The first time I picked up a cigarette, I was probably six years old.

It was late morning, mid-summer, and the babysitter had let us kids out into the park next to her home while she returned inside to begin preparing lunch. I didn’t stay in the park, of course. I didn’t like to stay where I was told to stay. I crossed the quiet street with a little blond boy. We stood in the parking lot of a small apartment building, found some cigarette butts littered around the pavement, and began to pick them up and smoke.

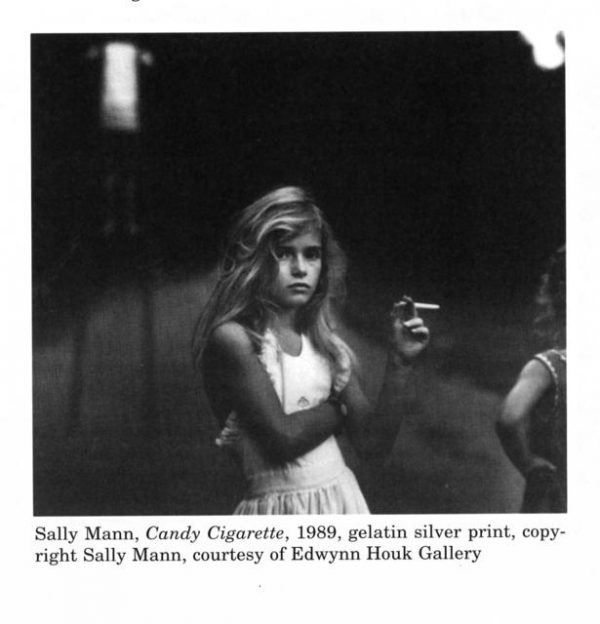

Or so we called it. We didn’t have any matches, only imagination. I held a mangled butt to my mouth, pretending a deep inhalation. Then, dropping my hand to one side, I closed my eyes and exhaled in visible relief. The little boy, leaned against the rear bumper of a pickup truck, did the same. “I gotta quit,” he said. I nodded. “These things are killing me, I know it.” We each took another long, world-weary drag and looked up at the sky.

Sturgis, South Dakota was that kind of town. In my friends’ houses, the adults all took the same long, slow drags on their cigarettes. They closed their eyes, leaned forward over the kitchen table, and exhaled with a long sigh. They’d eye us kids. “You don’t ever start smoking these things,” one mother said, staring us down where we sat on the carpeted floor. “They’ll kill you.” She took another drag and closed her eyes. Her shift would start at the bar in a half hour, and she had her purse next to her on the table. Her daughter and I nodded soberly, agreeing.

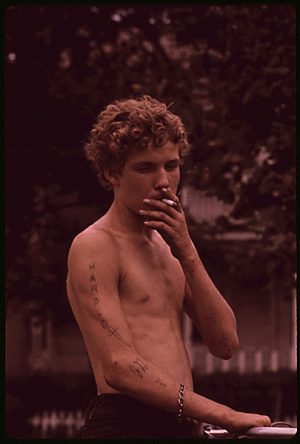

A decade later, in my late teens, I smoked my first real cigarette, a Marlboro Red. I was standing on a hotel balcony in Athens, Greece. I was looking out over a dimly lit side street in the heart of the city. I smoked self-consciously, with slow movements, not wanting to look like an amateur. I leaned against the railing and looked down at the men lingering beside the corner newsstand.

The newsstands in Athens sold alcohol and tobacco as well as tabloid magazines and daily broadsheets. I discovered they sold these things to anyone. Even teen-aged Americans. Men gathered around the stands all day, sometimes long into the night, to talk and jostle each other. Below me, by the stand, the men were joking around. They turned occasionally to yell down the street, where an impromptu soccer game had erupted in a field beneath a stand of plane trees. Even from this distance, I could hear the cries of the game. All along the sidewalk, men were leaned back against the buildings. Some were sipping listlessly at their drinks. Others were just smoking their cigarettes, glancing occasionally toward the ruckus down the block, and then relaxing against the stone walls.

A few stories above them, I took another drag off the Marlboro. I was a long way from home, and didn’t speak the language. It had been a hot day. But now the evening was cooling off, and with my cigarette, listening to the sounds of the game down the street, I felt, just briefly, a part of the scene. Not a foreigner anymore.

Loving (and Losing) My Cloves…

I never became a true smoker. I don’t have the wiring for addiction. As I got older, I just bummed occasional cigarettes off whoever was around. And one night, I got lucky. The “whoever” standing next to me was carrying a pack of Djarum Black cloves. I took one drag off the black paper, and was hit with a powerful sensation of memory. These Indonesian spiced cigarettes tasted like a place—or the way a place feels when your true memory is overlaid by the fog of telling and re-telling yourself what it felt like. Sweeter and more whole than the real place. They smelled to me like that night in Greece. Like diesel smoke and the aroma of the restaurant kitchens closing up for the night, honeyed pastries and grimy streets with stale Ouzo drying on the pavement. Steaming hookah pipes on the little tables outside the tea shops. That’s a lot to put into a cigarette, I realize. But that’s how it felt.

As soon as I found a tobacco shop that carried them, I bought myself a pack. I still wasn’t a smoker. But now, on the nights when I needed a break, I could stand outside and puff on one for a while, feeling like I was moving through time and across oceans. It’s a powerful balm, when you’re facing down final exams. It took the edge off.

For years, I always had a pack of Djarum Black in my purse. Occasionally, when I couldn’t get the Blacks, I’d pick up a regular pack of Djarum. Those weren’t bad either. But reliably, when I needed to have a quiet calm moment, I could stand outside and watch the flicker of paper lighting, and smell that same heavy spiced smell, and feel a little better.

Then, in the summer of 2009, I handed a cigarette to a guy outside the bar where I worked. “Oh man,” he said, looking down at the black cigarette in his hand. “A clove. I love these. You know they’re getting banned?”

No, I didn’t know.

He looked down at the cigarette sadly. “It’s this stupid law they’re passing.”

I looked at it too, thinking, maybe I shouldn’t be loaning these out anymore.

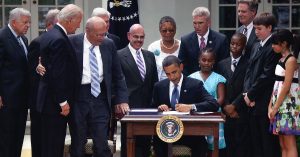

I soon learned that, in order “to protect the public and create a healthier future for all Americans,” the federal government was going to take away my clove cigarettes. The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act banned all “characterizing” flavors in cigarettes, save for menthol. It also banned the sale of cigarettes in any amount other than the regulated 20-pack, required larger warnings on the packs and banned tobacco sponsorship for sporting games. It banned cigarette vending machines in most places. Certainly there were other things in the bill too, but I didn’t care too much about the other 83-plus pages of the Act.

I spent the entire second half of that year—from June 22 until December—discussing with other Djarum devotees whether the government would really take away our cigarettes. It just didn’t seem possible. We were adults. We were doing something legal, and our smokes weren’t any more dangerous than the Camels and Newports and American Spirits our friends were carrying. Were we being punished for having better taste? This was supposed to be America, after all. Land of the sedentary and addicted. Of all people, why go after us?

I still remember my last clove purchase. In March of 2010, I was in a small grocery/convenience store in Bodega Bay, California when I spotted two packs of Djarum Black on the shelf behind the counter. I bought them on the spot. “Do you have more?” I asked the clerk.

He looked at me like I was crazy. “No,” he said. He put the packs down in front of me.

“They’ve stopped importing them,” I explained. “I haven’t seen a pack anywhere since December.”

He handed me my bag of snacks. “Uh-huh,” he said. “Do you need a receipt?” Clearly he found the topic riveting. I thanked him and left the store, one hand resting protectively on my purse, which now held those two precious packs of cloves.

Those were the last Djarums I saw in the wild.

For Our Own Good…

The explanation proferred by the government for the ban was the same explanation always given to take something away from self-governing adults: kids might like it too. Any cigarette that tasted better than pure tobacco was a ploy to draw more kids into smoking. Cloves tasted better than regular cigarettes. Ergo…

Now, I was pretty sure it was already illegal to sell smokes to kids, regardless of the flavor. And the idea that “if it tastes good, it must have been designed for children” seemed to me to overestimate the average adult’s palate for the unpalatable. Adults like things that taste good, smell good, look good, just as much as kids do. More, in fact, since we have the income and the intelligence to really hone our tastes. What kid cares whether his cigarette tastes like Asian spices? That’s an adult peccadillo. A kid who smokes is relying on the kindness of the black market. Speaking from experience, I can tell you: those kids will smoke anything.

The 2009 law always seemed to have less to do with protecting children, and more to do with punishing adults. The ones who were supposed to know better by now. After fifty years of drastically whittling down the smoking population to a fraction of what it once was, after all the public service announcements and the warning labels and the presentations in schools, even after those terrifying anti-smoking commercials and the woman inhaling a cigarette through the hole in her throat, somehow there were still a few stubborn smokers out there. And that just drove the anti-smoking crowd crazy. They had chased the smokers out of every public building already. They were pushing them out of restaurants and bars. And yet, for some reason, those smokers didn’t quit. So now it was time to start banning the cigarettes themselves.

The 2009 law was a test. The cloves disappeared from the shelves, and nobody complained too loudly. Over the course of the next decade, smokers were vilified out of outdoor venues, and out of public parks. Their tiny “smoking areas” moved farther from the doors of buildings. Large companies and health care organizations began announcing they wouldn’t hire tobacco users. States added increasingly punitive taxes onto the sales of cigarettes, so that nationally, the poorest smokers went from paying 8% of their annual income on their habit in 2003 to 13% in 2011, and in the highest taxed areas, particularly New York State, that percentage more than doubled, to 24%. Those high taxes didn’t make poor smokers quit. They just drove them deeper into poverty. Even knowing this, the taxes in most states continued to rise.

One of the more glaring attacks on the smoking public arrived in the text of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. The bill was meant to expand health care access to America’s poor and those who most needed medical help, but it contained one caveat. While insurance companies couldn’t raise rates based on a patient’s pre-existing conditions, on their weight or sex, or even on their abuse of alcohol or drugs, they could raise rates based on tobacco use. With that one condition, the law ensured that a large swath of America’s working class would remain uninsured. And somehow, after eleven years, and the elections of hundreds of politicians who claim to speak for the underdogs of society, that loophole remains.

The smoking crowd is just too easy a target. A little under 20% of Americans use some kind of tobacco product, with 14% using cigarettes. But tobacco use is noticeably higher (26.2%) among those making under $35,000 a year. It’s high among those with a disability (24.3%), those who are uninsured (29.9%), among Native Americans (32.3%) and those in the LGBT community (29.2%). It’s very high among those who are experiencing serious psychological distress (36.7%) and among those (41.4%) whose education stopped at the GED level. The main characteristic of all these groups is that they don’t have a lot of political power. They are easy to dismiss and easy to vilify. And because many are legitimately struggling, the rules that make their lives harder can all be couched as “help”. All the punishments are created for their own good. This is a group of people who clearly can’t take care of their own interests, the thinking goes. So someone ought to do it for them. The public sentiment against them has increased to the point where a majority of smokers now feel actively discriminated against for being a smoker.

These days, on the rare occasions when I light up, I just expect to hear about it. From complete strangers. From friends. Someday I fully expect to be sitting in the woods somewhere, just quietly enjoying my clove with the trees and the grass, and no one around for a country mile, only to have a squirrel stop and glare at me.

“You know, you really shouldn’t smoke” the little jerk will say, flouncing its fluffy manicured tail.

And then it will cough theatrically. And give me that look.

A New Prohibition…

So we’ve arrived in 2021. Barely. We somehow made it through last year, and here we are. And now another smoking restriction is in the works. The FDA announced at the end of April that they plan to “issue proposed product standards” in the next year to ban menthol cigarettes (the one exception from the 2009 law) and all “characterizing” flavors in cigars.

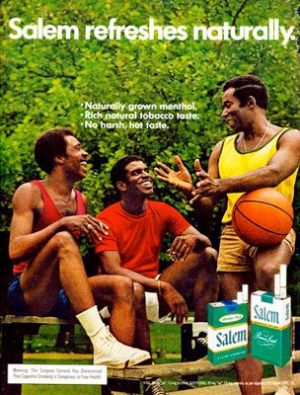

And because the FDA knows a catchy tune when it hears one, the goals of this new ban will be racial justice in addition to public health. This is from the FDA’s announcement:

“For far too long, certain populations, including African Americans, have been targeted, and disproportionately impacted by tobacco use. Despite the tremendous progress we’ve made in getting people to stop smoking over the past 55 years, that progress hasn’t been experienced by everyone equally.”

Essentially, because black people smoke menthols more commonly than white people do—and because they were often targeted by menthol advertising in the past—the continued existence of menthols is a kind of racism. Never mind that the people who smoke menthols might enjoy them and genuinely prefer them to other cigarettes. Never mind that they’d rather keep smoking them, thanks, if you don’t mind. When an anti-smoking group recently polled menthol smokers to ask them what they thought of a ban on the product, 71.5% were against it. (And honestly, it’s astonishing the anti-smoking group even thought to ask the actual smokers. It isn’t like anyone was going to listen to their opinions.) But the FDA had already decided that it serves the cause of progress to ban a product that Black Americans overwhelmingly prefer. That it should be banned, in fact, because they prefer it.

That’s how social justice works, right? You just take an activity that’s currently practiced legally by a group of people, and you suddenly and arbitrarily make it a crime punishable by law enforcement. Even if the smokers themselves aren’t a target for arrests (and the FDA says they aren’t,) anyone caught selling them will be. There shouldn’t be any issues there—no new crackdowns in poor neighborhoods, no one getting shaken down on street corners. It’d be one thing if there was some history of tension between Black Americans and the law enforcement community, but since that obviously isn’t the case…

Just last year, a study of menthol bans in Canada showed that, while banning menthol cigarettes did reduce menthol cigarette smoking in teenagers, it increased non-menthol cigarette smoking at the same rate. The amount of smoking overall remained steady. And those who didn’t want to switch from their menthols turned to a newly-created black market. It’s hard to imagine things playing out differently south of the Canadian border.

For one thing, this country already has a thriving black market in cigarettes. A 2012 study found that, in the high-tax state of New York, only 55% of all cigarettes smoked were purchased at the legal taxed rate. The other 45% were bought illegally—smuggled in from lower-taxed states and Native American Reservations, and often sold individually as “loosies” instead of by the 20-unit pack. One survey conducted in the South Bronx in 2013 suggested that roughly 80% of local smokers were accustomed to buying individual “loosie” cigarettes. The going rate was 50 cents a loosie. This was four years after the 2009 Act—my clove-banning law—made those loosie sales a federal crime.

Making Hard Lives Harder…

Every ban creates a black market. It’s a law of nature. Even my cloves are still available if you know where to look. (Not that I know where to look. Not that I have any in my possession.) The second half of the new proposed ban—eliminating “characterizing flavors” in cigars—is meant to shut down the black market in cloves that sprang up after the initial law went into effect. After 2009, Djarum just repackaged their cigarettes in slightly thicker form as cigars, and the online market for them proliferated. Because, hey, that’s what people do. We get around stupid laws. As a country, we seem to be slowly understanding the logic in reducing criminal punishments around marijuana, even mushrooms and other hallucinogenics. Not because it’s a great idea to put those substances into your body. But because there’s some wisdom in the government just letting people figure things out for themselves. And, if nothing else, the black market tends to be just as destructive to society as the substances are to the body.

To illustrate the impact of those newly-created black markets, consider the case of Eric Garner. Garner is dead, firstly, due to the illegal chokehold used by the officer arresting him in front of a beauty supply store on Bay Street in Staten Island. That chokehold is the primary cause of his death. But the chokehold isn’t the only injustice in the story. Garner was known as a regular seller of loosies. He’d been arrested roughly 30 times, mostly for crimes related to selling unlicensed cigarettes. When he broke up a fight on the street that night and saw the officers approach him, he knew why they were targeting him. He said:

“Every time you see me, you want to mess with me. I’m tired of it. It stops today… Everyone standing here will tell you I didn’t do nothing. I did not sell nothing. Because every time you see me, you want to harass me. You want to stop me [garbled] selling cigarettes. I’m minding my business, officer, I’m minding my business. Please just leave me alone. I told you the last time, please just leave me alone.”

Up until the chokehold, those cops were following the rules—they’d been told to crack down on loosie sales in Staten Island. They were tasked with trying to destroy a black market that only existed as a result of overly high taxes and overly petty laws, laws passed to criminalize behavior that didn’t harm anyone. People buy loosies because they’re too poor to afford a full pack, or else because they’re trying to quit and don’t want 20 cigarettes in their pocket to tempt them. Could someone sell a loosie to a kid? Sure. But that was already a crime. Criminalizing loosies only made life a little harder for poor people, (not that much harder, mind you, because the black market is prolific,) and particularly for poor people who are trying to quit smoking. In a more logical society, Garner wouldn’t have been harassed for selling loosies illegally because it wouldn’t have been a crime to sell loosies. In that society, he would still be alive.

The menthol ban will just be another complication, another weight to carry for smokers. It will just make life a little bit harder for a group of people who are already living hard lives. Living poor is hard. You can find a job—maybe—but that job is in one town and the apartment you can afford with your income is in another. So you commute. Commuting means more daycare for your kids. Daycare is expensive, and getting harder to find. Sometimes you have to leave the kids with your mother, but she’s getting old and her health is bad, and you can’t keep asking her all the time. But if they were left alone in the rough neighborhood around your apartment, who knows what trouble they’d get into. Crime is getting more frightening nearby. You start to think you should move—but where? Closer to your work? Away from your family? Gas prices are getting higher. So are the repair bills on your car. And when you get home at night, the kids are still riled and running around, and the apartment is a mess. You’re so exhausted, but you cook something anyway, and the kids are fighting and making noise, so you yell until they stop. Then you feel terrible, because this is the only time in the day you get to see them.

When you’ve fed the kids, cleaned up the dishes, and put the kids to bed, there’s only one little thing to look forward to. Just one thing. And it’s not the mail, with bank statements, bills, and collection notices. It’s not the apartment, which still needs cleaning. You have one luxury, and it’s the little break you can take to slip outside with a cigarette. You can take one moment in the dark. You can sit on the stoop and watch the smoke. Just one time in the entire day where it’s quiet, and you’re on your own and you can relax. Maybe it’s killing you. But the killing is slow and you feel better.

If You Can’t Make it Better, Don’t Make it Worse…

Every once in a while, some organization will actually ask smokers what would help them quit smoking. Most do want to quit—it’s always better not to be addicted to something if you can manage it. Especially something so toxic and expensive. But the “it feels better” is hard to overcome. A North Minneapolis group recently interviewed smokers and their families, and actually engaged them in detailed conversations to discuss what would help them kick their habit. The biggest thing that would help them to quit smoking, the subjects said, would be a reduction in their overall stress. If they could afford their rent, if they could find childcare. If life were just a little easier overall. Otherwise, they thought they could quit if they had people around them to help. Friends who were also quitting, or who had successfully quit, who could walk through the painful process with them. By themselves, surrounded by other smokers, it was just too hard.

So, if I were in the business of trying to reduce smoking in this country—like, for instance, if I were the FDA—I know where my focus would be. Instead of crafting new prohibitions, I’d be establishing and funding community-led support groups and therapy programs in the poorest neighborhoods, and I’d combine them with daycare services and employment placement services. That’s a logical way in which the government could actually reduce smoking. Unlike all the other attempts, those programs might actually have a chance to do some good. They wouldn’t treat adults like children. They’d enable people to make their own choices, instead of removing choices from them.

And maybe that will happen. More likely, it won’t. But if we can’t muster the resources to help smokers quit, then the kindest thing to do is to let them be. Why continue to harass them? It’s less than a fifth of the population, and they aren’t actively recruiting anymore. The remaining smokers aren’t harming anyone but themselves. Don’t we have a right to choose our poison in this country? Isn’t that why liquor stores were considered “essential” during the pandemic? Isn’t that why millions are on benzodiazepines?

In truth, life is sometimes hard for everybody. We each manage the trials of the day in our own ways. Some get enough strength from faith. And some get their kicks from sports. Some dedicate themselves to “purifying” their bodies. Some get stoned first thing in the morning and stay that way until nightfall. We’re all just getting through as best we can, and each technique for survival has its own pitfalls. Quite a few of our coping methods are self-destructive. But that’s just how it is when you’re dealing with human beings.

These efforts to completely rid our society of tobacco sometimes remind me of the worst form of evangelizing religion—salvation is at hand, poor sinners, if you just renounce all earthly temptation. True, healthy redemption is waiting for you all. Forgive the poor smokers, Lord, for they know not what they do… That lecturing, hectoring holier-than-thou tone of the anti-smoking movement is so pervasive, it bleeds out of the walls. If the FDA would only listen, I could tell them: your education campaign has succeeded. It worked! Good job. Everyone already knows that smoking is bad for you. Old people know. Little children know. The whole world knows. When we pick up a cigarette, we know what it is. So please, please, just leave us alone.

Tonya Audyn Stiles is Publisher and Managing Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

“Four out of Five Doctors recommend . . . . . ”

Ah yes, the world’s scientific genius helping to make the planet a safer place.

Just another example of big brother knows what’s best for us. Scary!

All true. Tried any heroin yet? I hear it’s available on the black market and not really addictive…

Check out Torches for Freedom. Edward Bernays + Walter Lipmam = where we are today.

“Lookin’ over West Virginia

Smoking Spirits on the roof

She asked ain’t anybody told ya

That them things are bad for you

I said many folks have warned me

There’s been several people try

But up till now, there ain’t been nothing

That I couldn’t leave behind”

-Lyric from ‘Feathered Indians by Tyler Childers

I’ve been smoking 52 years. That’s a lot of money. A lot of wasted health and physical damage. It’s also been a lot of relaxation during stressful and painful times. I am clearly wired for addiction. Quitting has always gotten past me. Booze and assorted drugs I can leave behind, but smoking I never have been able to beat. I’ve been trying to beat it again lately as my lung capacity is shrinking considerably as I age. I had a lung and heart screening recently and I was clear of cancer and the heart is functioning properly. I was thankful of course but also full of wonder. I didn’t think I’d last this long. I hope that it won’t be an issue in coming generations. As far as society goes, they will just find other things to bitch about in other people. Rail against the Karens. Push back against the regulators and the woke. Great and timely article.

Somehow we went from a nation founded on Mind Your Own Business to a nation dedicated to minding everyone’s business.

In part, I believe that’s because there are more of us, and we encounter more people every minute we are out in public. And we are more affluent and more educated, both factors that encourage us to think we know what is best for others.

But there also had to be an ethical change, an invasive hybrid of nanny tendencies and expansive government that somehow convinced people to surrender autonomy, in the name of the public good.

Good that is, unless you think for yourself and disagree with policy.

Great piece.

Here’s the thing: we all pay for the health problems chronic smokers typically experience later in life. It’s reflected in our insurance premiums. While a relatively small percentage of the population continue to smoke, they place a disproportionate financial burden on the rest of the population.

Your insurance premiums are subsidizing alcoholics, the overweight, pill poppers, motorcycle enthusiasts, pot smokers, construction workers and heavy machinery operators–all of whom are likely to rack up disproportionately high costs. You’re subsidizing women, some of whom may be having more babies than you would prefer, and the homeless, and all the hypochondriacs who want full body scans on a regular basis. Why do the smokers, in their dwindling numbers, bother you more than the others? Smokers, unlike everyone else, are bearing the cost of their care with up to 1000% surcharges on their insurance premiums. If anything, they’re subsidizing everyone else.

The thing is, unless you’re going to insist on absolute bodily purity from every citizen of this country–and I’ll be leaving, by the way, if that ever happens–you have to accept that some people will require more medical care than others. Those people may be smokers or opioid addicts or grossly obese. They may just be unlucky. That’s how it goes. If you’re healthy, be grateful.

–TS

Tonya, what James suggests is at least partially true, when insurance premiums are not allowed to vary because of “fairness”. It will be even more true if we get a national health plan. And that will really motivate the nannies, and their self-assumed mandate to manage others (see my comment above).

When I was in college, I was giving a lift to a friend and on the way back to the dorm he proceeded to light up a cigarette. I asked him not to; he continued to light it; I pulled over to the curb and told him to put it out or get out; he put it out with an angry huff and we never spoke again–good riddance. When I was working as an inspector at JFK, I was sitting at the end of a row of several empty chairs waiting to be assigned to board a plane. Another inspector sat down next to me, lit a cigarette, and held it such that the smoke rose in my face while he started to read a newspaper. I asked him to please move to another chair to smoke, whereupon he took a big puff and blew it in my face (assault and battery as far as I’m concerned). I snatched the cigarette from his hand and threw it on the floor; he rose to fight; then the supervisor intervened and made him sit at the other end of the row. Also, I have picked up enough cigarette butts left on my own property and in wild areas–including those that were uncrushed and burned themselves out–to see that many smokers are thoughtless and inconsiderate slobs. Cigarettes start a lot of wildfires, and the filter butts harm wildlife. Though I don’t think the government should ban cigarette sales to adults or prohibit them from smoking in their own space (thus we agree here) and would have no problem with smokers if they put their butts in their pockets and didn’t impose their habit on others, I have NO sympathy for smokers who complain about how their “rights” are being violated by smoking bans. Smoking is not a right.

tonya! i had no idea! well … a bit of insight into my present (it took years of dedicated practice to get to this) health/intake/diet situation: i went to my GP for an annual physical a couple years back, and when we met to discuss my “health” he looked at the “blood numbers” and acted somewhat surprised. “for someone whose diet seems to consist mostly of alcohol, caffeine, tobacco, chocolate and cannabis, these numbers are really good!” i DO ingest “regular food” also, but when out on my (almost) daily run or bike-ride, breathing heavily, heart-rate poundin’ away, it’s ’cause i am off-setting (so to speak) the excesses of the day before, and when the run/ride is over, my lungs and body are all the more ready(?) and looking forward to the yin-or-yang sighed of whatever anti-yin-or-un-yang i had just accomplished. whew …