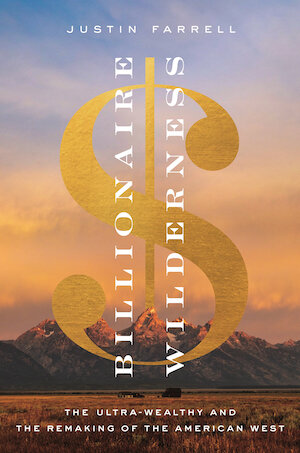

Back in June, a friend sent me a link to a new book that he thought might interest me. It was called Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealthy & the Remaking of the American West. I was able to access a brief introduction and the first paragraph resonated so deeply with me, I immediately placed an order to buy a copy.

In author Justin Farrell’s acknowledgements, he explains his very early and innocent connection to wealth and power— as a small boy he and his brothers often accompanied their mother to work. She cleaned the homes of wealthy people, sometimes as many as seven a week and because she worked alone, each house often occupied the entire day.

Justin observed that, “it was strange and exciting to spend so much time in these expensive homes…it gave us a window into affluence.”

I had my own “window into affluence” experience, though I was a bit older than Justin and was, in fact, doing the mopping and scrubbing myself. In the late days of October 1972, I was in Jackson, Wyoming, pursuing a dream of living “out West,” thinking maybe I could settle here, and almost flat busted broke. A new found friend, Kerry Lanier of Portland, Oregon, told me he’d found work cleaning homes and businesses for a company called the Dustmop Janitorial Service. I applied and was instantly hired (after all, I’d just graduated from college!), and went to work the same day.

The nights were grueling. We had contracts with several of the more popular eateries at Teton Village to clean their kitchens. Kerry and I were both stunned at the unsanitary conditions and vowed we’d never eat at any of these restaurants, though it was also clear that neither of us could afford anything on the menus. It often took until dawn to restore the kitchens to anything remotely “clean;” we’d go back to the shop, crash for a few hours, and then tackle our daytime assignments. They were much easier.

Even in 1972, Jackson and the valley north of it was becoming a mecca for the wealthy. Only a smattering of homes had been built by then, but you could feel the changes. Most notably the singing star couple Robert Goulet and Carol Lawrence had built a home five miles north of town with a magnificent view of the Grand Tetons. But one could see a trend. Kerry and I cleaned four or five homes a week. All of them were situated in that vast open part of Jackson Hole south of the airport. As we drove to the first house, Kerry advised me, “You won’t believe this place.” He’d cleaned here before.

The home was not particularly impressive outside, just a very long ranch house, stylishly appointed with native stone and redwood facade, and a stunning aspen shake roof. But once Kerry turned the key and we went inside, I was speechless. The northwest side of the house was all glass, and granite and marble—the place was oriented to point directly at Grand Teton peak. Even the bathroom had its own magnificent view.

Downstairs, a high ceilinged “grotto hot tub,” with maybe 25 by 30 foot dimensions, partially filled one end of the room. It reminded me more of a quarry. Underwater lights cast strange reflections and shadows on the stone walls. A “recreation room” was available adjacent to it, for anyone who grew bored with the scenery. Clearly no one had cut corners here to save a buck.

We loved these gigs. Our job was easy. Other than picking up the dead flies and giving the horizontal surfaces a light dusting, our biggest task was finding ways to consume the contents of the owner’s liquor cabinet without getting caught. I noticed that he had subtly marked the level of his favorite single malt Scotches and Wild Turkey bourbon with a pen. No hired help was going to drain his ardent spirits. But we found a bottle or two that hadn’t been booby-trapped, so we developed a taste for Drambuie.

A few nights after our cleaning, Kerry and I went to the Cowboy Bar for a beer and he pointed out a rather bland looking middle-aged man sipping bourbon at a table with a very attractive woman. “That’s the guy,” Kerry said. “…the rich dude whose house we cleaned. He must be back.” The owner was usually only there a week or so every month. He flew in on Friday nights and kept a Land Rover parked at the airport for his convenience. He tried desperately to look and act the part of a local, as if he wanted to fit right in, but he couldn’t quite make the cultural leap.

It was my first closeup brush with that kind of opulent wealth, and if I could ever find an attribute of my own that I am proud of, it’s that even then, I never found myself feeling envious of that kind of extravagance; in fact, I found it downright repulsive. I understood wanting a comfortable life. But I never understood making a show of it.

* * *

Jump ahead half a century to 2020 and Billionaire Wilderness. As I turned the pages, I realized that the book in its entirety had focused on what has become the vortex of wealth in the rural United States: Teton County, Wyoming—that very same place I had once worked picking up flies. Almost all of us are aware of the extraordinary beauty that can be found in the northwest corner of Wyoming. It is home to Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks and some of the most breathtaking natural majesty on Earth. But as Farrell notes, “What most people don’t know is that the grandeur of its wilderness is matched by the awe-inspiring concentration of wealth and a canyon-size gap between the rich and poor there: It is both the richest county in the United States and the county with the nations’ highest level of income inequality.”

Justin Farrell is not an outspoken activist for or against the environmental movement. In fact, he’s an associate professor of sociology at Yale University in the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. As Farrell himself notes, his “dual identity,” the fact that he was born and raised in Wyoming, combined with his “Yale professor” status, was beneficial. He explains that “the elite cachet this group attributes to a place like Yale opened the door for my initial access to this exclusive world.”

Over five years, Farrell conducted hundreds of extensive, in-depth interviews with a variety of multi-millionaires and billionaires–oil barons, Wall Street bankers and financiers, venture capitalists—many of them spoke openly and frankly about their own wealth, their perceived self-identities, and the way they believed they were perceived by the less fortunate citizens (financially at least) whom they called their neighbors and friends.

Farrell spent as much time interviewing the rural poor in the area, those who do the real work, and who guarantee the level of comfort that the billionaires have come to expect. Farrell learned that the view looking up was a world apart from the view looking down from on high. And that the friendship that the wealthy believed existed between the rich and the poor in Teton County was a very limited, one-sided perspective.

* * *

If you are a regular Zephyr reader, you know that this publication has invested at least part of the last two decades trying to convince our readers that the influence of wealth and affluence on the landscape and human environment of the West produces damage of its own. We first raised that topic exactly 20 years ago today, with an essay I penned called, “The Rich Weasel Factor in the New West.”

I’ve never been much of a diplomat. The title alone tipped my hand. Though rereading the essay all these years later, I’m amazed at how evenhanded I tried to be. Since then, I’ve become a bit less tolerant of obscene wealth and the power it exerts on us all. Consequently, I have never been able to ask the kinds of probing questions that Justin Farrell poses so skillfully to the ultra-wealthy. The consequence of those dialogues is in many ways the greater theme of Billionaire Wilderness. Farrell doesn’t just want his readers to acknowledge the existence of this powerful, transforming force in the American West; he genuinely wants to understand the motivations of the rich. The many conversations in the book are revealing, both in their candor at times, and in their utterly delusional aspects at others. Often the attempt at candor is the delusion.

His interviews with the working poor offer revelations of their own, revelations that their wealthy neighbors might find disturbing. The relationships between the “haves and have nots” in Teton County reflect similar situations and attitudes across the West. Years ago, I think I called it a New West Feudalism. The economy generated by the growing presence of wealth in the rural west has come to be regarded as essential to many, a necessary evil to others. I remember when the venture capitalist David Bonderman bought his Moab property and started building his mega-mansion. He wanted more privacy, so he proposed building a tree blind around the perimeter of aspens and ponderosa pines. Both trees grow naturally at an altitude above 8000 feet. At 4000 feet, Moab is a hot dry desert. So Bonderman hired a man with a big tanker truck to water his trees–hundreds of them—for as long as it took for their roots to reach the water table and establish themselves. The man with the truck was delighted, and it meant a guaranteed job for years. How could he complain?

Still, for many, there is resentment and even a sense of grief, that the influence of this kind of extreme wealth is changing the West in ways many never imagined possible. And most troubling, as Justin puts it, is the fact that “most of us continue to look the other way as a new Gilded West is being built.”

I strongly urge you to read the excerpt we have included from Billionaire Wilderness, and then go out there and buy Justin Farrell’s book. His voice and the story he tells need to be heard and shared.

Click Here to Read “An Excerpt from BILLIONAIRE WILDERNESS: The Ultra-Wealthy & The Remaking of The American West …by Justin Farrell”

Billionaire Wilderness is available for purchase via the Princeton University Press Website. It is also available via Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Somehow our friend Mr Greenspan has managed to survive in Jackson Hole. Every month I’m pleasantly surprised they haven’t tarred and feathered him. I guess them rich folks like their music. They better appreciate the gift he’s giving them.

It is called NEO-FEUDALISM

Thank you Jim for continuing to serve as a research node or clearinghouse on the subject of ultra-wealth invading the west. Farrell’s book looks like a solid contribution to the case to be made. Places like Boulder or Jackson or Park City are just the most noticeable beachheads of the invasion. Out in the back country the gigantic houses are less prominent, tucked away, but still just as self-indulgent.

The pandemic has accelerated a trend here in the Black Hills, serving as an invitation to wealthy rock-ribbed conservatives who admire the loose enforcement of what they consider hygienic puritanism (read: less strict attitudes toward masking) in this part of the high plains. A few are buying and renovating old classic homes, but most are building monster footprints out along the ridgelines and foothills, with expensive views. I do not know if this is taking off in the Moab or Jackson areas, or others like them, but survivalist notions have only made it more virulent. It’s not just an invasion of money, but of a particular brand of neo-liberal imperialism, changing the political ecology as well. (Amazing too how often these newcomers get appointed to commissions or open seats in the legislature.)

We have been calling these folks “carpetbaggers” around here, which seems to mix the sense of pettiness with the rank odor of exploitation and hit-and-run economics. But maybe we need a new name of opprobrium for these Snopeses of the west. And for sure we need a better strategy for slowing them down, or stopping them. This is about more than resentment against newcomers.

Then again, dispossession was visited upon the Indians and the homesteaders before they came after us middle-class squatters. Maybe it’s just our turn. And then how long wiil the billionaire carpetbaggers last?

Thanks again Jim for keeping your nose to the American wheel.

I’m glad Farrell is identifying and examining the phenomenon, but I have a feeling the rich weasels would just laugh at him. Unfortunately, Farrell is likely preaching to the chorus. As a 40-year Boulder resident, I can’t help but object to being categorized in the same bag as Jackson or Park City. Boulder has actually worked pretty hard against Aspenization and, yeah sure, we got our problems with the rich/poor divide, but people like me haven’t yet been metaphorically kicked out of town, like they were in Aspen back in the 80s. Boulder has changed in the 40 years I’ve lived here, but not as dramatically as the national park and ski resort towns.

I think of California when I read your story it is a mirror of what took place at the beginning of the last century so if you need to know how the western U S will endure this invasion look no further than California – the answer is right in front of our face