I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower — and I don’t.

–Georgia O’Keeffe The Poetry of Things

There are mornings that sometimes become an effort of trying to find a way in. This can happen with reading or with staring out of a window. This can happen with making coffee and giving attention to how you make the coffee—how you swirl water in the pot and rinse it out and how you fill the pot with fresh, cold water and how you pour the water into the maker and set the filter in the bail. You measure the grounds with your eyes, as you pour them into the filter. Then you close the lid and push the start button at the base of the maker. A red light comes on. You could walk away at this point, as I do, but you might listen for the first gurgles of hot water, as it runs through the maker and seeps through the grounds and drips into the pot. That’s when you feel life is okay. It’s started, at least. The coffee pot is working. There will be coffee soon. You can smell coffee filling the kitchen. That’s when you go back to a book or window or whatever you need to find a way in, if you haven’t already.

Outside of my living room window, the one from which I can almost see the road that passes in front of our house, is a narrow strip of land between the house and the guardrail. On the other side of the guardrail, of course, is the road. Across the road and into the hills, there are wildflowers. There are small yellow flowers that resemble primroses. There are lavender colored flowers that grow on greenish-purple stems. There are stalky plants with tiny white flowers that resemble Queen Anne’s Lace. And there are lupins, which for me, is one of the most beautiful of all the flowering plants.

Since I didn’t know the name of these flowers, beside the lupins, I wrote to my friend Ragnhild. If I have a flower, mushroom, or edible plant that I don’t recognize, I ask Ragnhild. If Ragnhild doesn’t know about said plant, flower, or mushroom, she will graciously admit she doesn’t know, which makes her pretty fantastic and keeps me from poisoning myself. The small yellow flowers are Caltha Palustris, Bekkeblom in Norwegian or Marsh Marigold in English. I like the word, Bekkeblom. A bekk in Norwegian means stream. I’ve heard the word “beck” used in the U.K., as well, which indicates a tiny stream and often a fishing stream. Blom is Norwegian for flower. The lavender coloured flowers are Geranium Sylvaticum, Skogstorknebb or Wood Crane’s Bill. Sylvaticum from the Latin means “of the forests,” which is too lovely not to mention. Skog is “forest” in Norwegian, and storknebb is “stork beak.” The white flowers, according to Ragnhild, are, “Mostly hundejeks, Anthriscus sylvestric. It can be mistaken for giftkjeks, Conium maculatum, which is highly poisonous.” This offers all kinds of play, given that hundejeks, means “dog biscuits,” and giftkjeks means “married biscuits.” The “married biscuits” are hemlock—yes, that hemlock—and, true to Socrates, they are utterly poisonous.

There are dandelions, vanlig løvetann in the Norwegian, which means “common lion’s tooth.” I’ve been minding dandelions lately. A couple of weeks ago, I purchased a weed puller that does quite a job on dandelions. The puller has a claw at its base. I push the claw down around a dandelion and with my foot braced atop a kind of lever, I lift the flower, including a good chunk of the root, right out of the ground. I can’t count how many dandelions I’ve pulled since making the purchase. A lot. The tool is efficient. I don’t even like yard work, but this dandelion plucker—it’s savage.

While obliterating dandelions in my yard, I became curious if there was anything unique about the flower, culturally speaking, in Norway. I am aware that dandelions have for centuries been used for medicinal and dietary purposes. Victorians used dandelion for salads and mild laxatives. The younger leaves are better for salads, as they’re less bitter tasting. The older leaves can be chopped and used in stir-fries or as a substitute for chard or other greens. They are bitter though. Dandelion roots can be boiled into a mild coffee tasting liquid. The flavor isn’t bad, and it does taste a bit like coffee.

Next comes the magic. The custom, for instance, of holding a dandelion flower up to someone’s face to see, by way of a golden reflection, if that person is in love. Or to snap off the flowerhead into someone’s unsuspecting face as a gotcha moment. This is one trick I’ve experienced weirdly enough over and over in the far north, being the victim, as I have been, of children and beautiful women. There is the familiar ritual of blowing the seed parachutes into the wind. We pick a flower, make a wish, and in order for the wish to come true, all the seeds must be blown free by the wisher in a single breath.

I wrote to my Norwegian friend Kristine B. Fostervold about them. Kristine is not, as far as I am aware, a flower or plant person, but she is a well-studied translator. I wanted to learn more about the words, vanlig løvetann. Kristine wrote back, saying “The word vanlig means ‘common,’ but it doesn’t really do anything here except to indicate how commonly you might find the flower. Otherwise, the name for the flower is purely løvetann, and it’s an ugress in Norway. Løvetann is ‘lion’s tooth,’ and ugress in Norwegian means ‘undesirable,’ as in a weed. It can also indicate the least rare sort of flower. But outside of a garden, not all of them are equally annoying.” That’s Kristine. True to her northern roots, she gets to the point but still gifts a suggestion of something more.

After writing Kristine, I started chasing words again. The word we English speakers use, “dandelion,” apparently comes from the French, “dent-de-lion,” which, like the Norwegian, translates as “tooth of the lion.” Now look at our word dandelion—dan-de-lion. See the French? The taxonomy of the flower is Taraxacum officinale, and with that, there are more journeys to make—deeper into Latin, into Arabic, healing herbs, traditional remedies, simples, classifications, and, as I should hope, legends. Like any number of flowers and a handful of weeds, words carry their own magic.

But what of all this writing about dandelions and what began as finding a way in? A way into what? Another record, perhaps. Another thing or moment of life keeping life in the most visible yet least apparent ways.

I recall the Emily Dickinson poem, “I cannot live with you,” and its magnificent last stanza, which reads:

So We must meet apart –

You there – I – here –

With just the Door ajar

That Oceans are – and Prayer –

And that White Sustenance –

Despair –

Consider these words, from the third and fourth lines, “With just the Door ajar/That Oceans are.” I intentionally do not complete the fourth line. But read closely. We can sense both the intimacy and familiarity of a door ajar. It is a thing that is close to us, a thing we recognize. The door on the other side of my desk is ajar at this moment, and I can see an edge of light coming from the kitchen window. Similarly, on the other side of Emily’s door, are Oceans—an awesome depth just beyond the door. Both the door ajar and the Oceans speak of what is close and what is far. This represents a kind of paradox, one suggested at the beginning of the poem with the opening lines of “I cannot live with You—/It would be Life.” To read more closely, consider that this love endures because distance brings us closer together. Distance brings you closer to me, in all of your intimacy, and the implied tension must remain if we are to remain. So we might understand or so we might read. From there, we can spend the rest of our lives in a chilly house, scribbling out lines of despair on the corners of mere paper and scraps of letters and envelopes.

A door ajar, a dandelion—there is a vastness.

***

The carpenters arrived earlier this morning than I expected. The bathroom is still in pieces. Some of those pieces are in the yard. What started out as a bathroom remodel has turned into a full scale do-over. Given the circumstances of my house and because I’ve been fairly silent lately about a new film we are developing, I emailed Charlie Pepiton not long after the remodel started to tell him that there are “no walls, no ceilings, no floor—just an empty gash on a corner of our house.” There are times when I might be reading Dickinson or dandelions or the paintings of my friend Tabby Ivy, and nature calls. Soon enough I will be scurrying among the woodland creatures and rype living across the road. Except I will be carrying a small camping trowel.

The carpenters are a father and son team. I am not sure how old the father is but the son is a few years younger than me. I walked out to say hello this morning and to bring them each a cup of coffee. The father has had family in the area for generations, and I wish to learn more about them. One serious hang-up in our conversations is that my Norwegian reaches the level of a two or three-year-old child, though a three year old may be a stretch. The younger carpenter has fair English, and the father has less. Nevertheless, I plough along with my questions, which usually come first thing in the morning. I am confident both men would prefer to build my bathroom rather than listen, as they patiently do, to my meddlesome questions, spoken as they are in a distracting mixture of English and Norwegian. The latter of which I do not apologize for, however. As I tell them, jeg må prøve mer Norsk—painful though it is.

Usually, my questions are not very specific. I mostly want to learn about what happened during the war years. I ask about who lived here and what life would have been like at that time. I appreciate knowing about a couple of the older buildings we have in our area. I don’t care for many of the newer ones, the new hytter and nausts. Call it a prejudice. But worlds are leaving us all the time, and I want to make a record of some of them before they are gone, and before I am gone, too. They are ruins, these older buildings and farms. They are not the ruins of an ancient kingdom or city state, but ruins, nonetheless. And ruins are what become of us. That is part of why we save them, part of why we have even built them.

There is a building east of where I live that is in a process of being torn down. It is a shaky wooden structure, and the locals are concerned for the safety of children who explore these kinds of buildings in our area. My heart leans with the kiddos on this one. I relished opportunities to explore abandoned buildings when I was a kid. The building down the road, or what is left of it, once housed the post office and shop or butikk for the village. I have no idea when the building was constructed, but I am sure it has existed from a time before there was a paved road in our area. The carpenters said the German army took over the butikk and posten during the war years. The other night I took photographs of what’s left of the building. I found myself questioning why the German army needed to takeover this place. This place is the back forty of nowhere, and it has been this way for a long, long time. I thought, too, about the people who had lived here during the war. For some of them, their children and their children’s children live here today. Their lives were not so different than they are now—unassuming carpenters, farmers, fishermen, plumbers, teachers. They built what they needed, drank a little extra on the weekends, survived the winter, and sipped coffee and ate brød in sunlight whenever they had sunlight. As they still do. But the German army was here. They built bunkers along the coast. They managed the population. Then they burned down everything they could on their way out of the country—except here. The war ended before the Germans could set our little village on fire. It is difficult to comprehend such madness in the overwhelming presence of the mountains and fields here. They are beautiful. Beauty, I guess, doesn’t keep us from madness.

I have studied enough history to appreciate that history generally repeats itself regardless of our knowledge or intentions. Wrongs, and curiously the same wrongs, happen over and over again. But I can be as wrong as the next fella if I start believing that I am (somehow) unshakably correct in my judgements. While I have discernments, naturally, they do not keep me from being a crappy person sometimes. Thanks to Bob Dylan, I sleep with one eye open when I wander. That one eye is usually turned on myself. After all, the quality of being a concerned citizen and an outright asshole can be measured in breaths.

More fundamentally, when taking in stories and places of historical consequence, there are opportunities to consider our experience in relationship to those other worlds and other peoples. We only start to see and only start to listen when another’s story can be freely told. That is the place from which we begin. We do not abandon our discernment. We can form other conclusions. But the story must be experienced and told freely. I am fortunate in that I often encounter people and places of historical consequence as they are. This means, much of what I see, like the old butikk og posten up the road, has not been harvested or bracketed by a museum. The carpenters are not curators. Yet there is always an arrangement for how a story is told and how a story is recorded. The arrangement can suggest a kind of poetry, one that represents what story has been told and how someone has listened. Like reading poetry, we may not understand all of the words or their many meanings, but we can recognize something has been framed for us. Whatever is on the inside of that frame, if nothing else, begs for us to listen and to look.

So when one of the carpenters told me a pair of German army boots had been found in his mother’s house, I responded with my best Norwegian ja, ja. While my mind went searching for the story of why a pair of German boots had been found in his mother’s house, the carpenter told me the original house where the boots had been found had burned down, and a new house now stands in its place. That was all he said.

***

The last time I rode the bus, I glanced at the property where the new house stands. I tried to take in, as best I could, the countryside surrounding the house. I wanted a sense of the topography. This is something I do when I visit ruins. I look at the ground. I try to understand why a building, a camp, a house, a grave, a sacred tree stands where it does or where it did. I am curious about what more remains. And I ask the question, why here?

Riding past the house, I thought about the German boots. I wondered what they had looked like. I wondered how they had ended up in the house. Then I remembered the land where the old house stood is close to a place where the ghost of a German soldier is said to have wandered up from the sea. My friend Tron told me this story. He said that when his step-grandmother had been a young woman, her mother-in-law had watched her walk up from the beach and along the road with a strange man following her. The man was a German soldier. The mother-in-law stood in her kitchen and kept an eye on her young daughter-in-law and the soldier from a window, as they took their way up to the house. When the young woman entered the house, her mother-in-law came out of the kitchen to meet her and, she must have thought, the man who had been walking behind her. But there was no man.

As Tron told me, the mother-in-law asked his then young step-grandmother, “Who was that man with you?”

“What man?”

“The man who came with you from the sea.”

“The was no man.”

“The soldier?”

“There was no soldier.”

Once again, the story ended.

Tron said no one has seen the ghost in a while. Some believe the ghost is made-up. Tron shrugged and said he wasn’t sure.

“Maybe there was a ghost,” he said. “It could be true.” He paused and then said, “At least I have the story. It is in here.” He pointed at his head.

The bus went past the house and past the place where the soldier is said to have walked up from the sea. All these stories. The family lines of mother-in-law, step grandmother, grandmother, my children, her children, our children can make quite a tangle. I settled back into the seat and looked out the window. There were long fields of yellow flowers stretching between old houses and barns. The sea was out beyond them, and it moved between mountains. I wanted to breathe all of them into me. Home was just up the road.

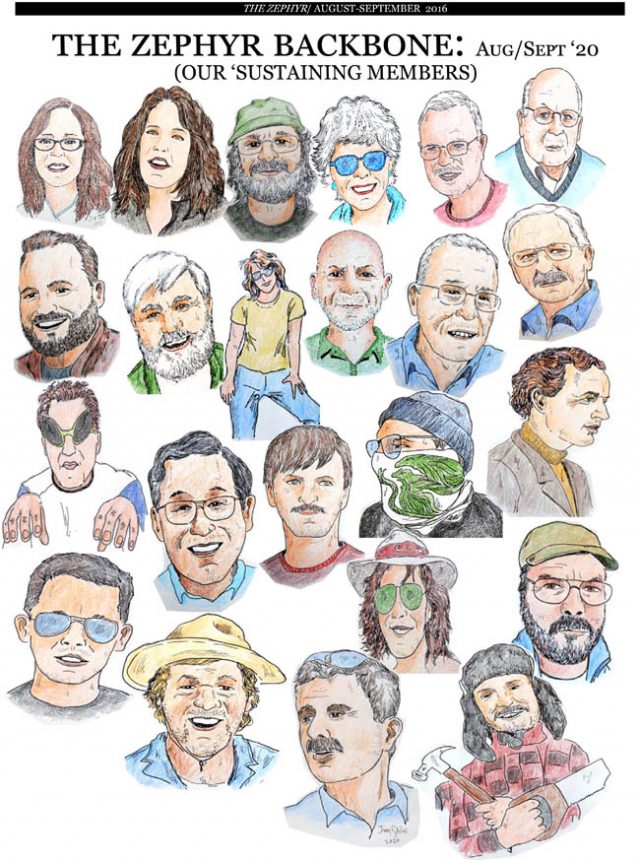

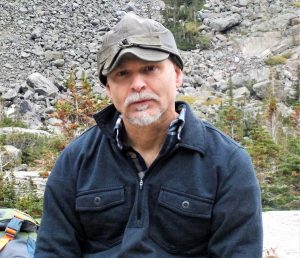

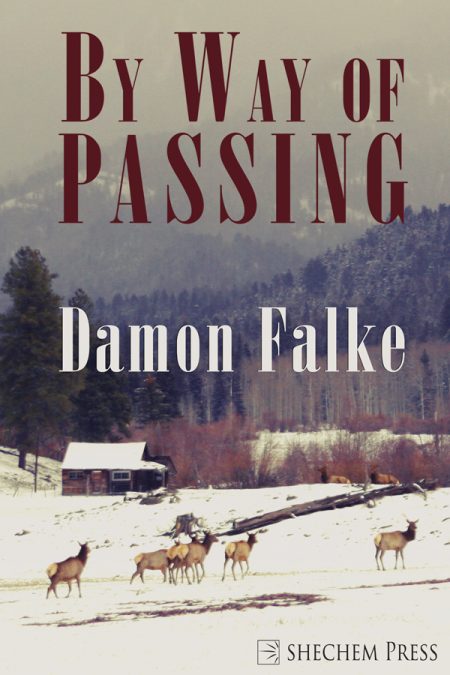

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently The Scent of a Thousand Rains and the forthcoming film Koppmoll (2020), which explores memories of War World II and home. You can find out more about his work at: damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Loved the stories and flow of your writing. I put it down having just read of your bathroom being gutted. When I started again there was the picture of the torn down house! I thought oh my gosh they have a lot of work to do! Then I backtracked as I realized that picture was part of the story! Hope you soon have a working bathroom!