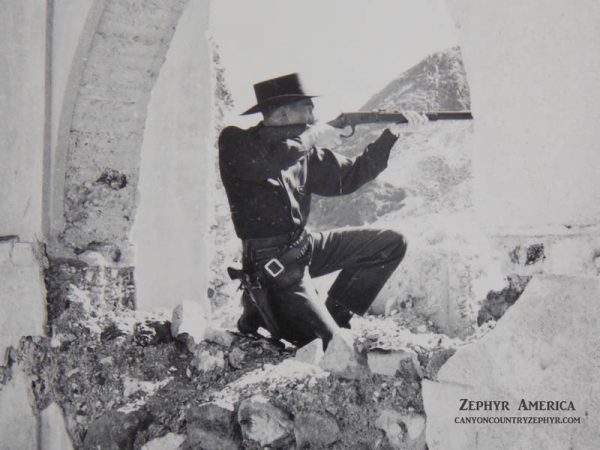

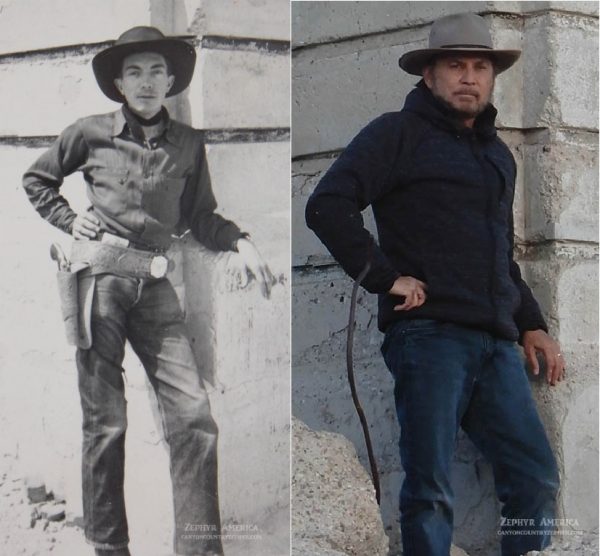

Herb posed for his father at the corner of the bank, fully armed and bedecked in one of his extraordinary “Western duds.” I tried to fill in, as best I could.

And the nearby “bottle” house…

Later we drove back to Beatty and found the old Mercantile building that Herb recorded in 1941. The building stands but has been “modernized,” much to its own detriment.

And then there is this. For comparison, note the desert hills in the distance. Same scene. Different world. We prefer 1941.

–JS & TS

Read the previous installments of “On Herb Ringer’s Trail” at these links:

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

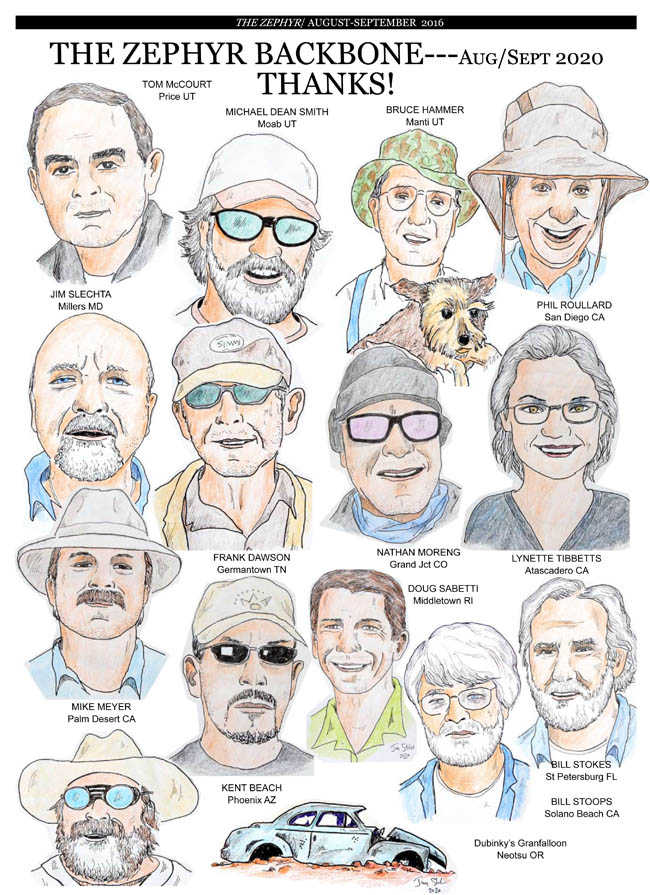

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Love those before and after pictures… did anybody photograph Cisco, UT, before it was a ‘ghost’ town? And now that maybe it isn’t such a ghost town after all…