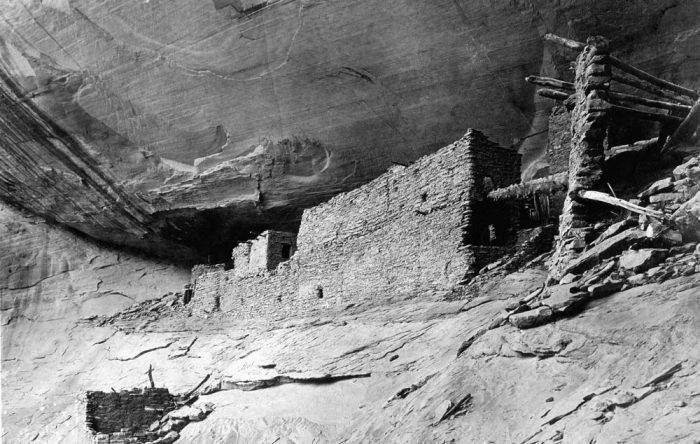

“Whereas, a number of prehistoric cliff dwellings and pueblo ruins, situated within the Navajo Indian Reservation, Arizona, and which are new to science and wholly unexplored, and because of their isolation and size are of the very greatest ethnological, scientific and educational interest, and it appears that the public interest would be promoted by reserving these extraordinary ruins of an unknown people, with as much land as may be necessary for the proper protection thereof…“

— President William Howard Taft, Proclamation 873, Establishment of Navajo National Monument, 1909

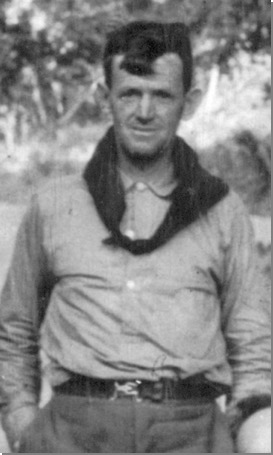

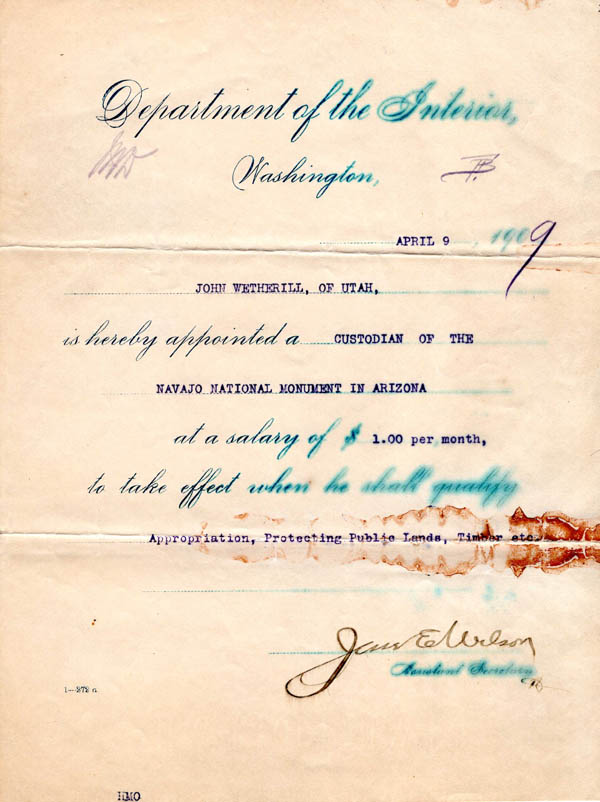

“I will gladly look out for the ruins without pay untill [sic] such a time as some regular superintendent can be appointed,” John Wetherill wrote U. S. General Land Office surveyor William Boone Douglass on March 7, 1909.

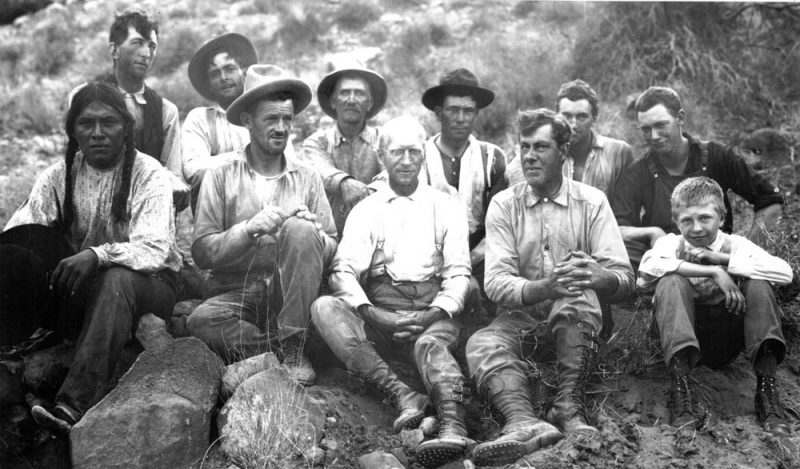

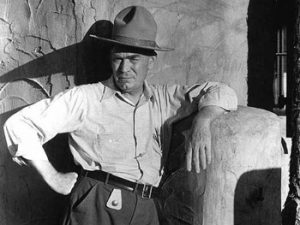

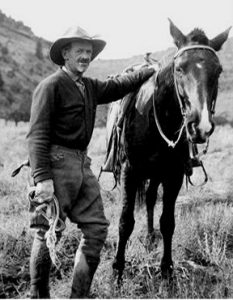

Douglass was promoting the idea of a national monument to preserve some spectacular archaeological treasures in the Navajo country of northeastern Arizona, but the authorities in Washington, D. C. would not consider such a proposal unless a local caretaker could be appointed to monitor and protect the sites. Wetherill and his family had long been advocates for archaeological preservation (see my article, “‘We are Particular to Preserve,’ The Wetherills’ Passion to Protect the Southwest’s Past” in the December/January 2020 Canyon Country Zephyr), he lived nearby, and he was willing to add this new role to his busy schedule of running a pioneer trading post, hosting visitors, outfitting and guiding pack trips into the outback, and searching for ever more wonders in the wild reaches of the region.

Little could he have anticipated the trials, travails, adventures, and memories that his new assignment would bring into his life or the length of time it would take the authorities to appoint a “regular superintendent”.

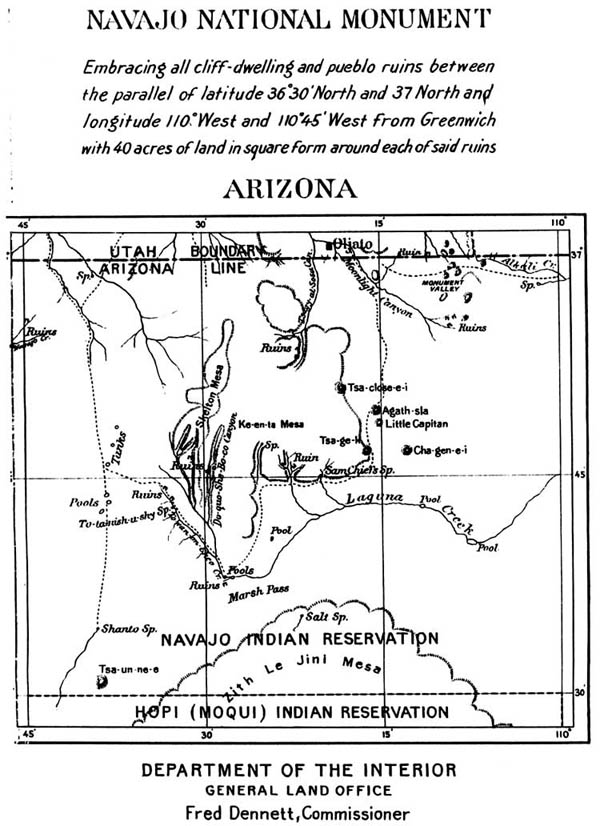

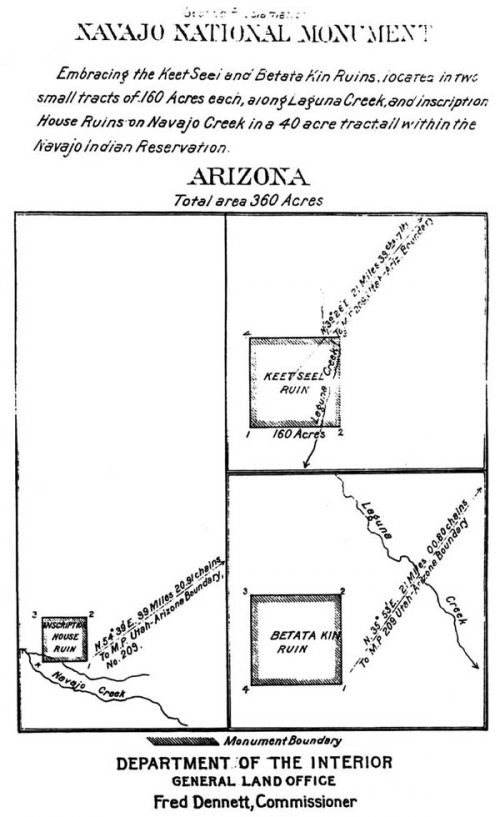

Although Douglass had not personally seen any of the significant dwellings in the area, he had heard about some of them, including the beautiful and massive Keet Seel cliff-village in a tributary of Tsegi Canyon. He thought that science could best be served by taking a conservative approach and including a large swath in the monument designation. On March 20, 1909, President Taft issued Proclamation No. 873 establishing Navajo National Monument. Based on Douglass’s recommendations, it encompassed a substantial area containing an undetermined inventory of archaeological sites.

On April 9, the General Land Office issued an appointment document designating John Wetherill as custodian of the new monument “at a salary of $1.00 per month.” His duties were general supervision, submission of a monthly report, and notification to a policing authority of any “trespass or violations” in order to “prevent trespass, injury or destruction of relics or the extraction or carrying away of gatherings.” The government promised to provide printed notices, which Wetherill was to post “upon conspicuous places upon the dwellings or ruins and adjacent to trails leading to, within, and from said monument.” Given the fact that there are hundreds of archaeological sites within the area of the proclamation, most of which were unsurveyed and without trails, Wetherill must have wondered what the far-off authorities were thinking.

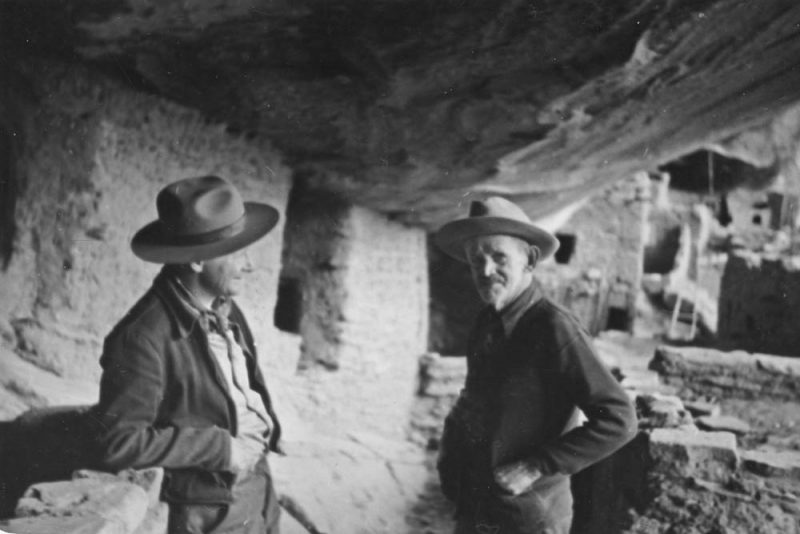

In July, Wetherill led Professor Byron Cummings of the University of Utah and some of his students to a tributary of Navajo Canyon, some distance west of the monument boundary, to visit another cliff dwelling that was then known as Adobe House. A cryptic inscription found on a wall by Cummings’s son, Malcolm, and Wetherill’s daughter, Georgia, was interpreted as of Spanish origin, and Cummings began calling the site Inscription House.

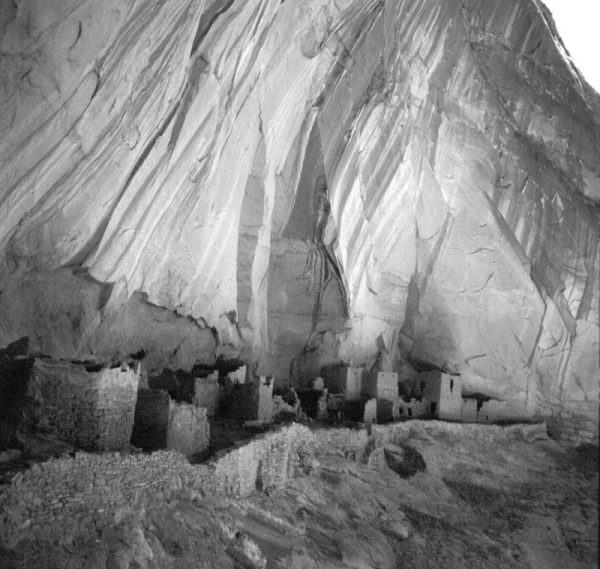

On the way back to the Wetherills’ home at Oljato, the group stopped in Tsegi Canyon to visit with a Navajo woman, Mrs. Nede Cloey (Nii’ditt’oii). She told them of another large dwelling in a side canyon. “We wanted to visit the ruin at the time,” John recalled, “but our horses were so tired and weak that we were unable to go at that time.” A few weeks later, on August 9, John was back in the canyon with the Cummings party, and they enlisted a Navajo man, Clatsozen Benully, to lead them to the site. That was the first recorded visit of outsiders to the beautiful cliff-dwelling they called Betatakin.

On March 14, 1912, Taft reduced the size of the monument via Proclamation No. 1186 to a much more manageable total of 360 acres consisting of three parcels surrounding the cliff dwellings of Keet Seel, Betatakin, and Inscription House. That dramatically increased the odds that Wetherill could successfully perform his job duties, although the demands on him would still be onerous.

The preparation of monthly reports was not something Wetherill had bargained for, and, fortunately for him, no one in the General Land Office ever requested one. Nor did he expect to receive a “salary” of $1 per month, and that part of his charter went unfulfilled, as well. He did have the benefit of charging visitors a fee to guide them on horseback and camping trips to the dwellings. “Here are the prices I paid, and they are the regular rates,” recorded an early visitor, writer George Wharton James: “Each pack or saddle horse in the party, $1.50 per day; guide and his horse, $8.00 per day; if the party is large enough to require it a helper must be engaged at an extra $3.50 per day. In addition, the traveler pays for all provisions for himself and guides, and all feed needed for the animals.”

Besides his monetary earnings, Wetherill had the reward of observing the salubrious effect of the experience on some of the visitors. For example, James found his excursion to the cliff dwellings particularly thought-provoking: “…as I rolled into my blankets that night, my feet to the camp-fire, I could not help asking myself many direct and searching questions as to how much farther advanced in real life we are today than the ancient Cliff-dweller. Are we healthier, happier, kinder, more useful? For, after all, what is advancement in civilization if it leaves out these important phases of life?”

About fifty miles northwest of Betatakin, at the end of a rugged horse trail, is the majestic and incomparable Rainbow Natural Bridge. President Taft proclaimed it a national monument on June 30, 1910, but the General Land Office did not designate a custodian to look after it. Wetherill unofficially took over that responsibility, keeping a record of its visitors and improving and maintaining the trail. Some of the visitors to Navajo National Monument asked him to continue their journeys on to Rainbow Bridge—a trek that could take a week or more. Notable adventurers in 1913 were the author, Zane Grey, and the former president, Theodore Roosevelt (for the Roosevelt trip, see my article, “The President Slept Here: Theodore Roosevelt’s 1913 Visit to Kayenta and Beyond” in the August/September 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr).

One of Wetherill’s first challenges as custodian of Navajo National Monument was mediating a disagreement between its sponsor, government surveyor William Boone Douglass, and University of Utah professor Byron Cummings. In 1907, Cummings had begun taking students on summer outings to the Four Corners region to introduce them to archaeology. From his perspective, he was doing so in a responsible and professional manner. Wetherill and Cummings were friends and had a great deal of respect for one another. Even though both Douglass and Cummings had been leaders on the 1909 expedition that brought to the world’s attention the existence of Rainbow Bridge, Douglass disliked Cummings, calling his archaeological party a “pseudo-scientific expedition”.

Douglass was a proponent of the popular progressive belief that Native Americans are relics of an earlier and inferior stage of human social evolution, declaring that “…the human race passes through all stages of development in its rise from the paleolithic age to one of highest culture, and that in the study of these lowly types we learn the history of us all.” Pristine archaeological sites were of value, Douglass believed, because they provided scientists with opportunities to better understand the ancient ways of the distant ancestors of civilized people. One of his motivations in recommending establishment of the monument was to prevent people like Cummings from digging in any of the protected dwellings and destroying the evidence that the more enlightened researchers were looking for. He advocated that the privilege of doing any archaeological work within the monument be reserved only to the Smithsonian Institution.

So, in the summer of 1909, when Douglass heard that the Cummings party was conducting excavations within the monument, he became irate and telegraphed the authorities in Washington, demanding that the work be put to a stop. On August 9, Assistant Commissioner Samuel V. Proudfit of the General Land Office wrote Wetherill, asking him about the reported transgression. Wetherill replied: “I beg to state that there is no one excavating on the Navajo National Monument except Prof. Cummings and party, and they are doing so under a permit issued to Edgar L. Hewett, Director of the Archaeological Institute of America, by the First Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Interior, Frank Pierce.” Douglass was unable to prevent Cummings from continuing his work. Although Douglass continued feuding with Cummings, Wetherill was able to maintain cordial relationships with both men. Ironically, one of Cummings’s students, Neil Judd, was chosen by the Smithsonian to lead an excavation and stabilization project at Betatakin in 1917.

In the summer of 1916, the General Land Office sent W. J. Lewis to the monument to assess its condition. Wetherill told him that about fifty people had visited Betatakin and Keet Seel in the previous year, but he knew of none who had gone to Inscription House. Lewis made several recommendations to improve access and signage for visitors, and he commented on the impracticality of Wetherill providing adequate protection for the cliff dwellings. “Mr. Wetherill is a man of more than ordinary intelligence and takes a very deep interest in the ancient ruins in all that part of the country and their preservation,” Lewis reported, “…but he informed me that such act of vandalism as have come within his notice, such as the scratching of inscriptions on the walls, etc. have served to make him realize his powerlessness to prevent same.” Lewis also noted that the General Land Office had never paid Wetherill his $1 per month salary.

On August 25, 1916 Congress created the National Park Service to which Wetherill’s responsibilities were transferred. In their first published staff roster, they listed John as one of only thirty-two staff members nationwide. In early 1917, John notified headquarters that he was not receiving his pay. “…you have not filed claim therefor, which accounts for non-payment,” the acting superintendent advised. In 1918, the director sent John a voucher. “Please sign the voucher and return the same, upon receipt of which, prompt payment will be made”.

At about that time, Wetherill was instructed by headquarters to send in a report for the previous year. “It is desired that as full a statement as practicable be made of the number of visitors to the monument, the number of animals, if any, grazed therein, and the improvements effected or begun, such as roads, trails, etc., with a general review of any other facts or events of interest, concerning the monument.” John’s meager compensation would not begin to cover the time he would need to spend producing such a document, but the reports did give him an opportunity voice his ideas and concerns to the upper echelons of Park Service management. He used them to advocate for protection of Canyon de Chelly and Monument Valley, for example.

As the years rolled on, the demands involved with producing the reports ever increased. In 1919, headquarters instructed Wetherill to “Kindly include in the report all matters of special interest that have transpired during the year, laying special emphasis on all matters relating to wild animals, birds, forests and wild flowers, and the work of the Service through yourself as its representative in encouraging the study and enjoyment of these and any other natural features.” In 1921, he was instructed that his report “should be on paper 8 x 12½ inches, double or triple spaced, using single spacing only for quoted matter that includes several lines. Leave a margin of at least an inch at the top of the page, an inch at the left, and at least half an inch at the bottom. Indent paragraphs ten spaces.” A few months later, he was advised that “The Service is desirous of having of record an inventory from each office showing what typewriters are in the field, and the information desired is, trade name of machine, length of carriage, and trade number.” The far-off bureaucrats seemed not to be aware that Navajo National Monument had no office, and the government had never provided its custodian with a typewriter.

The 1920s brought increased visitation to Navajo National Monument. In 1922, for the first time, Wetherill reported more than one hundred people had visited the dwellings during the previous year. His job was complicated by the improvement of an old wagon road from the southwest that now made automobile travel possible to mouth of Tsegi Canyon. From there, visitors could hike up the canyon to Betatakin and Keet Seel without Wetherill’s knowledge. Some of them engaged in various act of vandalism, such as leaving graffiti or digging around for relics.

In 1924, the Park Service created a new subsidiary, the Southwestern National Monuments Office in southern Arizona. They appointed Frank Pinkley, who had served as custodian of the Casa Grande pueblo since 1902, as superintendent of fourteen national monuments in the Southwest, including Navajo and Rainbow Bridge. From then on, Wetherill was to report to him, rather than to the authorities in Washington. Pinkley became fondly known to his employees as “The Boss”, and he and John Wetherill came to respect and admire one another.

In 1929, Wetherill’s twenty-year anniversary at Navajo National Monument came and went with no hint that the Park Service intended to relieve him of his duties and further protect the monument by hiring a full-time superintendent. He expressed to Pinkley the impossibility of handling the job on his own: “It is about time to take some care of our ruins here as every party who goes in without myself or one of my guides carries off relics of all kinds. They will be stripped of everything unless something is done. I cannot put in my full time without some recompense. We need camp houses. We need the trails made better. We need a building for a museum. We need an office. We need sign boards. We will have nothing to protect unless it is done soon.” Apparently, Pinkley was powerless to resolve Wetherill’s concerns.

In about 1932, Pinkley began requiring that his custodians send in monthly reports, which he published in a mimeographed periodical he called Southwestern Monuments Monthly Report. “It seems as if the ink is hardly dry on one report when it is time to send in another,” Wetherill later complained (a sentiment shared by his descendant with regard to Zephyr articles). To the Boss’s request for ideas to save money, Wetherill replied: “In regard to economizing on office material, if you do not return so many of our vouchers and ask for so many reports, we would save a lot.” Pinkley duly published Wetherill’s wisecracks in his periodical.

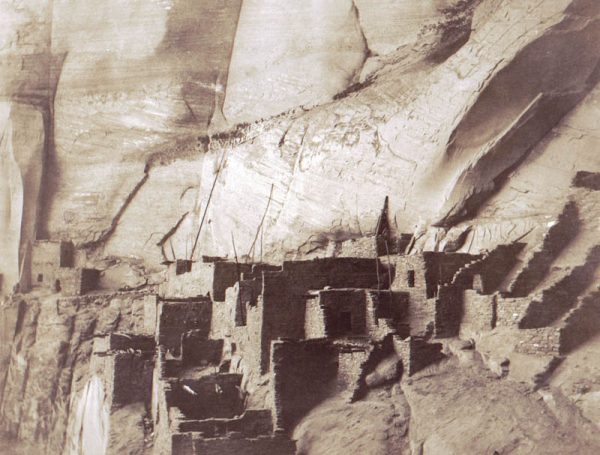

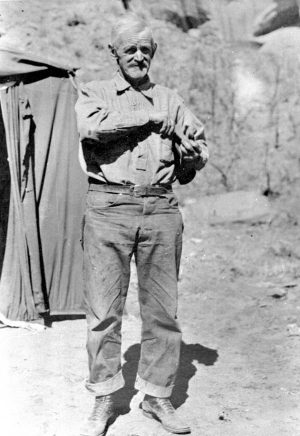

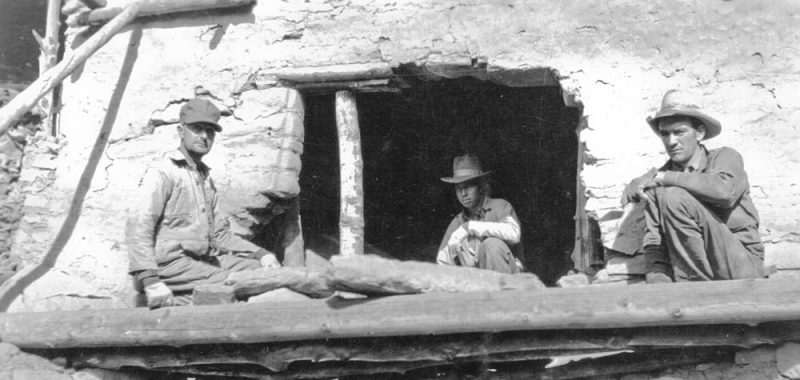

On New Year’s Day, 1934, Wetherill was camped with a crew of twenty-eight destitute men from Holbrook, Arizona at the mouth of Tsegi Canyon, preparing to lead them on the twelve-mile trek to Keet Seel. The men had been hired by the Civil Works Administration, a federal New Deal program to reduce depression-era poverty. Their task was to repair and stabilize Keet Seel, and Wetherill had been appointed as their superintendent. Since his Navajo friends had begun calling him Hosteen John (Hosteen being a Navajo title for a respected, older man), his team members used that title for him, as well. He enlisted his nephew, Milton Wetherill, to serve as foreman, and the government appointed Harvard-trained Irwin Hayden to serve as the project archaeologist.

Hosteen John requested authorization to pay the workers fifty cents per hour for forty hours of work per week. A few weeks later, a lone rider came into camp to relay the disturbing news that the CWA could only pay the men for fifteen hours of work per week. Wetherill was ordered to report to a meeting in distant Ash Fork, Arizona in a few days to discuss this situation. Hayden reported what happened next.

Hosteen John put it up to his crew: “What do you want to do, men? It looks as though we were through, but maybe not.” To a man, the outfit stuck: “We’ll stick, hours or no hours, pay or no pay, until you get back from Ash Fork.” Bill Young, head packer, said he would stay by John Wetherill to the end. Josh Young, another valued member of the party, said he would stay with John Wetherill even though a certain place notoriously hot might become completely sealed in ice! At least that is the gist of what he said….

Oh Yes! When Hosteen John returned with news of the 30 hour work week we all said; “Well, we knew John Wetherill would take care of us!”

Wetherill respected the workers, as well. “They all seem to like the work and the country and I want to repeat that never before have I had the pleasure of working with such a willing bunch of men,” he wrote.

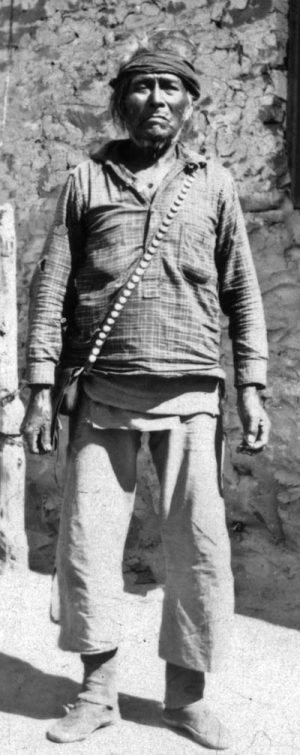

In April, Wetherill reported on the challenge of an intruder who came into the monument—a Navajo witch:

“He comes to camp nearly every day. He has a camp about three miles down the Canyon where he lives with his niece and her husband and child. They have a bunch of goats, about 150 in number. He was born at Bosque Redondo (Fort Sumner) while the Navajos were held prisoner there from ‘63 to ‘67. His father was a Mexican, thus his name Nocki (Mexican) and Yazzi (Little), or Nocki Yazzie (“Little Mexican”). In 1908 he claimed to be a witch and threatened to bewitch seven people, among whom was his mother. They tried to capture him, and did, but made the mistake of taking him to the trader’s store at Oljato where Mrs. Wetherill was and she worked with Nocki until he promised not to bewitch any more Indians. On the strength of his promise, the Indians turned him loose. He had been free only a couple of weeks when one of the seven he said he would not bewitch, died…. Since his return he has been accumulating a herd of goats. He goes to a Navajo and tells him if he does not give him a goat or a sheep he will bewitch him. They usually give him the worst they have. Three years ago he had about two hundred fifty head. To ride toward the bunch looked like riding into a bunch of horns, as fifty percent of his goats were very old. Most of the old goats are dead now on account of the two hard winters we have had. Now he has about one hundred fifty fairly good goats which he is herding, a part of the time, on the Navajo Monument.

Old Nede Cloey, (Fuzzy Face) who has been running cattle in Keet Zeel Canyon, is afraid to run him out as he is afraid he will bewitch some of his family….

In March, Boss Pinkley reported in his Monthly Report:

We wrote Hosteen John Wetherill saying we thought he ought to have a first aid kit and asking his opinion on it. Here is his reply:

“Send your first aid along if you think we need it. We have some cough syrup, Mercurochrome, Aspirin, Zinc Ointment, Liniment, Vick’s Salve, Iodine, Zinc Oxide, Adhesive Plaster, Plaster Paris Bandages, Gauze, and some more stuff that I don’t know how to spell. If the kit contains snake remedies, send it along as I think we could use it, though we have no snakes.”

“Just to keep the record straight on that snake bite outfit,” Pinkley interjected, “we are thinking of sending along a couple of snakes.”

After about four months on the job, the CWA crew disbanded. Their major contribution was reconstruction of a balcony/walkway connecting two sections of Keet Seel that had fallen away in the centuries since the cliff dwellers left. Hosteen John returned to his home in Kayenta and resumed his periodic visits to the monument.

Down canyon from Keet Seel, another public works project team constructed a new trail to enable descent of the cliff near Betatakin. Its purpose was to provide a route for Native American herders to take their livestock to water in the stream at the bottom of the canyon, but it created new threats to Betatakin and Keet Seel. Since there were no fences, the grazing animals could freely cross the monument boundaries, damage vegetation, and trample archaeological features. More seriously, outsiders coming from the southwest could now drive to the head of the trail, hike down to the dwellings, and, without the awareness of Wetherill, engage in uncontrolled vandalism.

In June 1934, Wetherill returned from a patrol of the monument with a disheartening report:

I have just returned from a trip to Kit Siel and Betatakin. Quite a few people have been here, including a large number of the Hiking Club of Flagstaff. It was rather discouraging to see the vandalism that has gone on since I was last there. At Betatakin vandals had taken off a large number of pottery sherds and all of the metates and manos that they could carry off. At Kit Siel they have spoiled a room that had been left after it had been cleaned out to show to the tourists, with the pots, pot rings and cedar bark rope in position. The rope and all the pot rings had been carried off and the lintel of the door of a side room removed. The trash of the room that had been used as filling was scattered over the floor of the exhibit room. Two of the potnecked Sipapu had been dug out by people thinking they had found pots. And much more destruction has been carried on that will develop after we have had a chance for further investigation. You’ll agree that this is enough to discourage anyone who is trying to make something for the public not like anything they will find elsewhere in the world.

Boss Pinkley agreed that this kind of destruction was impossible for Wetherill to prevent, so he contacted headquarters, and they devised a plan to address the problem. They came up with funds to hire John’s nephew, Milton Wetherill, as a junior ranger at half the regular wages. Milton established a camp below Betatakin where he stayed full-time during the tourist months. He went well beyond the call of duty, studying the archaeological literature so he could better answer visitors’ questions, educating himself on geology, recording animal sightings, and collecting and cataloging the plant species within the monument. Pinkley was well pleased with his performance. “…I might say that if everybody in Southwestern Monuments service did as much ‘thinking per dollar paid them’ as Milton is doing, there would be no question about whether or not we were handling our jobs successfully.”

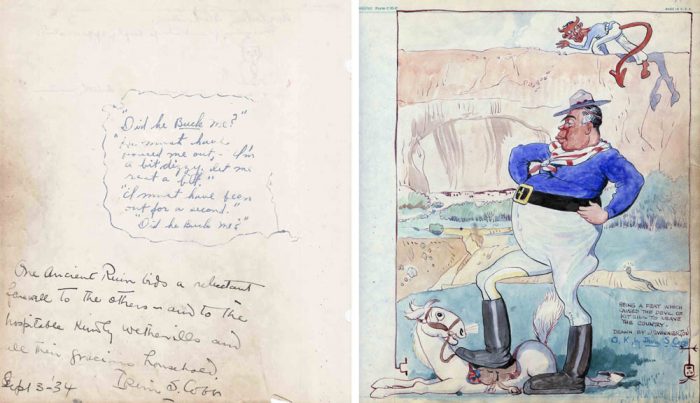

In September, 1934, Hosteen John took the artist, Jimmy Swinnerton, and the author, Irvin Cobb, on a three-day trip to the monument. In a rare mishap, Cobb’s horse got tired of the writer’s 240 pound weight and bucked him off as they were leaving Keet Seel. With Cobb’s permission, Swinnerton memorialized the event in the Wetherill’s Kayenta guest book.

“It was with great surprise and disappointment that I read your letter of August 22 in regard to taking Milton off the work at Be-ta-ta-kin,” Hosteen John wrote Boss Pinkley on August 27, 1936. John pleaded with Pinkley to do something to ensure the continued protection of the “most wonderful Cliff Dwellings in the world,” and even offered to pay Milton’s wages, himself. Lacking a satisfactory response, John wrote Arizona senator Carl Hayden and the director of the National Park Service explaining his case. He apologized to Boss Pinkley for going over his head. His letters had the desired effect, because funds were found to keep Milton on the job. However, in 1938, the Park Service advised Milton that he would have to pass the civil service exam to retain his job. He failed it and was replaced with another ranger, F. V. Leicht.

In May, 1938, the authorities informed John Wetherill that he would have to submit the results of a medical examination to retain his custodian position. John was seventy-two years old, of declining health, and had been on the job for twenty-nine years. On May 29, 1938 he wrote the Park Service, saying, “Turn my position over to some one who can draw a salary.” That fall, the authorities replaced Leicht with a permanent, full-time ranger, James W. Brewer, and Wetherill’s position was formally terminated on December 31.

Thus ended an almost thirty-year saga that was probably unprecedented in Park Service history of a dedicated volunteer who expended untold effort and time to a cause that he was passionate about—protection of the architecture and handiwork of the monument’s archaeological treasures and the enlightenment of its visitors. Little can modern visitors to Navajo National Monument comprehend the rich legacy that preceded their sojourns there.

.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Fascinating history of John Wetherill’s amazing efforts to protect and preserve ancient ruins and the National Park/Monument creation. Awesome historical photos and artifacts.

Wonderful account that Harvey Leake has given us. Harvey brings to life people and places based on his considerable research & travels. His astounding photos drew me into the story like metal filings to a magnet. Through the years I’ve visited most of the sites Harvey mentions. Thanks to his vivid descriptions they take on a new dimension in my memory. Hope you enjoy this great read.

Best history lessons are found in the CCZ.

– Ron Wilson

This is a very interesting history of the national monument status of an important ancestral puebloan site but also a history of how little the dominant non-native society knew about this place at the time. Three years before these ruins were made a national monument the Hopi Village of Orayvi, misspelled Oraibi in the literature, had an intra-village civil war and the losers were forced to leave. Those who left were headed back to where they came from, a place called Kawestima in the Hopi language. Kawestima was the Hopi place name for Keet Seel, Betaakin, and what is now called Navajo National Monument. When the group that left Orayvi stopped and camped at Hotvela Spring on the way, the army took many of the men away, winter set in, and this temporary camp turned into the Third Mesa Village of Hotvela. (spelled Hotevilla on maps.) Today there are still Hopis from Third Mesa villages who travel to these Hopi ancestral sites in the new to them Navajo National Monument to visit the shrines and springs of their ancestors.

Having hiked to all but Rainbow Bridge, Wetherill’s history deserves our sincerest thanks for really dedicating his life to saving those wonderful sites for posterity, Without his caring, certainly not monetarily rewarded, those of us in later years would not have had the great pleasure of viewing those historical monuments.

Thank you, Harvey, for the humility, dignity, and dry humor you bring to the story of the Wetherill contributions to protecting these special places. You really made me laugh with your comment about the frequency of articles requested by the Zephyr.

A great manifest of the power of one man to spread his passion into the hearts of others. Goodness is the.most contagious of qualities! I think, however, I received the greatest satisfaction in reading and enjoying the ads on the bottom of this page. They are like a time capsule of ads one used to find from the back pages of magazines, or local tour guides. All the best to this website and your work!