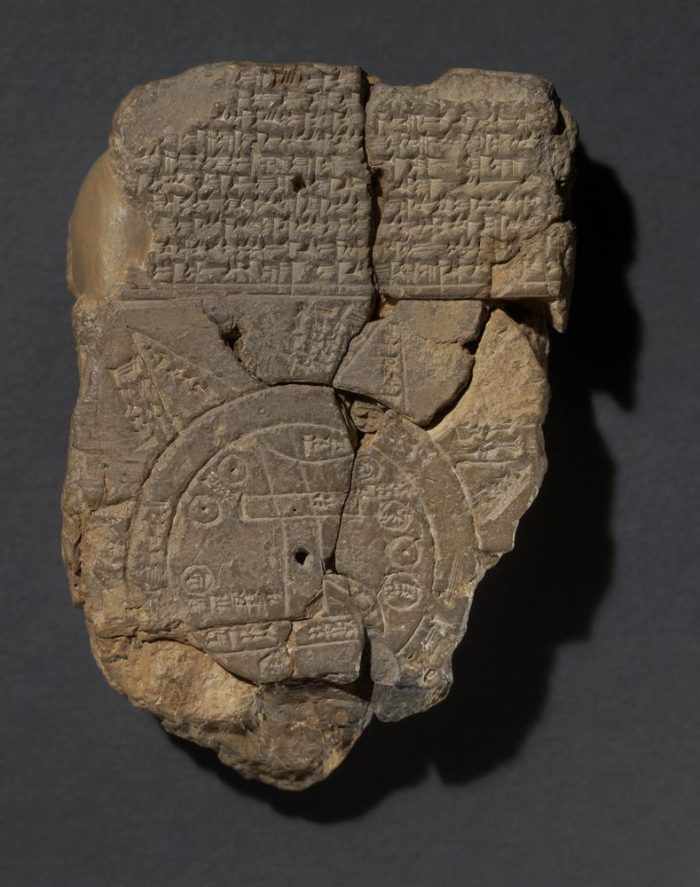

The oldest surviving map of the world—the Babylonian Imago Mundi—circumscribes a landmass between the Mediterranean and Caspian Seas. The world it describes is only as long as the Euphrates River. At its center lies the city of Babylon.

To the mapmaker, chiseling in the 6th century before the Common Era, this was the world. The areas beyond Mesopotamia are dismissed, even as they are acknowledged, vaguely, with triangles beyond the known world’s oceanic boundaries.

To the modern eye, it seems like a child’s view of cartography. The world, according to such a limited map, is where I live. It comprises only the places I’ve seen, and perhaps a few others I’ve been told about. It would be like someone in Memphis vaguely outlining the primary urban centers between the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Michigan, drawing a circle around them, and calling that “the world.” What use is that?

And yet. I feel fond of that chiseled Babylonian map. I look at it again, and then again. This primitive attempt to explain “home”—the cultural and mythological center of the world—within the context of the mapmaker’s own limited human knowledge. Somewhere out there, beyond those intimidating seas, were other worlds. Someone had told him that. And what did he imagine of them? I would like to know. I would like to ask this mapmaker a thousand questions. He’s made such a lovable map. I wonder whether he was thanked for it, in his own time.

Lovers of maps. Yes, we quietly exist in this technological era. The sort of peculiar person who would own a magnifying glass without irony. A connoisseur of compass roses. You don’t even need to say now that you like to study “old” maps. What’s an old map, when life is so paperless? All maps are old maps.

But I would think it’s the rare map-lover whose taste for maps is truly indiscriminate. Like that Babylonian cartographer, we each tend to treasure the places we know—or the places we knew once, or maybe hope to know one day. Often we love the places we wish we could have known. If only.

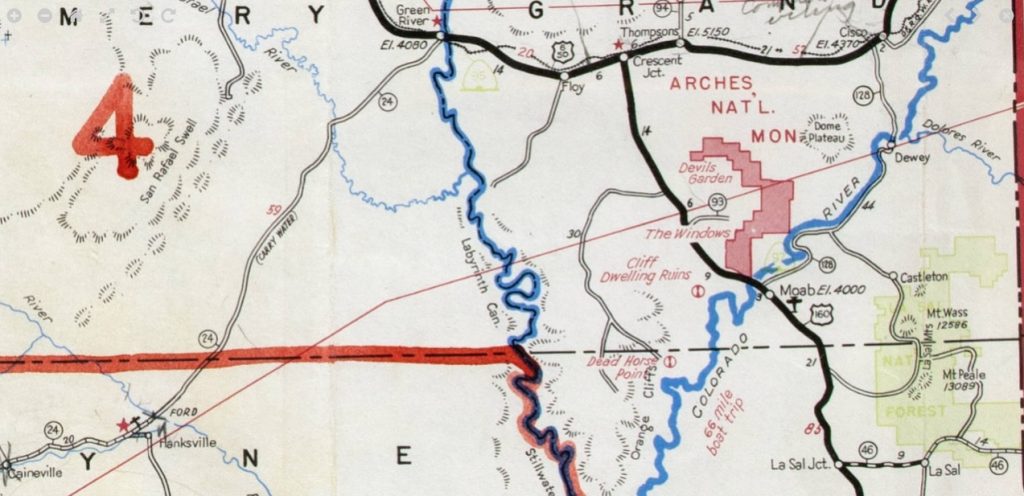

Thousands of map archives have been compiled over the centuries, in libraries and museums. Increasingly, they’ve become digitized—which is a bittersweet delight for those of us torn between convenience and romance. Recently, I spent a few hours looking through a digital archive of Utah road maps throughout the 20th century. It was astonishing to observe the fits and lulls in the development of some of the least known areas of the country.

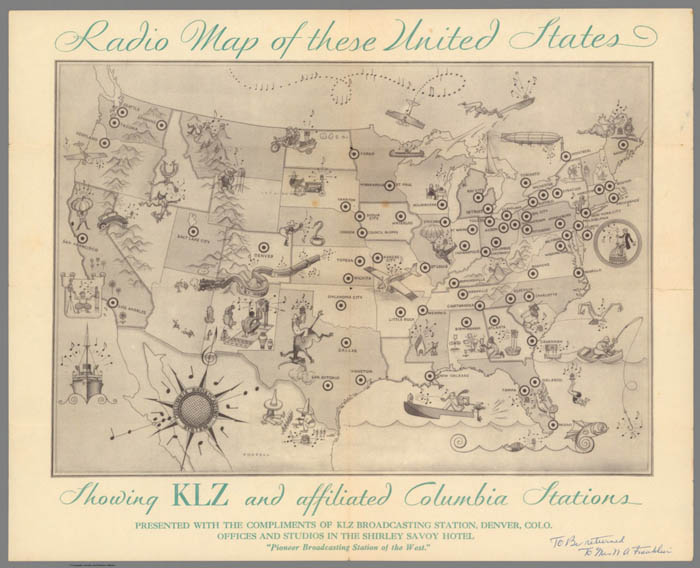

A road map is a fascinating thing. We think of them as a 20th century invention, but Europe was spanned by a dense network of roads as far back as Roman times, and they too were mapped. Many of those roads still exist, as the foundation for modern highways. But when we say “road maps,” we tend to mean those of the last century.

Modern road maps are altogether different from earlier maps. They presuppose a certain speed of movement—a speed that increased rapidly as the roads and cars improved. By scale alone, usually encompassing the borders of an entire state, a road map anticipates that you will be covering serious ground. And they have to be updated continually—yearly, at least—to avoid mishap and confusion amid the speed of development.

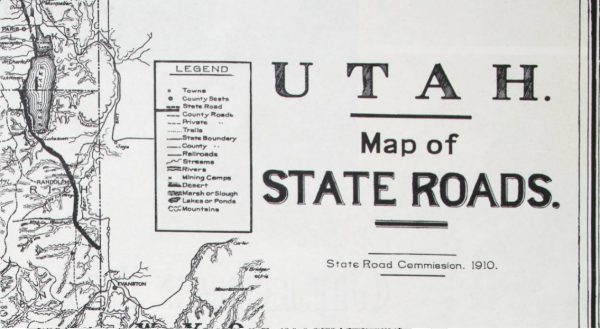

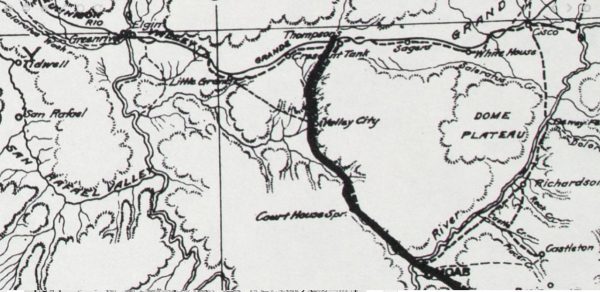

The first road map archived on the state of Utah site dates to 1910, when there were fewer than 150,000 automobiles in the entire nation. Utah’s official road map that year didn’t differentiate between paved and unpaved roads. The delineation would have been pointless. Outside the downtown streets of Salt Lake City, the entire concept of road-paving was pure futurism. Rail lines still traversed and connected the state with greater fluency than the patchwork of state and county roads. Many “roads” of the time were no more than rutted two-tracks and horse trails. To make the bumpy trip from the D&RGW rail station at Thompson, Utah down to one’s home in Monticello…just imagine. It would have required a patience and fortitude far surpassing modern abilities.

And, like all old maps, that 1910 map contains a thousand questions for further research. Blanding, Utah, for one, appears on that 1910 map as Grayson. Its name didn’t change for another four years. More questions–why did the roadbed alter at the junction of Thompson and the Moab road? Is there any remnant of all the unincorporated towns that “fell off” the map as time went on?

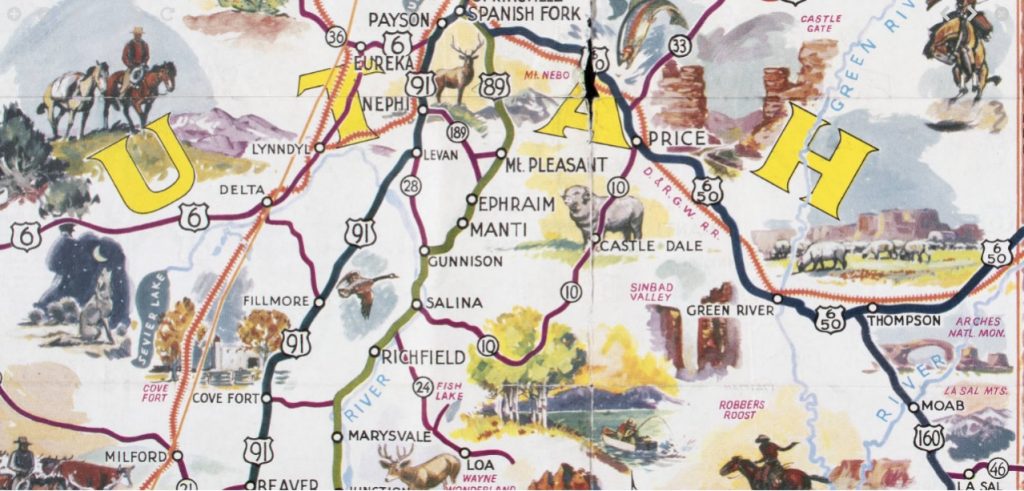

Tracing the road maps of Utah throughout the next few decades, you witness the increasingly heavy footprint of miners and farmers, the imprint of a flow of goods across the highways. By the mid-1930s, an unimproved trail appeared, connecting tiny Hanksville to the considerably tinier Hite. The future highway 95 extended tentatively from Blanding toward Natural Bridge. The two wouldn’t connect, thanks to the Hite Ferry, for another decade.

In 1940, the state included a cheerful pictorial map on the back of its official brochure, an acknowledgment that these maps were increasingly designed for tourist traffic. Then, beginning with the Eisenhower years, an explosion of investment. New roads. New paving. The toll ferry at Hite became a bridge. Glen Canyon Dam, of course, forever altered the mid-bottom of all the ensuing maps. Instructions to “carry water” along certain highway routes, including highway 24 from Hanksville to Green River, disappeared with time. Forty miles wasn’t what it used to be. Suddenly, the suggestion—and eventually, the completion of Interstate highways. Each change made the ground easier to cover. The landscape blurs at such speeds.

Distance itself isn’t what it used to be.

From the modern perspective, it can feel as though there is no more of this world left to discover. It’s all been charted and plotted into tedium. All the relevant scenery is dutifully marked for…well, we still call it “exploration,” though it isn’t. All the trails are signposted. All the mysteries, solved. Maps don’t mumble and meander off the edges anymore, with unknown lands to be described some other day. To find that kind of mystery, you would have to travel against time.

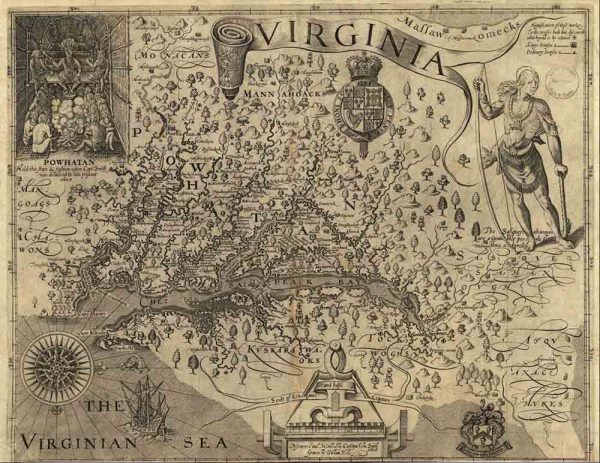

The older the map you’re studying, the more it is a record of the limitations of human knowledge. On his 1611 map of Virginia, for example, John Smith used small crosses along the river banks to show the extent of his own explorations. Beyond those crosses, his map—which was the best map of the territory at the time—was conjecture, its terrain based on the hearsay of his native sources.

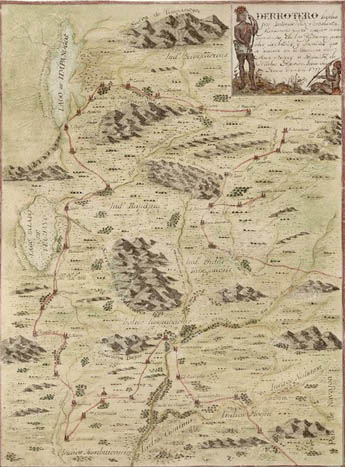

In that cartographic era—the centuries of European discovery—the hastily scrawled journals of voyagers were fleshed out by local stories, by legend and the imagination of the mapmaker. That’s why so many of them were comically wrong.

Long before the entire continent of America had been surveyed, European mapmakers relied on theory and imagination to make sense of all the reports sent home from shipboard observations. Explorations of the new world’s Atlantic side had little to inform the explorations from the Pacific side. And tense relations between the colonizing countries meant little knowledge was shared. So the mapmakers would rationalize the vast space in between the known and unknown with imagined water paths and inland seas.

The future Great Salt Lake was postulated, and described by native sources, for at least a century before it was surveyed by Europeans. So, on such vague information, it was called by different names, moved north and moved south, given numerous non-existent outlets, and greatly enlarged or shrunk, from map to map. Sometimes it wasn’t included at all, even after it had appeared elsewhere.

In other maps, the eastern half of Oregon sat below imagined waters. Some cartographers lengthened the St Lawrence River until it spanned the continent to reach the Gulf of California. California itself was frequently depicted throughout the 1600s as a long skinny island in the Pacific.

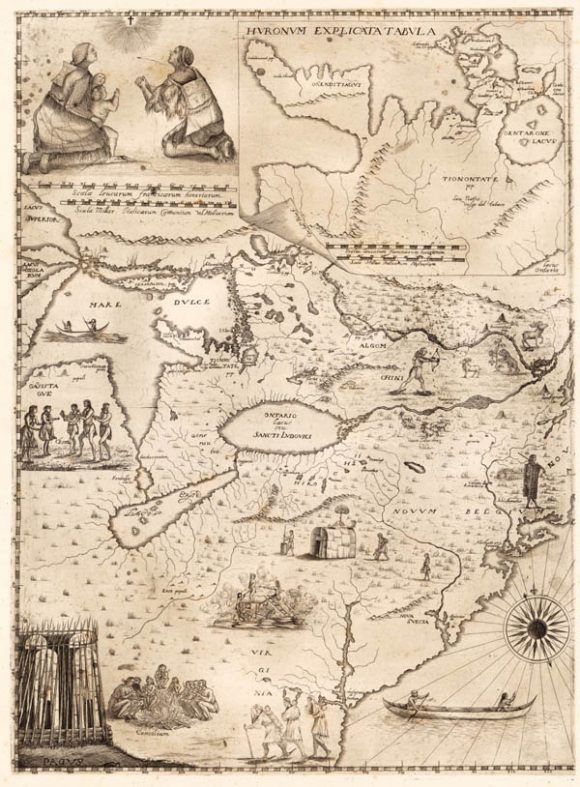

The best inland maps were produced by the French, who considered themselves the rightful owners of that vast wilderness long before they had ever surveyed it. Their maps often relied on the accounts of Jesuit missionaries, who had traveled farther along the inland rivers than anyone else. One of those missionaries, Father Francesco Guiseppe Bressani, drew a remarkably complex and generally accurate map in 1657 of all the American lands known to himself and his fellow Jesuits. He managed this feat despite having lost most of his fingers—the result of torture he received as a captive of the Iroquois. Maps, in his day, were the product of memory, and his memories were worth the pain and awkwardness of their transcription.

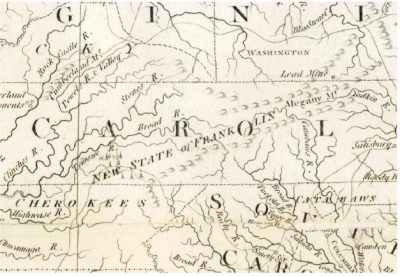

Those old maps still hold their memories, for better and for worse. They contain the fables and the strange ideas of their time, long after they’ve been abandoned. Proposals that never became projects; grids that were never laid on the ground. Short-lived notions and wild hares. For example: a few maps, drawn between 1784 and 1790, show a forgotten 14th State in our young disorganized country. The state of Franklin. Territories were still malleable and boundaries were vague in those days. Even our form of national government—at that point, a loose confederation—was yet to be finalized. So why not a state of Franklin? Formed out of western lands that had been ceded by North Carolina, the small mountainous region declared itself an independent state in 1784 and elected itself one Governor. But his term was the full life of the autonomous state of Franklin. Failing to win the required national support, the state was dissolved and re-absorbed into North Carolina in 1789.

But then, in 1796, North Carolina (apparently not very fond of those mountainous regions) ceded their western lands again. The old state of Franklin was absorbed into the brand-new state of Tennessee. And that new state elected its own first governor, a John Sevier, who curiously had also been the one elected Governor of Franklin. It tells you something of his influence. Just think of the world John Sevier lived in. A country in which boundaries constantly flexed and re-drew themselves; and yet somehow he remained at the crest of the time and that particular place. The state is long-since forgotten. But still, on a handful of maps, the boundaries of Franklin ring with as much authority as do Delaware’s or Pennsylvania’s. Those maps are only a curiosity now. Only a memory, preserved beyond usefulness.

Maps are forgotten by the larger public when they cease to describe reality. A map is born for use, and it dies when it loses its worth as a functional object. The question we are most likely to ask of a map, after all, is how do I get from this point to that point? And if the map answers poorly, we may be misled into danger. We may end up…well, in Texas perhaps instead of Louisiana, like the unfortunate French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. He had only himself to blame for his mishaps—his own poor cartography skills on his previous journey down the Mississippi. Trusting his own map from the subsequent trip, La Salle wandered far too West along the gulf coast to settle the future New Orleans, which was his intent. He died in 1687 during a mutiny of his own men near now-Navasota, Texas. They had grown tired of searching for the mouth of this supposed great river, which had been, in fact, far in their rear-view. You have to feel sorry for poor La Salle. He must have watched the unfamiliar coastline with increasing dread each day, murmuring again and again, “I could have sworn that river was somewhere around here…”

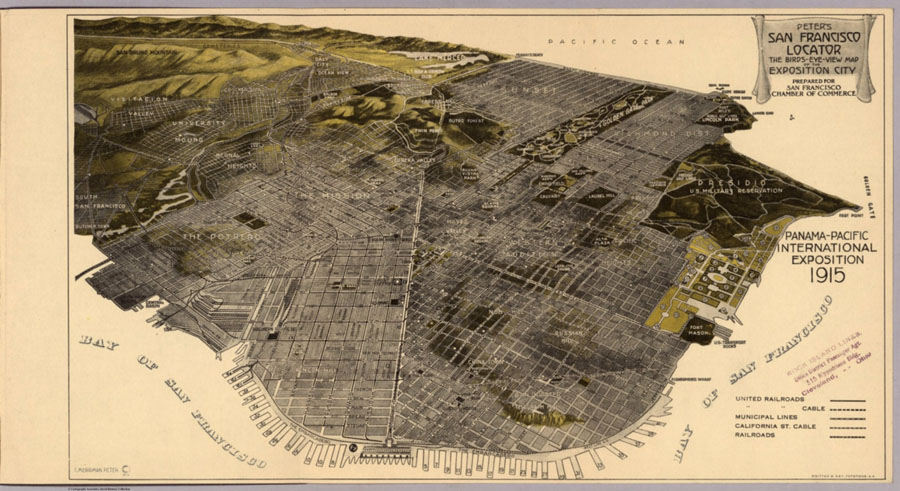

But some of us do enjoy maps even after they’ve outlived their original usefulness. We wouldn’t use them to reach Sarasota, but we love them all the same. We may even enjoy maps that were never particularly useful in the first place. For their beauty, if nothing else. A pre-computerized map was an idiosyncratic creature, with individual (if distinct and easy-to-read) handwritten place names. Hand-drawn mountains and rivers. Those mapmakers, hewing precisely as humanly possible to the known and surveyed characteristics of a place, betrayed themselves with an individualistic charm. Their maps were, after all, humanly possible. And they tell a human story—of individual human-known places as they were altered through the generations.

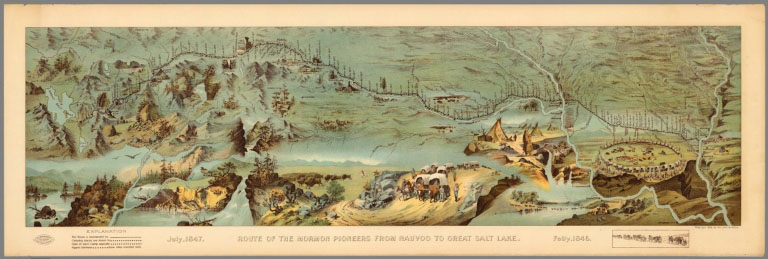

To trace a particular place on the earth through its lineage of maps is to experience time. Our own ancestors’ journeys over the landscape. Our plans and desires. Maps are a record of the human touch on the earth. We drew maps in order to recount our explorations, so they could be repeated and expanded. We drew maps to propose a field of battle, or a system of levies, or the grid that would maybe, or maybe not, become a city. Humans did not, by and large, want to draw maps of places where they didn’t intend to do something. And it might be unfashionable to respect that instinct in this particular era, but you have to at least acknowledge it as something innate to us. Humans know how memory can transcend death, and so we want to be a part of the cultural memory. To leave your imprint on the maps is to leave a mark in time.

Myself, I love maps because I love the peculiarities of human history. I’ll confess to a lack of interest in terrain for its own sake. A hill, yes, is a lovely thing. I can admire it. But I’ll take a second look once I see the ruins of some half-demolished home at its foot. Or the rusted remains of a cowboy camp. In the span of human memory, that hill is only a hill. On the scale of geologic time, I know it might have been a glacier. And some people have that Michener-esque imagination. But it’s beyond me.

The progression along that hill, however, of a footpath that becomes a wagon trail, which becomes a road, which becomes a habitable settlement….that is a movement across time that grabs my imagination. When a dusty street sprouts a row of buildings–among them an inn, which, after two hundred more years of history, is still remembered as the inn where some particular outlaw was shot by a dastardly cattle rustler…Now you’re traveling the terrain of human memory. The Mafia erecting itself a glittering oasis in the desert. Mulholland pouring the Owens Valley water into Los Angeles swimming pools. Rail lines stitching feverishly across the Plains. Telegraph lines, Greyhound bus lines, and the rise and fall of Midwestern Air fields. That kind of human terrain begets maps and more maps. It’s a landscape that creates and re-creates itself in endless cycles. The birth and death of bridges, of highways and factories, of entire cities. To look back at the map of human habitation and exploration, even from a distance of a single generation, is to draw excitement out of ashes. It rekindles the dreams of the dead.

To look at an old map is, at its heart, an act of desire. A desire to have been born with time and, like time, to keep ticking as lesser and greater civilizations are built, or destroyed. The map-lover’s desire can’t be fulfilled. It only frustrates. The scale is never as detailed as you would like. Your questions aren’t answered. Streets, and towns, and rail lines, disappear. Memories have been lost by generations of forgetfulness.

If you could, you would prefer to take up a long-lost moment in your hand. You would bring it to your mouth for a taste. You would walk down those streets, in that time, and hear how they sounded. You would cheer on the great bridges—the Brooklyn, the Golden Gate—as they were built. Watch as Kansas City’s waterfront was cut out of the rocky palisades. You would have stood with the crowd at Promontory Summit in 1869. But you will never have that chance.

Your foot is stubborn. It has been planted on the ground in this place and this time. Around you, everything spins. Streets. Buildings. Nations. They never settle. You look at the old maps because you’d like, just once, to lift your foot and step into the whirlwind with them. To travel the trails that will be roads, and take ferries across the harbors that will be bridged. You wish you could spin through time and fall to the earth somewhere, like Dorothy fell from the tornado, beyond the oceans surrounding your own Babylon.

But all you have are these tools. This magnifying glass. This particular archive to explore. You have the maps that have survived—ink set to paper—and just a little time. That’s all.

Tonya Audyn Stiles is Publisher and Managing Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

As I young child I was drawn to maps like comic books of the era. I use them in archival research from the colonial era in the U.S. Southwest and South America, and it is so true that a picture is worth a thousand words. Some years ago, I was contacted by a former Peace Corps Volunteer who was collecting hand drawn maps from those of us who were former Peace Corps Volunteers. His compilation of maps resulted in a beautiful publication entitled “Maps and Mapmakers of the Peace Corps” with contributions from PCVs who have served from the 1960s to the present throughout the world. Last I checked it was available on-line.

I am a 20th century analog old guy living in a 21st century digital world and I still use paper maps when I travel because maps give alternatives and let me know what those alternatives are. One’s smartypants phone can tell you where you are and get you to where you want to go, mostly but not always. Thanks, Siri.

But I love looking at a map to see where I am and then seeing the other roads and how they might get me to my destination in other ways and what might be on those alternate roads. I usually find those roads less traveled to be the travel equivalent of the slow food movement i.e. much better for nourishing body, mind, and soul.

I’ve always regarded maps as a form of literature. I love looking at old maps and imagining what travel must have been like, especially around Moab, when everything was dirt or gravel. Planning summer trips poring over maps and imagining where we might go used up many pleasurable hours. I apparently picked up this habit from my mother, who used to do the same thing before any trip.

Maps, gotta love the old guys. My latest obsession is finding those spots that aren’t on the map. Every map has its boundaries and of course there is something beyond…when I peruse the latest recreation trail map issued, on the shelf at our local mountain sports store, I’m overjoyed when I realize the crowd will not know what lays beyond the edge of the map. In that sense, I am now more interested in what the maps leave out than what they include. Of course! I now have a collection of old maps that I could never throw away.

Maps have influenced my life perhaps as much as books. My affliction led to a course in Cartography.

A map caused me to fail Calculus. In ’74 I had a big wall map of Alaska taped to the cinder block wall over my desk in the dorm room. So much easier to daydream of those far away wild, roadless places than figure out what to do with that squiggly infinity symbol.

Years after scouring road maps and finding the largest roadless area in the lower 48, serendipitously I happened to spend more than 10 years living in and exploring the Salmon River country of Idaho.

The large topo of Canyonlands with little x’s and squares penciled in where evidence of the Long Ago People could be found and little dashes penciled in showing routes between canyons, which ones required a rope and where I might find water. That map near ’bout wore out before I salvaged some of the personal data.

If I could only have one app on my computer it would probably be Google Earth.

I felt like an old out of touch Luddite ‘rent when I saw the facility with which my kids picked up Google Maps.

That was before I found out they didn’t have an idea in hell about how to read a real one. Google Maps, I might have found out before them, doesn’t always tell you where you’re going or where you are. You need a real map for that.

Nicely done, Tonya. Yep, it certainly is nice to know what a magnifying glass is for.

It is indeed fun to think of how our knowledge of the landscape has changed and how maps have struggled to keep current. Even Google Earth becomes dated when you look closely and know from experience what changes have taken place in your own little area that Google Earth has not yet shown. Since Tonya, in her very interesting article, wrote about Utah let me add Patsy’s memory of the road from Blanding to Bluff, Utah which was a trip of 26 miles. The outdoor swimming pond in Bluff was unlike anything in Blanding and a big attraction to young people in Blanding. In the 1940s Patsy and a girl friend rode their bikes to Bluff to go swimming and then caught the mail truck for the return trip. The first time they went the road was natural dirt with a lot of sand which resulted in having to push their bikes part of the way. The second trip was on a gravel road. The third trip was on an asphalt road and relatively smooth going. She admits that her memory might not match other information about the road to Bluff.

Fresh out of college in ’56, immediately becoming a “ward” of the USGS Topo Division, spent most of a decade doing what Major Powell had done—a little further west and a century earlier—hoofing it, with K & E alidade in hand, and a plain table over my shoulder—sketching quadrangles BY HAND, IN THE FIELD—from Avery Island, Louisiana to Minnesota cranberry bogs.

How could I help it—REAL MAPS became my passion, a turn of mind that technology will never touch! During those nomadic days, landladies sometimes admitted (in words approximating)— “I had to show your room to so-and-so today, all those maps you put up make such interesting wallpaper.”

From the perspective of those NOT THUS ADDICTED, they have no idea how such a combination of lines and symbols speak to one of the MOST tangible, single aspect of our earthly tenure—landscape, and its still, indescribable variation. (Pardon me Tonya, but those roads and the places they connect are mere ephemera—tolerated by cartographers only to the extent that their inclusion creates a market—for ephemera.

“CLINGING TO THE PAST” is not only a catchy slogan—coined by certain journalistic types—it remains an enduring WAY OF LIFE, so long as humanity endures and tangible provides it place to stand.

Loved the early maps, especially of Colorado R. and Glen Canyon which I traversed in 1962 with UC Berkeley students TWICE when Page Dam closed, and “Greatest Story Ever Told” was being filmed there…quite a story. Let me know if Zephyr interested in my telling of it…

can’t add anything after all the XXXcellent comments previously. and, gosh-darn, i ain’t never knew nor heard about the state of Franklin, ’til this essay. quite scholarly, interestingly anecdotal, Tonya !

Thank you Tonya Audyn Styles for your lovely tour to the place called maps. This morning, for a while, I was as lost in your writing as I often become when staring at a map, any map, with the road ahead.

My map story today: recently, clearing through my mother’s possessions, I came across a 1960’s lunch pail and found inside, fifty maps from fifty states, the studious project of yours truly, preteen, 1966, where I had written every travel bureau in the 50 states and asked for a travel map. This was a time way, way before the one-click world we currently occupy. Yet there they were, carefully archived, in alphabetical order.

Thank you mother, Joan Whitaker Maurer Viktorin Beale, for the tangible memory of a forgotten self.

Canyon Country Zephyr, you are the Utne Reader of the beauty and place and history of eastern Utah.

Richard Viktorin

Austin, Texas

p.s., if you are ever in Austin, Texas, please visit the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas at Austin where there are bountiful big and wide and deep map cases. Online for sure, but there is no substitute for putting on white gloves and pulling an historical map up on the the top of the display cabinet for a real touchy-feely, hands on look, at a masterpiece of cartography. Or a road map of Utah, 1966.

Maps and cookbooks. I may not go there or cook that, but I know where it is and what I need to cook it.

This old surveyor/mapmaker/topography nerd thoroughly enjoyed this very interesting essay. Thanks, Tonya!

Maps are really cool. I always see vintage ones when antiquing, I really need to pick some up.

This is a gorgeous piece, Tonya, but I suspect that there are far more map lovers than you might have guessed. Especially among the readers of the Zephyr. Thank you.

Great article, thanks.

I just love maps. That may be part of the reason why I became a geographer (amongst other things). And it’s paper maps that I use – boxes of them at home. Never throw one away unless it’s so torn up at the folds and irreparable.

I travel a lot , in the western US (and in Australia, New Zealand and the mountains of Latin America). In the US i have a car and get into all sorts of interesting and remote places. When I tell people about some of the places they ask how I find my way around, and then say, oh, well you have a G.P.S. And I reply, no, I have a G.P.S precursor, it’s called M.A.P!! Eventually they get it. (Sometimes I say I have an M app.)

Remember when gas stations had an office — not a mini-mart — with maybe a few candy bars for sale and a Coke machine that was a glorified refrigerator with a coin slot and a dispenser! And they had a wire rack with FREE quality maps of not only the state you were in, but usually neighboring states.

I hope it doesn’t distress you that I seem to always have a comment! But maps and history are so attached as shown by the really old ones you pictured. Certainly not as old but for 20 years of our retirement we volunteered at Goff, CA for the Mojave Desert heritage and Cultural Assoc. and there everyone revered maps! We have quite a huge collection there. At another time my late husband and I hiked in Copper Canyon, Mexico where we found two old, not dated, maps in Spanish. We were allowed to photograph them and I added them to a book I wrote about Nelson, NV. As a child in Searchlight, NV the road ro las Vegas , now U. S. 95, was not paved. It wandered across the then pretty large Dry Lake. Sometimes someone rode on the hood to watch for bug dust holes which we’d avoid Then we could choose a less pot holed road, certainly not laid out, just wherever it looked smoothest!