When I lived in South Dakota, one of my favorite places was a truck stop on the western edge of Rapid City. There wasn’t anything particularly special about this truck stop—except…maybe, for the quality of the pie in its diner. The diner was open 24 hours a day, and I wasted time in its booths on different days, at different hours. Sometimes in the middle of the night. A few times, in the early morning. Often midday, between appointments.

It was a truck stop diner exactly as you might picture one. Two dining rooms, each with dim lighting and a continual fog of cigarette smoke. A smaller room at the entrance, with a long formica counter stretching its full length. The kitchen was behind this room. And a larger room lined with Naugahyde booths and enormous double-sized windows that looked out on the parking lot and the wide pumping area.

In the smaller room at the long counter were small stools that held men—it was usually men—in ball caps and heavy coats, who would swivel in place to glance at anyone who walked in. Not with expectation. Only curiosity, or perhaps boredom. This was a truck stop, after all, and not a downtown diner, where a new face is an affront to the natural order of things. The last thing you expect at a truck stop is to see someone you know. And so the men would pivot back to their meals as you walked by, into the larger room with the booths and the large windows.

I liked this truck stop diner for precisely that reason—everyone in it was a stranger. And, though I lived in the area, I preferred the opportunity to be a stranger too. I was usually killing time between one thing and another. I might have a book with me, and I would have told myself I was going to eat a piece of pie and read while I lost an hour. But, inevitably, I left the book unopened on the table. I spent my time watching the ever-changing scene outside the windows. Little cars idling in the parking lot. Trucks that lumbered in off the interstate. Each had started the day in another place. A truck stop, after all, is where Bozeman meets St Cloud; it’s where Denver meets Fargo.

I liked the little dramas. A woman changing her baby’s diaper in the backseat of her car. A man kneeling in a crouch, looking beneath his tractor to inspect the kingpin. Another man rushing down from his cab and jogging toward the rear door of his freight trailer. A tired, quiet couple standing by each other at one of the diesel pumps; the wife, paging through their trucking manifest. The husband staring without enthusiasm over the greasy mud puddles toward the lights of the diner.

I liked the way the pavement was pockmarked with pits and stained in interlacing patterns by decades of hot black rubber treads. The milky reflection of winter sunlight in the wet potholes. The thick clouds of diesel smoke on a cold day.

I would sit at my booth with my pie, and imagine the scene like it was straight out of a detective novel. That’s what detectives are, after all. Strangers. Impassive observers, unaffected by the events they investigate. Think of Sam Spade, and the coolness with which he dispatches Ms O’Shaughnessy to her fate in The Maltese Falcon. That’s what it means to be a stranger. To stand apart from whatever scene you’re observing. To place each particle of the scene into a relationship with each other, except for yourself.

It’s the dream we don’t generally discuss. The dream of being a stranger. When we were children and we imagined hopping onto freight cars and hobo-ing across the country, we were making ourselves into strangers in our minds. All adventurers are strangers. Castaways and orphans. Sometimes, as adults, we might imagine—just for a moment—abandoning our children. We wouldn’t do it, but there’s a small release of tension when we imagine driving away from everything, leaving the responsibilities of the home we’ve made in our rearview mirror. We might think of walking away from our desks at work, and never returning. Changing our phone number. Changing our name. If you’ve ever changed your name—as many women have—you might have discovered a little frisson of excitement as you sloughed off that old life. There is possibility in becoming a stranger. Anything might happen.

Of course, on the small scale, being a stranger is not such an uncommon sensation. It usually arrives with awkwardness. The old become strangers in a room of young people. A child is a stranger in a room of adults. If you walk into a room and feel that a conversation has swiftly been drawn to a close. If you walk out of a room and feel that a conversation has just been re-formed after your departure. You were the stranger.

In a foreign country, with foreign words and foreign signs, the words on a menu can exclude you. The context of jokes. The architecture of neighborhood blocks and the peculiar tubes of foreign condiments. All of the minutiae of millions of people’s day-to-day lives, existing happily in concert with each other, do not relate at all to you.

In one particularly foreign moment a few years ago, my husband Jim and I stood on a sidewalk in Dublin, staring at the electronic sign announcing the next bus arrivals. The words on the sign—were they even words?–were entirely incomprehensible to us, and I was beginning to get nervous. The times made sense. 13h20 meant 1:20pm. 14h10 meant ten minutes past two. That much was logical. But what was the stream of gibberish where the bus destinations ought to be? How would we possibly get to the train station? We were perplexed, with no idea where we might appeal for help.

An older gentleman stopped nearby on the sidewalk. He looked at us, smiling while we fretted. He was wearing a dark woolen coat and slacks, and a blue hat against his white hair. He had an unmistakable air of knowledge. As he caught our attention, he gestured toward himself. We walked nearer to him, and he pointed back at the sign. Now, from the alternate angle, we could see the text in English. The other side had, of course, been in Gaelic. We laughed, feeling like complete idiots. He just continued to smile.

“Remember,” he said, with a lilt, “there are two sides to everything.” And he tipped his hat and continued along the sidewalk.

Being a stranger can be painfully uncomfortable, or it can be a pleasure. If you can maintain a childlike curiosity, and a willingness to not stand at the center of the scene, it can be a delight to sit back and listen to the babble of untranslated conversation. To watch children clutching their peculiar satchels as they race to their schoolyards in the morning, or to see women chatting in their front gardens in not-quite-fashions that seem oddly antiquated, or just inexplicable in pattern or fabric to the fashions back home.

But behind all this pleasant foreignness, there is still one word: home. The place where your sentiments lie. Where you aren’t a stranger to anyone, and you share a language and familiar history and common way of life. Every adventurer’s saga and every orphan’s boxcar journey ends with the comfort of finally belonging someplace. To be a happy stranger, you must have the idea—if not the reality, then at least the dream—of a home.

Why am I thinking about being a stranger? It’s a word I’ve been hearing lately. We are strangers to each other in America. One half, or another half, of the country feel like foreigners in their own home. We can’t get comfortable with each other because we don’t feel that we share a common language or a common history. We don’t even share a similar perception of the events that flow through digital print each day, and stream across banner headlines on the television sets. That other group—it’s always the other group—is excluding ‘us’ from ‘them.’ How will we ever be a family again? How will we stop being strangers from each other?

Being a stranger, in our language, generally implies unhappiness. Loneliness. And of course it’s deeply upsetting, to feel someone is saying, “This is our country, not yours. Deal with it.” As some people now feel they’re being told in the wake of the recent elections. As other people felt they were being told four years ago. If this isn’t my home, then where is my home? You might ask that, and not hear any satisfactory answer.

No one wants to become estranged from their home. Think of personal estrangements—not the dramatic kind, but the slow kind. The friend who, over time, takes on different interests and picks up on different slang. The one who takes the job in another city, or whose focus turns to people you’ve never met and events you don’t experience. It happens slowly, all your familiarity stealing away with greater pauses between conversations. Longer silences between you when you speak. You need more words to explain yourself, and those words aren’t enough to make anything plain. And one day, you recognize that you’ve become strangers to each other. That’s a terribly painful feeling.

And, alternately, one of the great pleasures of life is discovering that a once-stranger isn’t strange anymore. That, with time, somehow this other person—their peculiarities and funny tastes and their experiences—have become familiar to you, so that there’s no distance between you anymore. Your jokes make sense to each other, and you know the name and attitude of their boss, or how they feel about their family. You require fewer words to explain anything to each other. That is delightful, when you realize it has happened. It’s natural to wish for more friends, and fewer strangers.

No one would want to be surrounded by strangers.

Maybe it’s inescapable. This is a strange time—probably not the strangest time in our history, but certainly the strangest in quite a while. And it’s natural for that strangeness to become a filter over perception, casting everything we see in an eerie glow.

Even our friends look like strangers now, wearing masks over their faces. I had never realized until this year how important other people’s mouths are. To interpreting mood. To understanding a joke. And, for myself, how any constraint on my face makes communication feel impossible. I’m naturally a soft speaker. A constant refrain from my parents and teachers when I was a child was, “Speak up, Tonya!” Which triggered a more painful shyness that often left me silent. I’d almost forgotten that feeling until this year. Muffled by a mask, I’m continually told, “I can’t hear you. Can you say that again?” And I feel that same shyness kick in. My immediate thought is, “Oh, it isn’t worth it.” I end up saying very little at all.

Those of us who enjoy quiet and solitude have found that this year is both a blessing and a curse. With the push to stay home came a certain relief. An excuse, finally, not to see anyone. Not to go out and meet anyone. When your home has everything you need—the husband you love and your pets and plenty of books and food to keep you occupied—what was ever the point in going out? It’s frightening out there. Outside means the specter of disease and death, and also the pain of this year’s political fighting, which comes up too often in simple chats on the street. You could stay inside, and just avoid all of that. No one can fault you for it. Not this year.

You might forget that, all those times when you did force yourself out the door, and push yourself into rooms of people, you generally enjoyed yourself. You encountered new friends, and heard strange stories and interesting ideas, and felt generally a part of something. You might forget that you occasionally needed that—happy loner that you may be—to feel like you existed as a piece of a larger world. Even you. You need the unpredictable jumble of other people.

But the larger world–where is it now? Even if you wanted to join it, you couldn’t.

I’ll grant that I’ve never been one to participate much in the world. I prefer to sit someplace, ideally with a cup of coffee or tea and, oh, perhaps a piece of pie, and watch the world move around me. I like to observe things at a remove, without being a part of them. The consummate stranger, I like the world when it’s bustling and lively, and just a few feet away.

As I write that, I’m reminded of a night I spent in New York City a long time ago. The moment I’m recalling took place on some anonymous block in Soho at four in the morning. I didn’t have a key for the apartment where I was supposed to stay for the night. The owner was in one of the outer boroughs for an event that, I now understood, wouldn’t end before dawn. And so I had time. A few hours to walk and exist in the city with nowhere to be. It already sounds a little romantic, but I wasn’t feeling romantic about it. I was exhausted and I was annoyed at this unexpected orphaning. I was just walking along, trudging through the streets, feeling particularly ill-done-by and grumbling to myself. But then, by some chance, I paused.

I stopped at the corner of one block, and glanced up from the pavement. And finally, I recognized that I hadn’t been paying attention. I felt the rarity and the sweetness, suddenly, of what was around me.

It was a mid-July night, softly warm after the sticky heat of the day. At four in the morning, there were people everywhere. Light spilled out from open restaurants and bars, mingling with the yellow circles of streetlights to illuminate the sidewalk like a stage. A group of people poured into the street through one open door, yelling and laughing. An insomniac dog-walker stood impatiently next to one tree. Down the block, a couple leaned against each other by a lamppost. And some drunk girls were standing at a storefront near me, taking exaggerated and loud interest in some late-night window shopping.

There were a million little scenes playing out. I hadn’t even noticed them. Now, standing slightly apart from it all, in the shadow cast by the corner of one apartment building, I watched. Just for a minute or two, before I continued my walk. But as I made my way down the street, I wasn’t complaining anymore. I was smiling.

I’ve smiled at that memory a number of times since that night. I like to imagine that particular street, from my quiet home in Kansas. A street where people are still laughing and rushing around at four in the morning. I like to know that it exists, even without my being there to watch it.

I should put that into past tense. I liked to know that it existed. This year it came to me with a pang that my Soho street wasn’t itself anymore. Thousands of miles away from me, it had changed itself overnight. The restaurants and bars were closed. Their lights were turned off. All the people were cloistered in their apartments. Others were in hospital beds. It’s possible my one dog-walker, whose needs were truly essential, stood at the tree. But my ever-bustling mental street had been emptied. And with it the larger world. The world in which people jostled against each other and brushed past each other—the whole furious bazaar of human society—had fallen into a somber hush.

And all the strangers, behind their closed doors. They became increasingly strange in their silence. Living indoors, and thus online, they are something different from the strangers they were to me before.

There is an unbridgeable difference between an avatar on the internet—some theoretical person who is as fake to you as the banner ad across the website you’re visiting—and a real stranger. Real strangers have salt stains on the cuffs of their trousers. A real stranger has the particular expression of his thoughts on his face, a particular quirk to the angle of his mouth. A real stranger smells like the Indian restaurant where she ate lunch. Or is speaking with a un-placeable accent.

No one smells like anything online, for better or worse. No one walks funny online. No one actually laughs out loud or frowns, or shows any true range of facial expression. Frozen in their staged photographs, they may or may not be real persons. That family may or may not be their actual family; that dog, their real dog. This may or may not be who they are in real life. “Real” life being the life with offices and restaurants and family gatherings. The life we aren’t living right now.

It’s no wonder half the country feels like strangers from the other half. And vice versa. It’s no wonder one half feels misunderstood, and the other half persists in misunderstanding. (Whichever you want, by the way, if you’re asking yourself which is which.) If anything, it’s a statement on the terrible isolation of our time, and the deprivation of our lives, that we’ve convinced ourselves there are only two flavors of stranger. Two! There should, in a healthy world, be an endless variety of strangers. Everyone is peculiar and strange. What sort of flat, bland, flavorless existence are we living, that we have lined up for this sorting into left-flank and right-flank and called that strangeness? How incredibly bored we must be. How incredibly boring we’re becoming.

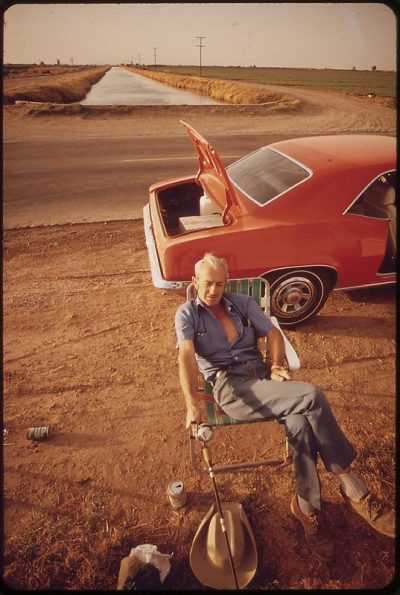

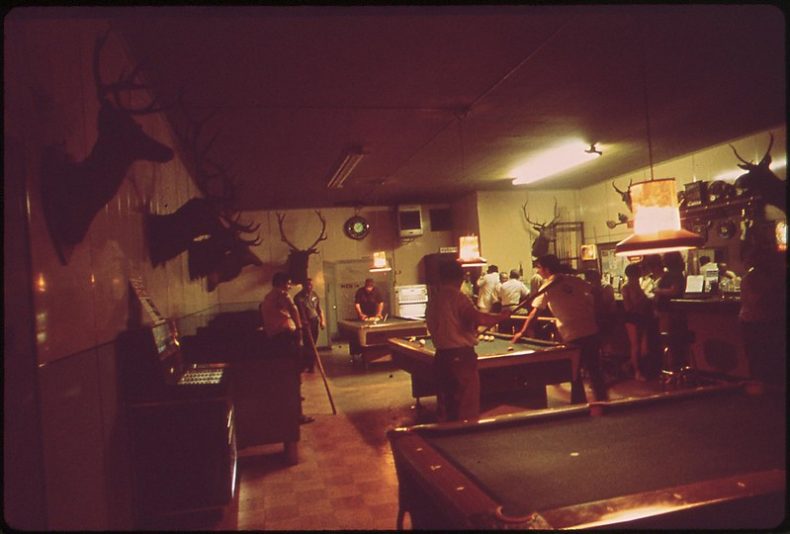

In the times before technology “united” us (great job there, technology) this country contained multitudes. Fishermen in trawlers off the gulf coast of Louisiana lived in an entirely different world than the men shuffling car parts off the assembly line in Michigan. Librarians in snowy Maine had only page-worn images in mind of the lives of shopgirls in Los Angeles. A kid in Harlem spoke a different language from a kid in dusty Nebraska. We were a nation of strangers. Did that always work well for us? Of course not. But it was fascinating. Scintillating. From the tumultuous clash of a million co-existing cultures, great minds were honed. Great ideas blossomed. That was always the dream in e pluribus unum. The weaving of one country out of a million colorful lines of thread.

Now we’re weaving, what, an unmatched pair of socks? You stay on your color and I’ll stay on mine. With only two options, every decision is zero-sum. Every territory is a tug-of-war. That philosophy has poisoned the political atmosphere, and polluted our thinking. We’re living a duopoly of the mind. Such thinking is so simplified, it explains absolutely nothing. It kills every interesting thought—save for the notion that those other guys are a problem. Everyone is so focused on getting those others back into line, they haven’t noticed that they’re standing in a line, for pete’s sake. Get out of the line. The line clearly isn’t helping. Calling endlessly for “Unity” isn’t helping. Let’s talk about tolerance instead. Let’s try to find some pleasure in the weirdness of each other.

We’re never going to understand other people. That’s just how it works. All you have to do is stand in a grocery line and watch everyone checking out around you. A woman wearing a pirate hat buying two cart-loads of junk food? God knows. An old guy with six 48-packs of Busch beer and nothing else? Well, that’s worrying. But maybe he has a good reason. I recently watched a sad-looking man empty his basket onto the conveyor belt: twenty separate one-serving pecan pies, a can of chili, and three packs of gum. I couldn’t, for the life of me, tell you what his story is. I will say that I spent more than a few moments wondering. He was a stranger, after all, in the best sense of the word. And I like strangers.

In the desire to understand each other, we tend to make things worse. “You have to kill a thing,”D H Lawrence wrote, “to know it satisfactorily.” And even if that were an option, once you’ve killed the object of your curiosity—what then? Once it’s filleted in front of you, all veins and tendons, it’s lost all the animation that made it worth observing in the first place.

No, let’s leave each other with a little mystery. We could just admit that life is a slightly different sensation for someone who lives in a different place—the middle of a city block, while we live in the country; or for someone who was raised wealthy, while we were raised poor; raised an orphan, when we were loved; raised with different tools in their hands than the tools in ours. We won’t ever understand each other. Who cares? That’s the fun. We could have common goals, could possibly coexist, without needing to alter each other. We could accept that some foreign logic might arise from foreign situations, and not despise each other for reaching differing conclusions.

Do you remember what people are like? They’re awkward and silly, but for the most part they don’t want to hurt you. It’s important to remember this, because we may not be jostling against each other as often for a while yet. We may have to wait a while longer to rejoin each other in the larger world. We won’t have the same opportunities—not for a little while longer—to watch each other stumble on the carpet edge, or spill coffee on ourselves. But that’s still who we are.

In the meantime, we can remember that there’s an incredible pleasure in the strange other-ness of people. Their peculiar faces. Their movements and foibles. There are plenty of others out there, but they aren’t villains. They’re just strangers. They happened to stop at this same gas station. They happened to come to this same grocery store, and are perching on one foot, six feet behind you, trying to get a pebble out of their shoe. They’re trying, trust me, to be friendly. From behind that mask, they are trying to show you they’re smiling with their eyes.

Tonya Audyn Stiles is Publisher and Managing Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

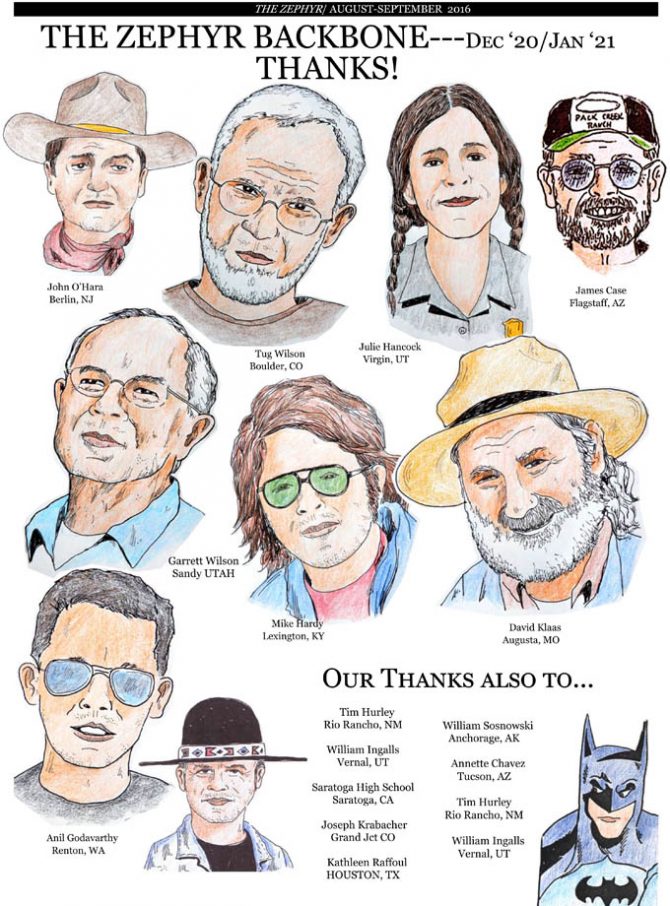

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

This is the most insightful article I’ve read in a long time. I too have spent many hours watching people, sometimes by walking down the airport concourse (when was the last time we could do that without being searched). Sometimes, as you did, from the booth of a truck stop, or exploring shopping mall at Christmas. Now, as you’ve described so brilliantly, I feel terrified of the weekly grocery shopping foray. My small Nevada town has become very contentious for many reasons, many of which you wrote about in your article. But now the town is being “invaded” by California refugees, flooding our streets with their cars, and our legislative halls with their californication. Strangers. Yet, most of the people I’ve met in this town since we moved here (from California) ten years ago, are Californians who moved here even before us. The fifth-generation ranchers sequester in their own enclaves, avoiding contact with all of “us.” And the Washoes? Shaking their heads, “who are these people? Why don’t they go away?” Your article clarified the fear, the anger, the separation that has existed way before the pandemic. Our parade of prejudices adding floats and bands each year to add more fear of each other. And I’ve become increasingly aware of the depths of my own prejudices and the fear of being judged by others too. Indeed, dear Tonya, when will we be able to accept each other for our sweet silliness and imperfections? Thank you for this article, Tonya. May you and Jim have a lovely holiday.

Tonya, more than ever I want you and Jim to stop by my home on one of your trips out west. I know Jim is supersensitive about bringing the virus to us old people. We could visit outside in the summer or 6 feet apart in our living room. I’m saying this because I resonated so well with your article. I too have felt a sense of relief that I can stay home or go photographing where there are few if any people and not feel guilty. At the same time I miss meeting friends at church or stopping to visit at the Post Office or the grocery store. With your attitude I feel that, even though I am a weird stranger, you might not be too harsh with the way I see life.

Tonya, this is gorgeous. I can only add that there was (and still is) a plague thoroughly as annihilating and insidious as COVID. That pandemic is gentrification. The vampires (forgive the mixed metaphors) set up in little Western towns; city neighborhoods made vital by diversity; previously unknown natural intersections of beauty and healthy wildlife; beaches; riversides…

Good stuff…….Wow, really good….Need to tune in more often…. Something to say, indeed…. Zephyrs, your spirits reveal that which rarely get to fly, and rarer still become still for satisfying contemplation……Made my day, thank you.

ah like this perspective, and the processes by which (it seems) you operate. timely (espesh in theez times!) yet timeless.