Note: This article first appeared in the October/November 2011 Zephyr…

Many years ago, during one of my first trips to the canyon country, I made the dusty drive to Grandview Point on the Island in the Sky. The road was still dirt and gravel then; hardly anybody made the trip. On Labor Day weekend I had the campground to myself.

From my vantage point, I could see much of the land that would be my home for the next 30 years. Some of those distant landmarks would become familiar to me. It’s a unique experience to stare at a hazy mountain peak, 75 miles away, and know exactly what it looks like to be on its summit staring back. Other places I’ve left alone, either because they’ve since become too crowded for me to tolerate, or else I never got around to getting there.

Knowing there are still unseen ‘gettin’ places’ to go to is comforting. Knowing they exist and that I don’t need to go to each of them to appreciate their beauty is comforting as well.

Some of those “gettin’ places” are more pristine than others. On that first visit to the Island, I recall seeing the long bands of denuded patches of vegetation on the White Rim, 2000 feet below. They looked like Anasazi air strips and they were, though not quite that old. All over canyon country, landing strips from the uranium days were and are still clearly visible. Later when I became a ranger, I learned that the disturbed landscape was blackbrush, that this particular high desert plant did not do well when messed with, and that scars such as the ones visible on the White Rim might be there for decades.

This infuriated me, of course. As a ranger I participated in several blackbrush studies and assisted in token efforts by the Park Service to re-plant some damaged plant communities at Arches National Park. Years passed. The scars are still there. There’s some improvement after 30 years, but not much. Some day, the scars will be gone, I’m sure of it, but not in my lifetime.

I used to go ballistic over seismic lines. Still do. These damn trucks would rumble across the desert in Little Valley, just inches from the park boundary with their thumper trucks and geophones. You can still see those scars too. ATVers and bicyclists use them nowadays, exacerbating an already bad situation. Ugly.

Among my diverse group of friends, my pal Lynn Jackson, scorned and maligned by some for his years of employment by the Bureau of Land Management (and author of “The Wilderness Quandary” in the October/November 2011 Zephyr), told me of going to inspect environmental impacts from a seismic thumper truck. He recounted that a staffer from SUWA broke down and wept when she saw the damage. It was that painful to see.

But who are we railing against and wailing for? Are we angry on behalf of the rocks and the critters that reside there? Do we fear the damage done is irreparable? Do we stand foursquare in defense of the flora and the fauna? Or is it something else? Is it something far more complicated? Is it because something has offended our visual sensibilities…is it because we hate the way it looks?

In part, at least, that’s exactly the problem—It’s the aesthetics.

Over the decades I’ve witnessed the utter devastation of desert and alpine landscapes—blasted and tortured, wasted by everything from high density oil and gas development to sardine-in-a-can condo projects to multi-acre tourist parking lots. I’ve observed public lands grazing allotments so decimated by overgrazing that I cannot, for the life of me, figure what the cows are still nibbling.

And I’ve seen disturbances like these on a lesser scale. I’ve found old miners’ cabins and old bore holes and rusted machinery and piles of tin cans from a sheepherder’s camp and I’ve noticed that, once humans leave a place alone, the cacti and the critters come back and re-claim residency. Sometimes the reclamation comes quickly; at other times it takes a comparison of photographs shot a century apart to see the improvement. But I always marvel at Nature’s ability to heal itself, as long as we just leave it alone.

Twenty years ago, when I was still rangering at Arches National park, three of us built a wire fence across Salt Valley to keep out the sheep. Within five years, we could see the improvements.

What was it Terry and Renny Russell said in “On the Loose?”

“The weed will win in the end boys…The weed will win in the end.”

It’s cold comfort to many, including me. Trying to find relief in generational time, or even geological time, does little to soothe my anger when I see these kinds of impacts, whether I know I contributed to them (via my own consumer appetite) or not.

But many environmentalists can’t seem to admit that the “weeds,” left alone and given time, will outlast and repair even our most devastating human actions. Recently, former Utah Congressman Karen Shepherd spoke out against a recent Obama administration decision regarding wilderness and on behalf of the Redrock Wilderness Bill: “In a shocking about-face,” Shepherd wrote, “Salazar has rescinded his Dec. 22, 2010, order which had reversed President George W. Bush’s policy of not managing wild lands to preserve their wilderness character.”

The decision rocked the environmental community in Utah; it had waited 30 years for a sympathetic Democratic presidency and a filibuster-proof Senate to move its wilderness plan forward, and it had still failed to make headway. Now, with the Republican midterms sweep, chances for wilderness look even more dire.

Shepherd noted that conservative politicians seemed to have little sympathy for Nature: “They are not bothered by the reality that a high percentage of the roads and wells are eventually abandoned, yet forever remain scars on the desert landscape. They say they love the land and I believe them. But I also believe their bias makes them blind to the wildlife habitat being destroyed, to the plants and forests being altered, to the air and water being affected, to the quality of wildness evaporating.”

This is what the dictionary has to say about the word ‘destroy.’

1. To ruin completely; spoil.

2. To tear down or break up; demolish..

3. To do away with; put an end to.

4. To kill.

5. To subdue or defeat completely; crush.

And this is what it says about ‘forever.’

1. For all future time; for always

2. A very long time (used hyperbolically)

“Destroy Forever” and the aesthetics of the Land lie at the real heart of the wilderness debate. Or at least it appears that way when the threat to wildlands is mineral exploitation and extraction. Regarding oil and gas development, Ms. Shepherd also noted, “…statistics show (that) these revenues make a relatively minor, short-term contribution to the state’s economy, compared to the significant, ongoing contribution of the outdoor industry,” comments that reflect the sentiments of almost every mainstream environmentalist in the West.

Here’s what bothers me. First, the idea that these impacts are forever and irreversible is absurd and environmentalists know it; in fact, their expansion of proposed Utah wilderness in the last decade makes that very point.

When the Utah Wilderness Coalition expanded its wilderness proposal by more than 4 million acres a few years ago, virtually doubling the size of the original wilderness bill, where did they find all that land? Much of the Citizens Inventory was based on the idea that impacted wildlands could heal, that scars would diminish and that an old strip mine or an overgrazed pasture still qualified for wilderness if it was no longer in use. If SUWA can still find wilderness qualities in bore holes and strip mines, then we can hardy claim that such lands are “forever destroyed.”

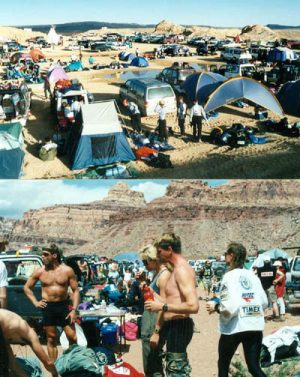

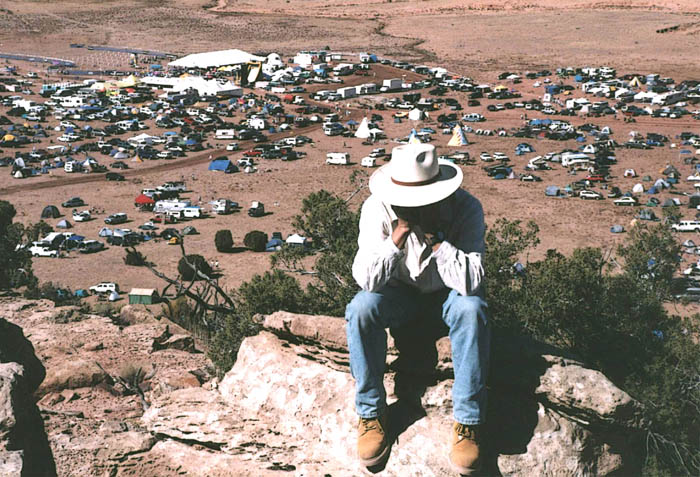

Second, while mainstream Greens worry about the aesthetics of ATV abuse and oil and gas impacts, they support an “amenities/recreation” economy and an “outdoor industry” that, by definition, requires the massive consumption of natural resources. It encourages a human migration to the driest most inhospitable part of the country–the American West–and does little or nothing to deal with the long term threat of Climate Change, the one long term threat that indeed may be irreversible. If anything, the movement’s almost silly and hypocritical lip service to the issue has worked counter-productively to turn a majority of American sentiment against the environmental “movement.”

The four fastest growing states in America can be found in the arid Southwest; yet try to find a message from environmentalists urging a stop to this kind of migration. Green groups are silent because they look at these migrants from the east as allies.

Constant sustained human activity, whether it be intense commodities development and exploitation, or exploitation with a “human face” (environmentalists’ beloved amenities economy), is what ultimately destroys the very plants and animals we claim we want to save.

Finally, environmentalists seem to be picking and choosing when they will allow the aesthetics of Nature to disturb them and when they will not. Often, the same ‘devastation’ delivered via a more ‘green-friendly,’ politically-correct means, somehow gets a pass.

The push by the Obama Administration, with the blessings of Mainstream Greens, to pursue alternative energies on a grand scale has caused some to wonder if “aesthetics” really plays a role here. The Interior Department is in the process of leasing vast acreages of public land for the development of wind and solar projects. While there is still serious debate that these options can even begin to make a dent in our insatiable hunger for energy, the subsequent environmental damage to public lands cannot be understated. And yet suddenly, environmentalists don’t seem to notice…or care.

Kevin Emmerich and Laura Cunningham, founders of the very grass-roots group Basin and Range Watch have recently wondered where their allies went. They’ve been fighting plans to exploit large parcels of desert land in Nevada and California from solar projects and have felt a bit lonely. They noted recently:

“Seems like 20 or 30 years ago, folks were concerned about protecting their local places, that specific mountain, the river nearby, those particular named canyons near where they lived, and the wilderness they hiked in. Today the shift among environmentalists has highlighted the global, the abstract, even the corporate model of “saving the Earth.” We are often lectured by this new hybrid of industrial green energy environmentalists about how our attempts to slow down these large industrial energy developments will expedite the warming of the planet and the extinction of the polar bear. We find it ludicrous that these same people would support actions that could lead to the extinction of species like the desert tortoise in an attempt to save the polar bear. Who told them that they were justified in choosing which species get to survive and which do not?”

Last year, they attended a local BLM scoping meeting for the NextLight Silver State South project. They could not help but notice all the empty chairs. Their old nemesis, the ATV crowd, was there in full force to protest the construction and to be speak in defense of the desert tortoise, but members of the green community were conspicuously absent.

Emmerich and Cunningham observed, “One by one, the big name environmental organizations fell like Dominos. The Sierra Club, National Resources Defense Council, Greenpeace, and the Wilderness Society have all taken the position of “develop the desert or doomsday”. They seem outright convinced that development and complete removal of these ecosystems is an essential move we must make to curtail greenhouse gas emissions.”

Even the night skies are in jeopardy as “alternative energy” projects expand across the landscape. Hundreds and thousands of wind turbines are now being proposed, planned and built across the Great Plains and the Intermountain West. What will their effect be on the wildlife? Nobody really knows. Already, clearly, the “aesthetics” of these projects are taking their toll, even at night, as red lights blink constantly in what was once an undisturbed and pristine night sky. So much for the aesthetics of a harvest moon on the West Desert.

In the end, despite the contradictions and the hypocrisy, do aesthetics matter? Of course they do. Would we ignore graffiti on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel? No. But would we only complain if the vandals used ‘red’ spray paint? Would ‘blue’ somehow be an acceptable alternative?

And would we have the right to condemn the vandalism of the Sistine Chapel if we were off elsewhere, painting mustaches on the Mona Lisa? This is precisely the hypocrisy of the environmental Left when we go ballistic over one form of vandalism while turning a blind eye to others.

Yet the message being delivered by mainstream environmentalists is clear— that the damage to the West from an oil well or a seismic track or a cattle allotment is irreversible and “forever,” while the development of a tourism-based “New West” town with its sprawling motels and fast-food chains and “adventure” tour companies and rent-by-the-night condos and insanely inflated housing prices are positive, impact-free contributions to the future of the American rural West.

Likewise, we are supposed to swallow the idea that thousands of acres of public lands, bladed and denuded of all living things and then plastered with “alternative energy” solar plants and wind turbines is somehow an inoffensive alternative to the extractive industries we’ve all supposedly come to hate.

Recently High Country News editor Paul Larmer wrote, “A couple of decades ago, the West’s conservationists dreamed a lovely dream: The region’s traditional extractive industry base, which had taken such a huge environmental toll, would soon make way for a kinder, gentler economy based on protecting the land for recreation and tourism.”

He acknowledges that it’s now clear—the extractive industry is alive and well in the West and likely to remain so for decades. But he insists, “Conservationists may not always be good prognosticators, but their dream of a vibrant economy that lives lightly on the land is still worth pursuing.”

Larmer predicts, “The amenity economy will rebound over the next few years to run full-speed alongside the new extractive rush.” And he concedes, “then we will have to deal with the excesses of both kinds of economies.”

I don’t think that’s the dream he originally had in mind. As the philosopher once said, “Be careful what you wish for…you just might get it.”

Aesthetically speaking, an overpopulated, over-priced, over-hyped “New West” will prove to be far uglier than the scars he complains about now. The hard truth is, there is nothing “kinder and gentler” about the amenities economy.

At the end of the day, if I had to bet which heals faster, a seismic track or a faux stucco condo development, I’d put my money on the thumper trucks every time.

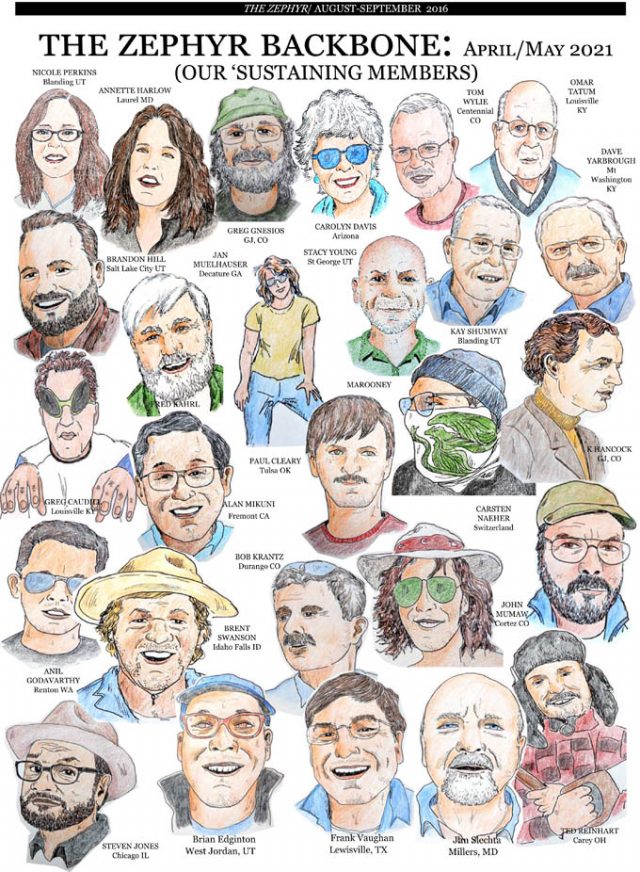

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Aesthetics are essentially selfish, at least in the sense that we can only use our personal senses and experiences to make judgements. And in many ways, how we perceive things is extremely limited, if not biased.

Take time. What is a long time? And what is a long enough time to use when pondering forever?

Here’s an exercise to help your sense of time, one that I have used when teaching about geologic time. Go the the office supply store and buy a ream of paper. Open the package of 500 sheets and discard (or use for origami or doodling) 43 sheets. The remaining 457 sheets each represent 10 million years of time, 5 million years on each side. Now number all the pages, 1 through 914, and note where (when) these earth history milestones occur:

Formation of the solar system (4,750,000,000 years ago), page 1

Formation of the earth (4,650,000,000), page 3

Earliest life (3,800,000,000), page 155

Oldest fossils (3,480,000,000), page 219

Buildup of oxygen in the atmosphere (1,850,000,000), page 545

Earliest sexual reproduction (1,200,000,000), page 675

Cambrian “explosion” of animal life forms (542,000,000), page 806

Earliest dinosaurs (233,000,000), page 868

Navajo Sandstone deposited (191,000,000), page 876

Entrada Sandstone deposited (165,000,000), page 882

Cretaceous interior seaway floods most of western US (100,000,000), page 895

Cretaceous seaway recedes (60,000,000), page 903

“Original” Rocky Mountain uplift (50,000,000), page 905

Volcanic centers at La Sal Mtns, Henry Mtns, etc. (30,000,000), page 909

Renewed uplift of Rocky Mountain and modern topography (6,000,000), page 913

Start of Pleistocene ice age (2,600,000), page 914 (about half way down)

Now for the stuff that we think is about us, we have to divide the page into 50 lines, each representing 100,000 years, each line into 20 words, each representing 5000 years, and finally each word into 5 letters, each representing 1000 years.

Homo sapiens (300,000 years ago), page 914, line 48

Start of most recent glacial period (90,000), page 914, line 50, word 2

Start of most recent inter-glacial warm period (12,000), page 914, line 50, word 17

Start of recorded human history (5000), page 914, line 50, word 20, first letter

Human population over 100 million people (2000), page 914, line 50, word 20, 4th letter

Human population over 1 billion, steam power (200), page 914, line 50, word 20, 5th letter

You and me, the period at the end of the sentence.

Now, what is a long time?

The environmental movement deserves a lot of scrutiny and we should hope for some meaningful change and special attention to the issues brought up in this essay. As environmental policy twists and turns and makes some undeniably wrong moves, the gas and oil industry will continue to have a large effect on political players and policy as well, and all while procuring record-making profits that benefit but a few. Both “sides” have a seeming lack of accountability; however, I am not ready to return our overcrowded wilderness areas and precious desert landscapes over to any industry just yet, be it gas, oil, mining, “environmentalism,” or tourism. It is terrifying and disheartening to watch as much of our populous branches out from cities and conducts business from what were once sparsely populated areas. Is this phenomenon due solely to the overreach and not-well-thought-out environmental policy, or to the gas, oil, and mining industry of canyon country, or perhaps due in part to technology that enables many more of us to work from far afield? Much of the complexities of land use issues are related as well to the population doubling in the last fifty or so years. While I agree that environmentalism as a movement has contributed to usage of canyon lands that we really didn’t want, I’m not sure I’m ready to agree that other industries mentioned here over time would have had a less deleterious affect on our current overuse and misuse situations. But, no matter who or what is at fault, ultimately we all suffer the consequences. It’s sad my children will not experience the “desert solitaire” I did at their age.

See my comment below. It isn’t about your children. It’s about the once exquisitely balanced ecosystems of the deserts. If we want to make living amends for what our species has done, we need to begin by understanding that we are “part of”, not the “center”” A critical step might be to control our tendency to breed.

Mary, thanks for pointing out that it isn’t about my children. Please know I was speaking somewhat metaphorically. While I’m with you that the planet population boom wrecks us, we have to look at what we face currently. I’m grateful to have lived and ventured in many wonderful places, and lament that all is at risk. I’m just not sure how we make a dramatic change in lowering population without addressing simultaneously the current issues that come with overpopulation. In recent history, have seen cultural paradigm shifts take effect. Fingers crossed we will see a global acceptance that our population needs to be curtailed.

“Agent Smith: ‘Human beings are a disease, a cancer of this planet. You’re a plague and we… are the cure.’ – Matrix” Not only is my species – and I – a virus, we are a narcissistic consumer virus. We eat “views” and “gorgeous landscapes”. We move to the desert and build multi-thousand square foot houses with huge windows – so, I suspect, we can have the feelings of wildness that we had when we first saw the desert on one of our carefully curated adventures. And now, Instagram has annihilated even that.

My species – and I, by association or genetics – are pathetic, and we are the greatest danger our home planet has ever faced.

While I agree that energy development (both fossil fuel and renewables), ranching, residential developments, and the recreation economy all contribute to degradation of the aesthetic, physical, and biological values of Western rural lands, there is one overriding threat that needs to be hammered at ad infinitum. And that is uncontrolled human population growth. Until human population stabilizes, or better yet, starts to decline, attempts to preserve rural land are doomed to failure. Problem is that most humans refuse to limit their family size to zero or one child. Therefore, the earth is screwed!

Seems you struck a nerve with this one Jim

From an environmental perspective the world is not made of states, regions, or countries, it is made of oceans, continents, and islands. The lifestyle we enjoy in the U.S. is not supported by what is within the confines of our borders, but by the extraction of resources and the distribution of waste/toxins around the globe. Currently the modest U.S. income, and its associated ability to consume and pollute, of $30,000/yr is enjoyed by only slightly more than 1 billion folks. Most of the 6.5 billion other folks would love to have even half that, and a good many are striving towards it. Along with who decides btw polar bears and desert tortoise, who decides btw you and one of 7.7 billion other folks gets to drive a vehicle around at their pleasure? We are all on the same island, how do we share and get along? Obviously there is no plan, and despite the current administration’s efforts to make things a bit more equitable, it falls way short of making much of a dent for all of us on this “island.”

Preserving as much biodiversity as we can, while plummeting towards a mass extinction is not about having a bleeding heart for our favorite endangered species as much as it is about buying time until we mature enough as a species to come into balance with this habitat we call home.

The Oil Industry realizes combustion engines won’t be trending much longer, and are shifting to more plastic production, yet there is no place on the planet, including your bowels, where plastics can’t be found. As we lose biodiversity and permafrost, and encroach on the remaining undeveloped bits, we also increase the likely hood of exposure to future viral pandemics. What fun that would be. Head in the sand won’t get us out of the hole we’ve dug, we need to make some tough decisions. Nobody wants an oil well, a plastics refinery, a nuclear reactor, or waste repository in their backyard, and where isn’t there someone’s backyard. Those thumper trucks lead to rigs and wells, then abandoned wells. Which lead to the problems laid out in this Grist article: https://grist.org/energy/abandoned-oil-wells-texas-railroad-commission/ – only make that more like 30 million abandoned wells worldwide, potentially emitting methane and fouling ground water. I grew up in the oil patch, worked there from age 15-22 in several aspects, as did dad and both grandads. I know what goes on there, unseen by the public.

I feel so lucky to have been able to lead a charmed life, but I don’t see a way for it to continue w/o having to give some things up. The thing is, 40 years ago, when I was enjoying the bliss of living in Canyonlands or on the Middle Fork of the Salmon, I knew those days were numbered, that access would become limited, reservations required, and that crowds would diminish the experience. It makes me sad my kid won’t be able to have the freedoms I did, but what can I do, besides be an informed citizen and take actions to minimize my footprint, and let others have a wee taste of what I did.

Thanks Jim great stuff!