The most inaccessible, least known, and roughest portion of the Navajo Reservation is bounded by the Navajo, Colorado, San Juan, and Piute canyons. […] Buttes, mesas, and small domes predominate and are so tightly packed that the base of one flattened dome of erosion butts against that of its neighbor. The deep canyon trenches are practically impassable and the buttresses flanking the cathedral spires are so narrow, smooth, and rounded that passage from one to another and access to the capping mesas have so far not been attained. […T]he experience of my party indicates that exploration in this canyoned land may be accompanied by hardships.

—Geologist Herbert E. Gregory

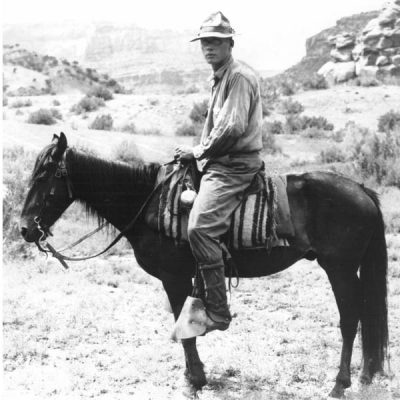

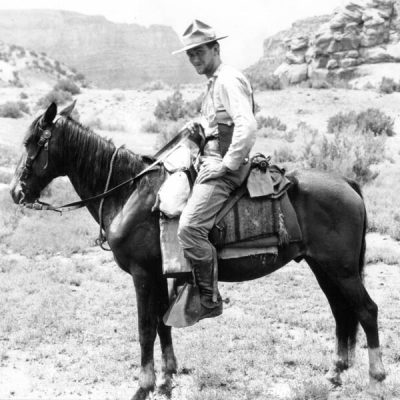

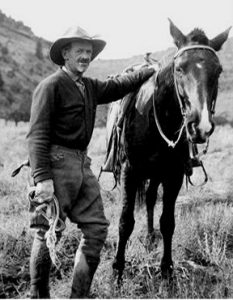

In my August/September 2017 Canyon Country Zephyr article entitled “The Strenuous Life,” I recounted a challenging voyage taken by my elderly great-grandfather, John Wetherill, and a young companion, who boated into Glen Canyon on the Colorado River in January of 1931. The men faced many difficulties such as bitterly cold wind, dunkings in the icy water, and loss of all of their food, but Wetherill remained upbeat about the voyage. “The hardships we went through only add value to a wonderful experience,” he asserted.

John’s optimistic outlook and disregard of adversity was the outcome of his decades of ramblings around the rugged Four Corners country. His positive attitude and fortitude also reflected his affinity with his Native American friends who considered these positive attributes to be a natural and proper part of life.

The wild country is a land of dangers, both real and perceived. Since few resupply options exist, food must be brought in, obtained from the land, or bartered from others. Life-giving water is scarce, and the explorer must know how and where to find it. Steep and rocky routes through all sorts of broken-up country, such as canyons, domes, ridges, and slopes, must be traversed with great care in order to avoid injury or worse. Where precipitous canyon walls and ledges block progress, alternate routes must be found, sometimes requiring skillful pathfinding and long detours. And there are many annoyances, such as heat, cold, wind, blowing sand, stinging and biting insects, hard ground to sleep on, aching muscles, exhaustion, and misbehaving livestock.

For Wetherill and his Native American neighbors, the intense beauty and wholesome effects of time spent in the outdoors made the associated troubles, which “civilized” folks would think of as miserable and dangerous, seem trivial or even edifying. Furthermore, the explorers’ adventures gave them great advantage by hardening them against some of the common maladies of those who stay at home—complacency, despondency, banality, preoccupation with trivialities, and premature physical and mental enfeeblement.

Like his native friends, Wetherill had learned how to avoid situations that were truly dangerous as well as how to dispel his unreasonable fears of conditions that at first seemed serious, but were really benign. In his role as a backcountry guide, he had many opportunities to exemplify these skills and attitudes to his clients. Some of them were better learners than others.

An example of a backcountry trek that involved many hardships and learning opportunities was the 1909 Utah Archaeological Expedition, which was led by professor Byron Cummings of the University of Utah. Most of the participants left written accounts of their experiences, and two of them took photographs.

In 1979, I was most fortunate to meet Stan Jones, aka “Mr. Lake Powell.” He had researched this trip in great depth in preparation for a book on the subject, which he published in 2004 as Into Unknown Canyons. Stan introduced me to the canyon country where I followed, for the first time, some of my great-grandfather’s trails. Stan graciously gifted me with his voluminous research materials before his passing in 2007.

During my early treks, I found myself wishing for a soft bed and craving certain foods that were not on our menu. Over time, though, those yearnings diminished until I found myself sleeping better on the ground than at home, and I came to savor our simple camp fare. I had a few mishaps, too, such as the time an obstreperous horse dumped me on the ground, resulting in a gash in my scalp. Those were learning experiences.

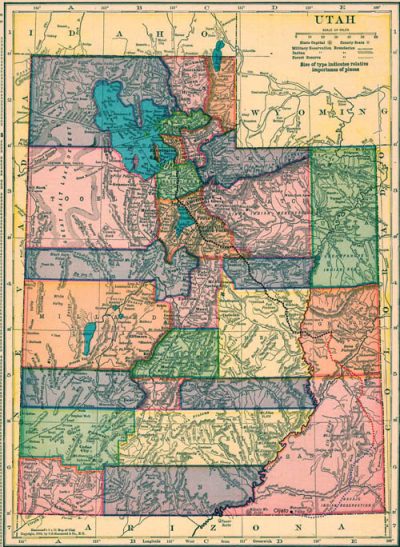

Byron Cummings, age 48, was professor of classical languages and Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Utah. He expanded his curriculum to include Southwestern archaeology and had already, in 1907 and 1908, taken students on summer excursions into culture-rich areas of southeastern Utah. The 1909 trip was sponsored by the University of Utah and the Utah Society of the Archaeological Institute of America, of which Cummings was president. The Utah legislature appropriated $1000 for expenses associated with research within the state, and Colonel Wall of Salt Lake City added $600 for the Arizona portion of the work. Cummings would conduct his archaeological investigations, excavations, and collection of artifacts from public land for the university museum under a federal government permit. The permit was in the name of Edgar Lee Hewett, director of the School of American Archaeology at Santa Fe and one of the authors of the 1906 Antiquities Act.

Accompanying Cummings was his 21-year-old nephew, Neil Judd, who was studying arts at the University; 18-year-old Stuart Young, a student of mining engineering and grandson of the Mormon leader Brigham Young; 24-year-old Donald Beauregard, a talented artist who had studied at Brigham Young University and the University of Utah; Cummings’s 11-year-old son, Malcolm; and Dr. William Blum, age 27, professor of chemistry at the university. Judd was a seasoned explorer, having traveled with his uncle on the 1907 and 1908 expeditions.

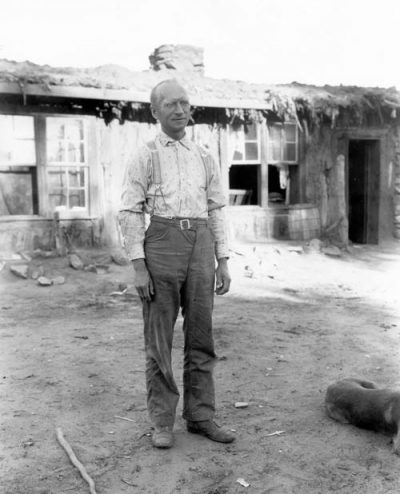

Cummings had arranged with veteran explorer John Wetherill to provide logistical support for the trip, including outfitting and guide services. Wetherill lived with his wife, Louisa; children, Ben and Georgia Ida; and trading partner, Clyde Colville, at his remote outpost of Oljato (Ooljéé’tó: Moonlight Water), Utah, just west of Monument Valley (see my article, “A Home on the Desert: Establishment of the Wetherill & Colville Trading Post at Oljato, Utah in 1906” in the October/November 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr). The region was the traditional home of Navajos and Paiutes, and the Wetherill and Colville Trading Post provided supplies hauled in from distant towns in exchange for wool, skins, and other trade goods. It would serve as the expedition’s jumping off place for their archaeological studies.

The adventurers boarded the train in Salt Lake City on June 7 and disembarked at 4:30 the next morning at Thompson’s, about 200 miles down the line. Don Beauregard described the stop as “a typical frontier town consisting of two water tanks, a mountain, and a station.” The train rolled out with Stuart’s pocketbook still on board, so arrangements were made to bring it back to Thompson’s, then send it on from there to Moab with the rest of the luggage.

“All against our will,” Don recorded, “Prof. Cummings gathered us around him under the water tanks and quietly preached us a little sermon on cow boy etiquette. This last would have been entirely uncalled for had not Dr. Blum insisted on brandishing a lasso just as a westbound train shot past the station.”

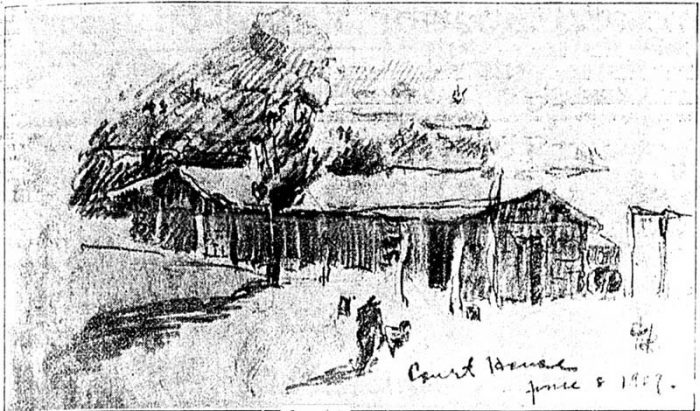

At seven that morning, the men boarded a stage that was headed to Moab, about 40 miles to the south. At noon they reached Court House Station where they ate lunch. According to Don, the establishment was the namesake of “a lonely butte resting like a huge court house in the center of the wilds, dramatically proud of its ornate exterior.”

The topography was new and interesting to Don and Stuart (and probably Malcolm, too), and so was their first view of a cliff dwelling three miles before they reached the Colorado River. “On seeing such a sight for the first time, the dream of primitive men is made a thousand times more real than words can tell,” Don remarked. The river was running high, but they crossed it safely—some of them on the ferry and others in a rowboat. From there they rode on in to Moab “with a layer of dust on the outside and a lining of dust on the inside.”

“Moab we find surprisingly cheerful and green, especially after a hot ride through the sand,” Don recorded in one of his reports, which he sent to Salt Lake City for publication in the Deseret Evening News. “In fact it is a sort of oasis with fields of flowing alfalfa and orchards of splendid fruit. The mowers are busy, cherries are hanging ripe from the trees, and the gardens are full of vegetables. You must know this to understand that Moab is a thrifty little town (with a thousand healthy souls) studded like an emerald in the heart of the desert and 4,000 feet high.” There they bought three horses.

The group waited two days for their baggage to arrive from Thompson’s, then they prepared to head south. They hired a Mr. Redd to haul the gear in a wagon drawn by four horses, and Prof., Malcolm, and Don rode their three new horses. Beginning late in the day, they made it only ten miles to Sommerville’s ranch, where they camped.

At about four the next afternoon, the travelers reached Hatch Wash. Memories of the place were vivid in Neil’s mind. “It was at Hatch Wash in 1907 that I learned, once and for all, never to spread my bedroll in a roadway,” he recalled. “The sun had gone down that night in traditional splendor—a gorgeous display of reds and pinks and purples; the stars had burst from a cloudless sky and were almost within reach. But sometime after our party retired a storm passed overhead, and before I could get out of the way a muddy rivulet came racing down the wheel track right through my bed tarp and blankets. The spot had seemed such a clever selection, with our wagon blocking all traffic and the wheel rut just deep enough to hold my canvas-covered bed.”

The next morning, the expeditioners continued on into Monticello. There, Cummings bought two more horses, as well as four burros to carry the gear. The Redd family provided the group with meals and a place to camp. “We are now 100 miles from the railroad at the county seat of San Juan,” Don reported. “It is pitched on the eastern slope of the Blue mountains 7,000 feet high and commands an extensive view of solitary desert far into Colorado. There are about 300 souls in the village living in respectful tranquility on their farms. They possess about 3,000 head of cattle which means a comfortable existence for the town, and we are informed that about 50,000 acres of arid land have been reclaimed since last July for dry farming purposes.”

“We are now on the edge of the great wilds and expect soon to enter the extremities,” Don added.

After a Sunday rest day, the party proceeded south on their own. They had considerable trouble with the burros but, despite delays, reached the newly-established town of Grayson (later named Blanding) that evening.

On Tuesday, June 15, they traveled from Grayson to Bluff. Hewett’s arrival in Bluff coincided with theirs. He would be with them for the first ten days in his role as the official permit holder under the Antiquities Act. The next day, John Wetherill also came into town accompanied by a Navajo wrangler named Dogeye Begay (Dághá Biye′: Son of Mustache). Wetherill would guide the entourage on to Oljato.

The adventurers then began reckoning with their first major hardship. Although modern motorists can travel from Bluff to Oljato in about an hour along paved roads and the bridge across the San Juan River at Mexican Hat, the route in 1909 involved a three-day horseback ride over faint and rocky trails, beginning with the challenge of fording the river. That challenge was particularly formidable and frightening in 1909 because the river was in flood stage as a result of heavy runoff from the spring rains. The leaders chose not to use the conventional hard-bottom ford near Comb Wash several miles downstream, probably because it was unsafe due to the high water, but instead to attempt the crossing about a mile above town.

Cummings dickered with two young Navajo men—one of them named Randolph—to help them with their watery task. Wetherill served as the interpreter. At first, Randolph and his partner were reluctant to get involved, but, with some urging, they finally agreed to do the job for a fee of $15. They took the saddles across in a skiff and drove some of the horses and burros into the water. The burros made it to the opposite bank with no trouble, but some of the horses turned back. One of the young men tried again, this time riding a horse and leading and driving others. His companion followed behind on his horse. Most of the animals made it through, but, again, two of them turned back. The first man then swam back and was able to coax the rest of the horses to cross. The expedition members decided to delay their own crossings until the next day.

In the morning, the Navajo men took the camping gear across in the boat, then they began to ferry the team members, four at a time. Stuart was among the last, and he recorded their struggles in his journal. After crossing a deep channel, the boat became grounded on a sandbar, and the boaters had to get in the river to maneuver it around. They ended up in water up to their waists and then encountered patches of quicksand. “It was quite hard going,” Stuart wrote. “Several began going down, but not even a piece of baggage was wet, so we had pretty good luck. We then landed on an island and had a portage of about a half mile, and then we again took to the water. The bottom of the river was filled with small loose rocks, which made traveling hard. After landing on the other bank I took the picture of the bunch as they were when crossing.”

Don attributed the group’s success to the skill of their two young helpers. “We contracted the crossing to two Navajo Indian boys,” he wrote, “and had it not been for an extreme coolness on their part and on their absolute knowledge of every nook in the river we should either have been washed down by the swift current or sunk into the quicksands that lie so treacherously along the bottom of the river. It was a sight to make one’s heart stop beating when the two boys with the horses got far out in the river fighting for a projecting sandbar, and to gain it only to drop down suddenly in a bed of quicksand and then fight with every fiber to pull themselves out. Time and time again this happened before the opposite bank was reached. Several times our men fought as desperately to retain their footing against the current of the stream and two of them sank dangerously low in the sand. Those only who have witnessed the perils of frontier life can imagine how joyous we all were when the last man pulled himself on to the dry bank.”

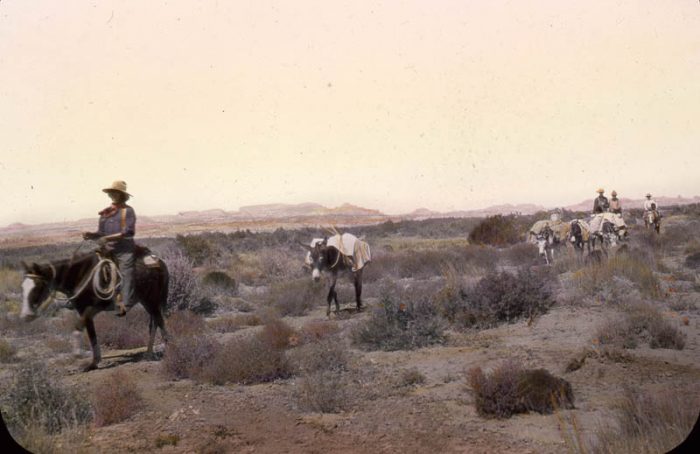

Once they were safely ashore, they packed their belongings and ascended an Indian trail to the top of the bluff. From there they headed southwest. “We traveled through a typical desert,” Stuart wrote in his diary. “Red sand was everywhere, piled up in dunes or drifting along on the level. To the right were great mesas, one which we noted particularly, being at least 25 miles long and perfectly flat on top. That night we camped on a large flat rock, overlooking the Chin Lee river. A little spring came out from between the rocks and furnished us with the best water we had had so far.”

Stuart then described the beginning of the next morning’s trek down into Chinle Wash. They followed a route that “was mostly rough on the horses, being over solid rock and on the sides of cliffs, some of which were quite high.” After more ups and downs, they ascended a mesa where they stopped for the night. They were nearing Monument Valley (at the time called Monumental Park) and were enthralled by the views.

The next day, by the time they reached the monuments, the wind had picked up and was blowing sand into their faces. Nevertheless, Don declared the area as “the most wonderful and least known of any spot in the world.” “It is so completely surrounded by vast tracts of desert that the ordinary tourist would find it disagreeable to make the tour, but for one who is not afraid of the hot winds and hot sand and a hot sun, Monumental Park would present new wonders unequaled elsewhere,” he wrote. “As our caravan passed under one of the lone sentinels, every man stopped quite unconsciously and gazed upward as a child would gaze at the sun, awe struck by the handiwork of omnipotent powers.”

“It is a sight without parallel, and some day tourists will pour in there by millions,” Don predicted.

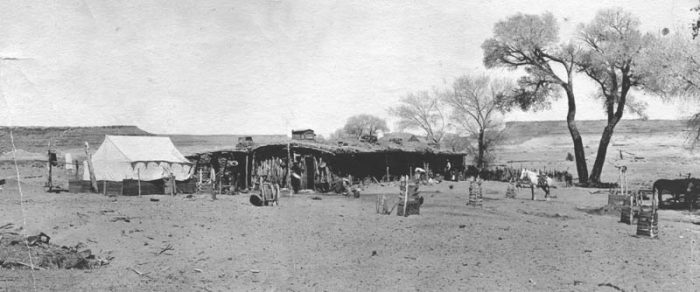

At 5 P.M., the team reached Oljato. Don described the scene:

Oljato, which consists of a cottonwood tree, a spring of water and lone house, lies directly to the southwest just three-quarters of a mile north of the Arizona line and is possibly one of the finest examples of existing frontier trading posts. Mail reaches the place but once a week, and that is carried on horseback by a Navajo Indian medicine man. Supplies are brought in by way of Gallup in Arizona [sic] by ox teams, taking about 21 days to make the trip. The hills about are crowded with goat herds owned by Navajos, and it affords a most picturesque sight to see them shooting down over a barren stone ridge or through yellow sands followed by an Indian boy or girl with their bows and arrows, most probably more interested in finding a lizard or a snake than in the welfare of the goats. The romantic hogans are pitched promiscuously in old corners and the Indians wander around quite contented with their allotment in life.

Professor Cummings and Neil Judd, having visited Oljato the year before, were in familiar territory. The others must have been quite intrigued by the little spot of civilization in the midst of a great wilderness. Cummings had great respect for his hosts. “Here one family of white people live in the midst of the Navajo nation, 150 miles from the nearest railroad point. Nevertheless, they are people of education and culture, speak the Navajo language fluently, are much interested in the welfare of the Indians and are doing an excellent work among them,” he wrote. “Mrs. John Wetherill is undoubtedly the best Navajo scholar living. She has the confidence of the Indians and will be able to do a great service to the scientific world in gathering data which will give a knowledge of this people.” (For more on Louisa, see my article, “Slim Woman of Kayenta” in the February/March 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr)

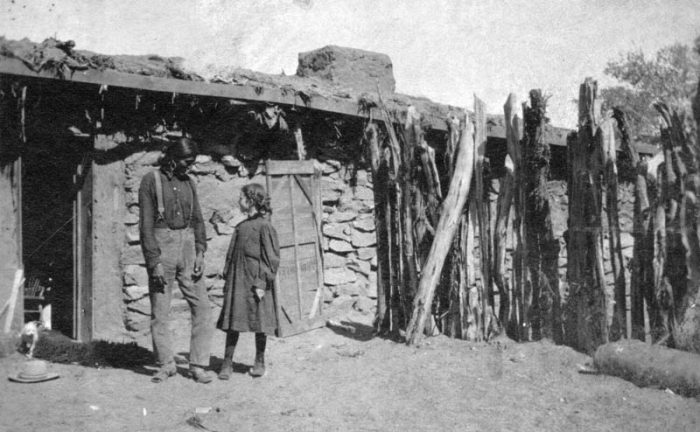

The presence of Louisa Wetherill and daughter Georgia Ida added a feminine dimension to what had theretofore primarily been a masculine-dominated journey. Don, in particular, was intrigued by the presence of a spirited young Anglo girl living in such a remote place:

The most interesting feature of our visit here is the acquaintance of little Miss Ida Weatherell [sic], 11 years old, who has charmed our party with her vivacity and various talents. It is particularly instructive to hear her talk with the Navajos quite as unconcerned as she talks English, and to see how she is able to handle them to her liking. One might think to hear her talk that she is a matured young lady. She has gained the sense of responsibility that isolation only can give and at the same time she has kept her childish charms.

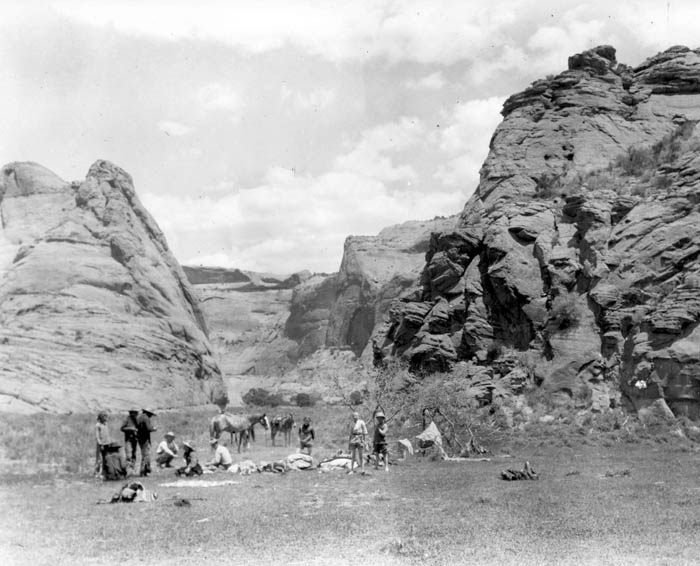

A few days later, the explorers headed out for a canyon called Segihotsosi (Tséyi’ Hats’ózí: Slender Canyon) south of Oljato. There they established a camp and proceeded with their archaeological investigations.

Camping was primitive by today’s standards. Meals were prepared over coals in a dutch oven, often by Professor Cummings, who was a veteran of desert cooking. “Boiled rice, reddened by sediment in surface water left by the last rains, and baking powder biscuits hot from the Dutch oven!” Neil wrote. “I grieve for any man who escapes these mortal coils without having tasted a Dutch-oven biscuit. What matter if the bread be dun-colored, brick-hued from such scanty water as the desert provides? I’ve known biscuits so red that experience dictated the wisdom of marking their position, when set out to cool on the red sandstone that answered as table. But such soul-satisfying biscuits, such melt-in-your-mouth biscuits are only produced in a Dutch oven, aged by the pungent smoke of countless sage and cedar fires.”

Tents, mattresses, and pillows were not used. Bedding consisted of a simple bedroll—a large tarp and some blankets or a quilt. Protection from blowing sand or rain in the night could be accomplished by pulling the tarp over oneself. “After a long hot day across sandy valleys and tablelands, with dust devils whirling and dancing to right and left, sleep comes early and easily,” Neil recorded. “Then tired muscles relax to fit any irregularities of the ground and even a sandstone mattress vies in comfort with the best offered by Fred Harvey’s justly famed hotels.”

On the trail, thirst and dehydration were concerns, both for the men and the animals. Neil told of a time when they were climbing out of a canyon and ran out of water: “Canteens were empty when we reached the top; mouths dry; tongues thick and cottoned. It had been beastly hot on the long, upward grade with a merciless sun beating full upon us. But a mile or more back from the rim, shallow pools of recent rain water marked the summit; into those pools went fevered noses, horses and men side by side. Did you ever stretch out your belly beside a sun-warmed puddle, frighten away clustering little black wrigglers with a finger wagging at your lips and strain in through clenched teeth long draughts to sooth a parched gullet?”

For the next six weeks, the team explored, excavated, and studied the buildings and artifacts of the ancient inhabitants of the region. Some members of the party visited the cliff dwellings now known as Keet Seel and Inscription House, and they were the first outsiders of record to visit the beautiful dwelling of Betatakin, based on intelligence and guidance from some Navajo folks who lived near there.

In August, the explorers set out (in the absence of Dr. Blum, who had returned to Salt Lake City early) on a long journey to look for a rumored natural bridge far to the west near Navajo Mountain. In that quest, they endured many more hardships and experienced many more wonderful experiences, culminating in gazing upon the treasure at the end of the trail— the magnificent Rainbow Natural Bridge. But, to quote my great-grandfather, John Wetherill, “As Kipling would say, this is another story.”

The hardships that the explorers faced during their summer adventure were not mere distractions from the pleasurable experiences, but had the invaluable benefit of making them more wise, perceptive, patient, resilient, and tough. The troubles gave them greater courage and insight to face life’s ongoing challenges and the will-power to pursue other rewarding quests that less-adventurous folks would shy away from.

When the hardships were unnecessary and self-imposed, such as Neil’s unexpected nighttime drenching in his poorly-chosen bed site, the mishaps became instructive, both for the victim and others who he could wisely advise. When the hardships were unavoidable, such as those that resulted from the innate character of the countryside or the vagaries of weather, the expeditioners learned to harden themselves and, when necessary, seek input from more experienced people who could help them navigate the trails and trials. In so doing, they succeeded both in avoiding situations that would have been dire and alleviating their unfounded fears of those that were not. As those fears subsided, their eyes increasingly opened to the marvels surrounding them.

Like John Wetherill on his Colorado River adventure years later, the team members experienced many hardships that ultimately added value to their “wonderful experience.” Perhaps it was Neil Judd who best summed up their success. “Looking back over my shoulder, I am sure no future experience can equal the rewards of those early days along the San Juan, in southeastern Utah and northeastern Arizona,” he reminisced.

.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer. Click here for more articles by Harvey Leake.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

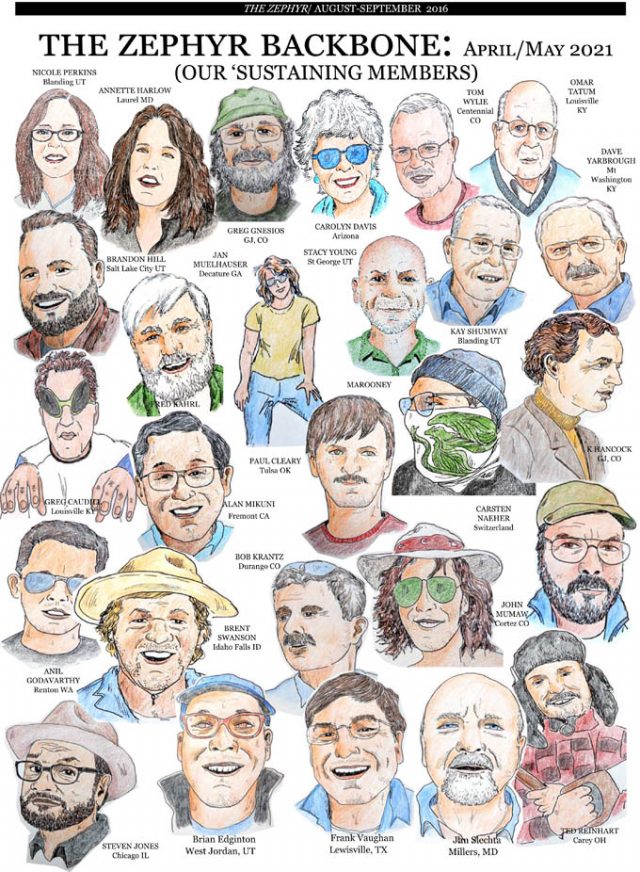

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Fascinating historical tale of an adventure journey through unspoiled regions of the west. Interesting and inspiring.

Oh dear: “Moab we find surprisingly cheerful and green, especially after a hot ride through the sand,” Don recorded in one of his reports, which he sent to Salt Lake City for publication in the Deseret Evening News. “In fact it is a sort of oasis with fields of flowing alfalfa and orchards of splendid fruit. The mowers are busy, cherries are hanging ripe from the trees, and the gardens are full of vegetables. You must know this to understand that Moab is a thrifty little town (with a thousand healthy souls) studded like an emerald in the heart of the desert and 4,000 feet high.”

And now? “Moab we find surprisingly crowded and chic,… it is a sort of West Hollywood with cutely named reasaurants where you can get a cup ‘o’ joe for eight bucks: shops crammed with trinkets and obscenely priced “outdoor” gear; hordes of no body-fat mountain bike Nazis, bloated mansions and a few remaining locals who look as if they are in shock. Moab is a devastated little town oozing like an infected wound on Instagram, Facebook and other social media Transyvanias.

“Common maladys of those who stay at home.”

Now I know what is wrong with me. I wish I had known this when I was younger.

I know maladys is not the correct spelling. Spell check won’t let me spell it correctly.