Author’s Note: Last issue, we published “Part One” of this two-part essay. Part One provided the backstory for a very particular time and a place–Yosemite Valley at Christmas, 1943.

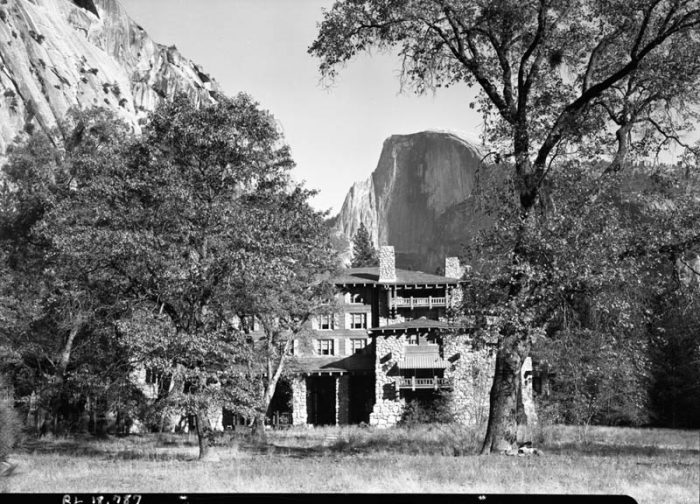

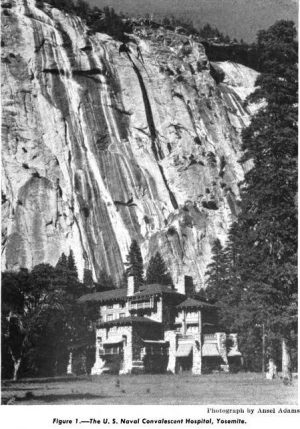

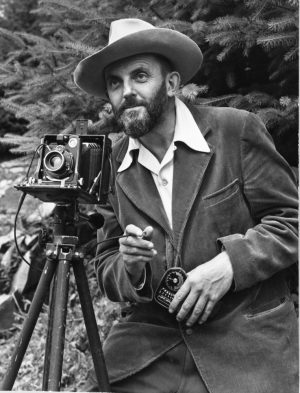

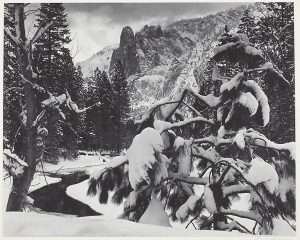

Photographer Ansel Adams lived and worked in the Valley, and he had written a Christmas production, the Bracebridge Dinner, that was performed yearly at the Ahwahnee Hotel. He returned faithfully each year for the holidays. In 1943, though, Yosemite Valley had changed. The Ahwahnee Hotel had been pressed into service as a Naval Hospital, for wounded men returning from battles in the Pacific. Commander Reynolds Hayden, with his staff and the help of Chaplain Gerber, had begun to shape the hospital into a functioning center for rehabilitation and care. Meanwhile, Ansel Adams struggled to find some role to play in the War effort…TS

Just dream yourself for one hour in a chasm nearly ten miles long, with egress, save for birds and water, but at three points, up the face of precipices from three thousand to four thousand feet high, the chasm scarcely more than a mile wide at any point, and tapering to a mere gorge, or canyon, at either end, with walls of mainly naked and perpendicular white granite, from three thousand to five thousand feet high, so that looking up to the sky from it is like looking out of an unfathomable profound—and you will have some conception of the Yosemite.

–Horace Greeley. “An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859.”

“If man ever feels his utter insignificance, his infinitesimal importance as a mere atom in the scheme of things, it should be when gazing upon this scene of appalling grandeur so charmingly blended with transcendent loveliness.”

— “The LORE and the LURE of YOSEMITE by Herbert Earl Wilson. 1922

ADAMS FINDS HIS WARTIME ASSIGNMENT

Ansel Adams returned to Yosemite Valley in the Spring of 1943, having spent the past year fruitlessly seeking some military duty. He’d hoped for work with Edward Steichen, photographing aircraft. Then he had taken a job at the Art Center School in Los Angeles, thinking that the Signal Corps would send its men there for training. The Signal Corps didn’t appear. The job was ghastly. His last assignment at the Art Center was instructing Civil-Service workers on the photography of corpses. Adams was fed up.

So, in March, Ansel Adams resigned from his post and returned to Yosemite. A letter had arrived for him from the editor of U.S. Camera. With excruciating timing, the editor informed him that his nature photography had no place during wartime. He was now unpublishable. Ansel’s unique vision of naturalistic patriotism, with which he hoped to inspire Americans with visions of their own country, was unsuited for the moment. He withdrew with frustration to the isolated valley. He took a few small commissions, one of which involved shooting photos of the newly commissioned Naval Hospital at the Ahwahnee Hotel, before its conversion. But, as the wounded soldiers began arriving at the hotel, he retreated to his studio, seemingly without any role to play in the war around him.

When his friend Ralph Merritt visited in the late summer, Adams complained to him, “I’ve got to do something. After all, I’m feeling like—not a traitor—but I’m perfectly well, and I have a lot of ability along certain lines, and I can’t get in any photographic thing to do in the defense picture. They don’t want photographers.”

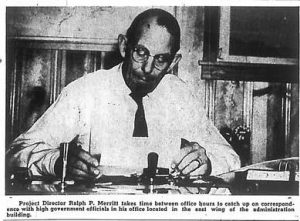

Merritt, who had known Ansel for years through the Sierra Club, encouraged Adams to continue shooting his nature scenes. He told Ansel, “I feel that when the war is over, these will be useful to our country.” But as the two men talked, Merritt had another thought. He had just been appointed to a new job, and he saw an opportunity for his depressed friend.

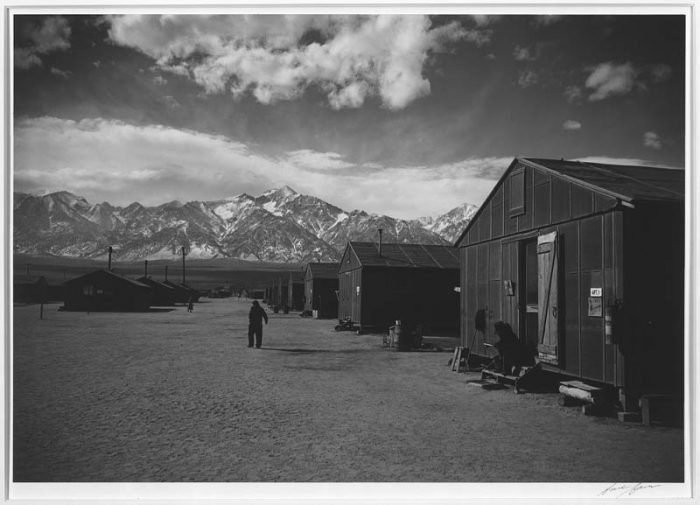

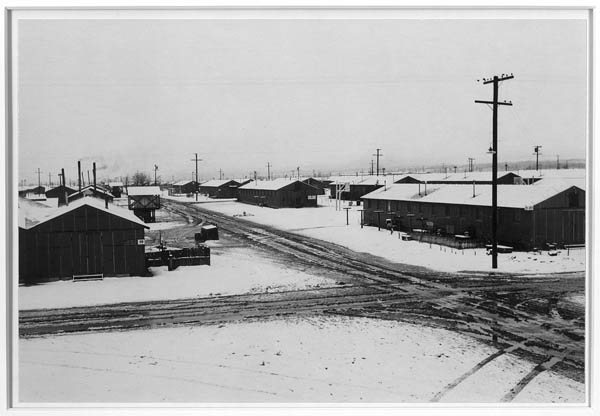

Merritt was the new director of the Manzanar Relocation Camp in the Eastern Sierra, looking after the Japanese Americans who had been detained there. Personally opposed to the camps, he described them as a “fundamental wrong” to Adams. He’d been brought in as director after a series of ineffectual and unsuccessful colleagues. Tensions in the remote camp had reached a head. With patience and diligence, he was pleased to admit that he’d managed to subdue the internal fighting. He’d set up a system of self-government and encouraged the internees to develop a culture as close to their normal lifestyle as possible.

“I do have a project,” he suggested to Ansel, “that might interest you.” He continued, “I cannot pay you a cent, but I can put you up and feed you.” His idea was for Ansel to come to the camp and photograph what was happening there, which he saw as a direct credit to the incredible perseverance and ingenuity of the prisoners. According to Ansel, Merritt said, “We think we have something at Manzanar. We’ve been able to get these people in all our destitute, terrible condition to build a new life for themselves. A whole new culture. They’re leaving here with a very good feeling about America. They know the exodus was a fundamental wrong, but they said, ‘This is the situation—make the best of it.’ If you can photograph that, it’s a very important part of the record.”

Ansel, who had always been dedicated to landscape photography, felt challenged and intrigued by the offer. He himself had been deeply upset by the bigotry of his fellow Californians toward the Japanese. His family’s longtime employee, Harry Oye, was a Japanese national who had been detained only two days after Pearl Harbor. He knew the early conditions in the camps had been dreadful, thanks to the early Manzanar visits of his colleague Dorothea Lange. And he saw the potential in Merritt’s idea. If Americans could witness the fortitude of these prisoners, who had managed to forge a life for themselves out of the barest scraps, then support for the camps might wane. The Japanese could return to their communities without fear. He gratefully accepted Merritt’s proposal.

Adams’ first visit to the camp was October 25th of 1943. He discovered immediately that his friend was correct in his assessment of the prisoners, who appeared to Ansel to be almost universally “positive” in their attitudes. He later wrote:

“I was met by Ralph and his staff, led to my quarters, and then given a cursory tour of the camp. Under a low overhang of gray clouds, the row upon row of black tar-paper shacks were only somewhat softened by occasional greenery. However, the interiors of the shacks, most softened with flowers and the inimitable taste of the Japanese for simple decoration, revealed not only the family living spaces but all manner of small enterprises: a printing press that issued the Manzanar Free Press, music and art studios, a library, several churches (Christian, Buddhist, and Shinto), a clinic-hospital, business offices, and so on…Everyone seemed constructively occupied, alert, and cheerful.“

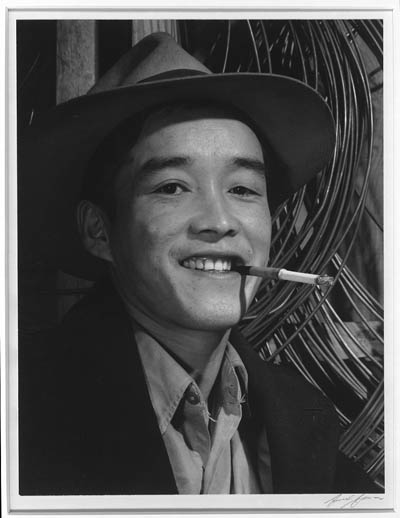

In his estimation, the families at Manzanar had built something incredible out of nothing. They felt a pride in their own perseverance that shone in their faces. In the only portrait-based assignment of his career, Ansel focused in that fall and early winter of 1943 on the individual personalities of the men and women he encountered in the camps. He shot portraits, close-up, and labeled the images with their professions as well as their names—nurse, farmer, tractor driver, commercial artist. He shot a Town Hall meeting. The nurses at work with their patients. The farmers fixing their tractors. His entire photographic repertoire up to this point had been subtle and evocative, but now he made a hard turn toward the overt. The overwhelming message of his photographs was, “These people are just as American as you are.”

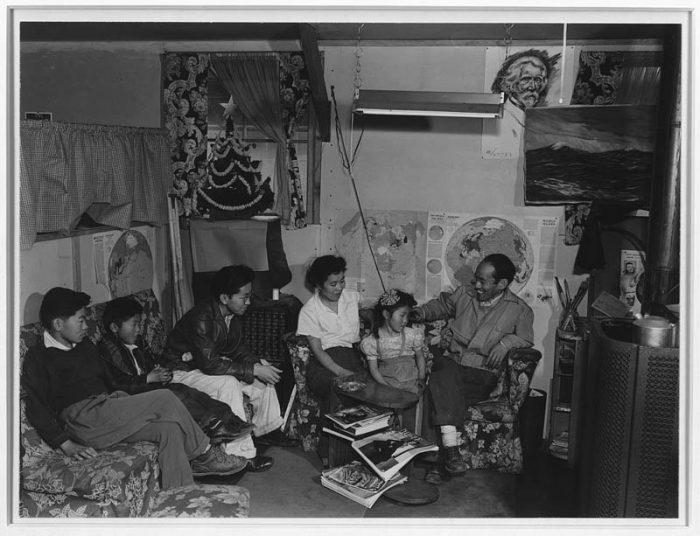

And, at Manzanar, he befriended Toyo Miyatake, a professional photographer from Los Angeles. Miyatake had smuggled into the camp the materials for a crude camera and was already engaged in shooting life in the camps from inside. Adams took multiple pictures of Miyatake’s family—in one shot, taken on his return visit in December, the family sits in their cramped but homey quarters. Toyo is smiling, apparently chuckling, as he looks down at his daughter. A small, decorated Christmas tree sits by the window.

Adams wrote later that he was “profoundly affected” by Manzanar, its inhabitants and its desolate beauty. He was drawn to its grand view of the Sierra. Before leaving Manzanar to return home for the holiday, Adams woke early one morning—before dawn. He and his wife Virginia, whom he’d brought along on that second trip to the camp, drove to Lone Pine.

“I selected a spot not far from the main highway, parked the car, and set up my camera on the platform. We then huddled together in the car, gratefully sipping from a thermos of steaming coffee that Virginia had prepared. Soon, the sun rose above the Inyo Range behind us, glowing pinkly upon the Sierra summits. I scrambled up to my camera, knowing the time was close but feeling it was not quite right. Beams of light began highlighting the brushy trees in the foreground of my composition; they also illuminated the rear end of a horse as it calmly grazed in front of the trees. Frustrated, I watched as the light appeared, just as I had hoped. Serendipitously, the horse momentarily turned to profile and I made the exposure. Within seconds, the tonal variety that created the mood of the scene was destroyed by a flood of even sunlight.”

The resulting photograph, Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada from Lone Pine, CA 1944, would become one of his most famous.

Christmas at Manzanar, that in-between place—a home, and not a home. A desert in the mountains. Those thoughts were on Ansel’s mind as he returned to the Ahwahnee for his own holiday. The hotel turned hospital was now its own in-between world, filled with soldiers caught between the battlefront and home.

THE CHRISTMAS OF 1943

“For many Americans,” the Chicago Tribune noted, “this will be the saddest Christmas of their lives.” A subdued spirit hung over the country that winter, as advertisements reminded shoppers that, by forgoing their own holiday turkey, they could help ensure that enough birds were available for deliveries to their boys overseas and at bases throughout the world. 33 million pounds of turkey were shipped overseas, with 25 million reserved for men stationed at home. Families had sent their gift packages to their absent sons and husbands months earlier, in September and October, hoping the gifts would reach their far-flung destinations in time for Christmas morning.

Holiday light displays were canceled in most cities to preserve electricity and light bulbs. The Tribune sighed, “The memories of fat years before this lean era returned as slim cardboard cutouts of small Christmas trees were hung on street lamps instead of the gigantic garlands and wreaths and gargantuan red bows of wayback.” Even the President’s wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, announced that her gifts that year would be restricted to stamps and war bonds, save for a few presents for her grandchildren.

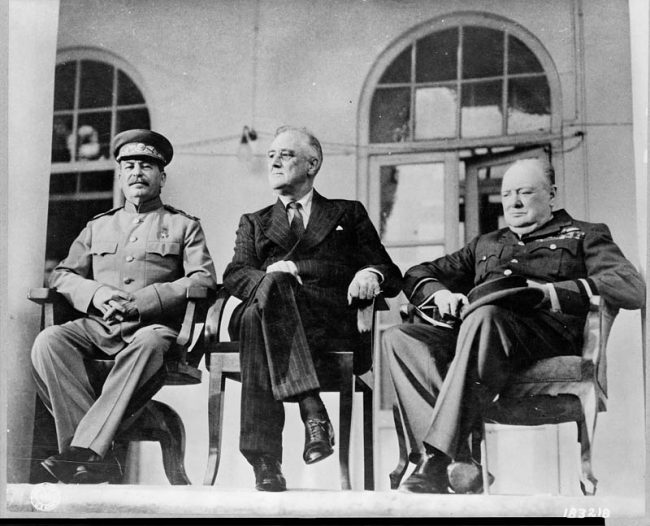

Despite the national aura of melancholy, President Roosevelt remained exceedingly popular. A December 15, 1943 Gallup poll put his approval rating at sixty-five percent. With the military families, it was certainly higher. It was generally accepted that the soldiers had no greater champion at home than Roosevelt. The President had served as Secretary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson and appealed continually for greater duties in the First World War. All four of his sons joined the military, and he saw that they weren’t given any special treatment in their assignments. The Roosevelt family spent those war years with the same dreadful fear as every other war family, not knowing precisely where their boys were at any given moment.

Franklin was beloved by his enlisted men. He had a gift for speaking to them, both as equals and also a father speaks to his sons. The men knew their president had dedicated his own children to the cause. And the wounded men, in particular, felt a bond with him. They were comforted to have a President who understood what it was to be disabled and suffer nightmares. With a remarkable insight, he had chosen not to conceal his condition when he visited the wounded soldiers. He frequently visited their hospital beds from the confines of his wheelchair. On one visit, in July of 1944, at the Aiea Naval Hospital at Oahu, one of his aides, Sam Rosenman, was particularly struck by the scene. Rosenman, the President’s Counsel and speechwriter, recalled:

“He insisted on going past each individual bed. He had known for twenty-three years what it was to be deprived of the use of both legs. He wanted to display himself and his useless limbs to those boys who would have to face the same bitterness. This crippled man on the little wheel chair wanted to show them that it was possible to rise above such physical handicaps. With a cheery smile to each of them, and pleasant words at the bedside of a score or more, this man who had risen from a bed of helplessness ultimately to become President of the United States…was living proof of what the human spirit could do to conquer the incapacities of the human body…Here, in the presence of great tragedy, he was doing it on a grand, heroic scale. The expressions on the faces on the pillow, as he slowly passed by and smiled, showed how effective was this self-display of crippled helplessness.“

The Roosevelt family captured the national sentiment of heroic self-sacrifice that year. Like most Americans, they directed their attentions toward hearth and home at Christmastime of 1943, returning to Hyde Park for their holiday. With two of their sons overseas on active duty, they held close what family they could gather.

Every mind in the country was turned to the war. The most popular Christmastime song was the plaintive “I’ll be Home for Christmas (If Only in my Dreams)”, recorded by Bing Crosby that October with the John Scott Trotter Orchestra and released with Decca Records as a 78 rpm single that fall.

Gifts for children that year were primarily made from wood and cardboard, as metal and rubber were diverted for war use. Even the Lionel Electric Train Company, maker of toy trains, had been diverted to building precision instruments for the Navy. Desirable presents included wooden guns, model airplanes, and patriotic costumes, so that children could feel they were fighting alongside their absent family members.

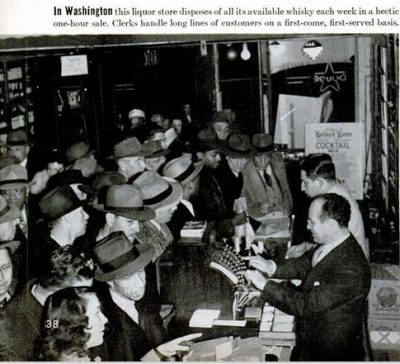

Whiskey and cigarettes were scarce, and stores were bombarded with demand for greeting cards to be sent overseas. Worries about Christmas tree shortages drove up prices beyond what many could afford, and companies like SPAM and JELL-O offered helpful recipes to adapt traditional recipes to the lean times. New York Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia entreated his citizens to avoid turning to the black market for their Christmas meats. Ads for perfumes, toiletries, and foods all pressed their customers to buy war bonds in addition to their products.

And there was a general concern that no one be forgotten. The Japanese American Citizens League partnered with Christian organizations to gather presents for the Relocation Centers. The Gila News-Courier of Rivers, Arizona announced that “not a single child in a relocation center will be without a gift come Christmas morning.” Among the care packages that arrived at Manzanar that year, a letter from a Midwestern community leader expressed prayers that “evacuees” could “soon resume normal community life in our land.” The writer said, “my daughter, age 5, first heard about the Japanese American evacuees and said simply, ‘but Americans don’t do things like that.’ I think it was her first disillusionment about her country.”

And like the internees, the men at the Ahwahnee prayed for some holiday cheer to arrive from outside their Valley. Newspapers and the Red Cross organization had solicited presents around the country for the men at the military hospitals. They knew preparations had been made for parties, and gifts. But still, a spirit of sadness and quiet melancholy hung in the halls of the Hospital.

On Christmas Eve, the soldiers at Yosemite gathered, like all their families at home and all their friends and fellow soldiers on battlefronts across the globe, to listen to the President speak about faith, and the hope for peace. “Tonight,” Roosevelt intoned, “on Christmas Eve, all men and women everywhere who love Christmas are thinking of that ancient town and of the star of faith that shone there more than nineteen centuries ago.”

He continued:

“American boys are fighting today in snow-covered mountains, in malarial jungles, on blazing deserts, they are fighting on the far stretches of the sea and above the clouds, and fighting for the thing for which they struggle. I think it is best symbolized by the message that came out of Bethlehem.

“On behalf of the American people — your own people – I send this Christmas message to you, to you who are in our armed forces:

“In our hearts are prayers for you and for all your comrades in arms who fight to rid the world of evil.

“We ask God’s blessing upon you — upon your fathers, mothers, and wives and children — all your loved ones at home.

“We ask that the comfort of God’s grace shall be granted to those who are sick and wounded, and to those who are prisoners of war in the hands of the enemy, waiting for the day when they will again be free.

“And we ask that God receive and cherish those who have given their lives, and that He keep them in honor and in the grateful memory of their countrymen forever.

“God bless all of you who fight our battles on this Christmas Eve.

“God bless us all. (God) Keep us strong in our faith that we fight for a better day for human kind — here and everywhere.“

CHRISTMAS AT THE AHWAHNEE

At the Yosemite Naval Hospital, Christmas was Captain Reynolds Hayden’s opportunity to show that the Ahwahnee was finally on good footing. The Hospital had survived the summer’s rough start, grappling with the despair of the neuropsychiatric cases who couldn’t tolerate the Valley’s rocky claustrophobia. Hayden had been given a nearly impossible task, to devise forms of recreation, rehabilitation and diversion for the men who arrived at the hotel-turned-hospital on the banks of the Merced River. But, after three months of work, morale was on the upswing. The VFW of the San Joaquin Valley put on a pre-Christmas show and Austrian-born Father Gerber held the hospital’s first Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve.

Ansel Adams had returned from Manzanar just in time for the celebrations, and absent the traditional Bracebridge Dinner, he fell into his role at the Ahwahnee as best he could. He was planning the decorations and lighting for a combined soldier and WAC show the night after Christmas, with an orchestra from the Merced Army Air Field and a dance to follow. But first he threw his efforts into the arrangements for the large “Santa Claus Party” on Christmas Eve in the hospital mess hall.

For the Christmas Eve party, the hall was decorated with large wreaths all around and a 27-foot Christmas Tree. One of the hospital staff, Lt. William Dewgaw, played a hearty, if thin, Santa Claus. Dewgaw, performing with professional entertainers from the nearby towns, handed out presents donated by local Red Cross chapters, the San Francisco Examiner and the U.S. Christian Commission of Pasadena.

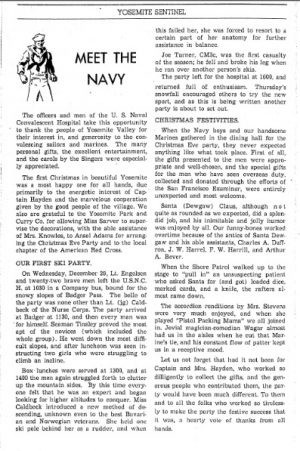

In the January issue of the local Yosemite Sentinel, the Navy boys put out their words of thanks to the community and their captain. Their section, titled “From the NAVY” read:

“The first Christmas in beautiful Yosemite was a most happy one for all hands, due primarily to the energetic interest of Captain Hayden and the marvelous cooperation given by the good people of the village. We also are grateful to the Yosemite Park and Curry Co. for allowing Miss Sarver to supervise the decorations, with the able assistance of Mrs. Knowles, to Ansel Adams for arranging the Christmas Eve Party and to the local chapter of the American Red Cross.

“When the Navy boys and our handsome Marines gathered in the dining hall for the Christmas Eve party, they never expected anything like what took place. First of all, the gifts presented to the men were appropriate and well-chosen, and the special gifts for the men who have seen overseas duty, collected and donated through the efforts of the San Francisco Examiner, were entirely unexpected and most welcome…

“Santa (Dewgaw) Claus, although not quite as rounded as we expected, did a splendid job, and his inimitable and jolly humor was enjoyed by all. Our funny-bones worked overtime because of the antics of Santa Dewgaw and his able assistants, Charles A. Daffron, J.W. Harrel, F.W. Harrill, and Arthur A. Bever.

“When the Shore Patrol walked up to the stage to ‘pull in’ an unsuspecting patient who asked Santa for (and got) loaded dice, marked cards, and a knife, the rafters almost came down.

“The accordion renditions by Mrs. Stevens were very much enjoyed, and when she played ‘Pistol Packing Mama’ we all joined in. Jovial magician-comedian Wagar almost had us in the aisles when he cut that Marine’s tie, and his constant flow of patter kept us in a receptive mood.

“Let us not forget that had it not been for Caption and Mrs. Hayden, who worked so diligently to collect the gifts, and the generous people who contributed them, the party would have been much different. To them and to all the folks who worked so tirelessly to make the party the festive success that it was, a hearty vote of thanks from all hands.“

The soldiers presented a cheery face for their community and did their best to get into the spirit of the season. Later, Mrs Lawler, the wife of the chief Medical officer, spoke at the Salinas Navy Mother’s Club about how much the boys had treasured their Christmas party. She reminded her audience that, while the majority were desperately homesick for their families, many of the men had no family at all. She stressed to the women that, if the Navy Mothers visited the wounded men personally, they might relieve some of that loneliness, which would aid the men’s ability to heal.

THE MEN WHO COULDN’T FORGET

As Adams oversaw the Christmas festivities, he was already anticipating a return to Manzanar for January. He was planning an exhibition of some of the photographs he’d taken that fall. And while he was nervous to see the detainees’ reactions to the photos of themselves, he felt it was right for the camp residents to see the photos first, before the general public. He knew the reception from the broader population wouldn’t be universally supportive.

Further, he knew that his reception among the men at the Naval Hospital would never be the same. “They’d been over there fighting the Japanese,” he remembered, “and they didn’t trust anybody.” He seemed to understand their prejudice, even if he didn’t condone it.

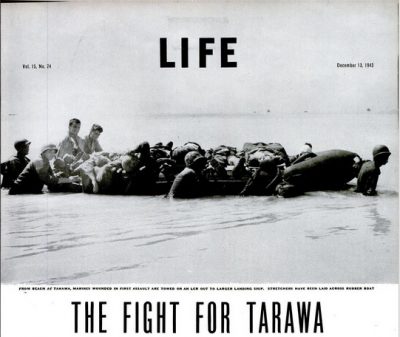

The news that Christmas was still full of reports from the previous month’s terrible battle at Tarawa, in which over a thousand Americans were killed and over three thousand were wounded. Fate and low tides had stranded the American boats hundreds of feet offshore, and the surviving boys had waded through the coral reef toward the narrow beachhead under ceaseless gunfire, while bodies dropped around them. When they finally reached the shore, the Japanese fought brutally, to the last man. In three days, the soldiers had witnessed more carnage and violence than ever before in the Pacific. By Christmas, the wounded from Tarawa were finally arriving at the Naval Hospitals after their long journey back from the battlefront.

And, on movie screens across the country, the film “Guadalcanal Diary” was proving to be a big hit—dramatizing the long bloody struggle for that island, which had only been secured the previous February. Many of the wounded at Yosemite had spent their previous Christmas at Guadalcanal, under constant attack by swarms of Japanese fighters, and ravaged by malaria, dysentery and fungal infections. Even the healthy men, camped out on that distant island, had been grateful if Christmas of 1942 meant a warm beer and an unspoiled orange. Others had fought fiercely in Buna and the jungles of New Guinea, where MacArthur staged the battles that would keep the Japanese from reaching Australia.

The men had heard firsthand accounts of the Japanese army’s brutality toward American prisoners. Torture, mutilations, forced marches and executions. With their own memories so freshly at hand, and the relentless stories of their friends in daily peril, many had little sympathy for the Japanese Americans who had been placed in the camps.

Once Adams’ photographs were published, in 1944, he never again felt welcome among the men at the Naval Hospital. As he recalled, their philosophy was “Ain’t no Jap to be trusted, no how.” He tried to impress on his critics that the men and women in the camps were Americans, and not to blame for the atrocities of the war, but the men at Ahwahnee were too tough a sell. These men were still fighting battles in their dreams each night.

Even among the military men, though, support for the Internment was far from universal. The October 30th, 1943 issue of the Manzanar Free Press ran a letter that had been written by a Marine recently returned from Guadalcanal, addressed to the American Legion Headquarters. The letter read:

Gentlemen:

I am one of the fortunate marines who have returned recently to this country after serving in the offensive against the Japanese on Guadalcanal. After being in the States a while we find ourselves bewildered by a condition behind our backs that stuns us. We find that our American citizens, those of Japanese ancestry, are being persecuted, yes persecuted as though Adolph Hitler himself were in charge.

We find that the California American Legion is promoting a racial purge. I’m putting it mildly when I say it makes our blood boil. We are fighting for freedom for all Americans regardless of their ancestry. Yes, we believe in those things for which we fight and we believe in fighting until we get those inalienable rights, liberty and justice for all, no matter how long it takes to secure them…

Our buddies who are still in the war zone write and ask, “How are things at home? What can we tell them? They will return some day to form a new and greater legion—an AMERICAN legion. We shall fight this injustice, intolerance, and un-Americanism at home! We will not break faith with those who died.

It is our understanding that the real reasons behind this un-American abuse of American citizens of Japanese ancestry are not for military security, but just ugly hatred and lust for economic and political gain. What can be closer to fascism?

We have fought the Japanese and are recuperating to fight again. We can endure the hell of battle, but we are resolved not to be sold out at home.

Yours Sincerely,

Robert E Borchers,

U.S.M.C.R

A NEW YEAR

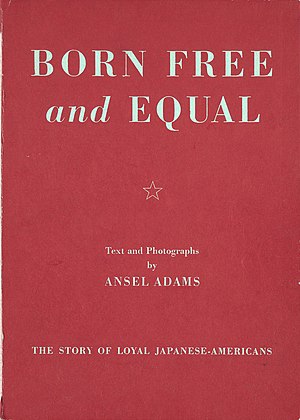

When Adams published his Manzanar photographs the next year in a book titled “Born Free and Equal,” the foreword was written by no less a figure that Harold Ickes, the Secretary of Interior, who felt himself that the so-called Relocation Centers were “fancy-named Concentration Camps.” Ickes lobbied continuously to allow Japanese Americans to return to the coast, and was finally successful. By the Christmas of 1944, the exclusion orders had been lifted.

The Manzanar photos were also shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City that year, though Ansel felt they weren’t accepted as “art” in the way his naturalistic photos had been. The show was relegated to the basement of the museum. Still, it was a popular exposition. Many other photographers visited to see the faces of the Manzanar internees, and the images of their small newspaper office, their town hall meeting. The famed photographer Paul Strand, Adams later recalled, began to wipe tears from his eyes as he walked from photograph to photograph.

And Adams received criticism from all quarters. Some, including Dorothea Lange, felt the pictures were far too upbeat. They felt he’d glossed over the real horror of internment in order to present a cheerful front for the camps. On the other side, of course, he received letters from the families of men who had died on the Pacific front, accusing him of collaboration with the enemy. But still, Adams always believed that his photos of Manzanar—which were so different from the rest of his body of work—represented, from “the social point of view…the most important thing I’ve done or can do, as far as I know.”

At Ahwahnee, morale continued to improve through the winter of 1944 and into the spring. Many of the soldiers learned to ski in the classes at Badger Pass. Hospital staff scrambled to find winter clothes for the men who had been rescued from sunken ships, so that they could enjoy sledding and skiing along with the others. The hospital opened a movie theater for those who weren’t mobile enough to travel to the nearby towns. Eventually, the Ahwahnee was given permission to open a beer pub—the only operating bar at any naval hospital in the world.

Father Gerber left in the Spring of 1944 to return to active duty. He saw four more Pacific battles before he was gravely wounded at Iwo Jima. He survived and returned to open a new parish in Peoria, Illinois where he lived the rest of his life.

In the Austrian chaplain’s place arrived Father Thomas Reardon, a young Irish priest whose name preceded him throughout the country. The first chaplain at Guadalcanal, he’d cared for the soldiers on that remote island until he succumbed to unconsciousness from malaria and had to be brought himself to recuperate at a Naval hospital back home. Familiar to everyone, Reardon happily threw himself into the work of the hospital, writing to the Hospital Corps Quarterly to brag on the performance of Frank DeGrazia on the Ahwahnee News and bringing in a Jewish Chaplain and a Protestant Reverend to help him minister to the wounded men.

THE WAR’S END

By the time the War ended, in 1945, the hospital was a warm and close-knit community. The library was filled with books. The theater showed films five nights a week. The pub was always fully stocked with beer, and the full staff of doctors, employment officers and chaplains looked after each aspect of the men’s return to American life.

Some of the last men to benefit from the Ahwahnee’s comforts were those liberated from Japanese prison camps. These men arrived throughout 1945, as the Allied forces re-took the areas where the prisoners were being held, and finally the men returned from the mainland camps as well. The conditions inside Japanese POW camps had been gruesome and inhuman. The stories were sickening—these men had witnessed public beheadings. They had survived mass starvations and torturous medical experiments. At least 30,000 others had died alongside them in captivity. The survivors arrived back in the U.S. Naval Hospitals still suffering from the after-effects of severe malnutrition, crippled by years of forced labor and torture. At the Ahwahnee, these patients were given a brief opportunity to rest and recuperate among other men who understood what they’d experienced. It was an invaluable aid to the war-ravaged soldiers, who were often terrified by the prospect of returning to their families and the hometowns they had left years earlier.

But eventually, the men had to leave the Ahwahnee. The war was over and the Naval Hospital was no longer needed. Some soldiers were sent back to their homes. Some returned to other duties, as the military adjusted its missions for peacetime. The U.S. Naval Hospital at Yosemite was decommissioned in December of 1945, and turned over, first, to the Bureau of Ships, for deconstruction of the various barracks and naval facilities and then, secondly, returned to the Concessionaires for civilian use.

THE AHWAHNEE’S RENEWAL

The task of restoring the Ahwahnee to its former state fell to Jeannette and Eldridge Spencer, the preferred interior designers of the Curry Company. Over the course of seven months, the Spencers oversaw the complete “rehabilitation” of the hotel. Draperies and rugs came out of storage. The pictures were hung back on the walls. Gone were the bunks and the medical equipment. The office of the Master-at-Arms became again the office of the hotel clerk. The ship’s service store returned to its life as a sweet shop.

By the time of its reopening, for the holiday season of 1946, the Ahwahnee Hotel was completely restored to its pre-war luster and luxury. It would’ve been impossible for any visitor to the re-opened Ahwahnee to imagine how his guestroom would have appeared only a couple years earlier.

And it wouldn’t have been the holidays at the Ahwahnee without Ansel Adams. The Christmas of 1946 also meant the renewal of the Bracebridge Dinner, and Ansel’s resumption of his role at Court Jester at the high-spirited Medieval banquet and pageant, which had been his yearly tradition since 1927.

Life in Yosemite Valley had returned to normal. Visitation to the National Park was high throughout 1946, thanks to the end of gasoline rationing, and the buoyant spirits of a victorious and relieved nation. Returning soldiers, who had pored over tourist pamphlets while they were stationed at various bases across the globe, were anxious to explore their own country. Yosemite, with its grandiose cliffs and awe-inspiring views, was especially popular with the vacationers.

And, with the end of the war, Ansel Adams had discovered a newly receptive audience for his vision of ‘Patriotic Naturalism’. In 1945, he was tapped to form the first fine art photography department at the San Francisco Art Institute. He invited friends like Dorothea Lange and Edward Weston to lecture and appointed Minor White as the primary instructor. With time, the program nurtured some of the greatest photographic talents in the west, including Philip Hyde.

And in 1946, Adams received his first Guggenheim fellowship, so that he could travel and photograph every National Park in the country. There were 28 parks at the time and Adams managed to shoot 27 of them, missing only Everglades National Park. He spent his time, all through that year, in rapturous appreciation of the terrain around him—shooting iconic images of Mt McKinley, of Old Faithful, and the Grand Tetons.

But at Christmas, as always, Adams was where he belonged. At home. He returned, like a nesting bird, to his gallery. To his responsibilities at the Ahwahnee. To his family. Throughout his life, one touchstone remained. No matter what adventures carried him across the landscape, no matter what stresses plagued him, one place and one season always held his heart. Christmas at Yosemite Valley. The snow falling along the Merced River. The icy face of Half Dome overlooking the pine trees. He understood, just as Captain Hayden and the wounded men of the Ahwahnee Naval Hospital had, that this place was special. This hidden valley, preserved in a timeless quiet. It held a power to heal.

Tonya Audyn Morton is the former publisher & managing editor of The Zephyr. She is now the founding publisher/editor and frequent contributor to “Juke,” an arts and literature journal on Substack. Zephyr readers can access Tonya’s page here. And on Facebook.

Click Here to Read Part One…

Selected Bibliography:

* Ansel Adams: A Biography by Mary Street Alinder. (Amazon link)

* “History of the United States Naval Special Hospital. Yosemite National Park, California.” Printed by Yosemite Park and Curry Co. January, 15, 1946.

* “Born Free and Equal” by Ansel Adams. Library of Congress.

* The Hospital Corps Quarterly: Supplement to the United States Naval Medical Bulletin.1944

* The Archives of the ‘Yosemite Sentinel’

* “Yosemite’s World War II Hospital.” National Park Service.

* Conversations with Ansel Adams : oral history transcript / 1972-1975. Ruth Teiser

* Ansel Adams and the American Landscape: A Biography by Jonathan Spaulding. (Amazon link)

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!