Before Moab, Utah became the absurdly expensive, over-built, over-wrought, contrived and conflicted population center that it is today, it was a different kind of town. Somebody once said, “Moab used to be a hard place to get rich, but it was a real good place to be poor.” True enough then, but that was a long time ago.

No one described Moab’s long ago esprit better than former city councilwoman Christy Williams (Dunton). In 1991, even as Moab was starting to feel its first pangs of transmogrification, Christy succinctly, and perhaps a bit wistfully, put her finger on it. In an interview for The Zephyr, she explained:

‘I hope Moab retains a bit of its funk factor. Not to say I don’t hope that it makes changes, but I think it would be better for Moab to retain its funkiness. Every desert oddball the place seems to attract, I hope it continues.’

She was right. In those days, Moab was sort of an unstructured, free-spirited hodge-podge of individuals, with diverse ideas, interests and origins. Its citizens ran the gamut—from hard rock miners and oil well tool pushers, to hippie boatmen and Abbey Groupies. Hardly anyone was rich, and most got by as best they could. Even bartering was common back then. But somehow it all worked.

For sure, Moab attracted more than its fair share of “odd balls;” some stayed and made a life there, and others just lingered a while and eventually kept going. But to me and to many others, the community was a better place for it. Or at least more interesting. The “Funk Factor” did little to increase the city’s tax base, or drive up property values, but while it offered little in the way of financial stimulation, we were all much wealthier in ways that can’t be measured. (Oh, those Discarded Intangibles!)

Among the Moab passers-by we enjoyed in those days were the peddlers. On a regular basis, there was always some enterprising down-on-his-luck entrepreneur, who was trying to sell something, to anybody who took an interest in his wares. We often saw roadside businesses sprout up, in vacant fields and empty parking lots, selling everything from used furniture to pinyon nuts, to beef jerky. One afternoon I came across this fellow, selling tools out of the trunk of his Pinto. Right there at 100 South and Main Street (where the Hogan Trading Company is now).

But Moab’s most famous roadside merchant arrived without fanfare in the middle days of October 1982 and set up shop on what was once an empty lot next to Miller’s Shopping Center.

I was a ranger at Arches, and on that chilly gray afternoon, my buddy Mike Salamacha and I were in town to pick up a truckload of cedar posts from Plateau Supply on the south end of Moab. (yes…that was considered the south end in 1982). The cedar posts were for a big fencing project that our small crew planned to construct across the north end of Salt Valley at the Arches boundary. None of us had any experience building fence and we were eager for advice.

As we loaded the posts into the park service truck, I noticed a guy leaning by his own pickup, just a couple hundred feet away. He had pitched a large canvas tent, like a revival tent, and was making adjustments to the guy lines. He watched us with casual interest, as he moved boxes from the bed of his truck to the tent. Finally, perhaps because he had nothing else to do, he hopped off the tailgate and walked toward us.

“What’re you guys doing?” he asked with a disarming smile.

I explained our fencing project and he grinned. “Yeah…I’ve strung a lot of fence in my day. A lot of it. Be careful with that wire. When you’re stretchin’ it, don’t let it snap back on you. It’ll cut your face to ribbons.”

Mike and I had paused a moment to say hello and then as we reached for more posts, our new friend said, “Here, let me give you a hand.” He started lobbing the heavy cedar into the truck with an inexplicably cheerful enthusiasm, and in a few minutes we were loaded up.

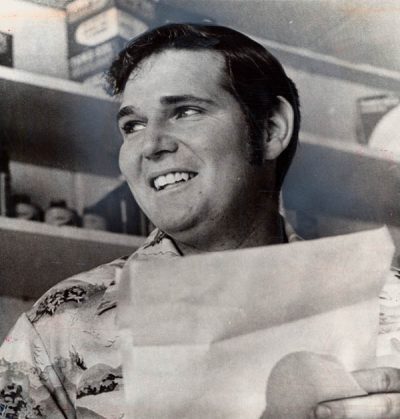

But as we kept lifting posts, I had the vague feeling that I knew this guy, or had seen him somewhere. I was puzzled. We were about to say our ‘thanks and goodbyes,’ when it hit me. His face was familiar because I’d seen it in a copy of Newsweek magazine.

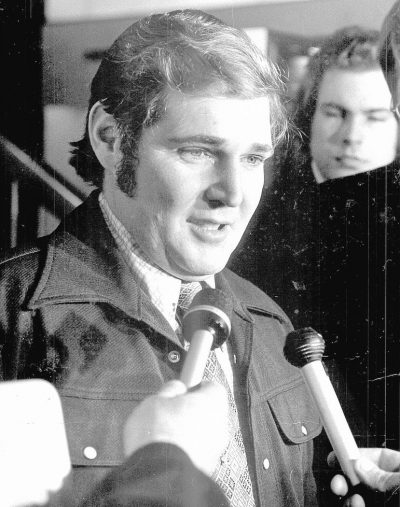

I shook his hand and asked, “You know…you look familiar.” I paused. ” Are you Melvin Dummar?”

His face broke into a sheepish grin and he nodded, “I am…how do you know that?”

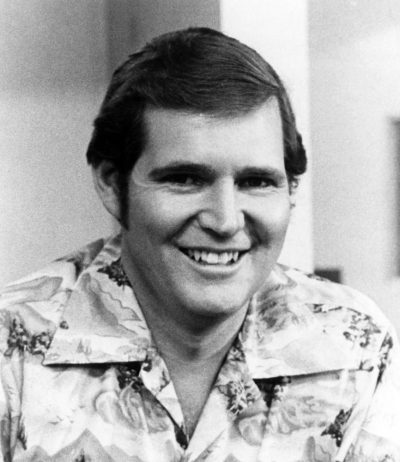

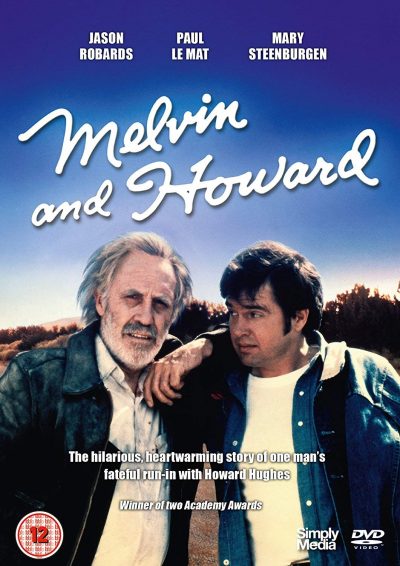

I was almost sure that I had seen his photograph in conjunction with a review of the film, “Melvin and Howard.” The award winning 1980 movie was based on Melvin’s extraordinary story that he swore was God’s Own Truth. But I had to ask again…

“So…Melvin… Did it really happen? Did you really pick up Howard Hughes in the middle of the Nevada desert and give him a ride to Vegas? Really?”

Melvin sighed and plopped himself down on the tailgate, like he was almost too weary to answer the question again. He looked sad and frustrated, but not at all angry that one more skeptic had questioned his honesty. He shook his head, staring at the gravel beneath his boots and nodded.

“I know…it’s a crazy story. But it happened, just like I’ve told it a hundred times. I saw this old bum sprawled out in the middle of a dirt road where I’d stopped to take a leak. He was in really bad shape and I tried to help him out, because that’s what folks like me do…

“I was raised like that. I thought, someday I may end up like him and I’ll want somebody to have a little heart and help me….and I sure didn’t know he was Howard Hughes until we were almost to Vegas. And even then, I didn’t believe him. I figured he was a little crazy. I thought he was just going in there to get warm and maybe bum a free meal off somebody.”

Then I asked about the will. According to Melvin, his desert encounter with Hughes had occurred in 1967. Nine years later, just after Howard Hughes’s death, a handwritten will showed up on the desk of a receptionist at the headquarters of the Church of Latter Day Saints in Salt Lake City (The Mormons). In it, Dummar was a beneficiary to 1/16 of the estate, somewhere to the tune of $150 million. When investigators found Melvin’s fingerprint on the envelope, he came under suspicion by authorities who questioned him extensively. Dummar insisted that the will had been left at his rural service station by a well-dressed man who instructed him to deliver the sealed document to the Mormon Church.

The will was contested and ultimately, Melvin never saw a penny.

He looked up at me and smiled wearily. “It’s what happened.” And then he shrugged. “Oh well, it doesn’t matter.” He glanced at our loaded truck and said, “Hope you guys can get your fence up.”

It was at that moment that I decided I believed every word Melvin Dummar told us, even if it made absolutely no sense.

We chatted a bit longer, I asked him about the movie and what he thought of it. He said it was okay except that “they changed some things,” and he thought Mary Steenburgen, the actress who had portrayed his wife Bonnie, was “stuck up….a little snooty.” Then he added, “but what the heck. She’s from Hollywood. I guess she has a right to be a little snotty.” Melvin didn’t seem like the kind of man to carry a grudge.

We shook hands and I wished him luck. Just before he climbed into his pickup, it finally occurred to me to ask him what he was doing in Moab. “Selling waterbeds,” he explained. “I can give you a really good deal.”

Driving back to Arches, Mike and I talked about our encounter. “I don’t know,” Mike said. “It’s crazy, but I sort of believe the guy.” So did I.

The next week, Melvin made the news again. At least in Moab. This time it had nothing to do with Howard Hughes. Local merchants were upset that Melvin was selling waterbeds out of a vacant lot and was undercutting the prices of the retailers. A couple of store owners had taken their complaint to the county commissioners and on October 18, both they and Dummar got to state their case. Commissioner Ray Tibbetts was sympathetic to the local merchants but agreed that Melvin had obtained the necessary permits and licenses to conduct business and sell his waterbeds. “They still have the factory warranty, ” Melvin said, and he paid the sales tax to the state. But Ray promised to “revamp” the law and asked County Attorney Bill Benge to look into the matter. It was suggested that the licensing requirements might get a lot more strict in the future. Melvin, seeing the writing on the wall, told the commissioners that he “probably wouldn’t be in the water bed business much longer anyway.”

*****

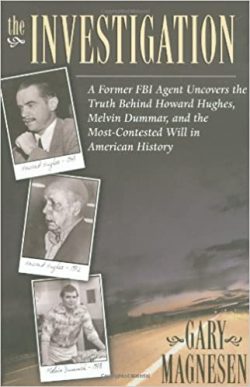

That was my one and only encounter with Melvin Dummar, but over the years, his name would pop up occasionally as he fought unsuccessfully to clear his name and prove the validity of what came to be known as “The Mormon Will.” All for naught. Then in 2005, a book authored by a former FBI agent named Gary Magneson shed new light on the incident in the Nevada desert. The revelations in, The Investigation: A Former FBI Agent Uncovers the Truth Behind Howard Hughes, Melvin Dummar, and the Most Contested Will in American History, gave newfound credence to Melvin’s thirty year claims.

In the late 1990s, Melvin had gone to work for Dean Magnesen, a businessman from Salt Lake City. Over the years, Dean came to believe Dummar’s story; without exception, so had his co-workers. In 2001, Dummar fought his first bout with cancer and expressed the fervent desire to clear his name before he died. Dean was moved by Dummar’s sincerity and contacted his brother, Gary. The retired FBI agent was skeptical but agreed to do some research. Three years later, the skeptic had become Melvin Dummar’s fiercest advocate. Magnesen’s thoroughly researched book offers a convincing defense for Dummar.

For example, it was widely believed that Hughes, the infamous recluse, never left his penthouse suite in Vegas, but Magnesen found witnesses who knew Hughes, who refuted that perception. One of them, a pilot named Robert Deiro, worked for Hughes in various roles for Hughes Tool Company and at the North Las Vegas Air terminal, also a Hughes property. Deiro revealed that he sometimes flew Hughes a couple hundred miles north to a brothel called the Cottontail Ranch. Hughes had an affinity for one of the ladies. On one occasion, Deiro flew Hughes to the ranch but then, the next morning, could not locate his boss. Deiro flew home alone, only to find that Hughes had made his way back on his own. Other Hughes employees acknowledged, belatedly, that their boss had spoken of Melvin and their late night encounter on several occasions. And finally, Magnesen discovered that in 1967, Hughes had purchased an interest in 32 mining claims north of Las Vegas. Access to those claims was on the very road where Dummar found Hughes.

Magnesen and Dummar took the book on tour in 2005 and many readers who had once doubted Melvin’s strange tale changed their minds. It was a comfort to Dummar, though after so many years of ridicule and abuse, partial vindication was bittersweet. Almost three decades had passed since the “Mormon Will” became a topic of debate. In the years that followed, the story followed him everywhere. He couldn’t get a job, he was deemed unreliable, a liar, and even many of his friends in the Mormon Church turned their backs on him.

A year after the book was published, Dummar filed a federal lawsuit, naming William Lummis, the primary beneficiary of the Hughes estate, and Frank Gay, the former chief operating officer of a number of Hughes entities, as defendants. Dummar claimed a conspiracy to defraud him of the $156 million he was entitled to, had the will been validated.

But on January 9, 2007, the suit was dismissed. U.S. District Judge Bruce Jenkins ruled that Dummar’s claims had been “fully and fairly litigated” in Las Vegas in 1978 when a jury rejected the validity of the “Mormon Will.”

Finally, after almost 30 years, Dummar gave up the fight. He rarely mentioned his long struggle again. But he and his wife Bonnie made their own path. He continued to create jobs for himself and wherever he went, exhibited the same gentle kindness and concern for others that he displayed on that dark December night in 1967.

*****

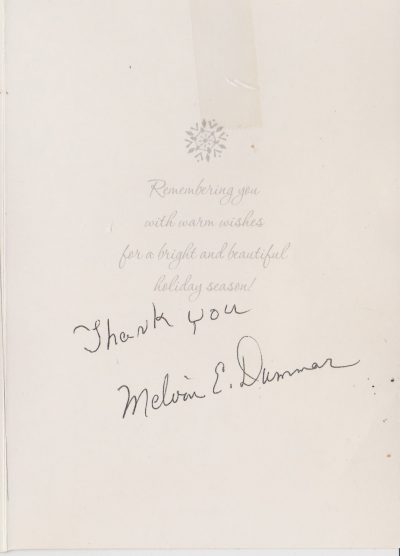

Years ago, I wrote a much shorter version of this story for the print version of The Zephyr. I called it “When Melvin Dummar Came to Moab,” Later, I reposted it on our website. The story resonated with more readers than I expected and I was touched by the concern and support that so many of them showed for Mevin Dummar. One of them was Barbie Dale, a former Moabite who moved to Eureka, Nevada in the 1990s. In 2012, she left a comment for us about Melvin. She explained that Melvin had gone into business for himself, delivering a variety of specialty meats, desserts, and seafood” across Nevada. Every two weeks he came to town. “I believe him,” she said. “He needs some good news.”

Barbie worked at the Owl Club Steakhouse in Eureka and Melvin was a familiar face. “We all knew Melvin was in town when we saw his meat wagon. He and the whole town were on a first name basis. He always had time to talk to everybody in the bar, whether they bought his wares or not. Though he never bought a drink. (Still a good Mormon)…And every year he sent us a Christmas card. I still have it.”

More than anything else, Barbie remembered that of all the people who met Melvin and got to know him over the years, not one of them ever doubted his story. Just like Dean Magnesen and his co-workers. Or Gary Magnesen. People who knew Melvin Dummar believed in him.

In 2017, Nevada Magazine published what was probably Dummar’s last interview, by Shaun Astor. His touching story suggested that the author had come to believe him as well. By now, Melvin’s cancer had returned with a vengeance, and it showed in the photographs Gone was the round, boyish face, and his body was gaunt, almost skeletal. But the image of Bonnie and him embracing, still together after all these years and hard times, showed that his trademark smile had not deserted him.

Nor had he lost his desire to set the record straight. In October 2017, Melvin came across the old Zephyr story that I had written years before and left a comment for us. He wanted to correct some minor errors that were a result of the movie. He noted that he was driving a 1966 Chevy Caprice, not a pickup truck as it was portrayed in the film. Regarding his time in Moab, Melvin wrote that, “I was in Moab selling NEW Water Beds in 1982. I went to court In Moab over Business License practices and WON.”

But more than anything else, he wanted us to understand the kind of man he was. “I was only helping someone that was in trouble,” he wrote, “and I did not ask, nor did I expect to be rewarded for helping him.”

A year later, on December 9, 2018, Melvin Dummar died. He was fighting cancer for the third time, and had recently moved from his home near Pahrump to a smaller house in Beatty. His brother Roy told the Las Vegas newspaper that though the cancer had ravaged him physically, he was still working just a week or two before he passed. He hoped his brother would be remembered “as a hard working guy.”

I’d like to think Melvin Dummar is catching up with an old friend somewhere, in some ethereal desert oasis, convincing the old scraggly gentleman to cut his nails, get a haircut, take a bath, and maybe a change of clothes. The old guy smiles, gives Melvin a pat on the arm and hands him the keys to an obscenely expensive new car.

“This,” he says to Mr. Dummar, “is long overdue.”

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

The Melvin Dummar-Howard Hughes story still has life! it was, of course, the talk of the town in LV. i think there were as many believers as non during the whole affair. Jim’s story gives Melvin a kind sendoff which he deserved.

Jim, what a nice piece of work. I very much enjoyed your updates on Melvin Dummar. I remember the media stories about him and Howard Hughes but your article is the most complete reporting that I have seen. The Zephyr is, in my humble opinion, a real treasure. Maybe it is because I am old enough to remember the old west and your description of it really resonate with me as being true.

Sometime in our lives, we happen upon greatness. You did that. Thank you so much for sharing that moment with us. I remember when his story first made headlines. I never doubted it. I think the man had a great deal of integrity and took a lot of shtuff over it. I’m glad someone tried to make right what had happened with that will. And like you, I will hope the scene at the end will happen. Howard Hughes was a lot of things, but he recognized honesty and integrity. I’m sure he ran into folks without it often enough. So they might truly meet again!

Melvin received assurances from the Vegas FBI office that he would not be arrested if he he came to testify on the Mormon Will case. Years later, the retiring head of that office wrote a book about it. The paper the Mormon Will was on was a custom watermark paper known to be only used by Hughes. The ink and pen used were the only type known to be used by Hughes. None of this information was presented in the Mormon Will case.

Thanks for another fine story, Jim. Interesting and touching too.

Thank you for this wonderful article on the late Melvin Dummar. When I met Paul LeMat at a car show where he was selling autographed pictures from the film American Graffiti, I told him one of my favorite movies was “Melvin and Howard”. He smiled and said something like how much he enjoyed making that movie too, and I got the impression that most fans only asked about Graffiti. I think Jonathan Demme did a wonderful job with the film, paying tribute to the working class, showing Melvin as very hard-working and kind-hearted, without coming across as condescending to the audience. It remains one of my favorites to rewatch and it captures that time in our country when things could still be simple and beautiful, especially in the desert of the southwest. Thanks again for the article!

Great story Jim, Thank you, It made me smile:)! I was very fortunate to have known and loved Melvin Dummar for a very long time and can tell you that his story is true! Melvin continued to do these acts of kindness until the day he passed. One incident that happened during the trial was when he was on a quiet family ride during a snow storm in northern Utah he noticed a person in the bottom of a gully that had crashed his snowmobile, Melvin stopped and went out to help and when he got there he noticed that the man had a compound fracture to both his legs, Melvin went back to his vehicle and grabbed the blankets from the vehicle to keep the man warm until he could get help, Melvin stayed with the man and sent Bonnie to Bear Lake to get help. This was way before cell phones…. Anyway, Thank you for the kind story about my Dad of more than 50 years! He would have given his last penny to you if he thought you needed it.

Ken Bonneau

Your father sound like he was a real Good Samaritan to those in need. I’m sure it was painful to be doubted for his kindness yet he still went out of his way for others.