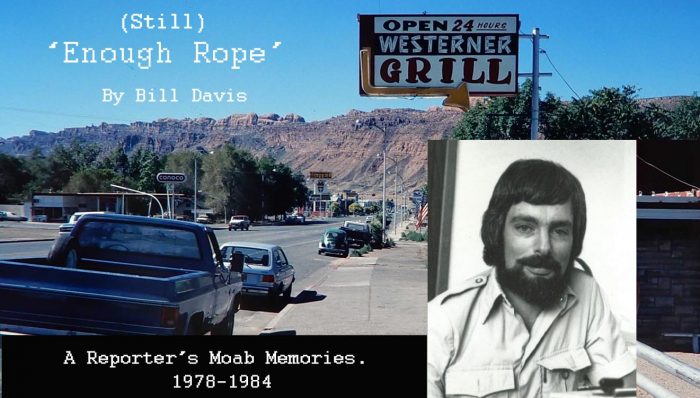

The local high school kids called it PCP: Plane Crash Pot.

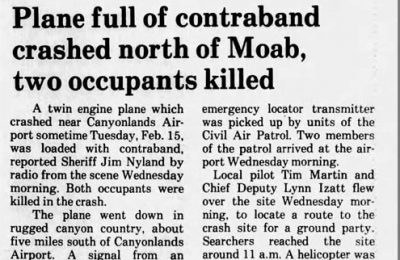

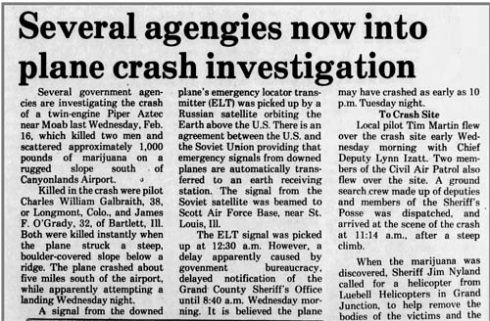

The source of the PCP was, logically enough, a plane crash. The craft went down late the night of Tuesday, Feb. 15, 1983, about five miles south of Canyonlands Airport.

I first learned of the crash early the next morning from my usual spot news source—the pocket scanner I carried constantly during my years with The Times.

The chatter about a plane crash woke me up in a hurry; airplane crashes were big news at any small-town newspaper, although surprisingly common around Moab. During six and a half years I covered there were five, if memory serves, which seems like a lot. Some of the radio traffic indicated the plane had something illegal aboard.

Unfortunately, that morning was a Wednesday—newspaper production day—effectively locking me, and the rest of the staff, into the office until late afternoon. That particular limitation on several occasions drove me nuts; there was no way I could leave before the paper was out, even if space aliens kidnapped the mayor (which wouldn’t have necessarily been a negative during certain administrations).

Throughout my tenure, I maintained an every-sparrow-that-falls attitude toward news gathering: If something happened, I had to be there, and most of the time, was. (I never recommended this approach to my students when I was teaching journalism; it leads to burnout, as I discovered toward the end of my time in Moab).

I was like an old-time firehorse; if the steam-powered pumper left the station I was by god not going to be left in a stall—except on production day, when I would be (ahem) champing at the bit.

I knew we had to get something into the issue, even if from a distance, or wait another eight days for the next one to be distributed, which was unthinkable.

“I know,” I thought, “I’ll have the sheriff’s office dispatcher radio Jim, who I know is out at the crash site, and he can give me some details.”

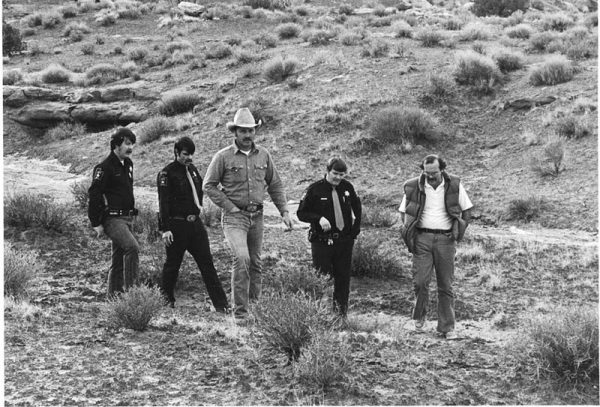

Here we must pause the narrative to introduce Jim Nyland, who had replaced Heck Bowman as Grand County sheriff in 1978, not long after I arrived in town (With voters demonstrating unusual good sense, he went on to serve approximately forever, until 2011). I hadn’t had enough time to get to know Heck, but over the years, I came to know Jim well. He had modernized the office, hiring new deputies, putting them in uniform, and, in general, expanding all the department’s functions.

He had also repeatedly demonstrated a belief in the importance of truth, and was the most honest elected official I’d ever met (With a few of our local politicians, if they said the sun was shining, I’d go outside to check.) In this case, however, he seemed uncharacteristically recalcitrant.

“1-T-1, Moab,” I heard the dispatcher call him over the scanner, “I have Bill Davis on the phone, and he wants to know what kind of contraband was aboard the plane.”

A long pause followed.

“Moab, 1-T-1, just tell him. . .contraband.”

Great. Elephant tusks? Diamonds? Cocaine? Illegal aliens? I can’t just write “contraband” in a front-page story; it would look stupid. I asked her to make the request again.

Another long pause.

“Just tell him. . .contraband.”

What the hell? Obfuscation was not Nyland’s style.

Frustration grew. I suspected it was probably pot, but I wasn’t about to make assumptions, having in mind the WWI vets fiasco of three years earlier (see last issue), so I wrote up a sketchy story that did, indeed, say the twin-engine plane was loaded with “contraband,” which, Jim had emphasized, had been flown out in by helicopter via a sling. I continued to fume about inadequately covering a big story.

Jim, however, proved to be correct in his caution about putting too much information over the airwaves, and his emphasis on the helicopter’s sling load. He appreciated what I did not, that many people in town beside the local reporter had scanners, and word would get around quickly, which it obviously had by that night.

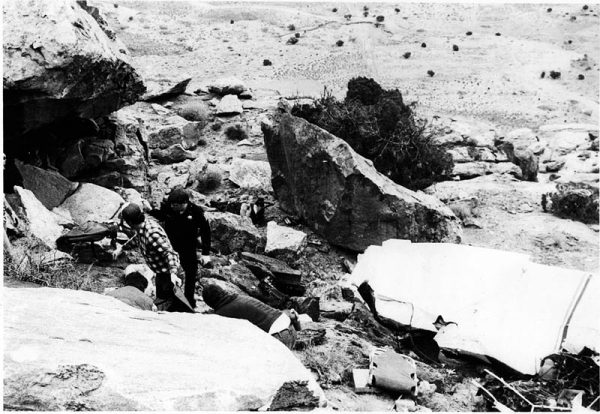

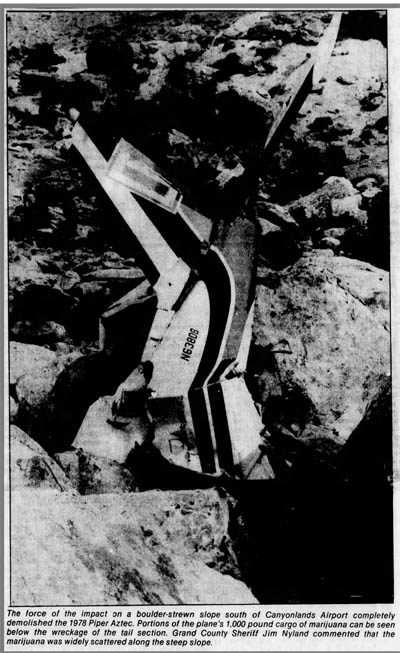

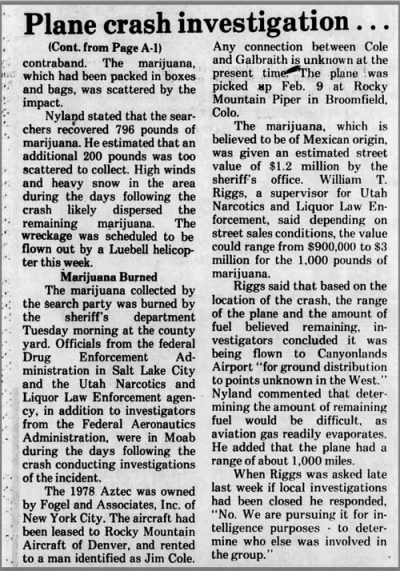

The contraband, it turned out, was 1,000 pounds of Mexican marijuana. Deputies and members of the sheriff’s posse spent the day collecting the weed, which was scattered across a rugged field of massive boulders below a ridge top, along with the two occupants of the fragmented Piper Aztec (Chief Deputy Lynn Izatt grimly described the scene as “an anatomy lesson”).

By the end of the day, deputies and posse members had collected 796 pounds of grass, the remaining 200 pounds reported to be “too scattered to recover,” depending, of course, on one’s motivation: tired deputies after a long day of collecting hundreds of pounds, with darkness and foul weather approaching, versus local entrepreneurs and pot aficionados entertaining visions of free dope, even if it was a couple of ounces picked up with tweezers.

And motivation was obvious as I listened to the scanner that evening. Deputies on patrol near the crash site spotted and chased off numerous vehicles and their occupants throughout the night. However, some seriously motivated visitors obviously got through on foot, sparking the later arrival of PCP in Moab. I debated taking my ’69 Jeep CJ5 out to the area, but figured I would have spent a cold, snowy evening wandering fruitlessly around unfamiliar trails, with little chance of getting a usable photograph, so I stayed home in front of the wood-burning stove, still fuming about missing a major story.

By the next morning, I had determined that if I couldn’t actually witness the event, I would research the living hell out of it and produce a story so filled with details it would make my readers’ eyeballs hurt. For once, I wouldn’t have immediate deadline pressure, so I could afford the time to dig. Keep in mind this was long before computers, the Internet, and free long distance (Hell, nowadays, no one even knows what “long distance” was. Hint: It was expensive.).

One of the first details I discovered was the 1978 Aztec was owned by a New York firm, and rented out by a Denver company to a man whose name did not match the identity of either of the victims, a 38-year-old Longmont, Colo. man and a 32-year-old man from Bartlett, Ill.

The rental had been picked up at a Piper dealer in Broomfield, Colo. When I contacted the company, the man who answered sounded a bit twitchy about one of his rentals fragmenting itself and a half-ton of pot on a Utah cliff. He emphasized repeatedly (and understandably) that they had no knowledge of where the craft was going and what the renter had been doing, only that he had shown a valid pilot’s license and flown out on Feb. 9; that meant there was a gap of six days between the rental and the crash, plenty of time to go—somewhere—Mexico, say.

In the first, sketchy story, I reported the plane’s ELT (Emergency Locator Transmitter) signal had been picked up by a Civil Air Patrol unit flying over the area. That was true as far as it went, but there was more to the tale.

The original ELT signal had been picked up—wait for it—by a Russian spy satellite. Turned out the governments of the Soviet Union (which it still was until 1991) and the U.S. had for years quietly assisted each other when their spy satellites, handily orbiting over each other’s territory, picked up ELT broadcasts; a message, including location details, would automatically be beamed to a ground station in the other country. I got this interesting detail from an officer at Scott Air Force Base near St. Louis, Missouri, who cheerfully explained how the cooperative agreement worked.

As a side story, this fact, included in my follow-up, set off one of Moab’s more colorful characters—Maggie Stryker. Maggie was, in a phrase, a piece of work. She was ancient, had an interesting past (I’m a fine one to talk), and was one of the most foul-mouthed human beings I ever encountered (Considering, in the rock band, none of us ever completed a sentence without one or more F-bombs, that’s saying something). She lived in an apartment upstairs from Ray Tibbetts’ clothing store at Main and Center, from which she could apparently see everything that ever happened, anywhere.

Maggie had, throughout my time at The Times, been the source of numerous outraged letters to the editor and phone calls, which, for some reason, I seemed to always field.

Example: Something Adrien Taylor, my co-boss, had included in her Many Trails column once triggered Maggie, who told me over the phone she was “going to come down there, drag Adrien out into the alley and beat the living shit out of her.” She didn’t.

Example 2: I was in the office preparing for a Tuesday night city council meeting when the phone rang. It was Maggie, again, who demanded, with obscenities, that I immediately investigate the UFO landing “near the dump road.”

I walked out of the office and looked east into the darkness toward Sand Flats. Yep. There it was, one of those UFOs cleverly disguised as car headlights. That was Maggie.

The spy satellite info sparked another angry phone call, during which Maggie railed against the blankety-blank Commie Russian bastards being the first to know about an expletive plane crash in Grand County, and why didn’t the condemned sheriff’s department have someone listening to that kind of deleted radio all the time, and on and on.

Interestingly, despite our many contacts, I never met Maggie in person—which was fine by me.

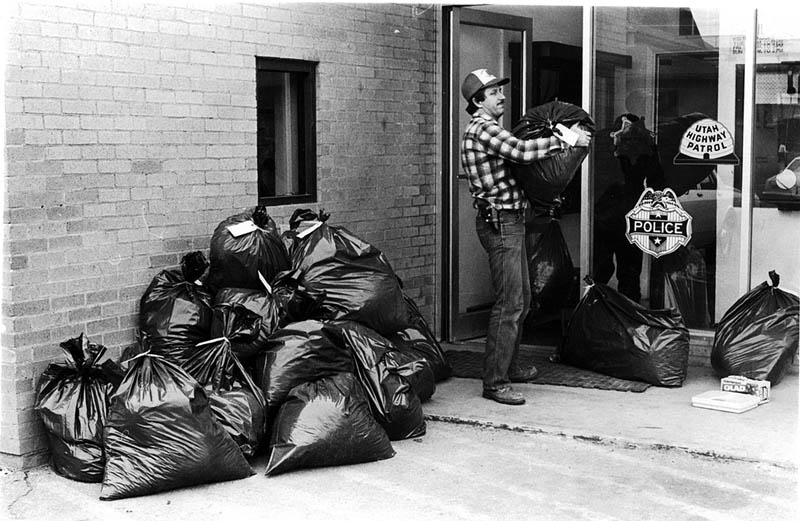

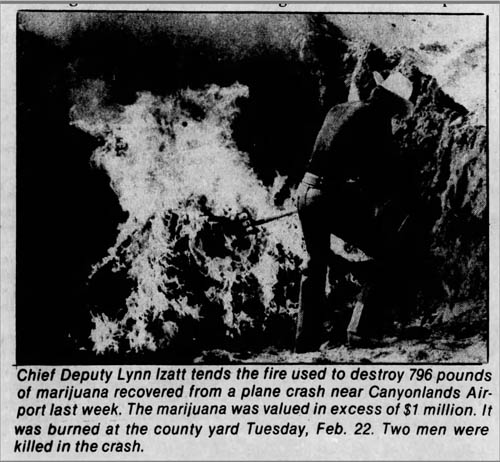

Meanwhile, back to the dope: The sheriff’s department didn’t exactly have room to store hundreds of pounds of pot, so the decision was made to burn the stuff (save a sample as evidence) the following Tuesday at the county yard, an event I was invited to cover. At least now I would have some of my own photos to add to those of the crash scene we borrowed from the department.

As the S.O. didn’t have an official vehicle of sufficient capacity to haul the marijuana, Deputy Steve Brownell and his private pickup with camper shell were drafted. Steve allowed as how he was a bit discomfited hauling nearly 1,000 pounds of contraband, valued by Jim at $1.2 million, south of town to the yard unaccompanied, but he arrived at the site safely. After the unloading, Steve’s slacks were so coated with the stuff the lower legs looked green, and had probably become the most expensive pants ever seen in Moab Valley.

I am here to tell you that 800 pounds of loose marijuana makes one heckofa bonfire. Izatt, wielding a pitchfork, would toss some into the air, where it would explode in flames, while exclaiming, “One thousand dollars!” with each forkful.

Several of the deputies helpfully suggested that the still-long-haired, hippie-looking reporter might want to stand downwind in the fire’s smoke plume. I pointed out that they had pretty much ruined that experience by adding an old tire and diesel fuel to the blaze. I was wearing contacts anyway.

So I had my detailed after-the-fact story, which can be seen at the University of Utah’s newspaper archive here, if you’re interested: https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s64r2cfg. The sketchier first story is in the preceding issue.

All those details eventually paid off. The piece won Best News Story of the Year for 1983 from the Utah Press Association. And, because I can’t figure out any other place to mention it, that same year I won Best Column for Enough Rope. I had copies of the awards in my office the whole time I was teaching in California, and they’re still on the basement den wall. I’m proud of those things.

A week or so after the second story ran, I got a phone call from an attorney representing the family of one of the crash victims.

“I heard some marijuana was found on the plane,” he said, sounding as if he envisioned a baggie in the Piper equivalent of a glovebox.

“Some,” I said.

“How much?”

“About 1,000 pounds. The sheriff’s office recovered 800.”

The line went dead.

As a point of interest, the permissible “cockpit weight” of that era’s Piper Aztec was 1,200 pounds. The total capacity of the plane, including luggage, was 2,000 pounds, so with two people aboard, that thing must have been stuffed to the gills.

Long after the crash investigations concluded and the stories, written, I was yarning with Tom Arnold, “Tom-Tom” of the notorious, and much-discussed “Volkswagen Museum,” between Moab and Spanish Valley, where I got parts and advice for my Thing (I know, I know). I knew Tom was an experienced pilot, having flown PBY patrol seaplanes in World War II, and river-running shuttles and other light-plane trips in the Moab area.

I was curious what, exactly, caused the pot plane crash. The pilot obviously had planned to land at Canyonlands Airport late Tuesday night to offload his cargo. I knew that pilots coming in late could activate the runway lights as they approached by keying their radio mics seven times on a specified frequency, which would light the runway for a half-hour, if I remember correctly. The airport’s beacon, which was elevated on a tower, remained lit all the time.

Tom explained that, when landing at night on a lit runway, if you saw a complete set of lights on both sides, you knew no solid objects were between your plane and a safe touchdown.

He theorized that the pilot of the pot plane, to avoid attracting attention, chose not to turn on the runway lights, but rather lined up using the always-lit elevated beacon.

The difference in angle would mean that, while there was nothing solid between the plane and beacon, there might be something truly solid, such as a rocky ridge top, between the plane and the ground, which would be invisible in the darkness. The irony is he probably could have landed to bright lights, a parade, and marching band at that time of night without attracting outside attention.

This proved to be one busy news week.

In addition to the pot plane crash, the body of an unidentified murder victim was found near the Three Gossips in Arches National Park. Jim discussed this case in a previous issue of The Zephyr.

I was there when Izatt, three deputies, and County Attorney Bill Benge investigated. The victim, who had been in place for two to three months and had received some attention from the local wildlife, was never identified, even after the assistance of the State Medical Examiner’s Office, and later, the FBI lab in Washington, D.C. was requested.

The victim’s hands were shipped to the lab to obtain fingerprints, but were too desiccated to rehydrate. Lacking victim identification, in this era of no DNA-matching ability, solving the murder was virtually impossible without a tip or confession. None was forthcoming and the mystery remains. To this day, I sometimes find myself wondering who he was and what he did to earn an execution-style .22-caliber departure.

I used to occasionally tell this story to prospective journalists. A student in one class refused to believe that just the hands would be sent to the FBI, minus the body. Years later when she was a wire service reporter, I received this note:

Dear Bill:

You were right about the hands.

Love,

Hilary

Afterword the first: During my time there, I had extensive conversations with another well-known Moab character, who, like Maggie, I never met in person, but was a good deal more pleasant: Sog Shafer.

My first encounter with him was at a distance, causing me to grouse to Times officemates: “I just about hit a pickup head-on on Main St. The old guy was all over the road, and acted like he didn’t see me. He must have been blind.”

Coworkers Beth Heggeness and Annette Kearl, after asking what color the truck was, looked at each other and said as one: “Sog.”

I learned what everyone else in town already knew: Sog was, indeed, elderly and very nearly blind, but still drove his truck on errands, directed verbally by his grandchildren which way to steer, an approximation at best.

Other locals were aware that when you saw the old green (Kris remembers it as blue) Chevy pickup headed your way, you got out of the way; it was not an issue. I also quickly adopted this folkway.

Sog owned several rentals in town, and frequently placed ads for them in the newspaper via phone. I occasionally took the calls and always ended up being entertained at length by his stories of old Moab. He loved to talk and I was glad to listen. And he never swore.

His name, he said, was an abbreviation for sorghum, of which he was apparently a fan in his youth.

Afterword the second: Scanner listeners may note my use of the identifier “Moab,” in sheriff’s dispatch radio messages. This was later changed to “Grand County,” but at the time of the crash it was still “Moab.” The change reflected who was paying for the operation. Everyone, city cops, highway patrol troopers, ambulance and fire units, suddenly started using the lengthier title. I have no idea what is used currently.

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Good stuff… After a life lived in touch with Moab, rural Arizona and odd happenings in general I seem to remember a large twin engine delivery that took place in the desert east of Hanksville, only discovered because the plane was left at the remote dirt strip as a cost of doing business. Can’t find any mention of it now.

Easier to find mention of the glory days of the once ghost town of Jerome, Arizona and its “hippie” inhabitants.

https://apnews.com/article/e5f2f033a164cb15c2bd9771fc4b9e0b

Never far from a good story in the West.

heh: the short note from Hilary about the hands. and the previous comment mentions Jerome. in the occasional fit of … ¿craziness? loonassy? whuddever … my wife considers re-locating to Jerome. oh, good and fun-to-read story by the weigh!

Thanks for the story. It brought back many fo d memories of that period of time in moab and its colorful characters and history.