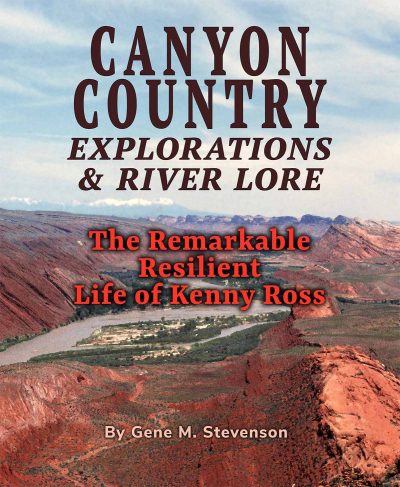

The following excerpts are from the book: CANYON COUNTRY EXPLORATIONS & RIVER LORE: The Remarkable Resilient Life of Kenny Ross, by Gene M. Stevenson. The book was written about Kenny Ross, one of the forgotten personalities on the Colorado Plateau whose major influence on river running in the Southwest had been previously overlooked. This story concerns several other types of field trips, some of which were not planned, but itineraries were adjusted on the fly due to unpredictable circumstances.

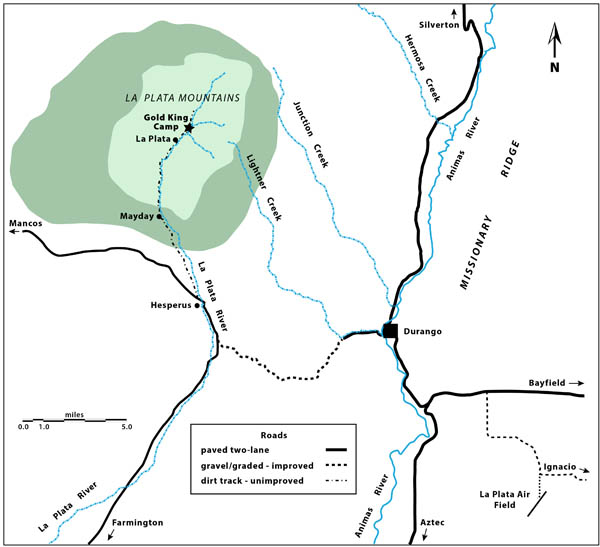

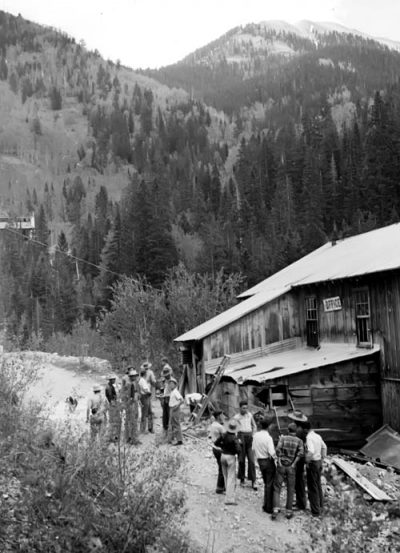

Ansel Hall, of Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley Expeditions fame, decided to start a camp for teenage boys in 1944, and ended up purchasing the old abandoned Gold King mine’s mill site located high in the La Plata Mountains in southwestern Colorado and converted some of the buildings into his base camp for field excursions.

The first two years were a mish-mash of disorganized field trips and outings for the boys who enrolled in his camp. Most were from relatively well-to-do families from cities across the country that had some relationship to Ansel’s efforts as the leader of the RBMV expeditions from 1933-38. But it wasn’t until the late summer of 1946 when Kenny Ross was hired by Ansel that the “Explorers Camp for Boys” started to include organized, truly adventurous hikes into the back country in the canyons in southeastern Utah.

Kenny was promoted to Camp manager in 1947, and the trips blossomed into a variety of activities for the boys. It was that year when Kenny convinced Ansel to buy some military surplus inflatable boats so that river trips could be added to the itinerary of activities, with particular emphasis on running trips down the San Juan River. Ansel agreed, but the military surplus bug bit Ansel, and he decided to investigate another type of vehicle that might fit his dreams for yet another form of field tripping – retracing the route of the Escalante-Dominguez Expedition of 1776. [Details regarding this adventure is not included here]

In January 1948 Kenny and Ansel made a trip to southern California where they spent two weeks buying equipment for the camp and the Mesa Verde Company. They bought four hundred pounds of “prime dates” to supplant raisins for knapsack trips. While in Santa Ana Stuart Maule found a DUKW at Bascom Rush’s military surplus business and they test drove it and ended up purchasing it for “slightly less than one-fourth its original cost of approximately $9000.”Kenny described his experience to Jon Lindbergh:

A big (31 foot) Army amphibious ‘Duck’ parked—or docked— at the curb in front of a used car dealers place and, never having seen one close up before, we stopped and looked it over. It was brand new– only 300 miles on it—and the price was rediculously low sooooooo—- yep, you guessed it—we bought the durn thing for use on the roving expeditions. It has lots of road clearance, lots of space in the bilges and holds–fore and aft–to stow supplies and equipment and the cockpit (13×8 feet) is plenty big enough to comfortably seat the 20 fellows who will be along on any one trip.

When I spoke of road clearance, I meant both that it has it and it does it. While trying it out I drove right up the main business street of Santa Ana and had no traffic problem at all. Drivers of other vehicles took one startled look and—dodged. What sort of psychosis it will produce in the Navajo Indians and their horses remain to be seen. A 31-foot motor-ship cruising though Monument Valley may be a bit startling. Seriously though, it handles as easily as an ordinary truck, provided you carefully calculate the overhang of the bow, and— I Think—-it will prove a very practical piece of equipment for our land cruises. It’s now being painted blue and gold with white decks and an awning is being made for it that will make it look quite ship-shape. Its name is to be the “Motorship Gila Monster”.

In late March the whole Ross family (Kenny, Mildred, Don and Doug) drove in Ansel’s old Ford sedan to California. The car broke down en route near Gallup, but following repairs and with no further problems they arrived in California at Kenny’s sisters’ place. The next day Kenny picked up the brand-new Army amphibious “Duck” (now painted blue and yellow) and left the old Ford sedan at the dealership. The DUKW was then formally boarded by the Ross family and the “Motorship Gila Monster” would forever remain its name. Although Doug Ross was only two-years old at the time, he recalled family photographs at the beach at San Luis Obispo in April, 1948, even though the city of Santa Ana was south of Los Angeles and questioned why they were there. Why did they go that far north of Los Angeles? Bill Dickinson provided the answer in an email in June, 2015:

I met Kenny in the winter of 1948 when he was prospecting for Explorers Campers with his DUKW in California. Signed on as a camper in 1948 and counsellor in 1949. If memory serves, ran the San Juan from Shiprock to Bluff the first year and then from Bluff to Lees Ferry the second year (came back just for the latter run in 1950 and 1951, again if memory serves). So ran Piute Falls and the Thirteen-Footer with him three times (eat your heart out).

The four members of the Ross family drove the DUKW back to Mancos following Route 66 out of California to Gallup where they turned north and returned safe and sound back in Mancos, Colorado. Don Ross recalled that many eyes were turned as they cruised eastward out of Los Angeles. Doug and Don both confirmed that it didn’t go very fast [45 mph tops]. Ansel may have traded the Ford in on some buses as Bill Winkler and his wife, Merrie [Hall] Winkler told me that the two of them drove one of the buses back to Mancos in 1948 following the same route that Kenny did. It’s possible that Ansel and Stuart Maule drove the other two buses.

Bill Winkler said that when the DUKW had arrived back in Colorado, Roger Hall and a friend took it out on a lake for a test run. Bill watched from shore and noticed it had listed strongly to one side and motioned the boys in. When they drained the water-logged amphibious craft, they noticed that three of the four drain plugs were missing! Bill made the necessary repairs to plug the drain holes and they never had another problem, but he laughed when he told the story as they came mighty close to sinking the Motorship Gila Monster before it was officially used.

The DUKW was used in June, 1948 in retracing the 1776 expedition route from Santa Fe of Spanish Explorer Fray Padre Francisco Silvestre Velez Escalante and Francisco Atanasio Dominguez, in their search for a route to Monterey and a San Juan River trip plus a strenuous and harrowing hike from Elk Ridge down into Beef Basin and following Gypsum Canyon all the way to its confluence with the Colorado River and safely returning to the DUKW and back to Explorers Camp in La Plata Canyon, but you have to read my book to find out what happened (see CH 5, p.132-138 for details).

THE “DUCK” STORY

The name DUKW comes from the model naming terminology used by GMC

- “D”, designed in 1942

- “U”, “utility”

- “K”, all-wheel drive

- “W”, dual rear axles

The DUKW (colloquially known as Duck) was a six-wheel-drive amphibious truck used by the U.S. military in World War II. Designed by GMC, the DUKW was used for the transportation of goods and troops over land and water. Excelling at approaching and crossing beaches in amphibious warfare attacks, it was intended only to last long enough to meet the demands of combat. Surviving DUKWs have since found popularity as tourist craft in marine/aquatic environments. The DUKW prototype was built as a cab-over-engine (COE) version six-wheel-drive military truck, with the addition of a watertight hull and a propeller.

The final production design was perfected by a few engineers at Yellow Truck & Coach in Pontiac, Michigan. The vehicle was built by the GMC division of General Motors, still called Yellow Truck and Coach at the beginning of the war. It was powered by a 270 in3 (4,425 cc) GMC straight-six engine. It weighed 6.5 tons empty and operated at 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) on road and 5.5 knots (10.2 km/h; 6.3 mph) on water. It was 31 feet (9.4 m) long, 8 feet 2.875 inches (2.51 m) wide, 7 feet 1.375 inches (2.17 m) high with the folding-canvas top down and 8.8 feet (2.6 m) high with the top up. 21,137 were manufactured.

It was not an armored vehicle, being plated with sheet steel between 1/16 and 1/8 inches (1.6–3.2 mm) thick to minimize weight. A high-capacity bilge pump system kept it afloat if the thin hull was breached by holes up to 2 inches (51 mm) in diameter. A quarter of all DUKWs held a .50-caliber Browning heavy machine gun in a ring mount. The windshields were provided by GM rival Libbey Glass (Ford).

The DUKW was supplied to the U.S. Army, U.S. Marine Corps and Allied forces. 2,000 were supplied to Britain under the Lend-Lease program and 535 were acquired by Australian forces. 586 were supplied to the Soviet Union, which built its own version after the war. DUKWs were initially sent to the Pacific theatre’s Guadalcanal, and were used by an invasion force for the first time during the Sicilian invasion in the Mediterranean. They were used on the D-Day beaches of Normandy and in other battles. Amphibious beachheads were thought to be highly vulnerable to early counterattack as the landing units would deplete their ammunition and the supply system would not yet be established. The principal use was to ferry supplies from ship to shore, and tasks such as transporting wounded combatants to hospital ships or operations in flooded land.

Even in the 21st Century, DUKWs can be found as tour buses, or in parades and commonly painted in bright colors. If you look back at the Super Bowl parades in downtown Boston in 2018, you can find perennial Super Bowl QB – Tom Brady and his trusted fellow teammate Gronkowski showering their beloved New England Patriot fans with waves and smiles from a fleet of open-topped DUKWs.

EXPLORERS CAMP PROGRAM FOR 1949

The summer of 1949 marked the sixth field season of the Explorers Camp for teenage boys. Ansel Hall was still advertised as the General Director, and Kenneth I. Ross was the Camp Field Director. However, almost all the correspondence, brochures, itineraries and activities were now under the control of Kenny and by the time the summer camp rolled around, it was called the “Southwest Exploration Field Program” and precise dates were delineated for the camp activities.

The camp was scheduled to last nine weeks from June 21 to August 22. The itinerary indicated that the boys were to convene at Gold King base camp and do some mountaineering the first week before being divided into three “parties” where the main activities would include: a) the first time 225 mile-long river run from Bluff to Lees Ferry to be led by Kenny Ross; b) continued excavations at Cahone on the “Cibola City Ruin” led by Prof. Gordon Thomas of the University of California; and c) fossil collection and touring Navajoland was to be led by geologist Dr. Henry P. Zuidema of the University of Michigan. This last segment was to include the usual stop at Lukachukai to take part in Navajo ceremonies and watch the Navajo rodeo, or Entah. The parties would then rotate so each group of boys could experience each activity and then the final segment d) planned was for the entire group to head to the canyon country west of Monticello and split into two groups: one would explore from the mouth of Indian Creek up to Salt Creek Canyon and the other group would start at the head of Salt Creek Canyon and work their way down canyon where they would meet the group coming up canyon.

However, Mother Nature and a series of cancellations drastically altered the plans and itineraries for that year’s Explorers Camp. The winter of 1948-49 was an exceptionally big snow year which caused immediate problems for their orientation period in June; and both Dr. Zuidema (geologist) and Prof. Gordon Thomas (archaeologist) dropped out at the last minute and could not make it to camp. Kenny even tried to entice Dr. A.K. Guthe to return for the archaeology but to no avail; plus, the group of boys was much smaller, numbering only twenty-six. Ansel and Kenny had to make changes “on the fly” and they dropped the trip to Navajoland and Lukachukai since “the show there has deteriorated so much that it is no longer worthwhile considering the amount of trouble we have to go to get there.”

Bill Dickinson provided a little insight into his youthful years when he reviewed these letters and mentioned that he was quite disappointed in 1949 when he heard about not returning to Lukachukai. “When we went down there the year before I danced all night every night of the squaw dance with a pretty slick Navajo chick name of Jeanie and I was fishing for the future.”

Kenny was particularly happy to see Jon Lindbergh and Bill Dickinson’s return as they became his main camp assistants, and the post-camp Cataract Canyon river trip with these two was still scheduled, even if it was just the three of them, so all was not lost. Regarding the 1949 Explorers Camp, much of what followed was derived from a lengthy Explorers Camp Newsletter written by Kenny and sent out to parents that described the activities through Thursday, July 28, 1949.

All the boys arrived in Durango according to their schedules and were taken to Gold King base camp where Jon Lindbergh was placed in charge of the younger group of boys and Bill Dickinson was placed in charge of the older ones. The first five days were spent at the Gold King base camp in the La Plata Mountains shoveling snow out of the camp and then “climbing nearby mountain peaks, horseback riding, and working with Marshall Long, an old prospector, who demonstrated the techniques of panning for gold.”

“On June 27 [Monday], the group of older boys, led by field director Dave Sanchez, our horse wrangler, made the first reconnaissance of the snow-covered trails leading across the divide from our headquarters in the La Platas to our outpost camp site in Bear Creek canyon.” There had been so much snow that the main group of boys traveled by truck to the west side of the mountains and then by horseback and afoot into the Bear Creek camp by a lower trail that was not blocked by snow.

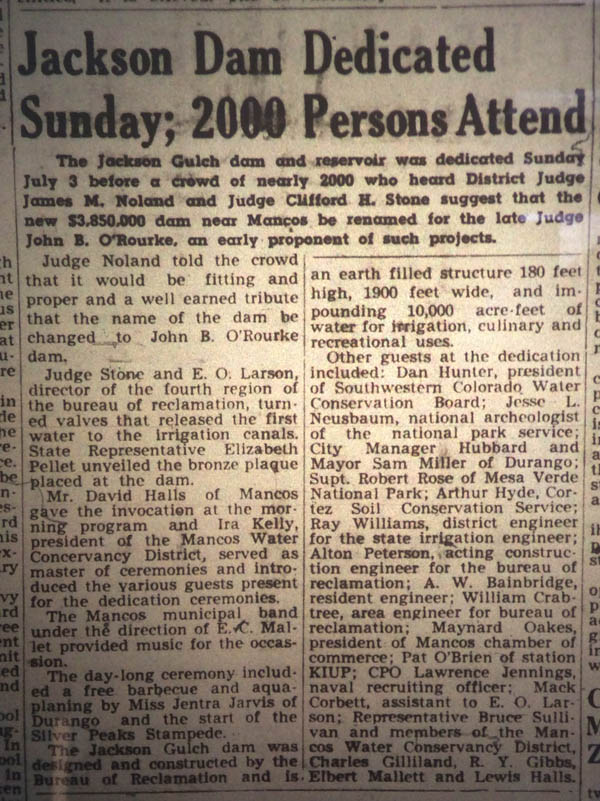

Meanwhile, Ansel Hall had learned that there was going to be a dedication of a newly completed reservoir that would provide much needed potable water to Mesa Verde National Park and the greater Mancos community. He made the necessary arrangements and the entire boys’ group was invited by Mancos residents to join in the 4th of July festivities which included the dedication of Jackson Gulch reservoir, a large irrigation project started by the Bureau of Reclamation before World War II and had been recently finished in late 1948.

The Jackson Gulch Dam

“The Jackson Gulch dam and reservoir was dedicated Sunday, July 3, 1949 before a crowd of nearly 2000 who heard District Judge James M. Noland and Judge Clifford H. Stone suggest that the new $3,850,000 dam near Mancos be renamed for the late Judge John B. O’Rourke, an early proponent of such projects.” (1949, July 7 Montezuma Valley Journal; p.1 and Cortez Sentinel, p.10) The Jackson Gulch Reservoir is located at an elevation of 7,825 ft.

Construction of the reservoir was approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941. An aqueduct runs nearly seventeen miles from Jackson Gulch Reservoir to Mesa Verde National Park, providing the major source of municipal water to the Far View Annex Visitors Center at the north end of Chapin Mesa as well as the Park Headquarters at Spruce Tree House. The park still receives most of its water from this reservoir.

The celebration included a big barbeque dinner at the dam site on July 3 and was attended by a couple of thousand people. The Explorers showed off the amphibious DUKW “the duck” by going in and out of the lake for several hours and the honor of plunging the “duck” into the lake for the first time was given to Jesse L. Nusbaum, Chief Archaeologist for the National Park Service and one of the dignitaries present for the big event. All the Explorers had a “turn at the wheel” while cruising. Bill Winkler inherited the DUKW some years later and stripped off the body and added “gin” poles for the powerful winch that was on the truck. He said it served him well for many years.

Unfortunately, due to continuous rain, the gold mining project was cancelled and on July 13 the group headed back to Gold King base camp to prepare for the big San Juan River trip that would take the boys all the way from Bluff through the lower canyons to the confluence with the Colorado River in Glen Canyon to Lees Ferry; a distance of some 225 river miles. But once again, their plans were significantly modified by Ansel Hall. Kenny tried to be upbeat about the altered plans that now had the group launching from Shiprock and only traveling as far as Mexican Hat. River trips to Rainbow Bridge and Glen Canyon would have to wait another year.

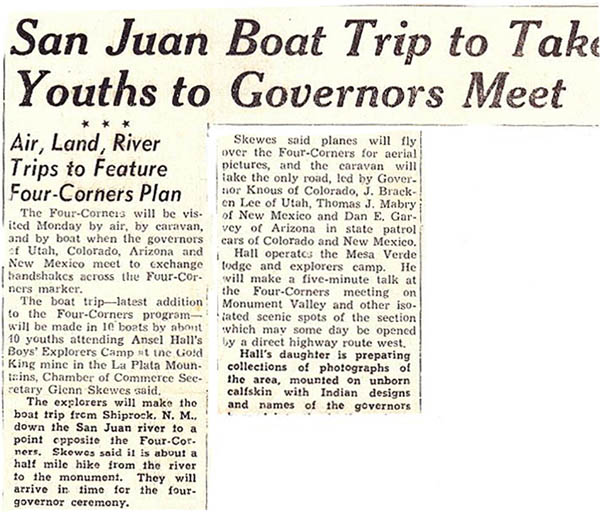

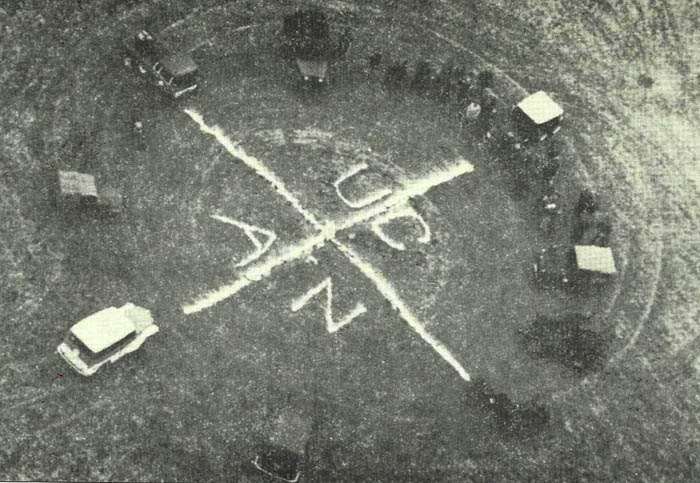

Upon our arrival we found that the whole group had been invited to attend the historic meeting of the Four-State Governors at Four Corners, the picturesque but desolate spot where Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado all meet with a common corner. Although, from a standpoint of transportation, this is one of the most remote spots in the United States, joining in the ceremonies fitted our plans perfectly since our river voyage would take us within one-half mile of the “Corners” monument where the ceremonies were to take place.

SAN JUAN RIVER TRIP: July 16-22, 1949 (The Governors Trip)

With food packed and boats loaded on trucks they set off for Shiprock, New Mexico on Saturday, July 16 and made camp. There was an Indian dance in preparation across the river and they all attended, but dancing didn’t begin until after midnight so they went back across the river and went to bed. By noon on Sunday the boats were loaded and they took off “on a five-mile current” and, on Monday, July 18:

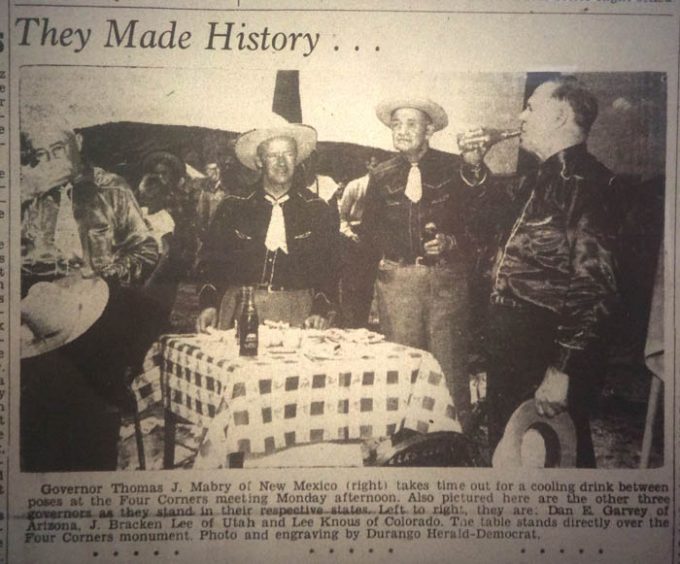

Their arrival at Four Corners was exactly timed with the arrival of the Governors and some 1500 other persons who came by plane, auto, afoot, horseback and, of course, by boat. It was terribly hot and since the State of New Mexico was passing out free Pepsi-Cola, all of us indulged in the ice cold beverage far more than was wise. “Chief” Hall met us there. He had arrived earlier by auto as he was to be one of the speakers.

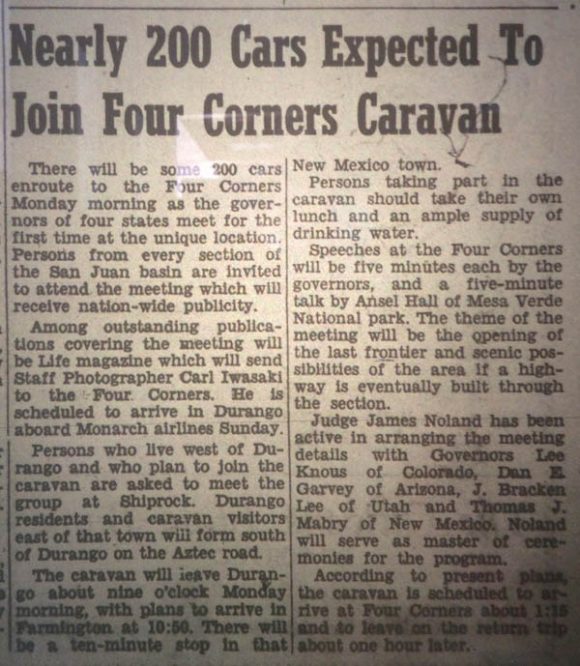

The big event was covered by area newspapers: “There will be some 200 cars en route to the Four Corners Monday morning as the governors of four states meet for the first time at the unique location. The theme of the meeting was to celebrate the opening of the last frontier and scenic possibilities of the area if a highway is eventually built through the section.” [Emphasis mine]

Kenny later wrote about this auspicious occasion:

A few years ago, the Governors of the States of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Arizona ate a ceremonial meal at a table set amid surroundings as strange and colorful as four such august gentlemen had ever encountered. The place was a barren, rocky flat rising above the San Juan River. The table was centered over a low cement monument which marks the spot where all four of the States meet with a common corner. This was probably the first time in all history that the leaders of four great political units had ever dined together while at the same time sitting each in his own territory. It happened in the only place such a stunt is possible – at the heart of the Four Corners Country.

Symbolic of the occasion, most of the two hundred-odd people who witnessed the event had reached this lonely place in the Southwestern desert by horseback, afoot, by auto and airplane. The twenty-six young men of Explorers Camp who attended by special invitation came by boat – after a two-day dash down the San Juan River.

At the time of this big event Kenny thought that further description of what occurred at Four Corners was not necessary since pictures and the story would be forthcoming in Life Magazine as they had sent Staff photographer Carl Iwasaki to document the event. The local newspapers showed photographs of the four governors standing around a table drinking Pepsi Colas at the monument and aerial photos of the crowd, but apparently Life Magazine didn’t find the event newsworthy. [Author’s note: There is no record of this event in any edition of Life magazine, leaving me to wonder if Mr. Iwasaki ever found his way to this remote location]

Following the ceremonies – Kenny and the boys returned to the boats and went down stream “a few miles” and set up camp and “after a hearty supper” they went to bed. They got underway the next morning (Tuesday) and stopped about 2:00 PM at the old Trading Post at Aneth, Utah where they had lunch and visited with folks at the Trading Post. A sudden dust and dash of rain storm hit and “tore our boats loose from their moorings, and sent them skittering across the water.” There was much confusion but the boats were rescued with little damage done other than one Explorer lost a camera in the water. They floated on downstream and set up camp near Bluff, with the intention of making a run into Bluff the next morning, but “there were a number of members absent from breakfast due to a sudden ‘intestinal looseness’ which had come upon the party during the night.” Kenny mentioned it might have been due to “our orgy at Four Corners.”

However, there might have been more to that. Think about this: they had a big barbeque feast at Jackson Gulch Reservoir, followed by the trip to Shiprock and going across the river to Indian dances where fry bread and mutton was more than likely eaten; then the next day they all made a hot hike to the Four Corners event and pounded ice cold Pepsi’s, followed by another “hearty supper” on the river followed by a stop at the Aneth Trading Post where the boys ate more junk food before making camp near Bluff. The combination was explosive to say the least. Kenny began referring to these intestinal problems as “the San Juan short-step,” but in later years he coined the term the “San Juan quick-step with fluid drive.”

Since everyone had gotten sick and dehydrated from the “scoots” they only traveled about three miles below Bluff before they stopped to “camp for the day and recuperate” [that put them at Sand Island where they laid over on Wednesday, July 20th].“Thursday morning everyone was fit as a fiddle and raring to complete our journey to Mexican Hat…” and through rapids and fast water and “miles of sporting ‘sand rollers’.” The last rapid [Gypsum Rapid] surprised the boys described as “a small but extremely rough one just above our final landing at Mexican Hat” immediately above the bridge on Thursday, July 21.

They de-rigged and the trucks showed up and brought yet more food, “a marvelous turkey dinner prepared and sent to us by the chef at Spruce Tree Lodge in Mesa Verde National Park.” They camped on the riverbank and the next morning they drove out to Goosenecks overlook and then back to Gold King via Bluff, Blanding, Monticello and through Mancos.

Then they spent “the next two days preparing for our archaeological trip for excavations at Cahone.” From Gold King, they traveled to Mesa Verde National Park to enjoy the hospitality of “Chief” Hall at Spruce Tree Lodge where “at this writing” [Thursday, July 28, 1949] they had just finished “the best fried chicken dinner we have ever eaten.” They left the next day to set up camp near the Cahone ruin where they were to begin excavation work. Kenny signed off by writing that they were well-fed and tanned and in good spirits.

One thing was certain – although the camp activities had been severely modified, Ansel had made up for it through food – these kids had eaten big meals all month!

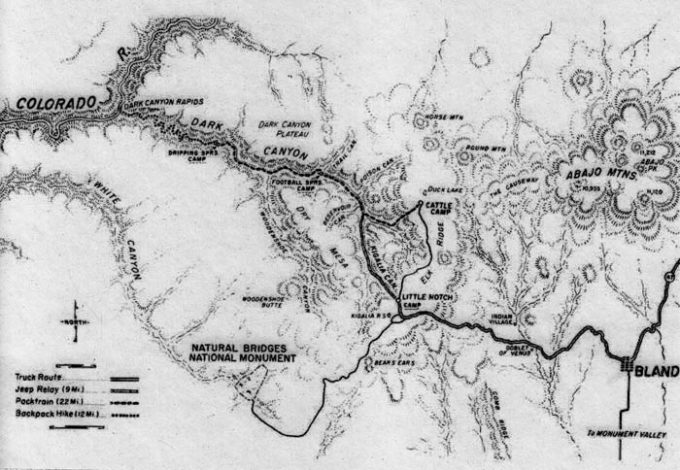

THE HIKE BEFORE CATARACT TRIP

The whole group worked together for an abbreviated session at Cibola City Ruins under the direction of Kenny Ross and departed for Elk Ridge on Thursday, August 4. The original plan was to split into two groups with one group hiking to the head of Salt Creek Canyon and the other group was to begin their hike at the mouth of Indian Creek Canyon and then the two groups were to meet in the middle. But Kenny was the only adult in the group so the plan was changed and hikes into Salt Creek Canyon would have to wait until the 1951 season.

The group of Explorers ended up hiking into Woodenshoe Canyon and down Dark Canyon to its mouth at the Colorado River. By now, Kenny knew this trek fairly well, having been there twice before – in 1946 and 1947. On this particular trek, Jon Lindbergh wandered up the river bank a mile or so to look over the rapids in anticipation of the upcoming river trip. Kenny recalled that Jon quietly came up behind Dick Griffith and said “Hi there!” and nearly scared him to death. Griffith had no idea any human being was within a hundred miles of him. Imagine his surprise?

For the rest of the story about the 1949 Cataract Canyon trip, see “KENNY ROSS AND THE 1949 CATARACT CANYON RIVER TRIP” from the June/July 2020 Zephyr, or buy the book HERE.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

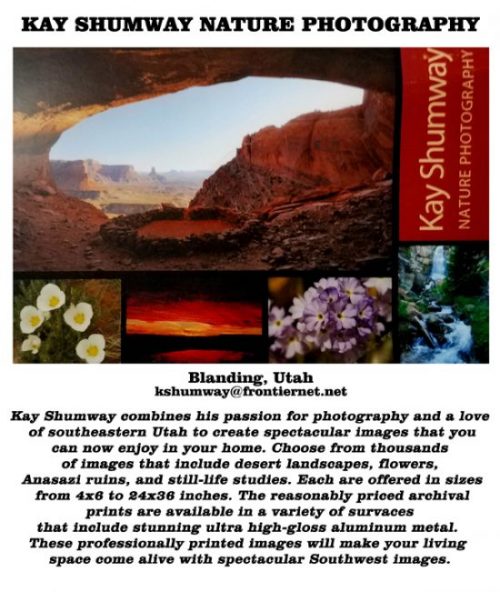

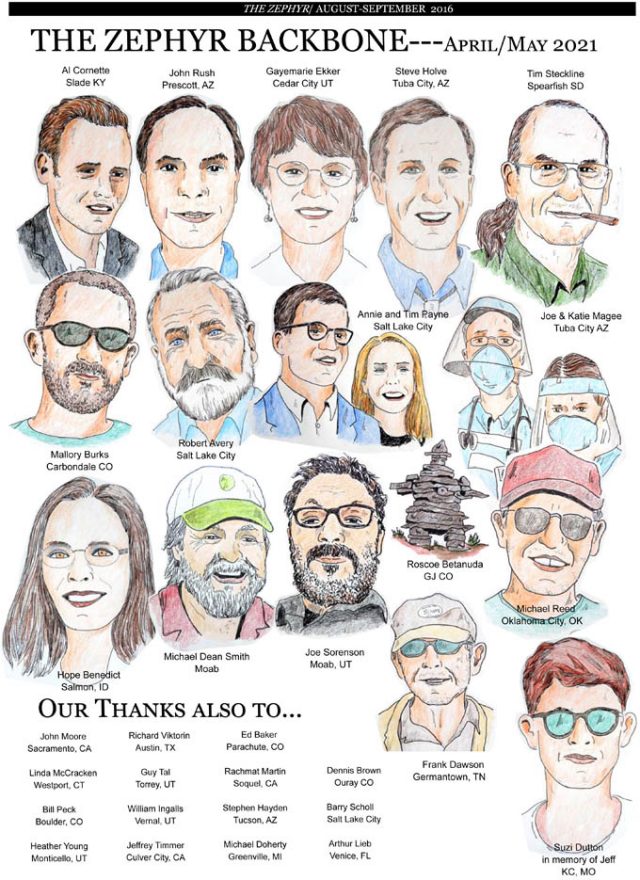

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

good lowered! aw lawt 2 wade thru’ — but this should prove a valuable treasure trove to historians of this era.