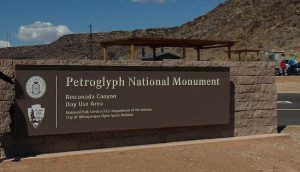

Recently, while most of the country’s attention was focused on the riots in Washington, DC, NBC News reported another disturbing event, two thousand miles west. As a former law enforcement ranger at Arches National Park, so many moons ago, the story of a confrontation between a hiker at Petroglyph National Monument near Albuquerque, and a park ranger was particularly disturbing to me.

According to the report, a Native American named Darrell House was confronted by a park ranger for leaving the designated trail, and then refusing to provide identification. Ultimately the ranger used a stun gun to incapacitate House. It all seemed too incredible to believe, but a video of the incident is hard to ignore.

In the NBC account, House explained that, “I didn’t see a reason to give my identification. I don’t need to tell people why I’m coming there to pray and give things in honor to the land. I don’t need permission or consent…And I don’t think he liked that very much.”

The ranger is heard to say, “You’re being detained because you refused to identify yourself. If you resist, I will Tase you.” And he did.

Another ranger handcuffs House before the video ends.

You can read the NBC story and see the video HERE…

I know the trail. In fact, Tonya and I hiked it just a few years ago, searching for filming locations from the 1962 movie, “Lonely Are the Brave.” There were many people on and off the trail during our afternoon there, and we were way off the beaten path at times. It didn’t occur to us that we were in violation of any law and we certainly would never have thought that our transgressions might get us in that kind of trouble.

It’s true that we are only hearing, so far at least, one side of the story. Perhaps there is more to the event than we know. What I do know, from personal experience, is that one fleeting moment in time can spin out of control, and lead us irrevocably to life-changing consequences that we never saw coming. Consequences that we (and others) sometimes pay for, and suffer far beyond that particular moment, sometimes for the rest of our lives.

I cannot think of a more difficult and heartrending job than that of a law enforcement officer. In the last year, the profession has taken a beating, and some of the criticism was absolutely deserved. Some of it also went too far, labeling and condemning every officer, not just the few who needed to be held accountable. Very few cops are evil. They are all human and make mistakes; it’s just that, in this particular profession, a moment’s bad decision can have profound effects.

What often worries me is the reality that so many law enforcement officers lack the practical experience to make the right life-altering decisions. And this particularly applies to park rangers.

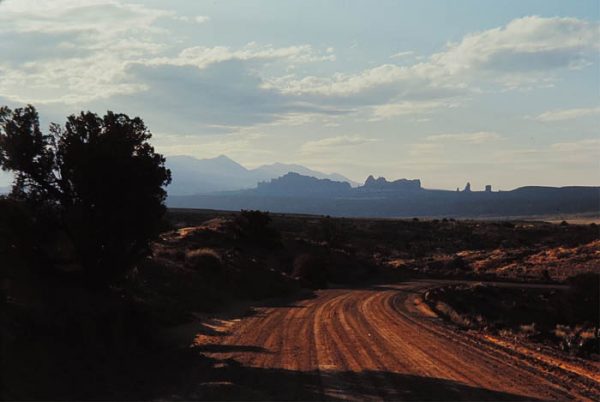

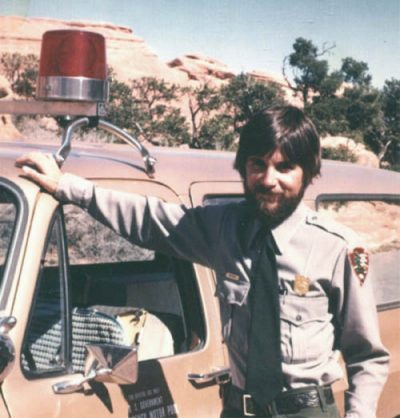

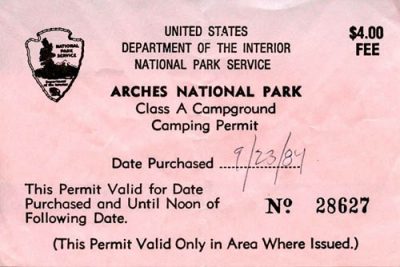

My own law enforcement experience goes way back to the late 1970s. When I was hired as a seasonal ranger at Arches National Park, I was really there for the scenery. Being a cop never crossed my mind. I wasn’t even sure what my duties were supposed to be. So it seemed like a good idea to ask. My boss, Jerry Epperson smiled wryly and said, “A ranger should range.”

So that’s what we rangers did. And while all of us endured the other necessary Park Service chores, like collecting fees and working the visitor center information desk and cleaning toilets and admonishing the tourists for their often almost unbearable ignorance, we still preferred to ‘range’—to get into the backcountry and explore–any time the opportunity allowed us to. To know a piece of land, for no other reason than the intimacy between you that it provided, was the greatest reward of all. We didn’t range for profit. We did it for our hearts and our souls. Not to mention our soles. My thoughts of those “rangering days” are still filled with fond memories of unforgettable beauty.

Still, my job description did include certain law enforcement duties. And so the Park Service sent us off to the federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) for two weeks of intensive training. Every year, we needed 40 hours of refresher training to be re-certified. That usually meant a few days listening to FBI agents tell us about their most horrid cases, complete with crime scene photos and graphic descriptions. To balance the war stories, we endured a few hours of tedious lectures about search and seizure laws. We survived our week of training and went back to rangering and all the reasons we had chosen this profession to begin with. Once we were home, all that “law enforcement” stuff seemed pretty irrelevant.

But fast forward 20 years and I notice that many employees of the various federal agencies are showing less interest in “rangering”. They’re replacing it with a growing zealousness, even obsession, for enforcement of rules and regulations. It is almost incomprehensible. Even fee collecting has become an obsession. It’s not as if they’re working on a commission. Yet, I continue to read stories of park and forest rangers and BLM staffers who spend most of their day looking for violators.

A few years ago, the quest for fees turned to tragedy in New Mexico at Elephant Butte State Park when a state park ranger shot a tourist to death during a dispute over a camping fee. According to a story in the Las Cruces Sun-News, the victim, apparently a tourist in his 50s from Montana, became belligerent with a ranger and refused to pay a $14 camping fee. The ranger attempted to arrest the uncooperative camper for trespassing, the man shoved his hands in his pockets and refused to remove them. The ranger shot him.

After the incident, Parks Director Dave Simon said, “Deadly force is always a last resort” and he added that the “vast majority of park users comply willingly with park fees.” Let’s hope so.

I could relate to the New Mexico incident. I have my own “almost out-of-control, almost deadly force” story to tell.

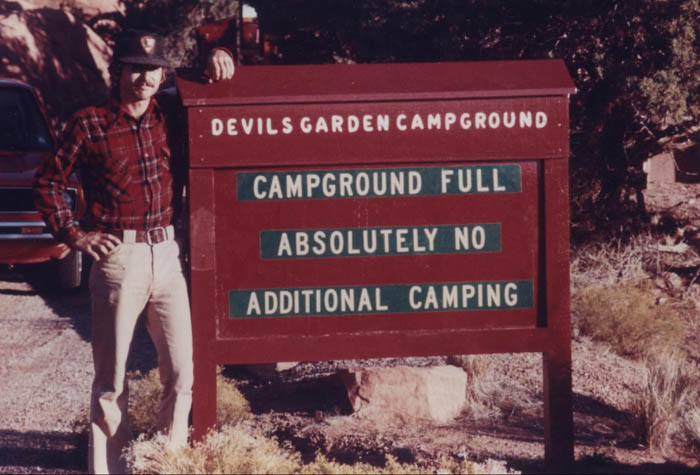

While I always preferred to ‘range’ rather than fulfill my more mundane ranger duties (like collecting fees), sometimes a non-compliant camper would get under my skin. One evening when the Arches campground was full, a couple of young men, perhaps in their late teens arrived after dark and tried to camp illegally in the picnic area. My first encounter with them was civil enough and I told them they needed to leave the park. Twenty minutes later, I caught them again, when paid campers complained that they’d moved into their site.

This time I was firmer and their attitude was icier. They left, muttering as they went, and I knew we’d meet again. A few minutes later I could see their headlights creeping down the Salt Valley Road in search of an illegal campsite.

My self-righteous indignation got the better of me and I went after them. I found their vehicle tracks in Salt Valley Wash. They’d driven off-road and were somewhere ahead of me. It was 11 PM, I was out of radio contact, but determined to confront and cite these violators.

At the time, rangers had not yet become full-time cops but even then we were required to carry our sidearms during night patrols. So I walked into the darkness with my maglite and service revolver snapped firmly in its holster to confront and punish these noncompliant campers.

I found them a hundred yards down the dry wash, already wrapped in their sleeping bags and drifting toward sleep. My arrival was totally unexpected and when I angrily advised them that they not only would be required to leave immediately but that I was also issuing them a federal citation for driving through a natural area, the two young men came unglued.

Both leaped from their bags, screaming. They called me every unkind word imaginable and in such a hysterical manner that I wondered if I was about to lose control of a situation that was barely 30 seconds old. One of them was particularly rabid and finally, as the encounter intensified, he moved toward me in a way that definitely felt threatening.

I was, in fact, scared to death.

I took a step backward and placed my thumb on the keeper of my gun holster. The young man saw the move and stopped. Then he screamed at me, “You take that f—king gun out of that f—king holster and I’ll take it and shove it up your f—king ass!”

We stared at each other for five long seconds…

And I reflected on his words. I decided that, in fact, he was absolutely right. Even if I took my gun from the holster, I could never shoot the man dead for illegally camping in a national park. And on the other hand, this young fellow, in his current frenzied state, might very well take the revolver from me and kill me. I could almost see the headlines in next week’s Moab Times-Independent:

SEASONAL RANGER AT ARCHES NP SHOT

BY ILLEGAL CAMPER…

FUNERAL SERVICES ON FRIDAY

“Okay,” I said, taking a deep breath. “I’m going back to my patrol cruiser. I want both of you out of here in 30 minutes.” Retreat seemed like the most viable option. I backed away slowly, turned and walked back to the road. Had they been running up behind me I would never have heard them—the sound of my heart pounding in my ears was deafening.

I sat in my patrol car for 20 long minutes, still shaken but happy to have my ass intact. Finally, incredibly, here they came, packed up and in their car. One of them had calmed appreciably and I handed him the citation. He actually thanked me. His friend, however, was still out of control and kept slamming his fists into the headliner of his friend’s roof. I imagine damage to the vehicle surpassed the $50 fine.

I drove back to the Devils Garden, to my residence, slept poorly and wondered if I’d done the right thing. Had I been a coward or a wise man? I decided that for once, I’d been the latter. I never came anywhere close to a confrontation like that again. Life, whether theirs or mine, was not worth the risk over an illegal camping infraction.

***

At Petroglyph NM, the details behind the recent stun gun incident have not been fully revealed. Perhaps there are extenuating circumstances. A spokesperson for the NPS told NBC that all law enforcement “officers receive extensive law enforcement training.”

But that might the problem. In so many national parks, where serious law enforcement issues rarely occur, its rangers never experience the kind of on-the-job training that rangers need to fully develop those skills. A couple weeks of law enforcement school training are lost if the skills are rarely needed. That kind of training has no chance to become muscle memory, when it’s rarely implemented in any real-life situations. The ability to quickly and definitively decide whether to kill or harm someone in the course of your duties needs to be a reflex–and generally it should be the reflex toward restraint and not toward jumpy action. But, for the most part, rangers don’t want to build that muscle memory, or gain that kind of practical experience. They never wanted to be 24/7 cops to begin with. I certainly didn’t. And the ones who did sign up to be land-cops…well, they’re the biggest problem of all. It’s a conundrum that is difficult to resolve.

Earlier, I mentioned my time at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center. Our first instructor asked each of us what our most serious law enforcement issues were. When we told him, off road travel and picking flowers, he asked, “Why are you here?” We said we didn’t really know either.

If the Park Service intended to prepare us for critical situations like the ones I’ve mentioned, then that training was a waste of time.

In the end, I would guess that the situation at Petroglyph National Monument can be blamed on the ranger’s lack of practical experience, magnified by fear and adrenaline, and the rapid way uncontrolled events can unfold. I doubt it reflects entirely on the moral and ethical character of the ranger who discharged the stun gun, or the man who allegedly provoked him. Both were in a situation that escalated too quickly.

Still, to me, it’s a story that didn’t need to happen. There’s more to Life—- like staying alive–than freaking out over a hiker who wanders a bit off the trail. It seems like this particular Ranger has forgotten the need to “range.” He was wound too tight, like so many of us are these days. Maybe if we all take the time to ‘range’ a bit more, and fret a lot less, we’d stop having so many of these out-of-control altercations. Maybe the entire country should go ‘range’ for a while. It would surely be an improvement over our current state of chaos.

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I can still remember one of my climbing friends telling me that he had seen Valerie conducting a car stop in Tuolumne Meadows in about 1980, as she was telling an irate speeding tourist, “I am a Federal Officer and you will do whatever I tell you.”

A few years ago some California friends and I returned to our vehicle in Butler wash after a hike to ruins on Comb Ridge to find an official looking notice on our wind shield. It said that we were in violation of some BLM regulation. I was amazed and some what shocked that this had happened. I took the notice to the BLM in Monticello and showed it to a person in an office that I assumed had some official responsibility for enforcement of BLM regulations. Unlike Jim Stiles I did not keep notes of whom I talked to. However, the person expressed surprise when he looked at the notice. He said something to the effect that BLM rangers were not yet authorized to leave such notices on vehicles. He then asked to keep the notice. I figured it would then disappear down a rat hole and refused to give it to him. I think this is an example of a Ranger thinking that enforcement of BLM regulations was what ever that Ranger wanted.

Jim’s story of the confrontation in Arches is one that every Ranger should study. I have also read the story about the event in New Mexico and was distressed to see the way that man was treated. I had previously read about that site and how important it is to Native Americans.

As usual i have a comment (love hearing/reading the tales!). Grandson-in-law retired as a Sgt from Metro in LV. They were working Gang Detail. He’d take his life in his hands to haul them in, be writing out the report as they sashayed by him on their way out!! Pretty frustrating. Law officers/rangers have to have lots of patience besides human knowledge. As I’ve often told police bashers,, these people have maybe a nano second to decide on a life or death matter sometimes. Not all personalities fit in law enforcement of any kind. But to defund the police is a lesson in idiocy.

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

James Madison, Federalist 51

Rules, and laws, are important for society, especially since we are not angels. But in our modern system, where government has a near-monopoly on force (and rightly so), we should be cautious about what laws we create. In the end, any law–and enforcement of that law–could lead to “justified” deadly force.

Sadly, you are incredibly misinformed. Had you watched the full video, you would have seen that the ranger bent over backwards to avoid a confrontation and likely had every intention to issue a warning. Even if park rangers left, someone would still need to enforce the law in parks. It would then likely fall to a local sheriff’s department, which might enforce murder and drugs, but likely is going to be disinterested in whether people cut down trees, deface archeological sites, poach wildlife, pay camping fees, litter, etc. You bemoan fee collecting, but fees help parks make improvements despite budget restraints. Fees also can help to regulate use at parks where visitation exceeds capacity. While I don’t know the situation at Arches, rangers elsewhere serve in an EMS, wildland fire, structure fire, and search and rescue capacity. I have know numerous rangers that had a passion for the outdoors but also saw the critical need for law enforcement capacity at parks.

To better explain his perspective, it might have been helpful if Mr. Pickford had — in the interests of full disclosure— identified himself as a paid National Park Service law enforcement ranger…JS