The wealthiest person

Is a pauper at times

Compared to the man

With a satisfied mind

—From the song “A Satisfied Mind,” by Joe “Red” Hayes and Jack Rhodes

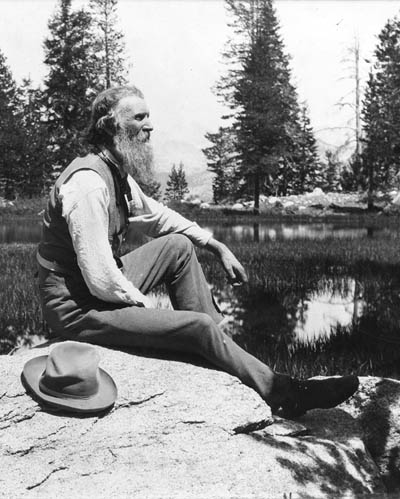

“I don’t think Mr. Harriman is very rich. He has not as much money as I have,” the noted philosopher, naturalist, and writer, John Muir, declared to his incredulous shipmates aboard the SS George W. Elder in 1899.

Muir was of humble means, and railroad magnate and financier Edward Henry Harriman, who was sponsoring and hosting the voyage, was one of the world’s wealthiest men. Harriman had invited Muir and other elite scientists, artists, photographers, and naturalists to join him on his research cruise to Alaska.

The sage explained himself: “I have all I want and Mr. Harriman has not.”

Muir’s wants were abundantly satisfied by his frequent saunters and sojourns in natural places—hills, dales, mountains, canyons, and forests that, free of monetary cost, supplied him with unbounded satisfaction. “Going to the woods is going home,” he proclaimed. “Walk away quietly in any direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Camp out among the grasses and gentians of glacial meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.”

Recognizing the need for enduring places where others could also gain these insights, Muir was a pioneer in advocating for the preservation of wilderness. “Wilderness is a necessity […] there must be places for human beings to satisfy their souls,” he wrote.

Recent scientific research corroborates Muir’s contention that the pathway to a satisfied mind leads elsewhere than the accumulation of excessive wealth. In his book The High Price of Materialism, psychologist Tim Kasser cites numerous studies that conclude that “the healthiest values […] direct us to have experiences that help us feel safe and secure, competent and worthy, connected to others, and authentic and free,” and that “those who believe [these] values are relatively important report enhanced happiness, greater psychological health, better interpersonal relationships, more contribution to the community, and more concern for ecological issues.” On the other hand, “evidence suggests that, beyond having enough money to meet our basic needs for food, shelter, and the like, attaining wealth, possessions, and status does not yield long-term increases in our happiness or well-being.”

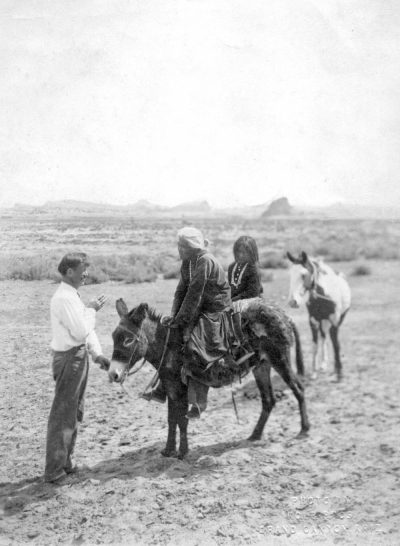

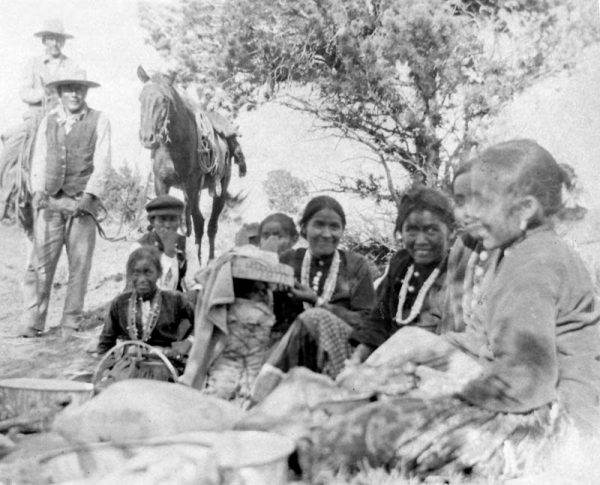

My great-grandparents, John and Louisa Wetherill, lived among the Navajo Indians in the Monument Valley area for nearly forty years, and they needed no scholarly studies to reach the same conclusion. They admired their neighbors’ authenticity, integrity, unpretentiousness, cheerfulness, and zest for life, despite their lack of material wealth.

In 1923, activist John Collier visited the Wetherills’ home in Kayenta, Arizona, to discuss with Louisa her insights regarding the Navajos. A decade later, he would be appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs by President Franklin Roosevelt, but now he was a private citizen, serving as research agent for the Indian Welfare Committee of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. He was struck by the upbeat character and sweet spirit of the Navajo people as inspired by their natural landscape. They had satisfied minds.

Collier insightfully recognized that the Navajos’ joyful demeanor was a benefit of their connection with their natural surroundings:

Perhaps it is the most ineffable note of landscape music ever heard on this planet, and all of the 20,000 miles of the Navajo country echo with this beauty which rises again to supreme power in Monument Valley and around Navajo Mountain and again at the Rainbow Bridge northward from the reservation. The Navajos hear this music, gleam with its fire and move with its rhythms. Their common speech and formal recitative are dyed and transfigured by a landscape which to them is a living and acting Soul. It, and not the casual momentary hogans built and abandoned in a season, is the Navajo house and home; and the mystical and magical dominions of the imagination which inhabit this strange landscape are an effectual part of the Navajo social life.

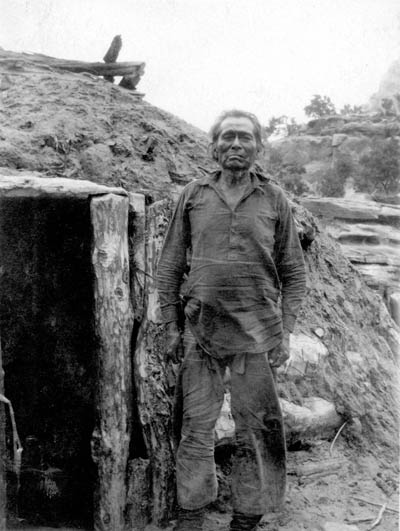

Louisa Wetherill understood these truths on a more personal level, having lived among the People for decades and, more particularly, having developed a deep friendship with an especially honorable Navajo man they called Wolfkiller. The two of them collaborated on recording his amazing story, which was published in the book Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd (For more on him, see my article “The Wisdom of Wolfkiller: A Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd and Sage” in the October/November 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr).

Wolfkiller epitomized the values that John Collier so admired. When he was six years old, his grandfather and mother began teaching him to follow the “path of light” by dealing with his irrational fears of nature and, in their place, learning to see the beauty and wisdom of his natural surroundings in all of its manifestations.

“You must live today and keep your thoughts in the path of light,” his grandfather told him. “Everything will come out all right. You must always think that the next year of your life will be more happy and peaceful than the year before, and must try to make it come true.”

Although he never had much in the way of money or material goods, Wolfkiller was bountifully rich in character, personality, wisdom, and love of life. He lived “quietly and at peace with the world,” Louisa observed.

On the other hand, evidence suggests that those who devote their lives to unnatural pursuits, such as the accumulation of wealth and possessions, can never know the rich rewards of freedom, peace, freshness, and authenticity bestowed on folks such as Wolfkiller who delight in the treasures of nature. According to Kasser, “The studies document that strong materialistic values are associated with a pervasive undermining of people’s well-being, from low life satisfaction and happiness, to depression and anxiety, to physical problems such as headaches, and to personality disorders, narcissism, and antisocial behavior.” Using the results of psychological studies, Kasser concluded that, first, “Materialistic values go hand in hand with low quality of life and psychological health,” second, “Needs for security and safety, competence and self-esteem, connectedness to others, and autonomy and authenticity are relatively unsatisfied when materialistic values are prominent in people’s value systems,” and third, “Materialistic values work against the well-being of other people, society, and the planet.”

It is not only the wealthy who suffer these ill-effects, but also those who crave fame or adulation, strive for power over others, or seek pleasure in transitory delights. Also subject to these maladies are those who admire or envy those who have accomplished these goals.

Common to these behaviors is the popular practice of distancing oneself from the natural world. “Living artificially in towns, we are sickly, and never come to know ourselves,” John Muir contended. He, too, gained insights on this subject from Native Americans: “As we sat by the camp-fire, the brightness of the sky brought on a long talk with the Indians about the stars,” he recalled, “and their eager childlike attention was refreshing to see as compared with the decent, deathlike apathy of weary civilized people, in whom natural curiosity has been quenched in toil and care and poor, shallow comfort.”

Why do so many people choose to go through life along a trajectory that inevitably leads to their dissatisfaction, and what inspires others, such as Wolfkiller, to question the so-called conventional wisdom and recognize and pursue the alternative “path of light” that leads to a satisfied mind?

In his book entitled Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing, nineteenth-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard identified a human condition he called “double-mindedness,” which seems to correlate with the behaviors that lead to unsatisfied minds. Modern psychologists call this “cognitive dissonance,” which has been defined as, “the mental discomfort that results from holding two conflicting beliefs, values, or attitudes.” The mental discomfort comes from a guilty conscience, worry, dashed hopes, vanishing pleasures, and frustration at the outcomes of fights that ultimately are impossible to win.

Numerous examples can be cited of prevalent conflicting beliefs, values, and attitudes. Here are a few of them:

- Presuming that an increase in opulence will cause lasting happiness, despite recurring disappointments. According to Kasser, “The sad truth is that when people feel the emptiness of either material success or failure, they often persist in thinking that more will be better, and thus continue to strive for what will never make them happier.”

a

- Expecting that an ever-increasing stockpile of money and possessions will solve life’s problems. “Desires to have more and more material goods drive us into an ever more frantic pace of life,” Kasser observed. “Not only must we work harder, but, once possessing the goods, we have to maintain, upgrade, replace, insure, and constantly manage them.”

.

- Believing advertisements that falsely convey that consumer products are the source of happiness.

.

- Attempting to escape from nature by taking refuge in artificial, sanitized surroundings, while avoiding the reality that we and our fellow humans are part of nature. “We have been broken off from the nature of our world, broken away from the nature of one another, broken apart from our own nature,” wrote psychiatrist and theologian Gerald May in his book, The Wisdom of Wilderness. “The pain of this breach is so constant that we have become accustomed to it; it feels normal. The pain is with us every day, when we browbeat ourselves for not handling things right, when we judge ourselves and others, when we struggle for control, when we draw circles around ourselves that shut others out, when we long for a connectedness we cannot find, when we try to help one another and it’s never enough, and, perhaps most of all, when we go outdoors and feel that Nature is something different from us.”

.

- Claiming to be a nature lover or advocate while happily reveling in increasing layers of artificiality.

.

- Denying the reality of death. According to psychologists Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski in their book The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life, “Recognition of our mortality leads us to love fancy cars, tan ourselves to an unhealthy crisp, max out our credit cards, drive like lunatics, itch for a fight with a perceived enemy, and crave fame, however ephemeral, even if we have to drink yak urine on Survivor to get it.” For more on this, see my article “Strength in the Face of Adversity: Lessons from the Past” in the June/July 2020 Canyon Country Zephyr.

.

- Advocating for reduction of pollution while ignoring excess consumption as its root cause. “Trying to reduce environmental pollution without reducing consumerism is like combating drug trafficking without reducing the drug addiction,” pointed out Uruguayan American writer Jorge Majfud.

. - Expecting that satisfaction will be gained by going elsewhere, causing endless, futile searching. Psychologists call this “destination addiction.”

. - Believing that scientific proof is the only legitimate source of certainty, even though this belief does not meet its own criterion.

. - Claiming to believe in science while maintaining faith in unproven dreams, such as these identified by Kasser: “that we are travelling down the road of progress and history, that economic growth driven by free and global markets can cure all our woes, that democracy can overcome tyranny, that medicine can save us from disease, that education will keep us in the global race, that the consumption of the goods and services that the system has to offer is the gateway to everything good, and that human nature continues to improve.”

. - Having faith in the power of politics and politicians to solve humanity’s problems despite their failure to do so in the past and their typical disregard for underlying issues of human spirit and integrity.

. - Treating others differently than one would want for himself or herself.

- Presuming that an increase in opulence will cause lasting happiness, despite recurring disappointments. According to Kasser, “The sad truth is that when people feel the emptiness of either material success or failure, they often persist in thinking that more will be better, and thus continue to strive for what will never make them happier.”

Alternatively, a satisfied mind is achieved by holding beliefs, values, and attitudes that are consistent with each other. Kierkegaard called this “single-mindedness,” which is the condition of an individual who is “at one with himself and at one with all about him.” Related terms are cognitive consonance, self-consistency, integrity, righteousness, and purity of heart.

In addition to cherishing nature and learning from it, the single-minded person is appreciative of blessings received, rather than feeling entitled to them and bitter at every perceived deprivation. “Psychologists know that gratitude is one of the strongest predictors of happiness,” wrote psychologist and theologian Richard Beck in his book, The Slavery of Death. On the giving side, the single-minded person gains great satisfaction in bestowing kindness and help to others who are in need. In addition to their upbeat character and resilience during adversity, the traditional Navajos were known for their hospitality to strangers.

Wolfkiller told Louisa Wetherill a story about his family’s amazing optimism and strength as they coped with a severe drought that occurred sometime in the 1870s:

Three more years went by before we had any more trouble. Then the rain did not come in the summer but the wind blew very hard. Our corn did not grow very well, as it needed the rain. The old people said, “We must not talk much about the weather, for we have enough food to last us a year, anyway, and this is much better than it had been at times in the past.” The earth still had a little moisture in it, and we harvested a small amount of corn. We also gathered grass seeds and dug potatoes when we could find them in the canyons. We went on a hunt, but did not get as many deer as we had the year before. Grandfather said we must not complain, as we were much better off than the people of earlier years had been. We still had the sheep, and, while they were not fat, they were still living. They still had a few weeds and greasewood to eat. The winter came, but there was no snow. The next summer there was no rain. Our horses began to die, and we had to gather food anywhere we could find it. I said that I thought it was terrible. Grandfather told me not to talk about it or think about it. “We will not starve,” he said, as someone one had told him that the people at the Big Meadows would give us food when we needed it. “We are not suffering so much yet,” he added.

When another winter came, we had to go to the white people for food. Many of our sheep and almost all of our horses died, but Grandfather was still optimistic. “We are still better off than the people have been at times in the past, as there was now some place to get food from. Back then there was no food anywhere.” We still kept on praying for rain and trying to be happy. Another winter went by with no snow. When the spring came, we had a little rain and planted some corn in the damp places. The summer brought a little more rain. With our corn and what food we could gather, we knew we would be able to go on, and the few sheep we had left would grow fat again. We still had a few horses left and were happy.

From an early age, Wolfkiller learned to appreciate and follow the “path of light” through the teachings of his grandfather and mother. As he matured, he developed an innate sense that he was staying on the right course. The mental faculty that continued to guide him along that way is not one that receives much attention in this modern day and age, but it is something that sensitive truth-seekers might recognize. People such as John Wetherill, who had a Quaker background, would have known it as “Inner Light.” John Collier came close to understanding and describing it:

I will only say: That with the Navajos life truly is an art; that they believe in a universe vital, personal and godlike; that their moral code, which is lived by, embraces our Decalog and adds compassion and charity as the crown of all. They believe that a man’s thought influences the cosmos; and that a venomous thought, or a hate or a fear, draws evil out of the hidden world, acting somehow like a magnet toward evil, and causes sickness and all ruin. Their discipline primarily is a search for joyous thought—for beauty and love; for these draw good from the hidden world, and are efficacious to produce good in the universe beyond man. These are not conventions from which the soul has gone away, in the Navajo’s life. They are realities, as native and central as the breathing of his own body. We have lost these realities; perhaps our race never knew them. Yet we are constituted to know them.

In his summary of the Navajo spirit, Collier was most perceptive in confirming Muir’s contention that the pathway to a satisfied mind leads elsewhere than the accumulation of money and possessions:

So poor they are; and fuller knowledge confirms and extends the first impression of material parsimony and even of a situation which realistically is desperate; and they know their situation, too, and do not try to hide if from themselves, yet the note which their life strikes is exuberance and joy, a winging note and the note of the dance and the dancing star.

How can so rich a flower bloom in a soil so rocky and nearly waterless?

Out in that lonely and hard land of supernal beauty, and within their dearth of the world’s goods and under the deepening shadow which rests on their future, these Navajo Indians practice a complicated art of living. Through this art, whose uninterrupted use comes down through the centuries, although poverty and insecurity go on increasing, the Navajos are not poor or insecure. Thus as one’s knowledge of Navajo life increases, a third impression takes form. The Navajo has created out of his human material a house of wonder. This intangible culture matches the splendor of his land. In terms of life, not of goods, it is we who are poor, not the Navajo.

.

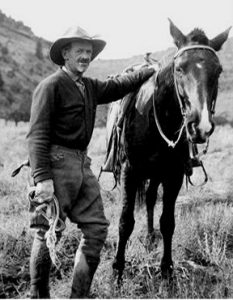

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer. Click here for more articles by Harvey Leake.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Wise and beautiful words to live by. To follow the “path of light” is an ideal for everyone. The philosophy of the saving power of nature is needed so much today.

Very fine and enlightening article.

I see a lot of biased values here. That’s OK, we all have our biases but need some logic, too.

I suggest Mr. Leake and all of us who do like emptier places, wilderness or not, should be grateful that so many people don’t share our bias.

Should all 330 million Americans go looking for solitude at the same time, spreading equally over the 3.8 million square miles of land, we will end up with an average of 87 people per square mile. Now, we would each get 7 acres, but that would not accommodate too much wandering.

And since most of us are more fond of landscapes that have special appeal, we might each end up with less than an acre–and within shouting distance (for good or bad).

Once again, Harvey has conveyed the connection to nature and its resultant spirituality to happiness. This is often forgotten today in favor of the accumulation of consumer goods and material wealth. Happiness is within us, or it is not.

Kierkegaard foretold this to European cultures and his later followers like Camus.

Thanks, Harvey for reminding us of what is really important.

It seems to me that current leaders among the Navajos have bought the idea that happiness is found in greater access to electricity, better roads, and faster internet availability. I can certainly vouch for the idea that there is peace in spending time in nature all alone or with a loved one.