The Indians found it long before the white men came.

—John Wetherill, commenting on the discovery of Rainbow Natural Bridge

“The discovery of a natural bridge surpassing in size anything heretofore found is the news brought to this city this morning by Prof. Byron Cummings and party,” declared the heading for a front-page article in the September 3, 1909, Salt Lake City Deseret Evening News. The Utah Archaeological Expedition, led by Cummings, had just completed its summer’s work in southern Utah and northern Arizona on behalf of the University of Utah and the Utah Society of the Archaeological Institute of America. The climax of their trip was an arduous horseback journey into the wilds of the Colorado Plateau to locate a rumored geological marvel, which was to famously become known as Rainbow Natural Bridge. They were excited to share the newsworthy story of their success with the public. (For more on the 1909 Utah Archaeological Expedition, see my article, “Finding Value in Hardships,” in the April/May 2021 Canyon Country Zephyr).

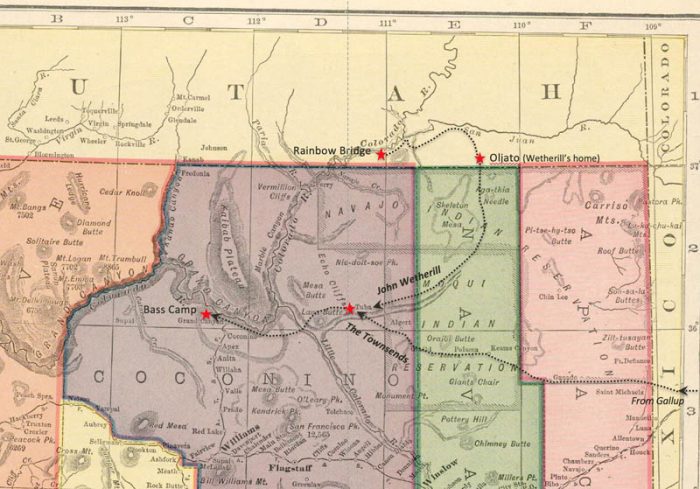

The Rainbow Bridge portion of the expedition entailed a strenuous horseback ride that began at the remote Wetherill and Colville trading post a few miles west of Monument Valley. The adventurers rode about 70 miles westerly across incredibly rugged canyon and mesa country, eventually circumnavigating the northern slope of Navajo Mountain and working their way down the meandering Bridge Canyon until they finally reached their glorious goal.

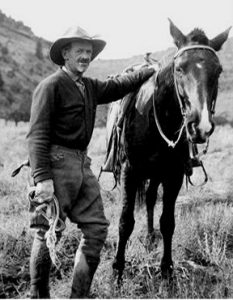

Along with Cummings were his 11-year-old son, Malcolm; students Neil Judd and Stuart Young; young artist Donald Beauregard; veteran backcountry guide and outfitter John Wetherill of Oljato, Utah (my great-grandfather); Navajo wrangler Dogeye Begay; and Paiute guide Nasja Begay. Also on the trek was a “rival” group led by William Boone Douglass, an examiner of surveys for the U. S. General Land Office. He was accompanied by his Paiute guide, Jim Mike, and assistants Daniel Perkins, John English, Jack Keenan, and Jean Rogerson from southeast Utah.

Some of the participants recorded the thrill they felt when first they gazed upon the bridge. “For moments we stood in silent admiration,” recalled Neil Judd. “The goal for which we had labored and endured much! It stood there before us, half hidden by the cliffs of which it formed a part. Human weariness, aches and pains were momentarily forgotten. We had attained the mystic stone rainbow; we had seen what few living men, white or red, had ever seen.”

The report of the Cummings party was welcome news to the people of Utah. Newspapers of the day routinely reported the latest geographical discoveries, usually in distant parts of the world. In January, 1909, Ernest Shackleton’s expedition located the South Magnetic Pole. In April, Robert Peary, Matthew Henson, and four Eskimo explorers came within a few miles of the North Pole. This was also the year that the state of New York passed a bill declaring Columbus Day a legal holiday to honor the so-called discoverer of America.

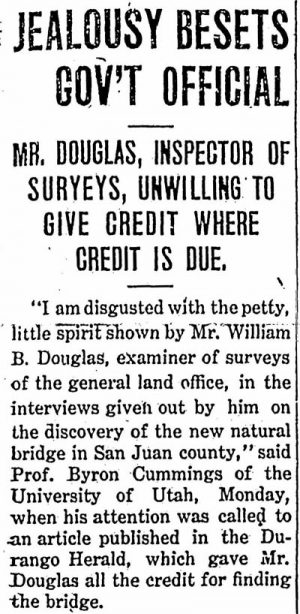

Controversies soon began to swirl around the story of the expedition. “The Greatest Natural Bridge in the World has been Discovered in Southern Utah by William B. Douglass,” declared a headline in the September 23 Cortez Herald. “Jealousy Besets Gov’t Official; Mr. Douglas [sic], Inspector of Surveys, Unwilling to Give Credit where Credit is Due,” countered an article in the October 1, 1909, Grand Valley Times.

Which white person first learned of the existence of the bridge? Which Indian guide knew the way? Which of the explorers first saw the bridge? Had other non-Indians been there before? Who first rode a horse under it? Which organization—the University of Utah or the General Land Office—deserved credit for the discovery? Beginning in 1909 and continuing up to the present time, writers have expounded on these questions, proposing divergent answers that are most often less than accurate and based on shoddy research. The more significant question, however, which seems rarely to be asked, is, “Why are these particular issues so worthy of endless disputation?”

In the case of these particular controversies, insights can be gained by considering the character weaknesses of William Boone Douglass. In his writings, he gave the members of the Cummings party no credit, claiming it all for himself and his Paiute guide. On the return journey, Neil Judd, of the Cummings party, graciously led him to Inscription House cliff dwelling and showed him the historic inscription for which it was named. Douglass claimed credit for discovery of the inscription. Referring to John Wetherill, he stated in a letter to Mrs. Wetherill, “I never saw any one who could get a party over as much ground in so short a time as he.” However, in his report to the General Land Office, he referred to Wetherill as a “packer.” Douglass lambasted Cummings for engaging in scientifically irresponsible excavations of archaeological sites, yet he did his own looting at Inscription House.

The disputes continued on and on, clouding the real story—the existence of an amazing natural wonder in the wilds of southern Utah. The ongoing preoccupation with questions such as these seems to be the result of a perverse definition of discovery, i.e., “the first sighting of, or visit to, something of significance by a white man.” Modern writers usually temper their discussion of the 1909 trek by placing quotation marks around the uncomfortable term, e.g., the “discovery” expedition.

From another perspective, however, discovery is, indeed, a legitimate word to describe the result of the 1909 quest, as one of its meanings is “to make known.” The expedition leaders were indisputably the first to inform the public of the existence and location of Rainbow Bridge and recommend its designation as a national monument. By virtue of those accomplishments, the 1909 expedition was, indeed, one of discovery and worthy of historical discourse. Nevertheless, the more interesting and significant story is that nature has produced such an awe-inspiring masterpiece rather than the manner in which humans became aware of it.

The government’s protection of natural wonders, by designating them national monuments and parks, helped bring the features to the public attention and enticed many adventurers to travel out to see them. In the case of Rainbow Bridge, visitors began arriving even before it was a national monument, despite the arduous journey that was required to get there.

In 2016, I learned of another amazing discovery involving the bridge. I received an email from a gentleman named Michael Rosch who was seeking information about an early excursion into the canyon country that involved John Wetherill. “I have 3 albums of extraordinary photos in several formats, many captioned, chronicling an expedition which documents many sites and situations in the 4 corners,” he wrote. Wetherill’s name appeared in some of the captions. Two other participants were not identified by name, but only by their initials: “A.R.T.” and “E.R.T.”

I asked Mr. Rosch where he had obtained the albums and was astonished by his reply. “There is a place at the municipal dump where people drop off household items […] that might be of use to someone else. It is only open 2 days/week and at the end of each day at 3:00 pm, whatever is not recycled is crushed by a bulldozer and carted off to the landfill. […] We live in an area where property values are very high and old houses are often sold and demolished along with their attics. I suspect the albums were cleaned out of an attic in an old house that changed hands.”

I recognized the initials as those of Arthur Rodman Townsend and his sister, Eleanor Rodman Townsend of New York. They are credited as the first tourists to make the long horseback journey to Rainbow Bridge only a month or so after the Cummings/Douglass expedition had been there. Based on a handful of Townsend photos in the Wetherills’ collection, I was aware that Arthur was the photographer and that the 1909 Townsend trip had also included a visit to the Grand Canyon. I was delighted to know that many more photos had survived. Mr. Rosch graciously gave me permission to share some of them with readers of the Zephyr.

The first album contains about 200 photos from two 1908 trips that included Mesa Verde National Park, Hovenweep and Natural Bridges (later to be established as national monuments), and El Morro National Monument. The other two albums contain 400 photos from the 1909 expedition to Grand Canyon National Monument, Navajo National Monument, and Rainbow Bridge. A review of the photographs revealed that they are an invaluable record of historic scenes on the Colorado Plateau, depicting horseback and wagon travel, routes and trails, camps, trading posts, tourist accommodations, and some of the pioneer residents of the region. Even in the absence of trip journals, the images and their captions tell interesting stories of the past.

Further research revealed that the Townsends were from New York City. Arthur had studied engineering at the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale College and the Colorado School of Mines and worked as a mining engineer in Colorado, Mexico, and Ecuador. When they began the 1909 expedition, Arthur was 32 years old, and Eleanor was 20.

The Townsends arrived in Gallup, New Mexico, by train, probably in early to mid-August of 1909. They then headed west by wagon to Tuba City, Arizona. Their photographs depict many scenes along their way, including the Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado and the Hopi villages of Walpi and Oraibi. In the meantime, their guide, John Wetherill, hurriedly traveled from Rainbow Bridge to his home and trading post at Oljato, re-outfitted, and proceeded to Tuba City. There he met the New Yorkers, and they began the Grand Canyon portion of their journey. They left the wagon and headed toward the canyon on horseback.

The register of the Bass Hotel, which was located in the western portion of the Grand Canyon, records that the explorers stayed there on September 3. They descended the South Bass Trail to the Colorado River accompanied by a burro train, and there they examined William Wallace Bass’s cable car that crossed over to the north side. The party also visited the other cable car across the canyon’s Colorado River—the one that had been installed two years earlier by David Rust to access his tourist camp, which later became known as Phantom Ranch. Their route took them to the head of the Bright Angel Trail, down to Indian Garden, then east along the Tonto Platform to the precarious “Tramway Trail.” This final section was the predecessor of the lower South Kaibab Trail. It ended at the southern terminus of Rust’s cross-river cable where the Black Bridge was later constructed. There the adventurers camped.

Also included on the itinerary was a visit to Pete Berry’s Last Chance Mine on Horseshoe Mesa at the foot of the Grandview Trail. The explorers then continued down the steep “old Coppermine Trail” off the east side of Horseshoe Mesa toward Miners Spring and Hance Creek.

Wetherill’s enthusiasm for the remote and spectacular Rainbow Natural Bridge must have inspired the Townsends to request that he guide them there, as well. They returned by horseback to Tuba City where they retrieved their wagon, then proceeded on to the northeast, camping along the way. At Marsh Pass, they made a side trip into Tsegi Canyon and visited the cliff dwellings of Betatakin and Keet Seel, which were within the recently established Navajo National Monument. John Wetherill served as its official custodian under the General Land Office. Several miles beyond that, the going got tough for the wagon, but the travelers managed to make it across the bad sections and pulled into the Wetherills’ yard at Oljato, Utah, just west of Monument Valley.

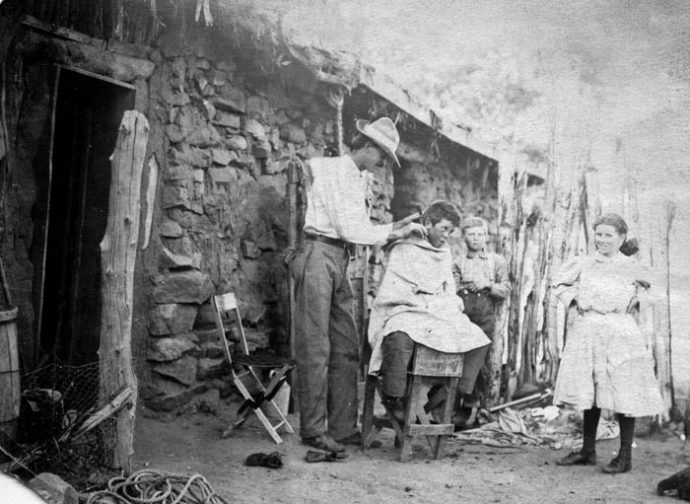

Spending some time at the Wetherill home and trading post allowed the Townsends to rest and become acquainted with other members of the tiny settlement—John’s wife, Louisa; children, Ben and Georgia “Sister;” the trading partner, Clyde Colville; and local Navajos who came to the post to trade. Then Wetherill and the Townsends saddled up again and headed into the wilderness toward Rainbow Bridge.

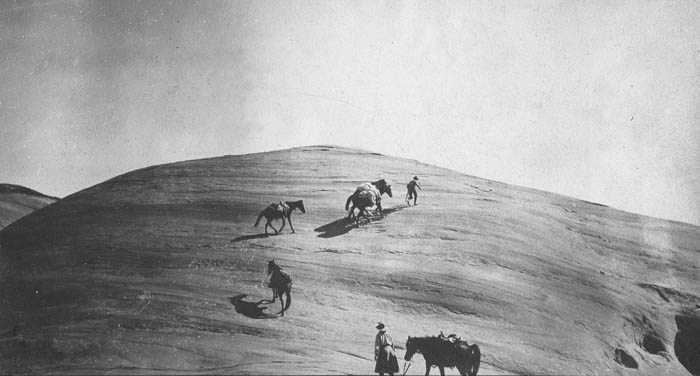

The difficulties and hardships involved in this next part of their adventure are inconceivable to modern visitors to the region, but Arthur’s photographs poignantly portray some of their challenges. Wetherill had no opportunity to build or repair trails following his first visit a month earlier. In some places, the travelers found it prudent to dismount and walk, less a misstep result in loss of both a horse and rider. The Townsends came up with names for sections of the route that particularly caught their attention—The Abomination of Desolation, The Inferno, and The Limit.

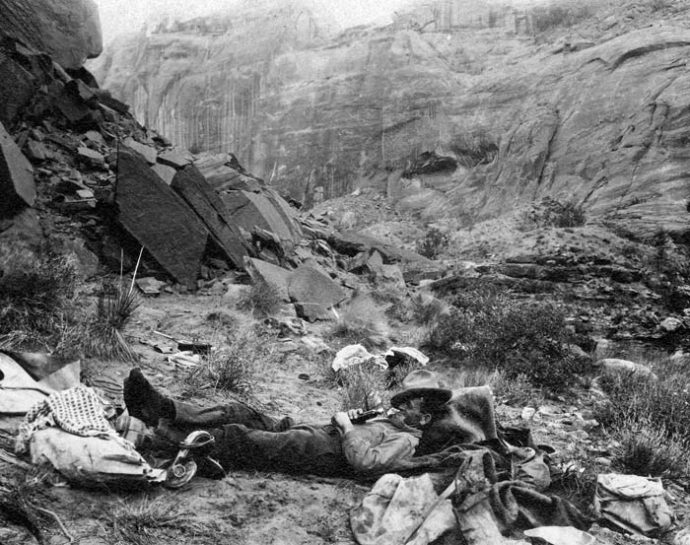

Despite their struggles, they successfully made it to the bridge and undoubtedly delighted in their accomplishment and the intense beauty they were privileged to experience. In good spirits, Arthur photographed Wetherill lying under the bridge with a whiskey bottle. Wetherill was a teetotaler, but he might have wished for a strong drink after all the difficulties through which he had brought the Townsends.

In 2009, I was asked to give a talk at Lake Powell as part of a celebration of the centennial of the Cummings/Douglass expedition. I entitled my speech: “Rainbow Bridge—A Century of Discovery: 1909 to 2009,” implying an even different meaning of discovery. I was referring to self-discovery, which has been defined as “the act or process of gaining knowledge or understanding of your abilities, character, and feelings.” A number of early visitors to Rainbow Bridge National Monument described these revelatory rewards of their trips.

In addition to the inspiration of the bridge itself, there was the rugged Rainbow Trail, stunningly beautiful but intensely challenging to folks who were not yet hardened to the rigors of wilderness travel. Their adventures stimulated the most perceptive ones to question the wisdom of their coddled, “civilized” lifestyles. Winifred Hawkridge Dixon, recalling her horseback journey to the arch about 1919, wrote, “We had a sense of courage toward life new to us all. The mere fact of our remoteness helped us shake off layers and layers of other people’s personality, which we had falsely regarded as our own and showed us new selves undreamed of.”

Another reward of the experience was the opportunity to observe and interact with Native American residents of the area—Navajos and Paiutes—who saw the world from a distinctly different perspective than that of mainstream society. An elderly Navajo sheepherder named Wolfkiller from the Monument Valley area told my great-grandmother, Louisa Wade Wetherill, about the training he had received from his grandfather and mother when he was just a boy that started him on “the path of light.” His family’s approach to life was radically different from the training that modern children receive. They honored their connection with nature instead of trying to distance themselves from it, and they learned important life lessons from keen observation of their natural environment rather than dwelling on artificial, man-made constructs. Wolfkiller followed the path of light during his lifetime of authenticity, integrity, kindness, and joy. (For more on his philosophy, see my article, “The Path of Light,” in the February/March 2020 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

In her book, My Name is Chellis & I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization, psychologist Chellis Glendinning contrasts the debilitating effects of technological society with the virtues of nature-based cultures. “We are constantly being told, and many of us believe,” she writes, “that we are superior to the natural world (and certainly to people who wear animal hides) and that our supercomputers, space shuttles, biotechnologies, and virtual realities will facilitate the final escape from our earthly origins.” In regard to our “sunny ethic of progress, which insists we are consistently growing smarter, stronger, heathier, and more evolved,” she observes, “Native and indigenous peoples have long wondered at the western way of being and seen it as it is, if not pathological, bizarre.”

In 2012 I served for a few weeks as a volunteer ranger at Rainbow Bridge. Most tourists now arrive by boat via Lake Powell and hike only a short distance along a well-groomed trail from the boat dock to the viewing area. Although their experiences are nothing like those of the early visitors who came there the long way, I was pleased to see that the bridge is still enticing folks to get outside and take pleasure in nature. I was particularly gratified to see adults with children and the looks of awe that were reflected on some of the kids’ faces. Such places are a much-needed antidote to stultifying urban environments where electronic devices, insipid culture, and artificiality dominate and nature is considered something to be avoided.

A few years ago, I was hiking out of the Grand Canyon on the Bright Angel Trail when I overheard some boy scouts chatting on the switchback above. “Wow, I think I could do anything!” one of them told his buddies. A short time later our paths crossed, and the same boy spoke to me. “Excuse me, sir. Could you tell me if this is a spiritual experience?” he asked.

“Yes, it is,” I replied. “Many people have had their lives changed by coming here.”

We can only speculate on the lasting benefits of their outdoor forays for members of the 1909 expedition, the Townsends, Winifred Hawkridge Dixon, the Grand Canyon boy scout hikers, and countless other visitors to natural places down through the years. Yet we can be assured that many of them were much enriched by their experiences, and, for some, their new-found insights also positively influenced their families and friends as well as the larger society.

Although there are critics who would play down the history of geographical discoveries, the stories of early explorations and adventures can provide profound insights into human nature.

They also serve as reminders of the passions of those who searched for America’s treasures and fought for their preservation through creation and management of parks and monuments. And awareness of the depth and breadth of meaning those natural wonders had for the generations of those who came before us can broaden the perspectives of modern visitors and enrich our own experiences.

.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer. Click here for more articles by Harvey Leake.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Love the Rainbow Bridge, and this article.

Thank you, Harvey, for lucidly exploring the many meanings of ‘discovery’ and for sharing a new treasure trove of historic photographs.

Another wonderful story by Harvey explaining the spiritual benefits derived from the exploration of nature and the thrill of discovery. Thanks!

There is mundane discovery, like finding something obvious (Rainbow Bridge). There is exceptional discovery, like finding something that requires far from obvious insight and intelligence (the speed of light and special relativity). And then there is novel creation (technology that confirms the speed of light and a relativistic universe).

And I would argue with Ms. Glendinning that technology-driven societies are indeed advanced in many ways compared to less technical societies, especially with determining universal scientific truths. We can debate other values, but truth is truth.

Love this article! “Arizona Highways” magazine ran an article with photos about Rainbow Natural Bridge in the July 2021 issue (“The Other Side of the Rainbow” by Morgan Sjogren, page 40). Morgan hiked to Rainbow Natural Bridge via the 18-mile North Trail for the article. One section of the article summarizes the information in this “Zephyr” article, including the mention of Harvey Leake!