My great grandparents, John and Louisa Wetherill, left a legacy that includes thousands of historic photographs they collected down through the years and preserved to pass on to future generations. These images, along with textual records, have been invaluable in helping unravel the stories of interesting pack trips into the canyon country that John guided, photos of expedition participants, and locations of historic campsites and abandoned trails for which no known maps exist.

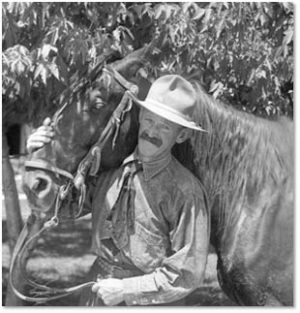

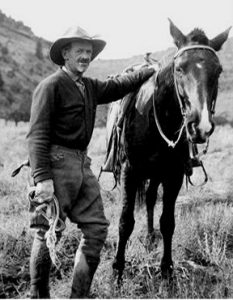

In their first published personnel roster for the year 1918, the National Park Service reported just thirty-two staff members nationwide. Included were thirteen custodians of national monuments, many of whom had volunteered to serve under the General Land Office years earlier. In the rugged country in northern Arizona, just south of the Utah border, John Wetherill, was listed as custodian of Navajo National Monument, a position he had held since its creation in 1909. He was also the de facto custodian of Rainbow Bridge National Monument. Besides his official duties, Wetherill was an Indian trader, explorer, outfitter, guide, and host to adventurers who made their way to his remote outpost near Monument Valley. From there he would take visitors by pack train on long camping trips to the national monuments and other points of interest.

John Wetherill and his wife, Louisa, were from Mancos, Colorado, where their families settled in about 1880. The Wetherills were of Quaker heritage, which gave them a decidedly different view of the rugged Four Corners country, Native Americans, and modern society than most of their neighbors. John and his brothers are known for their involvement with the early exploration and investigation of Mesa Verde long before it was designated a national park.

In 1900, John, Louisa, and their two young children left Colorado for the Navajo country of New Mexico to manage the Ojo Alamo Trading Post. In about 1905 they relocated to Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, then, in 1906, desiring to live among Indians who had not been influenced by outsiders, they moved to Oljato (Moonlight Water), Utah, west of Monument Valley. There they began a new chapter in their lives that was to last until their deaths in the mid-1940s. In December, 1910, the family moved about twenty miles south across the Arizona border to a place they called Kayenta. Down through the years, as their home became a gracious lodge, they had the opportunity to interact with thousands of people—Indian neighbors and visitors from around the world.

In 1909, the U. S. General Land Office proposed designation of a preserve to encompass the archaeological treasures in the area west of Kayenta, and Wetherill volunteered to serve as Custodian of the newly-created Navajo National Monument—a role he fulfilled for nearly thirty years. He also helped outfit and guide the expedition that arrived at Rainbow Bridge on August 14, 1909 and brought its existence to the attention of the world. Despite its remoteness, the U. S. General Land Office recommended that Rainbow Bridge be designated as a national monument, which Wetherill considered his responsibility to watch over, as well.

Of the handful of early non-native visitors to Rainbow Bridge, most all were taken there by Wetherill. The trek started at the trading post and involved a horseback ride of some seventy miles each way, over a route that traversed, in some sections, terrain that was seemingly impassible. Most often, the treks would include a stop at the cliff dwellings of Navajo National Monument. Some of the more intrepid explorers also asked Wetherill to include the distant Grand Canyon National Monument in their itinerary.

1.The 1909 Expedition to Rainbow Natural Bridge

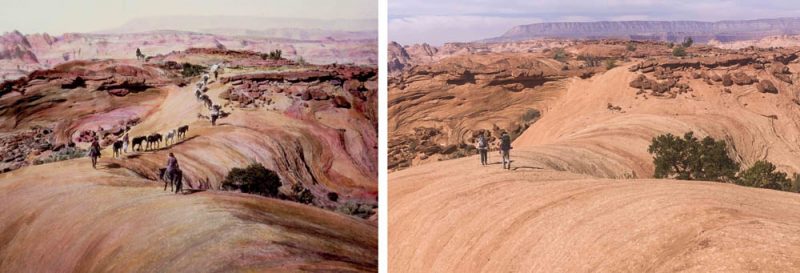

Wetherill was one of the fourteen members of the famous expedition to the incomparable Rainbow Natural Bridge in 1909. Many of the participants documented their experiences in journals and other accounts, but the photographic record reveals exceptional scenes that are not found along the modern-day hiking trail. The most significant route change is north of Navajo Mountain where a Civilian Conservation Corps team blasted a new trail into Baldrock Canyon in 1933, bypassing a particularly scenic and precarious section of the original route. I was first told about this “lost” section of the trail by my mentor and friend, Stan Jones (“Mr. Lake Powell”), who kindly introduced me to the amazing Rainbow Bridge trail in 1979.

A few years later, in the absence of maps, Stan and I set out with Wetherill photographs in the hopes of relocating the abandoned trail segment. Our destination was some particularly convoluted country between Cha and Baldrock Canyons, several miles north of the current hiking trail. On our first attempt, we knew we were in the general area, but we were unable to match the views in the photos. On our second excursion, some of the old scenes suddenly came into alignment, and we knew we had found what we were looking for. The original crossing between the two canyons was as stunning, beautiful, and precarious as the old-timers had described it.

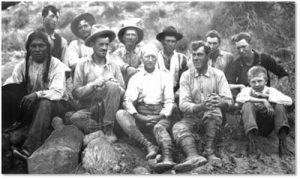

One of the images in the Wetherill collection is a well-known group photograph taken at Rainbow Bridge that portrays eleven of the fourteen members of the 1909 expedition. Two of the other three participants were photographed individually—the photographer, Stuart Young, and Navajo wrangler Dogeye Begay. Not included in any of the 1909 images, however, is the young Paiute man, Nasja Begay, who served the key role of guiding the group through the labyrinth of canyons on the final leg of their journey. He also guided Zane Grey to the arch on his 1913 visit and Theodore Roosevelt on the same excursion a few months later. Rainbow Bridge historians were long interested in finding a photograph of him.

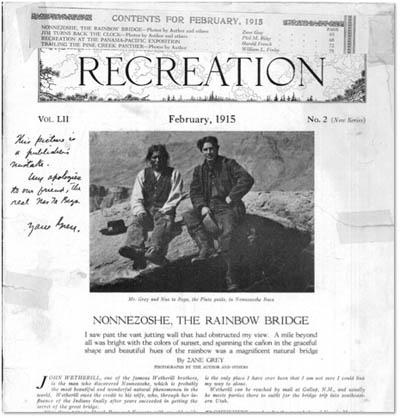

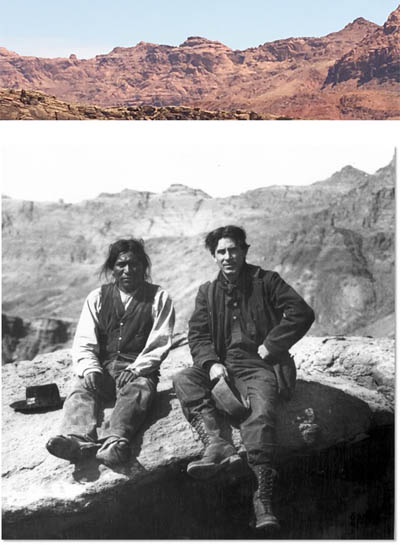

Grey published an account of his trip in a 1915 Recreation Magazine article entitled “Nonnezoshe, The Rainbow Bridge.” It includes a photograph of Zane Grey and a Native American man that is captioned: “Mr. Grey and Nas ta Bega, the Piute guide, in Nonnezoshe Boko [Rainbow Bridge Canyon].” When the word got out to researchers that this purported photograph of Nasja Begay existed, it was republished in several books and represented as being an authentic photograph of the guide. However, the accuracy of the caption was suspect for a few reasons. The strata in the background does not match the geology of Rainbow Bridge Canyon, and Zane Grey appears younger than he looked in 1913. The clincher, however, is a hand-written note in a copy of the article that states: “This picture is a publisher’s mistake. My apologies to our friend, the real Nas Ta Bega. [signed] Zane Grey.”

The question still remained, then, whether an authentic photograph existed of Nasja Begay, and a new question arose: who is the man sitting next to Zane Grey in the published photo? One day I was driving across the Colorado River bridge at Marble Canyon, Arizona, when I glanced in my rearview mirror and saw a skyline that reminded me of the one in a higher-quality version of the misidentified photo. I made a U-turn and saw, to the north of Lees Ferry, the unmistakable outline of the ridge in the photograph. According to Zane Grey historians, Grey was only in that area in 1907 and 1908 when he crossed the Colorado River on the ferry on his trips to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Which of the two years the photograph was taken, the identity of the Native American man, the exact location of the rock on which they are sitting, and why Grey allowed it to be captioned in error are questions that still linger. However, this research established, with certainty, that the photo does not depict Nasja Begay.

The Wetherill photograph collection includes a number of images from the 1913 Roosevelt trip to Rainbow Bridge. Two of the photos were taken at one of his campsites, but they are not marked as to its location. In one of them, a view through the trees shows part of a mesa with vegetation on top, which suggested Segazlin Mesa east of Navajo Mountain. A reconnaissance of the area confirmed the exact location of a site near there in a shallow, nondescript drainage. A large, water-filled pothole confirmed its suitability as a good place to camp. Nasja Begay’s home was in Paiute Canyon, which is not far away. In the second view at the same location, Theodore Roosevelt is standing with three Native American men. One of those men also appears in another photo that depicts some of the party traversing the Rainbow Trail. He is seen leading the way across a precarious ledge ahead of TR. Since Roosevelt had no other native guides, these are most certainly photos of “the real” Nasja Begay. Thus, the photographic record of the participants in the 1909 Rainbow Bridge expedition is now complete.

Now knowing what Nasja Begay looked like, researchers reviewing the massive Zane Grey archives at Brigham Young University were able to identify him with the famous author in several other photographs. Why Grey did not use one of those images in his Recreation Magazine article, rather than the phony one, remains a mystery.

2.The 1909 Townsend Expedition

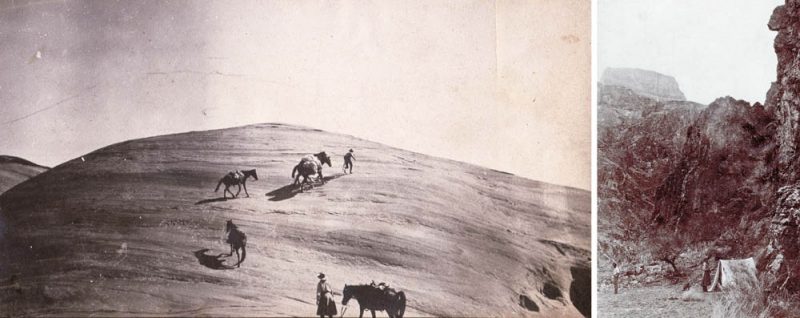

Among the John Wetherill photograph collection is a small album that contains several photos from the 1909 Byron Cummings expedition to the Navajo country. Cummings was a professor from the University of Utah, and he, his son, and three of his students were participants in the 1909 Rainbow Bridge expedition. The album also contains several images from a different expedition. A photograph of a pack train ascending a slickrock dome includes a woman wearing a dress. A camp scene depicts what appears to be the same woman at the bottom of the Grand Canyon with John Wetherill.

The photographer of this series of images is identified in Herbert Gregory’s Geology of the Navajo Country, which includes a reproduction of one of the same Rainbow Bridge photographs. Gregory attributes the photo to “A. R. Townsend”. According to an entry in the Bass Hotel register, New Yorkers Arthur Rodman Townsend and Eleanor Rodman Townsend were at the Grand Canyon with John Wetherill on September 3, 1909. Eleanor was Arthur’s sister. Wetherill must have travelled quickly to leave Rainbow Bridge shortly after his August 14 arrival there, return home, refresh his outfit, and travel by horseback the long distance to the Grand Canyon to meet the Townsends in early September.

The location of the scene in the Grand Canyon photograph was a mystery for a number of years until investigators identified the site on the south bank of the Colorado River just below the old cable car crossing near Phantom Ranch (the current site of the Black Bridge). In 1909, access to the river from the south was via the Cable Trail, which descended from the Tonto Platform east of the more recent South Kaibab Trail.

The Townsends must have altered their Grand Canyon itinerary to also include the long journey to the newly-known-about Rainbow Bridge based on Wetherill’s glowing reports of its majesty. The difficulty of that portion of the trip would have been immense for the New Yorkers, because it was a long distance to ride horses (150 miles from the Grand Canyon to Kayenta and 70 miles from Kayenta to Rainbow Bridge), and Wetherill had no time to build trails through the rough areas leading to the bridge. It is to Arthur and Eleanor Townsend’s great credit that they made the trek, apparently in good spirits, as the first tourists to visit what would soon be designated as Rainbow Bridge National Monument.

3.The 1912 Chanler Expedition

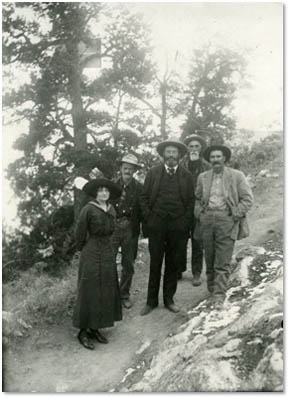

Among the Wetherill photographs is an early Kolb Brothers image of a group of people at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The visitors are identified on the back as “Bob Chandler; Jest Thompkins; John Wetherill; Bert Himand; and New Y. girl.” Despite some misspellings, we can conclude that, besides Wetherill, two of the subjects were Justus Tompkins, who was John Wetherill’s uncle, and Bert Hindman, who was a friend of the Wetherills from Mancos, Colorado. But who were “Bob Chandler” and “New Y. girl”?

Another Kolb photo of the tall gentleman is inscribed: “Robert Chanler; El Tovar; 1912 30th of Nov; Thanks for a great trip.” An article in the Coconino Sun reveals that Robert Chanler was “Ex-Sheriff Robert Winthrop Chanler of New York, millionaire, divorced husband of Lina Cavaleri, the famous prima donna, grandson of John Jacob Astor and rural painter.” He was one of the eight “Astor orphans” who were raised in a mansion by nannies and family members and who each inherited a fortune.

Like the Townsends, the Chanler party visited both the Grand Canyon and Rainbow Bridge. The register that John Wetherill kept at the bridge records: “Oct 1912, Bob Chanler, Fighting Bob, Dutchess Co. NY,” and includes the puzzling notation: “Who is luny now.”

After the Chanler orphans reached adulthood, some of the siblings had their older brother, John, committed to a mental institution. John eventually escaped and was then declared sane. Our subject, younger brother Robert, divorced his first wife and fell in love with a beautiful Italian opera singer, Lina Cavalieri. He convinced Miss Cavalieri to marry him, but she insisted that the nuptial agreement include signing over a large portion of his fortune to her. Bob agreed, they were married in 1910, and Lina promptly left him. His older brother John sent Bob a telegram with the phrase, “Who’s Loony Now?” He also notified the newspapers, and the words that he had directed toward the famous visitor to the Grand Canyon and Rainbow Bridge became a popular catchphrase.

As for the New York girl, the Coconino Sun identified her as Robert Chanler’s wife. However, there is no record of Robert remarrying after his second divorce. Recent research has identified his female companion as Clemence Randolph, a New York actress and playwright.

These are just a few examples of ways that the historic photographs have helped tell interesting stories about the early travels into the canyon country of John Wetherill and the people he guided. Besides outfitting and guiding strenuous pack trips to the national monuments, Wetherill spread the word that the wild country the travelers encountered along the way and the enduring Native American connection with the surrounding landscape holds a message of profound importance to modern people who were otherwise taught that untamed nature is something to avoid. Historic photographs have proven to be invaluable aids in helping us understand the enlightening effects the early journeys had on the pioneer visitors, and they can provide evidence of the value of unimpaired scenery for the present and the future.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Enjoying the family history. Learning the adventurous times.

Very interesting article. Great history. Thanks

Oh if someone would put those photographs in a book I would be the first to buy it!

Great article, Harvey! When is the book coming out>

Immensely interesting. As others have said, I really would hope that this incredible photographic archive be documented in a book form or on-line archive. It is so valuable and interesting to many of us.

Thanks for publishing this.

I had never heard that John and Louisa were briefly resident at Chaco Canyon with Richard and Marietta, before going to Oljato.

Tom – please read the book Traders to the Navajo, about the history of the Wade and Wetherill families.