(NOTE: This installment in my “ranger series” starts during my time at Arches, but the story of tamarisk at the park, and the NPS’s efforts to eradicate it go far beyond my tenure…JS)

* * *

In the last issue of The Zephyr, I made reference to a place I called “The Secret Spring,” in a very remote corner of Arches. Few knew of its existence when I first came upon it in 1976. Here is a quick recap…

...I let my eyes fall to the valley itself, into the grey mancos badlands that dominate the south end of the confusing geology created millions of years ago by a collapsed salt dome.

Within that moonscape, something caught my eye–it was an unnatural flash of green. I reached for my binoculars for a closer look and even from this distance, could make out several large cottonwood trees and what appeared to be a thicket of old tamarisk. I made a note of this anomaly and planned a visit there on my next scheduled backcountry day. The following week, I took my first exploratory hike to a place I’d never heard mentioned by the other rangers. What I found was an odd oasis in the desert.

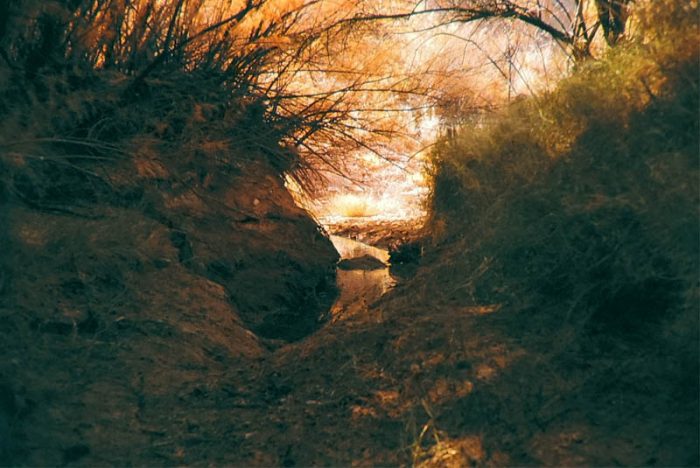

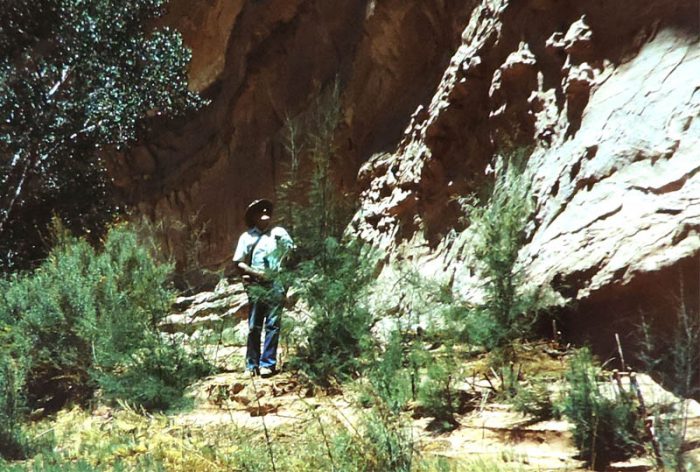

The sight of a spring fed patch of green is startling because it’s so unexpected. The hike to the spring winds through elephant backs of Mancos shale and there is no clue of the teeming life to be found until that last turn of the wash. I emerged from the badlands near the oasis’s southern end and began walking upstream beneath a canopy of tamarisk. Unlike the thickets I was accustomed to along the Colorado, many of these trees were a foot thick–-and there was little evidence of new growth. The floor of the wash began to appear damp and eventually a trickle of water appeared over the sand. Near the north end of the oasis, several mature cottonwoods grew by the wash. Just beyond them, I discovered a pool of water, hidden in the shade of some tammies. Beyond this point, the desert reclaimed the land.

I wondered if I should tell anyone about this magical spot. I hesitated for two reasons—first, even then, I knew that identifying “secret places” could have a devastating effect. Too many well-intentioned admirers can spoil just about anything. Second, I realized that “beauty is often in the eye of the beholder.” A dedicated tamarisk hater would only want to tear it down. In this case, I thought tammie eradication could do more harm than good. So I proclaimed my discovery the “Secret Spring” and decided to keep it mostly to myself. In ten years I revealed the Secret Spring to two of my fellow rangers. While neither of them was a fan of exotic plants, both agreed–the best way to protect this area was by leaving it alone and for a decade, it stayed that way.

I assumed it would stay this way for a very long time. But I was wrong.

I quit the Park Service at the end of 1986, after eleven years as a seasonal ranger. By the following spring, everything had changed. Arches National Park found itself with a new superintendent, a vacant chief ranger position and, for the most part, a new seasonal staff.

Over the years, I learned there are two kinds of career Park Service ranger/managers—those who wanted to protect the parks, and those who wanted to build their career portfolios. Many of us “seasonals” believed that the best managers were those who thought of themselves as caretakers. But we worried about those who always wanted to change the place they’d just taken charge of. Whether it was to promote a new road, or a new visitor center, or push a new resource “management” plan, we feared that dangerous mix of power and ambition that some career rangers exhibited.

The acting chief ranger was very ambitious, and a strong proponent of tamarisk removal. He had discovered the “Secret Spring” on his own in 1985 and moved forward, albeit quietly, with a plan to remove all the tamarisk at the Secret Spring. He was going to burn it, and then poison it.

Only by accident did I become aware of the project. In March 1987, as a civilian now, I made a sentimental hike to the spring, just to visit and to say hello to this quiet spot, and to rekindle some memories. But I was surprised to find a large cache of fire tools near the spring; clearly a controlled burn was in the works. I inquired about the equipment and discovered that indeed a prescribed fire had been planned for March 27, 1987. The fire was postponed until autumn when the NPS could not locate a qualified fire boss to supervise the burn.

The plan called for the burning of the tamarisk in place; that is, the NPS intended to torch the tamarisk where it grew, despite the fact that many of the exotic plants grew near and even under the very cottonwood trees the NPS maintained it was trying to save. Such an approach would have been devastating. In addition, the park proposed to go forward without even writing an environmental assessment. It was to be the largest controlled burn in the park’s history and its largest eradication project using herbicides; yet the NPS believed the project did not require public notification or input.

In the months that followed, I tried to shine as much light as possible on the planned tamarisk burn. Park Service management was bewildered. Just a few months earlier, I had been a government employee, albeit a seasonal ranger, and my opposition to the project would have stayed “in house.” But now, here I was, openly complaining about the project. I’m sure the park hierarchy thought I was being uppity, but they could no longer control me or threaten “termination.” I was a free agent now.

But this was in the pre-Zephyr days, and so I resorted to writing letters to NPS officials, environmental groups, and newspapers, including the Times-Independent, The Grand Jct Sentinel, and High Country News.

At first, the Park Service response was infuriating. The new Southeast Utah Group Superintendent, Harvey Wickware, sent me one of those patronizing “attaboy” letters that the Park Service excelled at. It began:

“Thank you for your concern with Arches. Well-founded criticism keeps us all on our toes and hopefully prevents mistakes that could have disastrous consequences.”

Yawn. The rest of his letter explained, in effect, that it planned to ignore my concerns and proceed with the project. And the new super suggested that I quit annoying him further and limit future discussions of tamarisk removal to the park’s resource specialist. “I think this will be a much more effective method of communication,” Wickware wrote in May 1987, “than us developing letter writing campaigns.”

Arches National Park’s new superintendent, Paul Guraedy also wrote, explaining why I was wrong, and recited some boilerplate information I’d known for years. He insisted that the original March 27 burn date would not have conflicted with nearby Cooper’s Hawk nest and mating season, despite the fact that I saw the hawks in the cottonwoods on March 25. He explained that the nesting season begins in April, but I was undeterred. I replied:

“I hate to be redundant, but it’s vital that you understand the point I am trying to make. Arches essentially closed the Upper Fiery Furnace to visitors on February 1. The concern is over a traditional raptor nesting area. But Redtails lay their eggs weeks later…why isn’t the same concern being shown for the Cooper’s hawks?

He also maintained that the fire would have no effect on adjacent native vegetation, despite the fact that the 50 year old tamarisk trees grew directly beneath the cottonwoods. And Guraedy assured me the fire would spare nearby historic structures, including an old cowboy trough and tank, just a few feet from the burn area.

Guraedy even tried to cite other NPS tamarisk control projects, including the alleged eradication of tamarisk in Horseshoe Canyon at Canyonlands National Park and at Eagle Borax Spring in Death Valley. In neither case did the facts support the presumption of success.

At Death Valley, a prescribed burn had in fact eliminated some of the tamarisk, but at a high price. During the burn, unexpected high winds ignited adjacent rare mesquite (In Death Valley, all native vegetation is rare.). Acres of mesquite were destroyed and years later, NPS rangers still described the scene there as “charred devastation.” My old friend Reuben Scolnik, a long time volunteer at both Arches and Death Valley, showed me the destruction.

As for the Horseshoe Canyon project, the NPS was congratulating itself for “removing” all the tamarisk along several miles of the canyon bottom. Again, Reuben Scolnik and I made a trip to Horseshoe; we counted several thousand new seedlings. In my letter to the superintendent, I wrote that, “between five and ten thousand new tamarisk seedlings had sprouted,” and that “hundreds of cut and treated stumps have sprouted and produced new growth.” many were turning to seed.

Consequently, the park later became more vigilant in its yearly control of new growth, but the lesson was clear—if the Park Service ever walked away from its annual checks, the tamarisk would return with a vengeance (The tamarisk beetle was still years away from being introduced).

Later in 1987, I started writing a column for Moab’s irreverent newspaper, “The Stinking Desert Gazette,” and tried to get more citizens involved in the issue.

Among those who added their voices of concern was Dave May, the former chief naturalist at Canyonlands National Park. Dave’s letter to the NPS was especially effective. Among his observations:

“Tamarisk is a typical ‘pioneer’ species, in that it becomes established in very dense stands on unoccupied habitat where it has no competition; by its growth habits it then modifies the habitat. The forgoing series of events can be seen to be occurring on numerous tamarisk-infected sites in this region, and in every case the tamarisk thickets appear eventually to be invaded by native plants. I know of no sites where the normal sequence of stages in plant succession has progressed to the point of eliminating tamarisk, but there are several at which tamarisk is old and deteriorating and not replacing itself”

This is exactly what was happening at the Secret Spring. In fact, the case could be made that without the tamarisk thickets stabilizing the banks of the wash, the cottonwoods would never have been able to take root in the first place. And indeed, most of the tamarisk were very old; little evidence of new tammie growth could be found anywhere.

Dave also noted that, “The proposed burn would inevitably destroy nesting and cover sites (escape habitat) now being utilized by native animals.” His comments were substantiated by Moab veterinarian Paul Bingham, a raptor rehabilitator and Marilyn Bicking, a well-respected raptor specialist who lived in Moab in the late 1980s.

Cooper’s Hawks, they noted, are accipiters and are not soaring hunters; they prefer a thicket-type environment to hunt their prey, using the foliage of trees as cover. In effect, a non-native plant created a favorable habitat for a native bird.

And a bulletin of the Audubon Society of Western Colorado described the observations of Steven Carothers, an Arizona environmental consultant and a long-time observer of tamarisk in the Grand Canyon. He observed that, “smaller stands of tamarisk will match in bird density, any other type with equal foliage volume. The Bell’s Vireo even seems to prefer salt cedar and has recently extended its range upriver.” In fact, numerous nests could be observed at the Secret Spring site and I asked the NPS to identify them.

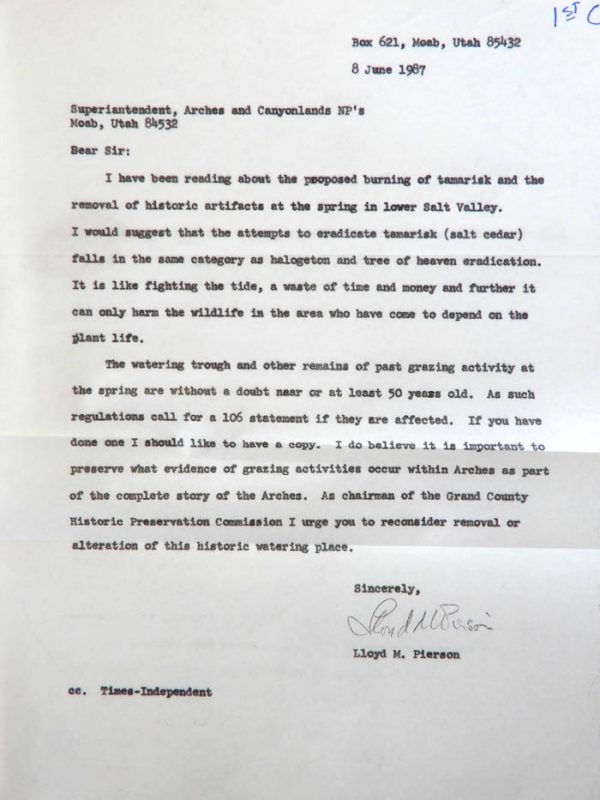

Lloyd Pierson, the Arches chief ranger during Ed Abbey’s tenure at the park, weighed in. He wrote to the superintendent:

“I would suggest that attempts to eradicate tamarisk…is like fighting the tide, a waste of money and further it can only harm the wildlife in the area who have come to defend the plant life.”

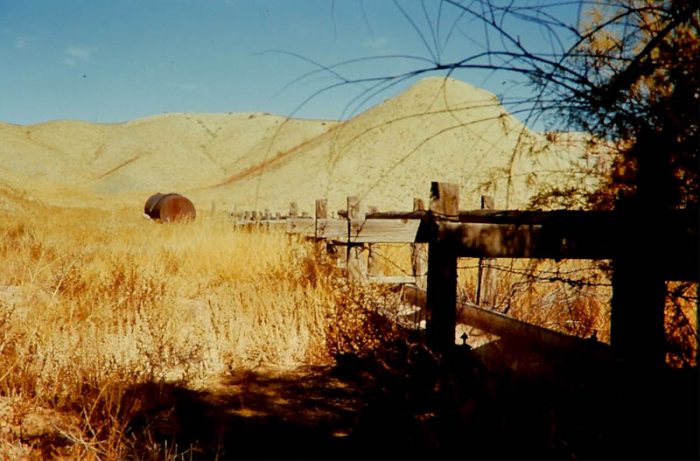

At the time, Pierson was chairman of the Grand County Historic Preservation Commission and expressed concern about the threats to historic structures from the fire. “I believe it is important to preserve what evidence of grazing activities occur within Arches as part of the complete history of the park.”

His reference to “historic structures” included an old 500 gallon steel tank and wooden trough that resided on some benchland above the spring. In addition to the proposed burn, the NPS had suggested it might burn the trough as well. As for the tank, one ranger speculated that a welder could cut the tank into pieces and then they could hire a helicopter to haul the dismembered tank to a more suitable location. All at a cost of a few additional thousands of dollars.

Then Ed Abbey himself leapt into the fray. The debate gained some coverage in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel. I took Abbey and a reporter to the site and the story, including Ed’s comments, appeared in the July 6, 1987 edition.

“Abbey,” the reporter noted, “consistently skeptical about the park management system, said he has observed that the Park Service has a difficult time admitting mistakes, and too often subscribes to the philosophy: ‘In order to save it, destroy it.’

“‘When in doubt, do nothing, Abbey advised in this case. ‘When there’s a doubt about it, leave it alone.’”

A REPRIEVE?

Finally, it appeared that the Park Service was listening. In late June 1987, I received another letter from Guraedy. He wrote, “We have received several letters…expressing concern about the proposed burn. We have decided to open an Environmental Assessment to public input and examination. We will mail (a copy) to those who have expressed an interest.”

The burn was delayed until at least October 1987. Near the end of the year, the Park Service released the assessment and it received a great deal of public comment and criticism. In fact, there were enough intelligent and well-conceived letters to the superintendent to impress one of the park’s resource specialists to call for an indefinite delay.

On July 5, 1988, Kate Kitchell, Resource Management Specialist sent a memo to Wickware and Guraedy. Kitchell wrote:

“Although we thought when the EA for this project was released that we had thought this proposal through completely, the criticism received from the public suggests otherwise. While we received several supportive comments…there was also some strong negative, but very constructive criticism that has led me to conclude that the proposed action should be postponed until we have better defined project objectives….Prior to moving forward, we must properly assess the impacts, actions necessary to mitigate impacts, and completely understand the manpower requirements for conducting the eradications and associated monitoring. I also think that we should be committed to publishing the results of this activity to move forward the state of the knowledge of tamarisk control in the southwest….Let us work together to respond and revise the project over the next year.”

Kitchell’s written comments, which she generously shared with me, were a refreshing break from the Park Service’s defensive and intractable past. Here was a trained park official, not only welcoming public scrutiny but actually proposing to modify park policy as a result. Her memo went on to identify seven areas of concern, all of them initially raised by the public, that she insisted must be resolved before any tamarisk eradication program moved forward at Arches National Park. We all breathed a sigh of relief—the Secret Spring was safe, at least for the time being. We hoped forever.

Almost two years passed. I’d started The Zephyr in early 1989 and devoted a lot of my time to other Grand County issues, especially the proposed Book Cliffs Highway proposal. I’d received word that the tamarisk project was on indefinite hold. But I also heard that Kitchell had left the Park Service and joined the Bureau of Land Management which worried me some. But surely her recommendations would be observed and followed.

AND THEN…THE END RUN

Then one day, in early 1990, I bumped into a Park Service friend from Canyonlands National Park. We reminisced about “the good old days” in the NPS for a while; then he said, “Too bad you lost your tamarisk battle…I think it’s stupid too.”

“What?” I asked. “What are you talking about?”

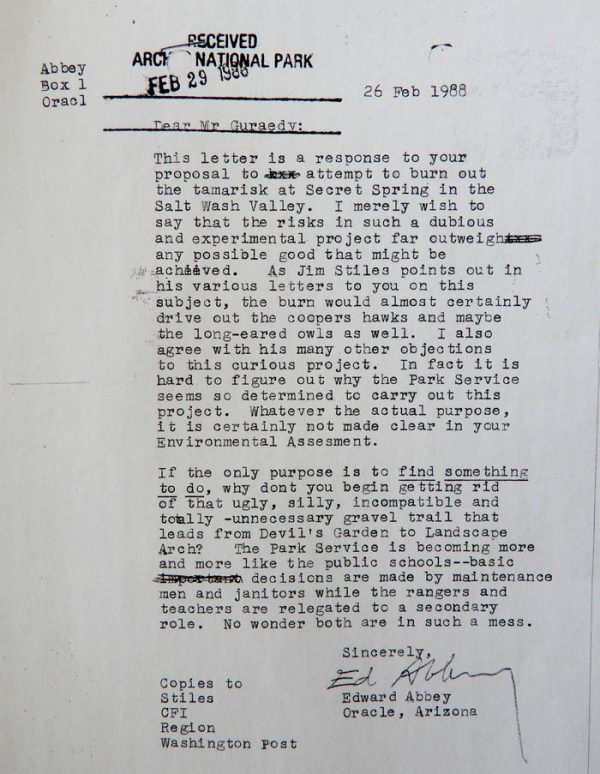

He told me the entire ugly story. The tamarisk had already been killed at my Secret Spring. I fired off a note to Supt. Guraedy. How could this have happened, I asked. How did they manage to proceed without even telling the scores of citizens who had written to express concerns? A few weeks later, I received this reply:

“I am writing to correct an oversight made in connection with the Environmental Assessment on the Salt Valley Wash Spring Tamarisk Control. This plan was abandoned when the Director prohibited prescribed fires of any type…We should have written, at that point, and advised you that the Environmental Assessment had been withdrawn…I regret that we simply overlooked the need to close out this Environmental Assessment.

“Nothing more was done on exotic species until Spring 1989. We still wanted to control tamarisk and wrote a Tamarisk Management Plan to accomplish this goal. The Plan was approved in May of 1989…We have been following this plan…at the Salt Valley Wash Spring (and) I am delighted to report that water is again coming from the Salt Valley Spring, in spite of the drought.

“We appreciate your interest in Arches National Park. We also regret that you were not informed about the fate of the Environmental Assessment…Hopefully, this will not discourage your participation in future projects.”

In other words, the Arches staff did an end-run on the public and all of us who had fought the plan for the past three years. Not once did the NPS notify any of us that they’d found a way to ignore us.

I protested the park’s action (The Zephyr was up and running now and I had a good rant) but it was a waste of time by now…the deed had been done. A former Canyonlands National Park Resource Management Specialist wrote a painfully long defense of NPS tamarisk control efforts in the July 1990 Zephyr. “Sorry the NPS did not inform you or the public,” he explained, “but glad to hear they are doing the work. That spring could be greatly improved by the removal of the tamarisk.”

It became clear that the park’s main justification and defense for the project in Salt Valley was its insistence it could “restore” the spring. There was an assumption by that “specialist” and others to follow him that in the wake of the tamarisk removal, the area would become a reborn and magnificent riparian wetland—a marsh of sorts—teeming with wildlife. (Hope springs eternal in a resource manager, driven by an unwavering assumption).

I was worn out by the whole debacle. It took me another year to make the journey to the “Secret Spring” to see the results. I was stunned.

The Secret Spring and environs looked like a disaster area. NPS crews had cut and poisoned hundreds of mature trees, leaving large spikes of dead tamarisk trunks behind. Then, they piled the dead wood into massive slash piles with the plan to burn them. It took years for the park crews to eliminate all the piles.

I looked for the spring, for signs of a wetland, but I could find nothing. The sandy wash was damp, but there was no standing water to be found. The Secret Spring was gone…

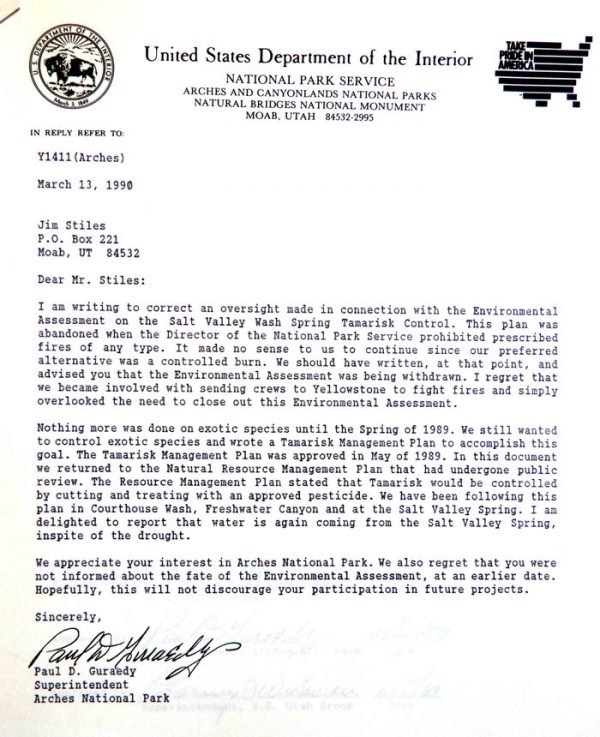

In the next Zephyr I wrote of my recent visit to the spring and the park’s efforts to remove the tamarisk. I got a quick written rebuke from the ranger at Arches who was now the “lead eradicator.” He insisted there had been standing water at the site the previous summer and still believed that their cut, poison and burn efforts would “restore the spring site.” He wrote, “…an established spring will benefit the wildlife and may well allow the reintroduction of pronghorn antelope, which previously occupied the area.”

Implying what? That the pronghorn left because of the tamarisk, and would now come back?

But despite his claims, the standing water was nowhere to be found. I did wonder about the spring’s fate–what happened? It is true that tamarisk can suck up a lot of water and I could at least see, in theory, why the NPS may have entertained some hope that it could increase the volume of water. But they should have studied the area more thoroughly–maybe bring in a hydrologist, who understands subterranean water flows and the corresponding geology.

I’m just a layman, but I tried to grasp what had happened and this is the best explanation I could muster…

The small pool wasn’t located in a side canyon; it was situated in the middle of Salt Valley Wash. Upstream from the tamarisk, the wash looked like any other desert drainage–dry, wide, sandy in places, and rocky in others. But when the wash met the tamarisk, the landscape changed. If nothing else, tamarisk controls erosion and stabilizes watercourse banks; in that respect, the tammies had done their job well. Despite flash floods, the nature of the wash here didn’t change. It was woody, shady and well-defined. Year after year, the pool survived.

But without the tamarisk, the next flood scoured the previously stabilized stretch of Salt Valley Wash, carried tons of sediment with it, and altered the stream bed so drastically that water now failed to reach the surface. My guess is the water is still down there, but buried under several feet of rock and silt. I left disheartened and angry; all I could do was hope that time and nature would correct this and that water would flow again at the Secret Spring.

In 2004, a full decade later, I made another trip; nothing had changed. The pool never came back. The wash was bone dry. I could find no sign of the Cooper’s Hawk nest that was once such a familiar sight in the cottonwood tree adjacent to the pool. Huge piles of slash–cut tamarisk trees—still covered the ground near the wash, fourteen years after the project was initiated. Russian Thistle, another exotic, flourished in many locations near the burn area. The only encouraging sight was the cottonwoods, which had survived, though they had certainly not multiplied and grown in numbers once predicted by the Park Service.

And this time, I didn’t hear a word from Arches National Park. In the 15 years since the eradication project had been initiated at the Salt Valley site, it was obvious by now, the pool wasn’t coming back. The marshy wetland predicted by the resource management crew never happened.

Over the next decade, I returned several times. But not once did I see standing water.

In 2015, I was met by a once familiar sight. New tamarisk was sprouting all along the watercourse downstream from the dry spring site. It had been 25 years since their eradication program had started and now, here was a new crop of the loathed and maligned plant, making yet another comeback.

ENTER THE BEETLE

In Response to The Zephyr’s 2004 article about NPS efforts to eradicate tamarisk, we received some feedback from Tom Dudley, then an Associate Research Professor of Natural Resource & Environmental Science at the University of Nevada, Reno. Dudley wanted to share his views on a new approach to tamarisk control. He wrote:

We’ve been working with this beetle (Diorhabda elongata) for many years, and have been able to show that it’s extremely specific to only feeding on tamarisk and nothing else in the wild (or crops either), and it simply dies when it runs out of tamarisk to eat.

… I don’t know why someone would be scared as hell by this, but I suspect that more information would reduce the fear factor… It’s frustrating when one is confronted by public animosity and fear regarding something that many of us have dedicated much of our lives to.

At the Millennium, scientists like Dudley prevailed, despite concerns from other scientists and environmentalists that the beetle could create new problems of its own. In 2001, the U.S. Department of Agriculture allowed the release of the beetle in Utah, Colorado, Nevada, Wyoming, and California. In 2003, the USDA extended the experiment to Montana, Oregon, and New Mexico. The beetles began munching their way through the tamarisk.

Some environmentalists feared that the beetle might encroach and destroy the habitat of the Willow Flycatcher, an endangered species that had adapted to the tamarisk thickets and used them as nesting and hunting areas. The USDA promised to keep the beetles at least 200 miles from flycatcher habitat.

But the beetle adapted too. It was assumed the tamarisk eater couldn’t survive at latitudes below the 38th parallel. But the beetle proved to be exceptionally flexible. Dr. Dudley called it “one of the clearest cases of rapid evolution.”

But others were worried. In 2009, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit against the USDA for failing to protect the flycatcher. Subsequently, the agency decided to “to rethink the biocontrol program in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In 2010, the USDA formally banned the release or interstate transport of the Diorahadba beetle in 13 western states, under the threat of stiff penalties imposed by the Endangered Species Act.”

But for some the damage was done. Dr. Robin Silver of the CBD noted, “If they move down the Colorado, into central Arizona, then we’re going to have the extinction of the flycatcher,” He told Tearrain.org, that the flycatchers “are incredibly faithful to their birthplace. If the trees disappear, the songbirds will go with them. Hanging in this delicate balance, the remaining willow flycatchers continue building their nests in whatever trees they can find.”

(NOTE: We’ve barely scratched the subject in this short article. To read an excellent and comprehensive history of the tamarisk beetle project, check out this story, “The Thirsty Tree,” by Melissa Sevigny. )

SEARCHING FOR AN ALLY…MATT CHEW & Company

I’ve never been an advocate for tamarisk, and in fact, I once wrote that the prolific exotic was the only plant that ever exasperated me so thoroughly that I wanted to hit it. Getting caught in a tammy thicket on a hot summer day is a nightmare I try to avoid. But the war against tamarisk has always seemed to me like an extremely expensive and utterly futile gesture. A make-work project at best. But such suggestions tended to light fuses among the NPS eradication aficionados. Though I was no longer employed by the agency, I still had NPS friends who kept me informed of the inner office skuttlebutt. I heard that the Park Hierarchy thought I’d gone mad. Or was just trying to be more annoying than usual. After my first Zephyr tamarisk report in 1990, I received a massive 3000 word screed from one of the parks’ most aggressive tamarisk eradicators. We printed it all, without edits, in the next issue. But as I came to expect, the criticisms were more personal than factual. In fact, the rant began like this:

“It is great to see, Jim, that you still have a dislike for government agencies. Some things will never change.”

The author (and I’ll keep him anonymous for now) was particularly sensitive about an ill-fated tamarisk “controlled burn” that he supervised in the mid-80s. By his own account, the project was a complete debacle. Even his fellow rangers turned on him, and as the author recounted, “Tempers flared.” After recruiting some river rangers to help cut the tamarisk with chainsaws, it became apparent in the 100 degree heat that he had aggravated his co-workers to the point he feared for his life.

He wrote, “I had to start talking fast. ‘Well guys,’ I said. ‘Maybe this is not going to work, maybe this is not such a good idea.'”

And yet, though he abandoned the project, the writer closed his long essay with this warning: “If I ever have a chance to work in an area with tamarisk again, I will still initiate a program to burn and cut tamarisk.” And he offered this last bewildering admonishment. “Jim, there will always be critics like yourself…on any proposal, and that is great. But I always remember the story of the man that was once riding the back of a donkey and having people criticize him because he was too big. He finally ended up carrying the donkey on his back.”

I could never tell if his fable was intended for me or for himself.

(The 1990 article preceded the digital age and so we don’t have a link to it, but for entertainment purposes, we may someday transcribe and post it)

At the time, most of the scientific community supported tamarisk eradication and there were plenty of stories about the Evil Weed and its impact on water supplies in the arid Southwest. Like the hopes that the Arches staff had for the Secret Spring, it seemed as if many in the scientific community thought tamarisk elimination could be a miracle cure for drought…that its eradication could raise lake levels and increase river flows. As if it might save us all from water shortages into the future!

No one at the time stopped to consider what might happen IF a surplus of river flow did appear…would the newfound H2O make its way to the Gulf of California and restore water-deprived riparian areas? OR…would it provide the needed water resource for even more growth and development in unquenchable cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix? The honest answer was clear even then; the denials last to this very day.

But then, about a decade ago, I heard from a professor at the Arizona State University. His name was Matt Chew and he was a breath of fresh air—of cleansing common sense. Here is the way ASU describes him…

Dubbed a ‘gadfly of invasion biology’ by Scientific American, Matt Chew is known for critiquing ecology’s overreliance on societal metaphors and conservationists’ misapplication of notions like ‘nativeness’. A creature of the American southwest, Dr. Chew was raised in Arizona, earned two natural resources degrees at Colorado State University, then returned to Phoenix to consult for the Defense Department, Bureau of Indian Affairs and other government clients. As statewide Natural Resources Planner for Arizona State Parks, he coordinated their Natural Areas Program, researched wildlife issues, and served on interagency committees—one of which also included his future wife, plant ecologist Julie Stromberg. With her encouragement, he abandoned government work to earn a biology Ph.D. based entirely on historical research.

Remaining at Arizona State University, Dr. Chew conducts a field course in ‘novel ecosystems,’ lectures in ‘history of biology’ and ‘biology and society’, and works with postgraduate students. He was awarded an Oxford research fellowship in 2014. His articles in “Nature,” “Science” and niche publications in history and conservation have been cited in over 200 different journals. Drs. Chew and Stromberg live in a historic farmhouse on irrigated land, where they rescue dogs, garden to attract wildlife and buy more books than they can read.

Chew’s rational approach to the issue of exotic eradication was and is a breath of fresh air for me. His groundbreaking “The Monstering of Tamarisk: How Scientists Made a Plant into a Problem,” in 2009, offered these conclusions…

From 1877 to 1953 American academic botanists and ecologists displayed mostly mild interest and curiosity regarding Tamarix species, without really making them a focus of research. During the same period, horticulturists uniformly recommended tamarisks as drought and salt-tolerant ornamentals. But in less than a decade, from the inception of the Pecos River Joint Investigation in 1938 to the completion of the Lower Safford Valley research project in 1944, the opinions of scientists and scientifically trained natural resource managers toward tamarisks changed drastically. Government experts (often from or affiliated with USDA units) had imported, recommended, distributed and planted tamarisks well into the Dust Bowl era. After seeing the naturalized stands at Lake McMillan, other government experts led by USGS hydrologists declared the plants to be worse than useless.

Shrubs once extolled for erosion and sedimentation control became machine-like monsters pumping away scarce western water. Hard on the heels of that assessment came a further redefining moment, the wartime recasting of tamarisks in the Safford Valley as alien aggressors. By 1950 a permanent interagency bureaucracy had sprung up, focusing primarily on slaying the beast rather than demonstrating actual water salvage. It began to propagate the legend, as well as a few myths, that would keep its members busily cutting, bulldozing, spraying and reporting progress in terms of vegetation killed for another 20 years.

During the period described, naturalized tamarisk had little or no discernable public constituency, and little prospect of gaining one. Few who cultivated or advocated planting tamarisks would likewise have advocated the plants’ unrestrained self-propagation. By the same token, there was little likelihood that a popular sentiment would develop against naturalized tamarisk. The rural West was more sparsely populated than the rural South. Relatively few private citizens encountered tamarisk on private lands the way Southerners faced kudzu. The monstering of tamarisk required the kinds of organization and impetus that only the federal government could provide in that era.

Lacking candid insider accounts, it is rarely obvious whether scientist-bureaucrats actually support the aims of the programs they are assigned to carry out, and thus whether their rhetoric represents principled endorsement, sincere conviction, careerist pragmatism or cynical manipulation. Tamarisk was a denizen of major, mostly federal (or federalized) water projects. The physiology and ecology of the plants was examined almost entirely through the lenses of hydrogeology and water politics. Tamarisk was a convenient scapegoat for the complex problems encountered by government water managers, be they true believers in the monster or otherwise. Even so, it does not seem to have mattered strongly to the principals whether suppressing tamarisk ever made more actual ‘‘wet water’’ available. They could demonstrate productivity in acres of vegetation laid waste, again and again, while suppressing or simply ignoring the substantial doubts lingering over their theories, methods, and mandate. Monstering tamarisk was far from a superstitious exercise. It was an effective way to perpetuate a program.

By 2015, even Smithsonian magazine was acknowledging that “the (tamarisk) story may be more complicated.”

In the Smithsonian article, Chew essentially took a page out of the comic strip Pogo, the character who once noted, “We have met the enemy and they is US.” Chew pointed out that for decades, we humans have been altering the environment in ways that have made it easier for tamarisk to take root and flourish. He told Smithsonian, “The Reclamation era of dams has pulled the rug out from under native vegetation.” Tamarisk, he observed, has the unique ability to survive the dry spells. Smithsonian reported that, “Chew feels the backlash against the plant has replaced proper science, which is no longer being used to back up the contention of undue water use and crowding out of other plants and trees.”

Calling the eradicators “tammy whackers,” Chew complained that “we have created an environment for the tamarisk.” Now he sees the same government entities spending exorbitant amounts of money and time trying to destroy their own Green Frankensten.

In the Smithsonian article, other scientists, like Edward Glenn from the University of Arizona, and Juliet Stromberg, a plant ecologist at ASU, offered similar perspectives, challenging the conventional wisdom of the “tammy whackers.”

And finally, the article noted that even environmental groups have considered the more complicated aspects of the tamarisk debate:

Although the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club isn’t currently working on tamarisk, the group is sensitive to the complications of the issue. “We have removed some in the Rio Salado, some on the Verde and quite a lot on the Agua Fria” rivers, says Sandy Bahr, chapter director. “We would like to see native endemic vegetation restored, especially cottonwoods and willows, but understand that we have to have more natural flow regimes to support those trees.

And yet, at Arches, the National Park Service recruited Sierra Club volunteers to participate in some of its eradication efforts, even at the Lower Salt Valley Wash site. Apparently, even the Sierra Club is having second thoughts.

(Again, what I’m offering here is a very brief synopsis…take the time to read the Smithsonian article in full…)

* * *

Thinking back to my lost Secret Spring, Dr. Glenn’s own observations helped confirm my worst fears for its sudden disappearance. From the Smithsonian story:

Further complicating the issue, after tamarisk was removed from the Virgin River in Utah, a 2005 flood showed what happens when the plant is no longer there to control erosion. “A whole bunch of sediment moved downstream,” Glenn says.

That was my conclusion at the Salt Valley site. For decades, the tamarisk had controlled the banks of Salt Valley Wash during those heavy desert flash floods. The stabilization had probably allowed the cottonwoods to take root to begin with. And it had allowed for this small pool of water, this tiny oasis, to survive in its shade. But once the tamarisk was removed, nothing could retard the flow, the wash in that section of the valley was transformed, and the seepage was buried under the sediment.

Recently, as I prepared this story, I contacted the staff at Arches National Park, to see if the “Secret Spring” site is still being managed. Lee Ferguson directed me to the park’s ecologist and vegetation program manager, Liz Bellanger. Liz was very helpful and answered all my questions. She explained that the Salt Valley Spring “is not a site we’re currently maintaining for tamarisk removal (looks like the last treatments were in 2001-2003), however it’s a site we do monitor every few years for early detection of other exotic species. Riparian corridors (particularly those frequented by humans or livestock) are particularly susceptible to exotic species invasion, and we work to eradicate new introductions before the plants multiply out of control.” Bellanger added that, the NPS “still uses Garlon in our cut stump treatments … (and) slash was burned in huge piles.”

Bellanger wasn’t sold on my analysis of the spring’s demise. She wrote, “I’m not convinced it’s the reason why there’s no longer surface water at ‘Secret Spring.’ Climate change is most certainly a contributing factor, and we are monitoring a number of springs in (Canyonlands, Arches, and Natural Bridges) for water flow and other parameters.” Their studies showed a drop in standing water at other locations as well, but whether they vanished as suddenly and as permanently as the “Secret Spring” remains up for discussion.

But Liz Bellanger agreed that:

“I share your concern that well-intentioned management actions can have unforeseen negative consequences. One good example of that with regards to the tamarisk beetle is fuels buildup over the past decade from dead/dying tamarisk, creating tinderbox conditions in some riparian areas (though coyote willow is actively filling in many places). As you probably know, some intense wildfires occurred on Green River bottoms in Canyonlands in recent years, destroying ‘legacy’ cottonwood stands that sprouted long before all the dams and diversions upstream.”

I couldn’t help but think of her predecessor from long ago and his very long Zephyr “tamarisk defense” article I mentioned earlier. In 1990, he had insisted that burning tamarisk should and would continue. But he added, “Tamarisk burns, and where there are tamarisk and people, there will be fires. The important point is to assure that the cottonwoods are not destroyed.” (emphasis added).

An ironic epitaph.

* * *

Tonya and I returned to the site of the Secret Spring last month, almost 45 years after my first visit. The oldest of the cottonwood trees, the tree that was once home to the Cooper’s Hawks, is starting to show its age. It must be pushing 100. Thankfully, there are younger cottonwoods nearby to keep the stand alive. Down there beneath the sands, somewhere, the water is still nourishing the roots of these poplars. The skeletal remains of the old growth tamarisk trees still stubbornly cling to the banks along the stream bed. And the old iron cowboy tank and wooden trough are still there too, though they continue to deteriorate and yield to the passage of time.

When I first found the “Secret Spring” and the stand of tamarisk and cottonwoods, the little oasis was barely known to anyone. When the Park Service decided to target the area for its eradication program, all that changed. It wasn’t a result of public demand. It was the victim of an experiment.

According to NPS records I obtained in my 2004 Freedom of Information Act request, the NPS devoted thousands of hours, committed tens of thousands of dollars, and applied scores of gallons of toxic chemicals, all to “restore” a part of the park’s ecosystem that the agency believed needed improving. A place that nobody knew.

Now, almost two decades after all that intense scrutiny and hands-on “habitat improvement,” my old lost oasis doesn’t feel the same. And yet, unlike other transformed parts of the park that have been “discovered” and promoted, and plastered all over social media, and consequently overrun with an excess of human enthusiasm, the fate of my Secret Spring was decided by a little noticed bureaucratic decision, decades ago, that for most has long been forgotten.

During my decade at Arches, I explored almost every square inch of Arches. There came a time when I avoided the “crowd pleaser” features, the iconic “jewels” of the park. Every week, back then, my schedule gave me two days that said only “backcountry” on it. What did that really mean? Could he be more specific? My first boss, Chief Ranger Jerry Epperson, gave me some good advice.

He said, “Get in your jeep. Drive a couple miles. Randomly stop the car, pull over, get out, pick a direction, and start walking. Believe me…you’ll find something.” He was almost always right. All these years later, when I employ that same technique, no matter where I am, I think of Jerry. And I think of fellow ranger Kay Forsythe, who then added, “And don’t tell anybody.”

In 2020, it’s not a preferred way of exploring. Not enough data. No social media cachet. But After decades, for that very reason, I still find so much of the land untouched.. Because it was never exploited, it never received the vital cachet No facebook likes, no selfies. No crowds. I hope those remaining magical places can stay like that–anonymous and unknown.

But my “Lost Secret Spring.” It was there, it was briefly “discovered,” then altered, impaired, and now it’s gone. But at least it’s quiet…If I’m the one and only soul to mourn its passing, then maybe that’s the way it should be.

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Click Here to read the previous installments of Ranger Stiles’ Wildlife Observation Notes…

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Clearly a result of not looking a the situation of Secret Spring holistically. One has to look at the big picture of removing invasives in a setting and not just removing invasives for the sake of just that. What is the goal? If there will be more disturbance to the site and harm to native vegetation and wildlife then a more cautious approach is warranted.

The NPS obviously wanted to use less labor by burning the site, which it ultimately did not do. But as Jim and others in the article pointed out, the banks of the spring were destabilized and more erosion was created by tamarisk removal not to mention really total habitat destruction. It was a sad story to read about an experiment gone awry.

Government agencies are not always right in their assessment in projects they want to undertake so the public must be vigilant but only if they are kept aware. That is the difficult part is knowing about projects.

Jim, I read your article with great interest. Finding a secret spring and then to see it discovered and destroyed by others has to be gut wrenching and heart hurting. Your views on Tamarisk and links to more details (which I have yet to read) mirror my own observations as I explore the canyons of San Juan County, Utah. Tamarisk seems to be temporally dying out from the beetle attacks only to come back again. Over and over again I see new growth of Tamarisk.

Thanks for your writing. The time spans and chronological order of your writing is especially valuable for now and for the future. In other words your devotion to details and photos gives substance to what would other wise be opinion. It helps that you have been blessed with a long life, with good health and a strong awareness of what is going on around you.

An excellent assessment of the entire tamarisk ‘problem’, proving that nothing in the environment is simple or cut-and-dried (except for a burnt tamarisk perhaps). Brings to mind the reflection that everything in the world is hitched together and if you remove any part of it, you can expect unexpected consequences. Was that John Muir or Aldo Leopold? Maybe both.

Perhaps the Secret Spring will someday reemerge for our grandchildren to discover anew. Nature has its own timetable.