Tonya and I live in what is nowadays one of the most remote parts of the country. The High Plains are not known for their scenic splendor (though they are scenic to the discerning eye) and tourist traffic is next to nil. We’ve lived here, in a small farm and ranch community, for over a decade and we still come closest, in the eyes of many, to qualifying as tourist interlopers.

Because we live a fairly solitary life to begin with, and because our lifestyle is shared by many of our prairie pals, the COVID-19 Pandemic and subsequent shutdown has not been as keenly felt here as in the big cities. As one western governor noted, “We’ve been practicing ‘social distancing’ for 150 years.”

Still we enjoy wandering about, and exploring new destinations, and like most of you, we have been confined, more or less, to our part of the world this year.

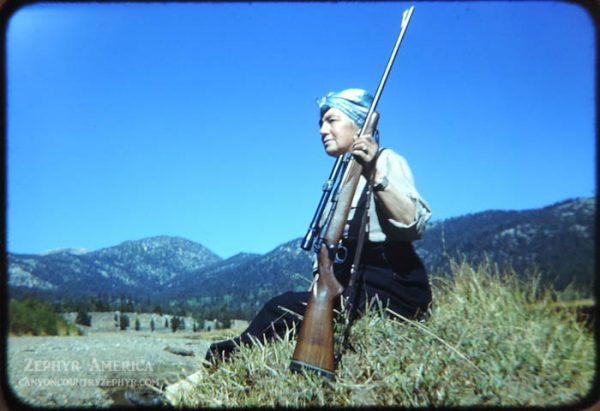

In September, we decided it was time to stretch our wings and try to live normally again (or as “normally” as possible). Last year, we took a trip out to Nevada and the Northern California coast; we had attempted to retrace the travels of our dear friend Herb Ringer, whose Kodachrome images of the American West, dating back to 1940, have been a regular Zephyr feature since Volume 1 Number 1. But we weren’t able to complete the job. There were so many amazing images by Herb, and so little time to find them, and we vowed to return as soon as we could.

And so, Tonya and I, with some trepidation, booked a flight to Reno and from there, rented a car for two weeks. What would it be like to travel around the West during this never-ending coronavirus pandemic? Would it be the frightening experience some thought we’d be confronted with? Was it a “big nothing burger” as others anticipated? We didn’t intend to be reckless, but we also felt the need to live our lives. If masks work and if social distancing is effective, our trip plan would serve us well–we mostly planned to explore the empty parts of the American West we love so much.

Here are a few tidbits and anecdotes from our recent journey. And to remove any anticipatory concerns, we arrived home safely, seventeen days later, covid-19-free and have remained so.

The Airport Risk Assessment: Covid v Metamucil

It’s a two hour drive from our home to the Eisenhower International Airport in Wichita and so we were on the road at 5 AM to make our 9 AM flight. Tonya is the most determined person on the planet not to be late for anything, and since I am the second most determined, it works well for both of us. We get through lines early and then spend hours and hours staring at various ceilings and eavesdropping on nearby conversations. It’s a hobby of ours.

Our early arrival assured us that the line through security would be light and we might have been quickly examined and on our way, had it not been for the small jar of fiber supplement that I always travel with. Not to offer too many details, but since I have not been scrutinized by a medical doctor in decades, I take self-precautionary measures to reduce my own health risks and have consequently been downing what I call “my refreshing orange drink” since I was 30. But the plainly labeled orange canister sent the TSA agents scrambling. The next thing we knew, I’d been pulled out of line and the agents were testing the contents for explosives and, I don’t know…germ warfare?

I kept saying things to the agents like, “Man, this stuff really keeps me regular,” but they either didn’t hear me or were ignoring me, and Tonya muttered in my ear, “You’re not helping things.” When it was finally determined that my Metamucil did not pose an explosive or biological risk, we were turned loose to await our flight, which was now only two hours away. Or so we thought.

Why, United? Why???

Let me offer a few words about United Airlines. I have been a “frequent flyer” with United for 25 years, which speaks volumes for the masochistic aspects of my personality. I have not booked a single flight in at least 20 of those years, where United didn’t alter or delay a flight, or change my seating, or just cancel the whole damn flight. I have spent long, miserable, sleepless nights at O’Hare when inexplicably delayed flights resulted in missed connections.

Three years ago, even Tonya, who is the Last Bastion of Calm and Reason, almost lost it with a United functionary over a last minute itinerary change. It’s as if a deadly combination of bureaucratic sadism, coupled with a unique type of bovine stupidity, is now a requirement for employment.

On this morning, we had been warned it would be a “full flight,” and United told us that if we were concerned about possibly contracting the Coronavirus as a consequence of the close quarters, we were free to make other arrangements! (I offer the exclamation mark here, ONLY as an alternative to unprintable expletives). I guess maybe they thought at this last moment, we could catch a cab to Reno.

Still, we boarded our flight only a half hour late, which we considered a near-miracle, for what promised to be a near-on time departure. But lately the airline has developed a new technique to drive us crazy. The ground crew guides the plane out of the gate and the pilot taxis a couple hundred yards onto the tarmac, and we all think we’ll be airborne in a matter of moments.

But then the aircraft stops. And we sit. And we sit a while longer. No explanation. Time passes. And of course all of us are COVID-19 masked and receiving half the oxygen we need to maintain our bodily requirements, and some of us start to squirm and fidget. Finally the captain comes on the intercom to explain that the landings are backed up at DIA (Denver) and that we’ll be sitting here “a few moments longer,” proving yet again that United measures “moments” in geological time.

Oh well…right? In the whole scheme of things. Doesn’t matter. We had a layover in Denver, landed intact, and discovered that the concourses were packed with fellow humans. It was a strange sight to behold—thousands of mostly law-abiding citizens, mostly wearing masks. In all our time in airports and departure lounges and on the planes themselves, we observed one unmasked fellow passenger. We now reside in a masked world.

Escaping Reno…to Gerlach & Beyond

We eventually landed in Reno, de-boarded the plane in a fairly orderly fashion, secured our rental car and were on the road in a matter of minutes. Almost immediately, at 3 PM Pacific Time, we encountered pre-rush hour bumper-to-bumper traffic on Interstate 580. Our plan was to escape the city and the human hordes as quickly as possible, but the gridlock slowed us down. Still, after a few minutes, the traffic thinned a bit, we emerged from downtown and headed east on I-80 just briefly, until we found our connecting road and escape route, back to the quiet and calm we always seek.

We went from a scene like this…

…to this, in about an hour.

Life seemed good again.

We chose Gerlach to spend the night because the town’s tourist services in its entirety included one motel and one restaurant/bar. Both under the same ownership. To check in at the motel, you went to the bar. We went from an international airport where we mingled with thousands of masked individuals to “Bruno’s Country Club: Motel-Cafe’-Casino-Saloon,” where we mingled with about ten fully un-masked miners and ranchers. I have to admit, it was good to see teeth (and smiles) again.

For much of the road trip, our experiences were very similar to Gerlach. It was quiet. Social distancing was a way of life. We wandered into a tiny remote corner of California, that never felt like California at all. It was in all ways other than GPS location, rural Nevada. We ate a spectacular breakfast at a cafe in Cedarville called the Country Hearth, and as we approached the cash register to pay the bill, we realized that this diner was also a bakery of unrivaled quality. The owner, who kept the woodstove banked as well, was known locally for her baked delights. We bought a couple of chocolate eclairs which we devoured an hour later, standing over a dry lake bed north of Surprise Station. For some reason, Tonya felt obligated to record the moment when I tried to shove more eclair into my mouth than would fit into it.

Klamath Falls was a tad hectic and the checkout woman at the local Safeway advised us to flee while we could. She apparently loathed Klamath, was sure it was the meth capital of Southeast Oregon, and said she’d be fleeing as well as soon she could get together enough money to go…and when the pandemic finally came to an end (we assume she’s still there). We left Klamath an hour before dawn, managed to get coffee to-go at an otherwise empty Denny’s from a kind young woman who was happy for some business, and we watched the sun come up over nearby Klamath Lake, a few miles west of town.

We found Arlene’s and her world famous pies in Elkton, Oregon as we made our way slowly, along the backroads, to the Pacific Coast. It was a beautiful restaurant and we had the place mostly to ourselves. Tonya could not resist the strawberry/rhubarb pie.

But while we always enjoy a quiet spot to eat, it’s pure selfishness on our part that we prefer the sparsely visited diner. In fact, many of these small businesses continue to hang on by the thinnest of threads. If they own the property and their built-in debt is minimal, these small businesses can probably weather the current pandemic restrictions a while longer. But if they’re dealing with mortgages and accumulated debt, with no means to make the payments, their options are dwindling rapidly and their prospects are bleak.

So many Americans have tried to comply and tried to do their part to bring this pandemic to an end, at great personal sacrifice. But, while I don’t know what the answer to this rolling nightmare is, I still wonder how it is that our government could tell us to stop working, stop going to church, stop sending our children to school through this crisis, stop seeing our friends and families, in effect, stop all contact with everyone, while offering no viable solution to the other crises–economic and psychological–these restrictions created.

It’s an enduring tragedy, with long-range consequences that reach far beyond the COVID-19 death toll.

Crescent City and the Harbor Cam

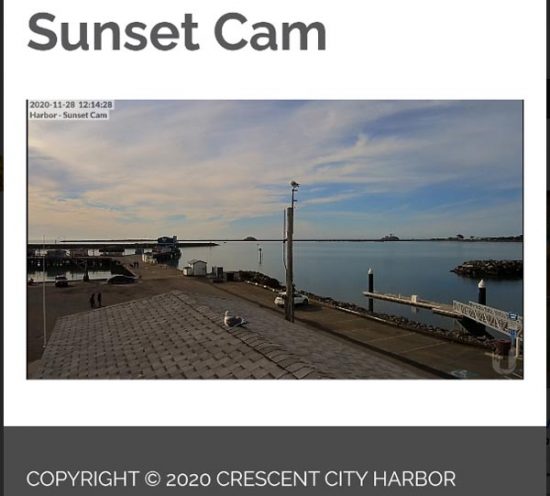

Last year, our 2019 trip to Nevada and the Northern California coast, we stayed a night in Crescent City, California. And I realized I had first passed through here in the summer of 1972, almost half a century ago. How is that possible? We both loved Crescent City–it still felt like a “real” community, with a diverse economy that isn’t beholden (yet) to a monolithic one-trick pony tourism as its primary drawing card. We loved to walk out on the harbor pier in the mornings and, when we returned home from that first trip, we discovered that there was a streaming web camera mounted on the roof of the harbor office. It’s called the “Sunset Cam” and I cannot tell you how many times we sought refuge during these scary times, just staring at that view on our screens, dreaming of Pacific sunsets and the squawk of sea lions and gulls. This is what the streaming camera looks like…

So…when we were finally able to return last month, we checked into the Curly Redwood Motel, a lodge that was built entirely from a single redwood tree more than half a century ago, and then we headed straight for the harbor. We created our own version of a Sunset Cam Selfie. In this grainy low-resolution screenshot, you can see us waving to ourselves.

Down the Coast…50 years later.

Port Orick…Westport…Pt Arena…

We stayed in Crescent City for three nights, traveled inland to see some of the lesser known groves of Redwoods, ate many bowls of crab bisque and clam chowder, and watched the sea lions do what they do best…nothing. It looked like the perfect life to us.

While one of our major objectives was to search for and find film locations for Herb’s fantastic Kodachromes, it occurred to us (as much as I resist the notion) that even some of my old Kodachrome slides have achieved “historic” status as well.

We re-located a scene on the coast, just south of Port Orick, California that I had first photographed in 1972. At the time, a lumber mill was operating and the smoke from the sawdust burner is visible in that original photo. Today, there isn’t a trace of the mill and the land has been rehabilitated and incorporated into the California parks system. A visitor center now sits where the mill once operated. On this trip, of course, the visitor center was closed, due to COVID-19 and had been like that for months. The town once supported four sawmills and a population of over 3000, but now it’s practically a ghost town.

In fact, it was only the offshore features–particularly the two spires that are visible just a few hundred yards off the coast that told us we’d found the right spot. Here is what it looked like in 1979…

..and now.

We left US 101 at Leggett and followed the narrow, winding Pacific Coast Highway (California 1) for 30 miles, and finally emerged from that very deep forest and the highways and its hairpin turns to see the Pacific again. Just south of the spot where PCH1 meets the coast, we stopped in the tiny community of Westport for a sandwich. I remembered the general store that I’d paused at in 1972 and was relieved to see it still operating. Here is what it looked like 48 years ago…

And with just a few modifications, today…

And finally, to a spot I first saw in a driving rain, almost half a century ago. In those days the Point Arena lighthouse was still operational and was owned by, I think, the U.S. Coast Guard. I remember I couldn’t get within half a mile of the structure and I spent the night sleeping in my VW Squareback, along the side of what was then an otherwise deserted road.

Now it’s a tourist attraction with a fee station and guided tours. On this particular day, the parking lot was full. The Pandemic probably had slowed down the traffic some–this was a Sunday afternoon.

We saw many people, here and down the coast, wearing masks. Some wore their masks inside their cars; others even wore them outside when they were hundreds of yards away from the nearest humans. I thought such extreme gestures were ridiculous.

But in many indoor venues, where customers and staff were in close quarters with each other, and most people had masked up, we also occasionally saw people, staff and visitors alike, who simply refused to put it on. And that seemed ridiculous too.

I admit to having mixed feelings. But more than anything, we tried to avoid a fight. If a business required a mask, we put it on. It really wasn’t a point of contention for either of us. If we entered a place, like Gerlach, where masks were not as popular, we kept them handy just the same, and if we saw someone approaching us who was masked, we immediately put ours on, at a distance, to make her feel safer.

We saw many, many masks.

The Fires & their Aftermath.

As if the Coronavirus Pandemic hasn’t been enough punishment, those living in much of the rural West have had to endure a months-long threat from wildfires. They started last summer and even in early October, as we prepared for our trip, many of them raged on, in places we hoped to visit. Two weeks later, at least along our planned route, the fires were out, though in places we could still smell the smoke of smoldering ashes, and more than anything, we could see the destruction the fires had caused.

While the COVID-19 crisis has always been a sort of insidious threat–one that can’t be seen or heard until it’s upon us, and which picks and chooses who it intends to sicken or kill–there’s nothing subtle or surreptitious about a fire. And we saw evidence of it as we crossed the many mountain ranges that stand between the Nevada deserts and the Pacific Coast. Succumbing to extremely dry conditions and driven by high winds, fires had devastated the countryside as we passed through one burned out landscape after another.

Wildfires can also be erratic in the way they dispense damage. We found areas where flying embers had ignited one part of a forested ridge and spared the other side of it, just yards away intact and unburned. Farms on one side of the road were left charred and twisted, but across the road—unscathed.

Much of what was saved could be attributed to the tireless efforts of thousands of firefighters who worked to near total exhaustion, often to save the homes and small businesses of people the firefighters would never meet or know. In so many of these towns, and even on the lawns and by the roadsides of homes and farms, we saw the many signs of gratitude for their heroic efforts…

Extraordinary numbers of line crews from Pacific Power were everywhere, racing to replace power poles and lines and restore power. Often it was first necessary to remove the charred deadfall before they could proceed. Crews were working 24/7 to help return life to “normal,” as if that could ever happen in the near future.

As we drove deeper toward the Napa Valley, the fire damage became more intense. Hillsides once covered with manzanita and chaparral were charred beyond recognition. The vegetation here has deep roots and if the area receives some decent moisture, they can regenerate. But if these black, barren mountains receive too much rain, it will trigger land and mudslides that are sure to bring even more misery on the land and its inhabitants–wild, domestic, and human alike.

Back to “Birds Landing” & Glen and Shirleys

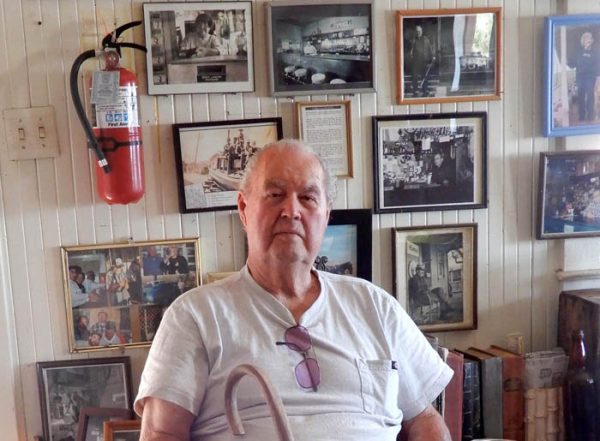

In 2019, Tonya and I visited a very off-the-beaten path village called Birds Landing, California; in fact, it’s less than 50 miles as the bird flies from the Bay Area. But in all other ways, Birds Landing is like a different world. It’s quintessential Rural America. The heart and soul of Birds Landing is Shirley’s Tavern, and Shirley Paolini at 91 was still very much in charge and holding court when we wandered into her “place” last year. We could tell it was a tavern for “the locals” and the drink of the house was tomato beer. The tavern floor was known for its peanut shell patina.

During our 2019 visit, Tonya and I got to chat for a few minutes with Shirley, but we also had a great conversation with her son, Glen Winter. It was one of those moments where we knew, if we lived closer than 2000 miles to Birds Landing, Glen would be one of our best friends–the kind of connection we all hope to find in our lives.

Tonya and I kept in touch with Glen, via the US Postal Service (good ol’ hand written letters) through most of this year, but had not heard from him since late summer. We were both worried about their health; we knew Glen had some recurring health issues and Shirley, at 91, is in as high a risk group as one can imagine. So we detoured from our route and returned to Birds Landing, hoping against hope that we’d see them again.

When we arrived at the tavern, the place was shut down and not a soul around. I walked up the steps to the front door and peered in a window, but couldn’t see a sign of life. Discouraged I walked back to the car and we started to leave, when we spotted a small golf cart coming slowly up the road. Behind the mask, we realized…it was Glen. He had no idea it was us either, but we were all grateful for the short but comforting reunion. Glen was in good health and reasonably high spirits (about as high as anyone’s these days). And he told us Shirley was doing well too.

Of course, we couldn’t even give the guy a hug, but we promised we’d be back when this nightmare finally falls behind us.

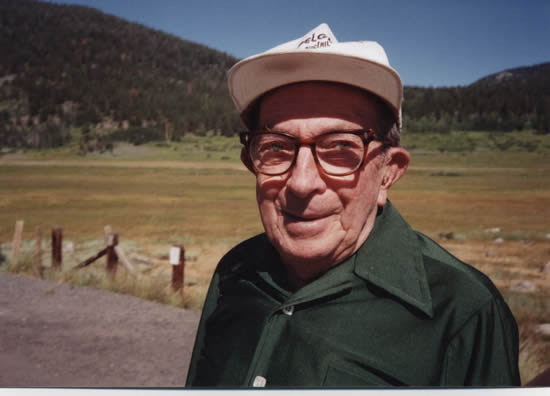

Return to Hope Valley..and Herb Ringer

If you follow The Zephyr and our long-standing love for Herb Ringer and his photography, you’ll know that one of Herb’s favorite spots in all of the American West was a little Eden called Hope Valley, high in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and about an hour’s drive from Carson City, Nevada. Herb once told me that he and his parents had made 260 trips to Hope Valley between 1944 and his father’s death in 1963. A year before he died, I took Herb up to Hope Valley one last time, to say goodbye.

Last year, Tonya and I returned, hoping to re-shoot some of the locations from his old photos. But we were only partially successful, so we planned a visit this October as well. This time we were coming on a Sunday and the weather was clear and cold. It had felt fairly quiet here in 2019 and we anticipated more of the same. We were wrong. In this COVID lull in October, the cooped up masses were out in force. Herb Ringer’s quiet Hope Valley was brimming with tourists and long lines of cars and trucks and motorhomes and trailers. In short, it was a bloody madhouse.

We were able to find a few more of Herb’s photo locations but we were also overwhelmed by the sheer business of the place. For all these years, I have seen Hope Valley through the eyes and ears and photos and written words of Herb and his dad, Joseph. Here are a few images of “Hope Valley 2020.”

Heading for the Mojave… & Kelso

We followed US 395 south, through Bishop to Lone Pine and then the long descent into Death Valley. I’ll just mention it here because we plan a much longer feature about the Valley and Herb Ringer’s 1940/50s Kodachrome images of what was one of his favorite campsites in a future issue.

Just briefly, though…At Furnace Creek we noticed that almost all of the date palm groves have been torn down and replaced with these waferboard monstrosities. They looked like they’d been half-built, then the project shut down, and now were just falling apart from neglect and the intense desert summer heat.

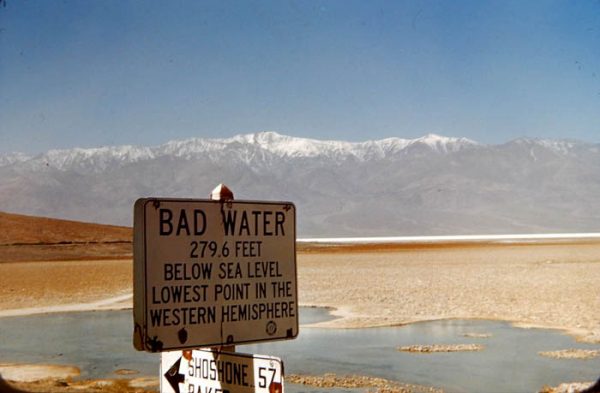

Thirty miles south, we wanted to stop at Badwater, the lowest place in the Northern Hemisphere. I hadn’t been there in decades. During my last visit, Badwater offered a small parking lot and a lot of emptiness. But the National park Service is visionary. Even before Instagram began to destroy hidden splendors like this, the NPS, in its bureaucratic wisdom, and with apparently unlimited funds, constructed this absurd concrete and steel structure…you know what they say: “If we build it, THEY will come.”

THEY came…on a Thursday afternoon in late November, Badwater was like a tourist sponge. We had not seen so many selfies being shot by so many at the same time since we left home. We ourselves departed and headed south.

I have always carried with me the memory of a particularly dark and scary night, back in the winter of 1977. After my season ended at Arches in late October 1977, my semi-girlfriend and I and Muckluk headed south and west to the Mojave Desert, in search of warmer weather. We’d spent the previous evening sleeping in the parking lot of Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas( we were broke). It wasn’t ideal but the seats folded down in my Rabbit so it was tolerable. But I’ll never forget awakening at 2 Am by the screeching Brooklyn-ish voice of a woman who was peering directly through my windshield. Her face was less than two feet from my own. She screamed, “Harvey!!! (pronounced ‘Hahhhvey!’) My GOD!!!..there’s a man and woman sleeping in that car!!! (pronounced ‘cah!’). Can you believe that? My God Harvey!” She lingered for a few seconds, dumbfounded. I think I meekly waved and said, “How are you?”)

The next morning we drove to Death Valley, via Beatty, then came south through Badwater, to Alamosa and then all the way to Baker, California on I-15. It was fairly quiet but we decided to push south on what was then a dirt and gravel road that connected with Route 66 near Amboy.

On the map, the road looked empty. But as we descended a long alluvial fan in pitch darkness, we spotted a couple lights in the distance. What could they be? It made no sense. We saw the lights draw ever closer over the next 25 minutes. Finally we could discern a building. It was a magnificent adobe hacienda-style structure, with a red tile roof and brick sidewalks. There were massive palm trees growing around it. We thought we’d found the “Hotel California.”

Railroad tracks passed in front of the well-lit building and I paused at the crossing to take one blurry handheld photo with my Yashica 35mm. It was dead quiet. We could hear one screen door banging in the distance. My girlfriend suddenly freaked out and screamed,”We need to get out of here!” And so we fled the premises. But I knew I’d return.

The next winter I came back in full daylight. The place was still impressive, but now I discovered that it had been a depot for the Union Pacific Railroad, going back to 1905. Its population boomed and shrank over the decades, with mining discoveries and the war. Now, in 1977, it was a very quiet place. I returned again in 1979 and with another friend in 1984. Kelso stayed the same.

Apparently the depot was shut down in 1986 and started to fall apart. The Union Pacific was on the verge of tearing it down when preservationists persuaded the National Park Service to save it. The Mojave National Preserve surrounds Kelso and the NPS has taken steps to preserve the building. But in the process they destroyed much of its original esprit as well. They tore up all the brick sidewalks that ran adjacent to the depot and built a tall iron fence to separate the building from the tracks. I’m guessing liability issues were at play. The NPS also cut down most of the massive deciduous trees that had been growing there for almost a century, but they did spare the palms.

This year, we followed the same road from Baker to Kelso in 2020. Baker is a busy place these days and this is what I-15 looked like as we gazed east toward Vegas—one massive block of traffic.

We kept going south to Kelso.

We found the depot intact, albeit with the changes I just mentioned. The interior was of course closed for COVID and we could not find a sign of a ranger. We were free to walk around and peek in the windows, but very few others took the time. I also noticed that in the interim, the Park Service had added another structure and clearly it’s the building that in 2020 is of the greatest interest to the traveler.

Since these desert roads have been paved, the route has become a shortcut for those traveling from the Los Angeles area to Vegas. Consequently the road gets a lot of traffic. But few of them come to visit the old depot. Few even seem to notice it.

But the recently built “other structure” has really become popular. It’s a full-fledged multi-stall, running water “comfort station.” In the span of an hour, the occupants of perhaps 30 or 40 vehicles paused here to relieve themselves. It was the ONLY reason they even slowed down. I would never have guessed, on that dark moonless night in 1977, that someday this lonely location would become a busy pitstop for needy urinators.

The world is changing.

Ghosts of flyboys at Tonopah

A couple days later, we arrived in Tonopah. We revisited the ghostly remains of two derelict army air corps hangers from WWII. I had seen them in 2019 but wanted a second look. They were of particular interest to me when I learned that the area had been a training ground for Consolidated B-24 Liberators in 1942 and ’43. My dad was a navigator on a B-24 and flew 25 missions in the Pacific Theater in 1945. I wondered if he had been here.

Now, all these decades later, the old hangers still stand. While the roofing has long ago blown off in the desert wind, and walls baked by the relentless Nevada sun, the hangers still look structurally sound. If we could only record the memories of this place.

In one back room, we discovered a pile of empty pharmaceutical bottles, stolen perhaps from a Tonopah drug store. The room was littered with ragged clothes and dirty cook pots, a syringe here and there. On a wall of the hanger, someone had spray-painted an Anti-Semitic profanity.

The world is changing.

Back to Reno…the NEW Reno.

On our last day, we made our way north through Hawthorne and the world’s largest munitions depot and the worst McDonald’s on the face of the earth (the price I pay for occasionally craving a ‘quarter-pounder,’) to connect with I-80 a few miles east of Reno.

And here we discovered Reno’s next incarnation. The “Biggest Little City in the World” was once a place to get a quick divorce (Herb Ringer drove all the way to Reno from New Jersey in 1939 for that very reason). It was once a gambling mecca, once a rival to Vegas, but now the casinos are closing and the ones still standing have a forlorn abandoned, weary look to them. Now ‘New Reno’ is here…in spades one might say. A few miles east of the city itself…

I could try to describe in words what we saw as we descended the new highway to the Interstate, but to be more succinct, here is how Wikipedia explains the phenomenon…

“The Tahoe Reno Industrial Center is a privately owned 107,000 acres (167 sq mi) industrial park, located east of Reno, Nevada and south of Interstate 80. The center is the largest in the United States, occupying over half of the land mass in Storey County, and is home to more than a hundred companies and their warehouse logistics centers and fulfillment centers such as PetSmart, Home Depot, Walmart. and others. The Gigafactory is being built there to serve Tesla Motors and Panasonic. Tesla says that once completed the Gigafactory will be the largest building on the planet.”

Here is how it looked…The world is changing…

The Flight Home

Finally, after more than two weeks and 4000 miles on the road, we were ready for home. Again, our greatest COVID fears for the journey were concentrated in these flights and the terminals where we had to change planes. It was extraordinary to see so many masked individuals.

In fact, during all our time on the planes and at airports, I saw one unmasked person. I even took a picture of her, while pretending to shoot a selfie (but out of fear, I won’t publish it.) She was on the phone boasting to a friend in Billings that she’d been “busted again!” She exclaimed for all of us in the departure lounge to hear, “You KNOW I’m innocent! Because YOU have always been one of the good guys. I just know you will back me up…I just wish the feds weren’t after me too.” Then she asked her BFF, “So when did you get out?”

The writer in me thought, ‘Wow…this could be a really interesting story,’ but then it occurred to me she wasn’t worth dying for.

With great relief, we boarded our flight home. To show just how weirdly our priorities have been twisted and upended by this stupid pandemic, just after takeoff, I turned to ask Tonya something and saw a big hairy hand, almost in my face. The man seated directly behind Tonya was gripping the side of her chair-back with his left hand, and was hacking and coughing and sniffling and sneezing as if he’d been saving up phlegm for months and had decided at this moment to release his wet, snot-filled nasal cavities into the backs of our heads. I looked at him once and he looked at me and didn’t move. Then he started hacking again, and I turned directly toward him and raised my hands in an unmistakable “WTF???!!” gesture. He glared back for a moment, then reluctantly leaned back in his seat and kept his sniffles to himself.

But here’s the bizarrely bright side to “Today’s Most Revolting Moment.” As Tonya (always the optimist) noted, “Well…at least it’s a wet cough not a dry hacking cough. Spewing phlegm is gross, but at least it’s not the coronavirus.” It was the only time in my life I’ve felt grateful in some weird way to be sprayed on by a wet hacker.

We crossed over the vast expanse of the Great Basin and an hour later, I realized we were passing just south of my old home town. There she was…Moab, Utah. It looked so much more peaceful from 37,000 feet.

Later as I gazed out the port side window, I saw the near full moon rising over our beloved prairie.

An hour later we were on the ground, and after a peaceful two hour drive…home. We had missed our “Boys,” more than I would care to admit and we think they missed us, but, you know…they’re cats. More likely, they were delighted to know that we missed them.

Once home, we kept a very low profile for a couple weeks, avoiding any close contact with our friends, just in case we’d picked up the dreaded Covid Crud. But neither of us ever got the bug and a month later, as numbers tick up around the country, we are as healthy as ever and with the fond memories of our journey across the Covid American West. We watched the sun rise at Klamath Lake and returned to the Pacific Ocean and rekindled our love for the giant Redwoods. Despite the pandemic we still met dozens of Americans across Nevada, Oregon and California. We shared our feelings about the state of our country with convenience store clerks in Gerlach and food servers in Cedarville and fishermen at Crescent City. A lone ranger’s nod at Orick. Our brief reunion with Glen Winter at Birds Landing. Even the masks didn’t stop a good conversation, but I’ll be glad when this ends.

Because I miss the faces. The complete faces, that is, in all their varied glory… Truth be told, the eyes alone can only tell us so much about what people are thinking or trying to express. I want to see the smiles and the laughs again, but I also miss the grimaces… the gritted teeth. The explosive expletive-laced screams. Even blank stares, from the nose up only, leave something missing.

Sir Walter Raleigh once proclaimed, “I wish I loved the human race. I wish I loved its silly face.” For me the jury is still out on both counts, but I have to admit, I’ve missed those silly faces.

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

thanks (again) for taking us (well, me, in this case) along on your trip. me ‘n Betty have been pause-eye-tively yearning to do such a trip — even tho’ our “boys” (catzendawgz) might miss us. or know we’re missin’ them.

neat, your (more-than-just-frequently) efforts and successes @ capturing historical photo perspectives.

a few comments, ‘n kwestyunz: wichita airport? ah thought yew livid in Monticello?

in 1982 or so i was conducting geophysical research out west. i had a state-of-the-art spectral-gamma geophysical-downhole-logging-truck — which could manage maybe 55 mph on the hwy (which was a bit faster than the maximum speed of downhole geologic in(tro)spection of maybe 5 feet per minute). i had a brief job in Reno, and next stop was Grand Junction (CO). i figured, why not US50 all the way to G.J.? — as the interstate would be interminably boring, and US50 looked much more interesting. it was. a couple hundred miles out from Reno I thought the UFO’s were buzzing my truck. good thing i didn’t have a camera. later (many months) i saw photos of the proto-type stealth bombers and then realized i’d seen earlier versions out test-flying in the middull-of-Nevada-desert where they figured no-one would notice nor care.

in early 1978 Betty and I, having graduated from university and my first post-college job started in two months, figured we’d drive the entire U.S. West Coast highway from L.A. Californya up into Oregon. we vizzided many places you ‘n Tonya recently were at, and, yes, reading your commentary, (as Darth V might intone) the nostalgia is strong in this one. heh …

Again, thank you for this story!