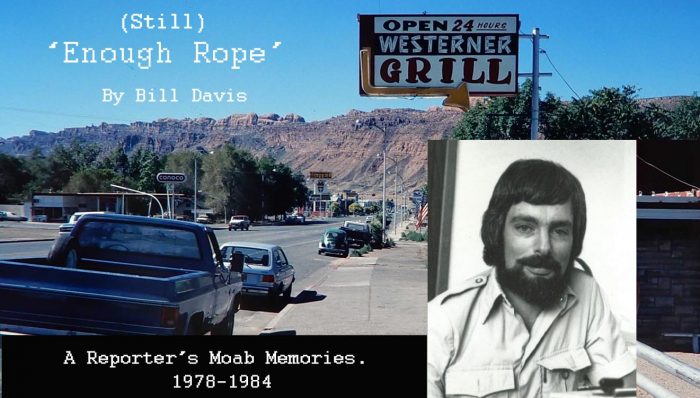

During my career as a mass communications/journalism professor, I spent many years also teaching a section of English composition. Students were required to write a weekly 500-word essay using various styles of academic writing. One of those assigned categories was Comparison and Contrast. Over the years, I have found that Comparison and Contrast also occurs naturally—outside the classroom. Let us go back to 1984:

It is difficult to adequately convey the shattering impact of Grand County’s uranium industry collapse in the early 1980s; it was ugly and painful. I was both chronicler of the disaster, and, ultimately, became one of many victims swept out of town by the economic tsunami.

Once the market price of uranium concentrate dropped below the cost of production (from about $45 per pound to $14), shutdowns and layoffs occurred quickly.

Unemployment climbed over 20 percent, into Great Depression numbers. A spokesman for Social Services told me at the time that about one-third of the houses in town were not only for sale, but had been abandoned by the owners. I know that the house next to my place on Westwood (for which I had paid a then-exorbitant $36,500) eventually sold for $17,500. Really.

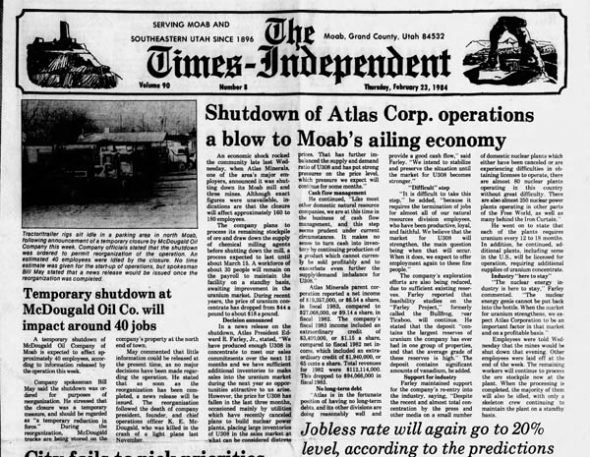

Here are the front-page headlines for articles I wrote for just one issue of The Times-Independent, Feb. 23, 1984:

“Shutdown of Atlas Corp. operations a blow to Moab’s ailing economy,”

“Temporary shutdown at McDougald Oil Co. will impact around 40 jobs,” and

“Jobless rate will again go to 20% level, according to the predictions.”

I remember that issue well, as it marked the decision point for my future. About a year before, T-I Publisher Sam Taylor had called a meeting of the entire staff, the first I remember during my years on the paper.

We had, he said, just lost advertising from one of the three grocery stores that ran in the paper each week. These multi-full-page ads were the lifeblood of the paper, so this was serious.

“If we lose one more,” he said, “someone will have to go.”

It was obvious the loss of another was highly likely.

Everyone looked at me. Of the four of us, I was the only member of the staff who wasn’t married, didn’t have kids, hadn’t lived in town for decades, and didn’t directly bring money into the operation. It was clear to all of us who would be departing.

I couldn’t even disagree with the decision; all of these people were important to me, and given my (sort of) youth, educational background, and history of bouncing around the country, I was the logical choice.

In a massive bit of irony, the Feb. 23 front page also included a photo of Co-Publisher Adrien Taylor and me holding awards from the Utah Press Association for 1983. I had won first place for both Best News Story (the pot plane crash) and Best Column (Enough Rope).

Adrien was smiling; I looked like my dog had just died.

I was grateful for Sam’s 1983 warning; during the intervening year, I considered applying to other small-town papers where I might want to live—someplace with red rocks—perhaps St. George or Cedar City. I quickly realized that not only did I not want to be a reporter in either of those towns, I flat did not want to be a reporter anywhere other than Moab. Any other community, larger or smaller, would have been a letdown. Some sort of radical change would be required.

So, Plan B: I had loved going to school at Utah State, and generally, enjoyed the academic atmosphere. How about becoming a professor? No more crawling out of bed at 3 a.m. to cover a fire, crime, or major accident, and I would actually get some time off. During six-and-a-half years at the paper, I had taken exactly five vacation days.

It wasn’t Sam’s doing; I was always afraid I would miss something major if I wasn’t around, so I limited myself to only an occasional weekend camping trip (which always ended up in the paper as a B-1 feature anyway). I did it to myself.

To demonstrate how extreme “life as the community’s reporter” got, I once received an offer from Mitch Williams, owner of Tag-A-Long Tours, for a free weeklong trip down Cataract Canyon if I agreed to swamp, and I turned it down. That’s stupid. I’ve been kicking myself over the decades since. Oh, and nothing happened during the week I would have been gone.

After five years of this, however, I was dancing dangerously close to burnout—even getting crabby around the office, which was distinctly out of character.

Sam directed me to take a week off, so Kris and I went camping, which, of course, resulted in a second-section travel feature on Ouray, Mesa Verde, and one of my favorite out-of-the-way spots, Hovenweep.

So, given impending burnout and possible layoff, back to school it had to be, again at USU, in a master’s degree program this time. By January, I had taken the Graduate Record Exam and applied for admission as a precautionary measure, in case the local economy continued its voyage south. Kris planned to return to college as well, to complete her long-delayed bachelor’s degree.

Also during January (And here comes the contrast, in case you were wondering), I got a call from Bill Groff. Bill, his brother Robin, and father John had opened Rim Cyclery in 1983, after they had all been laid off from their uranium industry-related jobs—Bill from his piloting job with Clayton Stocks Mining, John from his purchasing agent position at Moab’s Atlas Mill, and Robin, a mining engineer, from an outfit in Ticaboo. They were determined, however, to remain in Moab.

As the story of Rim has been repeated many times and become a legend in the biking world, I won’t reproduce it here, but I can say with personal authority, pretty much everyone in town thought the Groffs were nuts.

A bike shop? Where was anyone going to ride, given the limitations of the then-current road bikes? Heck, there were only four paved ways out of town: Highway 191 north and south, Highway 128 northeast up the river (a suicide ride if ever there was one), the Egg Ranch Road (which didn’t go very far), and the Potash Road on the north side of the Colorado River. That was it.

During the call, Bill described a new type of bike, “like a Jeep,” they had just started carrying that resembled an old-style cruiser: solid, with fat tires, but featuring good components, similar to those found on high-end road bikes, only with a much wider gearspread, and 15 to 18 ratios, rather than the traditional 10.

The call piqued my interest immediately. Although I hadn’t ridden in a while, I had been a hard-core road biker during my time at Utah State in the late 60s and early 70s. I had cranked off thousands of miles on my aluminum-framed, hyper lightweight Peugeot Pro, both in Utah and my home state of California.

Bill offered to lend me a couple of the new type of bikes over the weekend, so Kris and I could try them out, and I could write up a feature story for the paper, an offer I took up with enthusiasm.

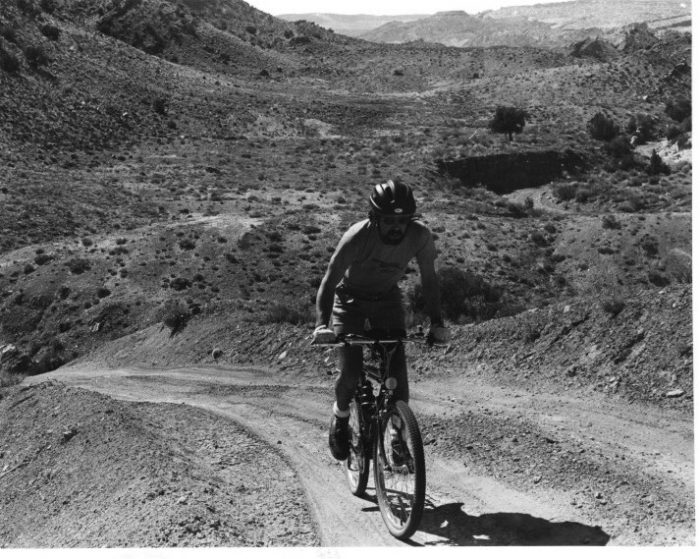

As neither one of us had ridden in a few years, we decided to start out with an easy, fairly short ride, driving the bikes down the Egg Ranch road onto the dirt in the valley below Hurrah Pass (which, for some reason, we have always pronounced “Hoo-rah”), then riding to the top and back down to the car. It was an epiphany, a revelation, and some of the most fun I had ever had on two wheels.

You really could ride those things anywhere, the knobby tires soaking up impacts and providing traction in dirt and sand. The oversized brakes gave lots of confidence in steep downhill descents, and the off-road handling was quick and responsive, the traction on slickrock amazing.

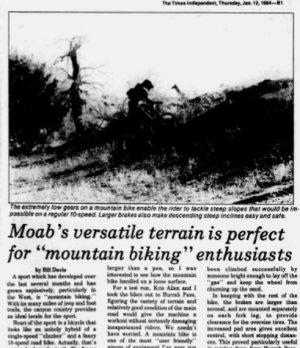

I wrote a “gee whiz”-type article for the Jan. 12, 1984 edition of The T-I on how swell the area would be for the new sport. I believe it was one of the first articles about mountain bikes ever printed. Mountain Bike Magazine out of Crested Butte, Colo., debuted at about the same time, but I don’t know who was first. Small groups of bikers were exploring the new technology in Marin, Calif., and Crested Butte at the time.

Following the test ride, both Kris and I decided we had to have one of the new bikes immediately, and dipped into our college savings to purchase the number-three and -four mountain bikes sold by Rim, according to the Groffs. I don’t know who bought numbers one and two.

Between January and our departure to Logan in September, we rode every chance we got everywhere we could, and, I must ask you to imagine, given what followed, we never saw another mountain bike or rider anywhere. Riding alone in all that beautiful country was a unique privilege.

We mostly stuck to Jeep trails, some of which we had explored previously in my ’69 CJ5, including Salt Valley and Eye of the Whale trails in Arches. I even took a shot at the Moab Rim Trail, but decided that was a one-off, as hiking allowed you to actually look at the scenery without risking death.

Somewhere along the line, someone (probably Bill or Robin) mentioned the Slickrock Bike Trail off the Sand Flats Road. The trail and its practice loop were originally developed for motorcycles by the BLM around 1969. The trail, which was marked out with painted arrows on the rock, featured a variety of terrain, ranging from short sections of sand to long stretches of steep slickrock.

The trail skirted the upper reaches of what was then called Negro Bill Canyon—with spectacular views of the canyon floor, Moab Valley, and the LaSal Mountains.

We rode there frequently, and again, never saw any bikers, motorized or not, with the exception of one motorcycle on the practice loop, once.

I hear tell that situation has changed.

So the comparison and contrast were there: The local economy was collapsing, not for the first time, in Moab’s boom and bust cycle, but at least one family had created a new business that was destined to thrive, as many others were downsizing or closing their doors forever.

In the years since, the economic pendulum has continued to swing from one extreme to the other. Since I had first started poking around Southeastern Utah in 1968, I wondered if Moab would ever be “discovered.” I had always hoped the community’s isolation, rugged terrain, and harsh climate might protect it. That obviously hasn’t worked out. Moab has been Aspenized, just like Jackson Hole, Crested Butte, and Montana (the pretty part, at any rate).

I have seen uncontrolled growth before—repeatedly. I grew up in the biggest-ever example, Southern California in the immediate postwar period, the 1950s. In Santa Barbara, where I was raised, it was normal to see the city push outward on its boundaries by a mile or more each year. Places where my sister and I hiked behind our modest, isolated house became massive housing developments in a matter of a couple of years.

Southeast Denver, where I lived for a spell after graduating from college, underwent massive growth in the early 70s, when John Denver became Colorado’s largest industry, outstripping Coors Beer.

During 24 years teaching in Stockton, Calif. in the Central Valley (College teaching jobs are rare; you have to go where the work is.), the community grew several miles west, into San Joaquin River marshlands and agricultural fields adjacent to our apartment, where Kris and I used to walk after work.

During that same period, the carrying capacity of Southern California had obviously exceeded workable bounds. Once a year, I used to attend a journalism faculty conference in Morro Bay, on the coast near San Luis Obispo about 200 miles north of L.A. My colleagues from the Southland frequently commented if they didn’t leave Los Angeles by 3 a.m., traffic would be so bad the trip north wasn’t worth the effort, as they wouldn’t arrive by early evening, when the meetings began.

Reno, from whence we moved a few months ago, is also growing explosively, advancing by miles each year in a fashion similar to California. Sagebrush hills where we walked the dogs have disappeared under warehouses and housing projects.

The return to Utah has been a bit of a shock. I remember when the drive north from Salt Lake to Brigham City along the mountains featured horse farms and orchards with roadside fruit stands. It is now built up, with all the same chain stores you see from coast to coast, and massive housing developments. Draper is looking an awful lot like California, as well.

When I arrived in 1978, Arches visitation totaled 326,948. In 2019, pre-Covid, the total was 1,659,702. That’s scary (To generate a collective sigh among my readers, the 1929 total at the then-monument was 500. For the year.)

What is even more alarming is the type of visitor. When I first returned to town and was camping at Devil’s Garden, I climbed onto a sandstone fin, looked north toward the Book Cliffs (and I-70, I must admit) and reflected that nothing had changed since the last time I stayed there in ’68. I was profoundly grateful.

During later explorations while I was at The Times, on foot, in the Jeep, and finally, on mountain bikes, Kris and I had the same attitude toward the terrain:

“The land is beyond beautiful, we love the quiet, and it’s our responsibility to keep it that way.”

That included knowing the history of the area, both natural and human, respecting it, and leaving the land as we found it.

Whatever transportation we used, it was just a tool to get farther out in the sticks. I was never one of those “bet I can make it up that cliff” types, holding to the old adage “Four-wheel-drive gets you to a much worse place to get stuck.”

Judging by photos and videos, Grand County has been invaded by people who don’t adhere to any of the above beliefs. And their sports…Henceforth, let them be known as “Hold My Beer and Watch This” activities, “HMBAWT” for short (pronounced “hymn-bought”).

In HMBAWT, the landscape is used only as a backdrop for an activity; the place is not the goal. Bikers, both pedal and powered, could race over heaps of garbage, if they could figure out a way to pile it high enough for the jumps, and it wouldn’t make much difference. Rock climbers have proven their sport can be exciting on the side of a building, or indoors. Certainly, it can be done without bolting a route over native rock art (Who uses bolts nowadays anyway? Those went out of fashion when I was climbing in the 60s, an era when climbers were transitioning from pitons to cams, maintaining a rigid esthetic of leaving the rock unmarked and pristine as possible).

I suspect this “landscape as background for my fun” attitude also breeds such obscenities as the recent vandalism of ancient pictographs and petroglyphs. Why, for the sake of everything holy, can you not just leave it alone? The Canyon Country is not a theme park, put in place for you to party.

A major part of the problem is simply, or not so simply, too many people. So what’s the solution? I have no bloody idea. My job at the moment is to wax nostalgic and entertain my readers.

Answers, if any, will have to come from those most directly affected—the current residents—with support from those of us who still love the place—even if from a distance. I’m not likely to return soon. When I drove the rental truck up Moab Canyon in 1984, I caught a glimpse of the valley behind in the driver’s side mirror, framed by the sandstone walls, and as my vision blurred, had to pull over near the top for a solid cry. It broke my heart to leave, and I’m not ready to break it again coming back. Not yet, anyway.

I dislike crowds—always have. I believe that as the size of a group grows, the I.Q. of the individuals within the mob drops proportionately, frequently resulting in mischief. I like people just fine, but prefer my humanity in limited doses. Moab, at the time, was a perfect fit; empty was its specialty. Conversely, I’ve never lived in a place where I had more friends. Comparison and Contrast.

Afterword: Robin Groff died Jan. 2, 2019, way before his time. The bike park for beginning riders in his name is a great idea. Requiescat in pace.

Afterword, the second: If it hasn’t already been done, something similar might be considered for the memory of Doug Farnsworth, who likely saved lives, possibly including mine, during the Doxol fire which I wrote about in the past issue—perhaps a shaded pullout along the highway at the north end of town. A plaque could list his name and those of the other victims, along with a description of the fire.

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Amazing how far mountain bikes have progessed. Around Stockton there was many roads (in the islands), perfect for road bike trips (few cars but dogs were a problems).

Came through Moab a few times in those years, first was around 1983 while a friend was helping me move to Durango to get my geology degree. It was a strange trip across the desert, somewhat common in those years, so I don’t really trust my memories of the town. The next trip I definitely remember, it was a geology field trip in about 1985, the town was blasted and disheveled, other than some giant place on a hill built by some uranium king, and that neat bike shop that had mountain bikes, that were sweeping Durango at the time. Both towns are now unrecognizable, my condolences to those who really lived in Moab during those years, cherished memories I’m sure.

Thank you for this remembrance Bill, I share your view of HMBAWTS and Crowd Theory. Moab & CANY were pivotal in my transition from oil field tramp to tree-hugging cryptogam worshipper in the late 70s-80s. It became a regular layover in my annual migration from Idaho mts. to canyon country, to SW CO, rinse, repeat for years. The folks down at Needles, particularly Thea N., made a huge impression, and my long time best friend (Mr. D. to Moab high schoolers) still lives there, the reason I still visit whenever possible. Moab was as fine a place as you could hope to meet. Miss those milkshakes & chilicheeseburgers at Milt’s & risk-free jaywalking. In ’81, after a winter stint in Needles, I had a life-changing bicycle mishap and thanks to the kindness & care of the folks there, I recovered phenomenally fast. A couple years later, wanting to ride a mt. bike to AK, and not finding one within 100 miles of the Idaho ranch I called home, I wrote Ross Bikes in Allentown PA to ask how I could get one. They said buy 3 at wholesale and you can have the dealership for your area. So I outfitted all my friends and family with wholesale Ross bikes, and went to AK in ’84. But I never got into riding for entertainment, did Slickrock once, not for me. I’ve always seen bikes as a means to travel on a shoestring, and fully experience the trip’s sights, sounds, & smells.