I was an engineering student at UC Berkeley in the early 1960s. The student body was much smaller and campus quieter before free speech and Vietnam came along. There was no admission charge for California residents, just a $150 admin fee per semester before Ronald Reagan became Governor of California and decided students could afford to pay tuition if we had the time to take to the streets and protest our lack of free speech or a Vietnam war.

I had heard of Phil Pennington, a graduate student in the UC Mining School, next door to the Engineering School who was always leading nature trips to faraway places in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and beyond.

The UC Hiking Club was a fun place to meet people who love the outdoors as I did and Phil was really an evangelist for exploring the lesser known or unknown places, whenever there was a study break or vacation. God, I remember our climb of Mt. Shasta in the midwinter break that first year, 14,532 feet high, the second-highest peak in California. It took three days with snowshoes, then crampons and ice picks to climb the 45-degree slope of Avalanche Gulch to reach its top.

And now Phil was preaching another tempting exploration, a remote canyon that very few knew about on the Colorado River in Utah. It was about to disappear behind a dam in 1963, so he was organizing trips to photograph and memorialize it before it was submerged under a large reservoir that became Lake Powell. We were mostly UC Berkeley students that had signed on wanting to see and explore new environments, and maybe help to save them.

It was an all-night drive from Berkeley just to arrive at the end of the paved road in the small town of Escalante, Utah, where we transferred into jeeps to reach the river at a place called Hole in the Rock, so named by the Mormons who blasted a passage in the canyon wall at that point to cross the Colorado and settle more of Utah in the 1800s.

This was the Glen Canyon later made famous by The Place No One Knew, a Sierra Club book and film. Eliot Porter was the photographer and filmmaker who gave public recognition to this canyon the Colorado River had carved into magnificent formations north of the Grand Canyon. But it didn’t have the spectacular views of the Grand Canyon 100 miles to the south, though its sheer cliffs soared as high as 2,000 feet and been inhabited by native-Americans since at least 1,000 AD. We learned much of its history from archeologists we encountered along the way who were preserving what they could from the ancient cliffside ruins.

I remember we bounced across the Kaiparowits Plateau with our equipment—either kayaks, or inflatable rafts, and even a German-made Fold Boat to take us down approximately 100 miles of the Colorado to the brand-new Page Dam that was beginning to form Lake Powell.

The first trip during UC’s Christmas break was the most unforgettable. By the time dawn was breaking over the eastern sky we were exhausted from the all night ride after another 62 miles of sand track from Escalante. That’s what wilderness can do in taking one out of usual experiences and a sleepless night.

Suddenly, a line of crucified bodies on high poles with their hair waving in a slight breeze appeared in the eastern dawn sky along the dirt road we were traveling.

That stopped us in our tracks. What were we looking at? Bleary-eyed from the drive, none had the slightest idea. Spartacus had just been released, which portrayed the conquered rebel slaves crucified on crosses in a line that stretched to the horizon, but it was another matter to see such a line right in front of me rather than on a movie screen. It took some time before we saw they were not real bodies despite the waving hair from a slight breeze, but a incredibly realistic rendition of crucifixions strung out on evenly spaced poles for at least one-quarter of a mile.

Then we came upon the walls of a towering, castle-like façade which had to be the front of a walled city with another crucified figure on a cross leaning against the wall with a tin can in hand, as if for donations. I can remember the eerie feeling of what was beginning to look like a movie set in the most-out-of-the-way place imaginable. It could be of an ancient world, or the future world of science-fiction. We next encountered a small, deserted, white-domed village before descending to the shore of the Colorado River where several pine trees upon close examination sat silently on their artificial bases. We now knew this had to be a movie set, but for which movie?

And what was this doing in the middle of a pristine wilderness, accessible only by jeeps or four-wheelers? We were mostly disappointed that it no longer seemed so pristine, in a word.

It was also mid-winter. The weather has suddenly turned extremely cold over the Christmas holidays with snow on the ground and ice floes floating by us in the Colorado River. I hadn’t anticipated this, having just a one-person inflatable raft on our first trip that was continually punctured by the sharp-edged floes as we began paddling down the river. So I had to come to shore to patch it with every puncture. On one such break a couple of cowboys on horseback watching our tribulations rode over to talk. They said they were movie wranglers tending stock; horses, goats and sheep that had been penned further up in the canyon rocks.

It turned out we had come upon the set of The Greatest Story Ever Told, George Stevens’ epic of Christ with Max Von Sydow as Christ, and Charleston Heston as John the Baptist. But they had stopped filming for a couple of weeks because it had snowed. Director Stevens did not want snow in Bethlehem, they said, which was the white-domed village encountered, or on the banks of the Colorado, a substitute for the Jordan River where John the Baptist baptized Christ. And that was just the beginning of our journey.

It was obvious Director Stevens wanted to tell the “Greatest Story Ever Told” in one of nature’s greatest settings that most Americans would never be able to visit in person. This area of Utah and Colorado is a magnificent tapestry of mountains that loom over hollowed out canyons containing wilderness areas such as Canyonlands National Park and Arches National Monument. The Arches contain more than 2,000 sandstone arches that span hundreds of feet. Another wilderness area, Dinosaur National Monument, named after the more than 800 paleontological sites containing dozens of dinosaur species on the Green and Yampa Rivers that run into the Colorado above Glen Canyon.

The cowboys told us many stories as we huddled together. It was dawn and freezing cold. So they would kick in one mesquite bush after another and light them, which we huddled around to keep warm. They had been stock wranglers for many other movies, they said, such as The Soldiers Three with Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra and led trips for movie stars such as Clark Gable, who hunted cougars that roamed the Kaiparowits Plateau during those times and were considered predators to be eliminated by the ranchers.

This was an example of what most Americans would never see in person—except in movies such as George Stevens’ epic The Greatest Story Ever Told.

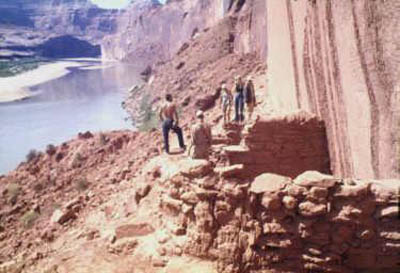

The unreality of a biblical movie set reinforced our resolve to preserve as much of the real canyon as we could with pictures. Glen Canyon had brilliant, multi-colored cliffs and hollowed out sandstone formations that led into tributaries and labyrinths too numerous to count, and the plateau that loomed above it. It was also home to the Moqui and Anasazi Indians that lived in cliff dwellings centuries earlier, impossibly perched in almost inaccessible caverns and ledges high up the walls of the canyon.

Their ancient dwellings were tucked into pockets that were accessible only by very narrow footpaths in some places to protect them from marauders; some walls so sheer that ladders were needed to access them. All this was being inundated by Lake Powell, named for John Wesley Powell, a one-armed American Civil War veteran who in 1869 was the first non-native American to lead a party that traversed the Colorado River in three wooden boats.

By the second trip in February 1963, the word was out. The Page Dam had closed, and its reservoir began to fill as we approached it. Now all manner of preservationists; including anthropologists, botanists, and archeologists were clambering over cliffs photographing and collecting what artifacts they could find as we floated down the rising river that no longer had ice floes, among beavers and other wildlife looking for new homes. We also saw Navajo sheepherders with their sheep on the eastern side of the river which bordered the Navajo Reservation.

Glen Canyon had no difficult rapids and mile-high cliffs compared to the Grand Canyon, so it wasn’t spared a dam to power the lights and air conditioning of Arizonans. The Colorado River would fill Lake Powell; therefore becoming accessible to all with motor homes and motor boats to roar up and down its length in what became the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

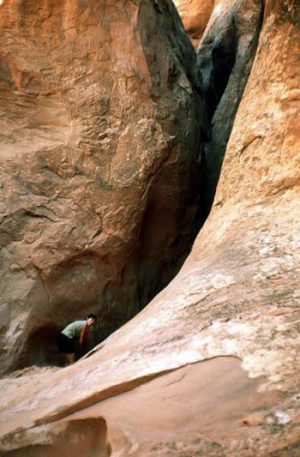

We were seeing a rare and beautiful canyon being inundated to create a recreational lake for the many and provide more electricity for a growing Arizona. I still remember the side canyons in shades of orange and purple, such as Labyrinth Canyon where the sun barely penetrated. It narrowed to two feet in places; just wide enough to squeeze through. And Cathedral in the Desert with its soaring spires on walls that arched overhead to create a sacred place. Under the bluest of skies, we were surrounded by a silence broken only by the rippling, flowing sound of a placid stretch of the Colorado River.

In January 2003, forty years after Page Dam closed, David Brower, former Executive Director of the Sierra Club wrote in the Sierra Club Magazine that he regretted the Sierra Club’s decision to agree to the Page Dam project, because it turned out to be an unnecessary dam. It was one of many dams built at the time that lost their reason for being.

He had thought at the time that it would be a way to prevent more dams being built on the Colorado and help to preserve the Grand Canyon, as well as serve as a basin to slow down the silting of Hoover Dam’s Lake Mead further downstream. Most of the Grand Canyon is made up of sandstone formations that erode into the river during spring melts transporting enormous amounts of silt.

Why did Page Dam turn out to be unnecessary? Studies Brower cited maintained it robbed water from Lake Mead and Hoover Dam that actually reduced its amount of generated power. “Except for a minor diversion at Page, Arizona, and the 30,000 acre-feet delivered annually to the nearby coal-fired power plant, all the water not lost to evaporation or leaks is diverted to users downstream at Lake Mead and below,” said Brower in the Sierra Club article. “Lake Mead’s Hoover Dam can control the Colorado River without Lake Powell and can produce more power if Powell’s water is stored behind it saving massive amounts of money, water, and wild habitat. Economics and ecology are ready to team up on this one.”

“Glen Canyon died, and I was partly responsible for its needless death,” wrote Brower in The Place No One Knew, Eliot Porter’s Sierra Club book first published in 1963. “Neither you nor I, nor anyone else, knew it well enough to insist that at all costs it should endure. When we began to find out it was too late.”

The Glen Canyon Institute was formed in 1996 to advocate restoration of Glen Canyon. It is also part of a growing river restoration movement to remove other unnecessary dams that is gaining increasing popularity with the public. More than 460 dams have been removed in the past 40 years in the U.S. at this writing.

It says on its website, www.glencanyon.org, “At the heart of the River Restoration Movement is Glen Canyon Dam and the movement to restore a healthy Colorado River. The loss of Glen Canyon was a turning point in the birth of the modern Environmental Movement and has been mourned since the dam’s construction. As the symbolic heart of the movement today, the movement to restore Glen Canyon represents our society’s realization of the value of free-flowing rivers and complex ecosystems that depend upon them. Glen Canyon, which was hailed by many as one of the most beautiful places on earth, was lost to the thoughtless era of dam building.”

That was why Glen Canyon became The Place No One Knew that I and a few others were privileged to see for maybe the last time in its pristine form. There was something about those trips, and the Berkeley activists such as Phil Pennington, an early environmentalist that inspired many of us to want to protect our environment.

“Whatever the final details of Lake Powell’s water losses turn out to be, the draining of the lake simply has to happen,” wrote Brower. “The river and the regions dependent upon it, including Baja California and the Gulf of California, can no longer afford the unconscionable loss of water. We need to get rid immediately of the illusion that the only way to protect water rights is by wasting water in Lake Powell. We can simply let the flow reach Lee’s Ferry, Arizona (the dividing point between the Upper and Lower basins), naturally, beautifully, and powered by gravity at no cost.”

There is no more important fight to save our planet from the further loss of such beautiful and inspiring places as Glen Canyon. And efforts by The Sierra Club and others are now in motion to restore it, if the U.S. Reclamation Bureau can be convinced that it is no longer necessary. The tide has turned on the need for more hydroelectric power; as alternative forms of energy such as wind and solar power replace ecologically damaging hydroelectric projects.

David Brower gives credit to other conservation organizations that support restoration of Glen Canyon, such as the National Parks Association, the National Wildlife Federation, and The Izaak Walton League, but it will take decades to restore Glen Canyon even after Lake Powell is drained. And today The Glen Canyon Institute has been formed that is “Dedicated to the restoration of Glen Canyon and a free-flowing Colorado River.”

I even dare to say that these experiences outside of a classroom were as educationally enriching as a formal education at UC Berkeley, or any institution, and open to those curious about and wanting to explore the incredible variety of life that surrounds us.

I later joined the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the year the EPA was formed to protect as much as we could of our environment. This was in large part because of my initial, unforgettable experience in The Place No One Knew. And participating in the effort to preserve and maybe restore it is our contribution to preserving what we can of nature’s beauty, which is truly The Greatest Story Ever Told.

Harlan Green lives in Santa Barbara, CA. He is a banker and Mortgage Broker, with degrees in Economics from UC Berkeley and Film/Broadcasting from Boston University. He has written financial columns and articles for west coast newspapers and periodicals, and conducted financial seminars for more than 20 years.

For more on the filming of The Greatest Story Ever Told, read Tony Van Renterghem’s LAST DAYS of GLEN CANYON & ‘The Greatest Story Ever Told’ from the Zephyr Archives…

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Interesting and informative story! Of course a couple of things have occurred that may change the arc of this story: (1) the Navajo Generating Station is (or will soon be) decommissioned, so the water it needed from Lake Powell will no longer be needed, and (2) the prolonged drought is lowering water levels so much that it’s only a matter of time before the hydroelectric turbines in the powerhouse won’t have enough water pressure to generate enough power to make them worth keeping in operation. I wonder, though: If the lake is indeed ever drained and the dam decommissioned, will the dam be dismantled?

It’s hard for many to comprehend, but the draining of Lake Powell is an elitist project. When the lake goes back to being a canyon, the people who have been able to recreate there and enjoy that beautiful landscape with their families will be left with the kind of access they have in the Grand Canyon. They’ll only be able to peer down into the hole, snap a few pictures, then head for the gift shop.

I feel grateful that my family was able to bring my grandparents to the lake for so many years. To float, to swim, to camp, to watch the kids ski, and to sit out under the stars. The environmentalists’ worldview presupposes that only those who can hike all day should have access to nature’s beauty and to the health benefits that spending time in nature provides.

In addition, this is being done in spite of the wishes of the people who live in the region. Lake Powell was turned into a national recreation area with a name that advertises to one and all its intentions: it has already been renamed Glen Canyon. As they did with all of the wilderness areas of the Utah desert, the controlling agencies in conjunction with environmental lobby groups will host some public meetings and let the citizens who live nearby voice their opinions, but those opinions won’t be taken into any account. Representational government ceases to exist if you’re a dumb hick. They will pretend to seek public comment, then they’ll do what they had planned to do anyway.

The draining of Lake Powell will be another tragedy of the collapse of fair and representational government, and of fair access to public lands. It will, once again, benefit the outdoor recreational gear industry – Patagonia, REI – and be another force that limits average and elderly Americans to scenic drives and overlooks. But at least they’ll be able to say they got the T-shirt.