This piece is excerpted from from Cold Case Chronicles: Mysteries, Murders & the Missing by Silvia Pettem (©2021). The book is available on Amazon at this link.

For a few months in 2009, twenty-first-century forensics seemed to resolve the mystery of the whereabouts of Everett Ruess, missing since November 1934. At the time, the twenty-year-old, accomplished artist from Los Angeles, California, walked away from south-central Utah with food for two months, painting supplies, and his two burros, Chocolatero and Cockleburrs. Many decades later came news of the rediscovery of human skeletal remains that, in 2009, were believed to be his. DNA was extracted, theories were pared down to fit the circumstances, and healing began for a second generation of Ruess family members as well as the young man’s large and almost cultlike following. Everett’s wandering soul was on its way home. Or was it?

The tables quickly turned as DNA profiles were compared again. And then a third comparison disproved the first two findings. Everett was Caucasian, but the remains were determined to be Native American and clearly belonged to someone else. In the intervening years, Everett’s family, as well as new generations in the news media, clung to every clue. Had Everett not vanished in Utah, he likely would have enjoyed a long and distinguished career as an artist and writer. Instead, he became a folk hero. He holds a fascination today because fellow travelers and even armchair adventurers can relate to him. His life was wrapped in an enigma as he followed, and then kept, his dream.

So begins Chapter 4 in my latest book, Cold Case Chronicles: Mysteries, Murders & the Missing, recently released by Lyons Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield. The book tells the stories of victims –– some missing, some murdered and some with changed identities. All are true, and each are mysterious in their own ways. The cases in this nonfiction narrative date from 1910 through the 1950s and include evolutions in forensics, as well as historical context in order to view the men, women and children through the lens of time.

Included are recent theories on the cases of Judge Joseph Crater (missing from New York City in 1930) and film director William Desmond Taylor (shot in Hollywood in 1922). Other chapters help to unravel the mystique of individuals with changed identities. Included, too, is a case of aerial sabotage, the “Boy in the Box,” and unusual disappearances of young women, along with child abductions and four missing adventurers. Here’s where Everett Ruess fits in, along with Joseph Halpern and Glen and Bessie Hyde. Readers are encouraged to draw their own conclusions, consider how detectives would handle these and other cases today, and learn how genetic genealogy brings new hope for the future.

Since my book’s publisher only permits a limited excerpt of Cold Case Chronicles, the following pages will paraphrase some of the portions of Everett’s story before concluding with several more excerpted paragraphs.

Missing in the Desert

On February 20, 1935, after three months had passed without a letter from Everett, his mother Stella asked the Salt Lake City Police Department to help find him. The Salt Lake Tribune printed Stella’s brief request, including her comments that Everett was “five-feet-ten inches tall, was well-acquainted with Indians, and knew a considerable amount about outdoor life.” (At the time, the city police had more resources than rural law-enforcement agencies to search for missing persons.)

Reporters for competing Salt Lake City newspapers picked up on Everett’s story, as well. He was last seen in Escalante, Utah and had headed southeast to the harsh and uninhabited area now known as the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. As was his mission on previous treks, he planned to capture the beauty of the landscape with his watercolors. Just a few years out of high school, he already had painted and eloquently written about other parts of the West and Southwest, recording the changing scenes in diaries and letters.

Also missing in southern Utah at the time was twenty-one-year-old New York City resident Daniel Thrapp, called the “boy explorer” by the press. Daniel, on leave from the American Museum of Natural History, in Manhattan, was a paleontologist studying prehistoric cliff dwellings. His parents had last heard from him in January 1935. With two young men missing at the same time in the same part of the state, the police took the missing person reports seriously and called upon the “tracking skill of Navajos.”

Meanwhile, news that Everett was missing was picked up by newspapers all over the country. Neal Johnson, a California resident and gold prospector, contacted Everett’s parents to offer his support after a Utah sheepherder said he had spotted Everett near Fiftymile Mountain, forty-five miles southeast of Escalante. According to the Los Angeles Times, the prospector took off on March 3, 1935 to search the area, asking only that Everett’s parents cover expected expenses for Indian scouts. Before long, reports came in that three Navajos were guiding the prospector and combing the canyon territory where Everett was last seen.

Continued Searches

Not to be outdone, a pilot and a reporter for the Desert News invested in an aerial search –– not for Everett but for Daniel, the missing New York paleontologist. They didn’t spot the young man from the air, but they landed in the town of Bluff, Utah, where, at a trading post, they met a rancher who had camped with Daniel and was buying him provisions. The rancher admitted that he was “highly amused” at press stories fearing that his companion was dead, and instead confirmed that Daniel was “alive and well.” The rancher stated that Daniel was resting his horses on the west bank of the Colorado River, below the mouth of the San Juan River.

The reports of Daniel having been found and Everett sighted (by the sheepherder) boosted the spirits of Everett’s parents and friends. However, their new optimism led to a more-casual approach, at least in the minds of the press, to the search for the missing persons. Articles on Everett and Daniel soon slipped from the news sections onto editorial pages. One Salt Lake Tribune writer, in his article “Searching Utah Mountains” stated, “The rugged mountain ranges of Utah have been crossed and recrossed, over ridges and through passes, along icy streams and down snow-bound trails, from border to border during the past few days, looking for scientists and artists, fugitives from justice and escaped convicts.”

Writing of Daniel, the editor added that “he had settled himself smugly in a remote corner of the commonwealth to enjoy calm meditation and write results.” Of Everett, the editor stated that the young artist “expected to paint landscapes as long as he found the scenery beautiful and interesting.” The editor then added, “That he [Everett] has not returned to civilization seems to indicate that he is still making pictures, while a search is being carried on at the request of perturbed [author’s emphasis] relatives.”

The Tribune writer appeared to have little compassion for missing persons and near-contempt for their families. He concluded his editorial by stating, “On errands of succor and expeditions of justice, men are combing the hills, camping in the wilds, following snow-covered clues, winding through dangerous trails, looking for fellowmen who, for divergent reasons, have hidden themselves from observation and communication. It remains a strange world, inhabited by strange characters whose actions are a constant worry and surprise to their fellowmen.”

Then came a more somber tone in the search for Everett. On March 8, 1934, the Associated Press picked up the story that two burros, thought to be Chocolatero and Cockleburrs, were found starving and floundering in the snow in Davis Gulch, a “slot canyon” along the route where Everett was thought to have headed. The discovery of the burros, however, forced Everett’s searchers to face the very real possibility that the young artist may have become lost, was injured, or was dead. His parents slid onto an emotional roller coaster after receiving the news that no parent wants to hear, “We fear that your son has wandered into the desolate wastes of the desert and is lost.”

Stepped-Up Investigations

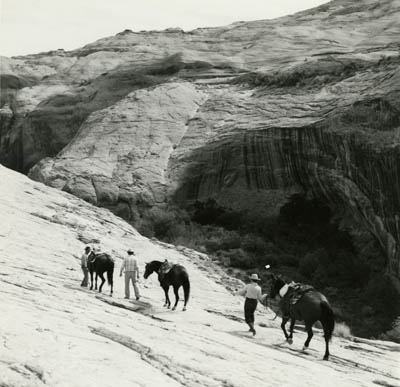

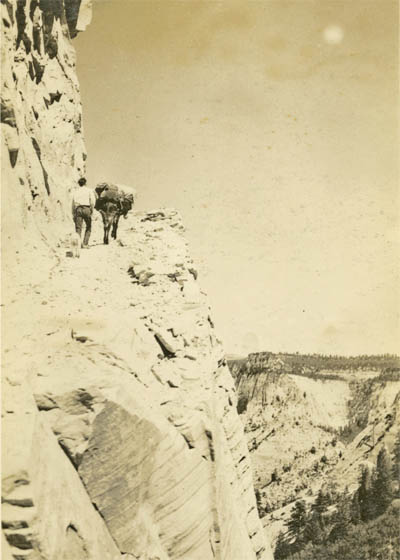

Federal agents, under the direction of the superintendent of Mesa Verde National Park, entered Everett’s search on April 18, 1935. Some still held out hope that Everett simply was holed up in a cave or spending the winter with the Navajos. Subsequent accounts revealed that Everett’s parents held on to that hope, too, especially when trackers found three dead campfires that possibly could have been made by Everett and two companions. A third search team, from Escalante, set out on horseback in May 1935, following the same route of a party of Mormons who, in the fall of 1879, had left Cedar City (in southwest Utah) and descended from the western rim of Glen Canyon through a steep, rocky crevice known as “Hole in the Rock.” A reporter noted that all members of the party “volunteered their services without pay in spite of the dangers of going into a country that is full of abrupt cliffs and ledges, where one false move means a possible fall of hundreds of feet.”

The clue that everyone was looking for was not in “Hole in the Rock,” but, instead, back in Davis Gulch where the burros had been found. There, searchers found the letters “NEMO” and “1934” carved on a rock wall inside of a cave. They also found footprints from a size 9 shoe, believed to be Everett’s. A few days later they found another inscription, this one reading “NEMO 1934.” When Everett’s parents were asked what the inscription meant, they explained that their son knew of the character “Captain Nemo” in Jules Verne’s book Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. They also tossed out a couple of other theories including the fact that Nemo was the Latin name for “no man” (also translated as “no one” or “nobody”), used by Odysseus when his life was threatened by the one-eyed giant Polyphemus in Homer’s classic, The Odyssey. As another possible explanation came from one of Everett’s letters in which he had written that he would be “exploring southward to the Colorado [River] where no one lives.”

By August 1935, Everett still was not found, but the search continued. A prolific reporter for the Salt Lake Tribune named John U. Terrell churned out front-page stories and maps designed to sell newspapers, and he introduced the possibility of murder. “The united belief of the best Indian and white trackers, traders, [and] wilderness residents of southern Utah and northern Arizona,” he wrote, was that Everett “probably met death at the hands of a renegade bad man or Indian in a lonely canyon near the southern end of the untracked Escalante desert.” The reporter’s conclusion was that Everett had been murdered for his pack outfit.

Everett’s brother and parents died without any knowledge of what happened to Everett, but his story wasn’t finished. In the years to come, his legend lived on in the writings of Wallace Stegner, Edward Abbey, and many other authors and journalists. Then, in 2008, a Navajo man (who had never heard of Everett) came forward with an astonishing story.

A New Theory

The Navajo told the account of his grandfather, Aneth Nez, who, in the 1930s, claimed to have seen a young white man with two burros being chased, and then murdered, by Utes. Decades later, in 1961, Aneth had retold the story to his granddaughter. She then waited thirty-seven years to tell her younger brother. The oral history eventually filtered down to a wilderness guide in Utah who called David Roberts, the then-contributing editor for “National Geographic Adventure” magazine. Could the murder victim have been Everett?

As the story was passed down through family legend, Aneth had carried the murdered man’s body to a crevice in a rocky outcrop south of Bluff, Utah. In 2008, the grandson who had heard the story from his sister, went in search of––and found––what, by then, were skeletal remains. Before long, the magazine editor went to look for himself. One major piece of the puzzle that didn’t fit the likelihood of the remains belonging to Everett was the fact that the burial site was sixty miles east and across the Colorado River from where he was last seen and where the burros were found. No one involved in the investigation at the time, however, seemed too concerned.

Modern-Day Forensics

By 2009, speculation and stories had faded into the past, and a rush was on for a DNA comparison to prove that the use of modern forensics could solve a cold case. But, it soon was discovered that DNA analysis is not infallible. In David Roberts’ book Finding Everett Ruess, he stated that the initial DNA comparison to determine if the skeletal remains were Everett’s was made between a molar tooth from the remains and a degraded hair follicle from a hair in a hairbrush that had belonged to Everett’s late brother. The remains were found to have been contaminated in the lab due to incorrect handling, thus the results did not help to resolve the mystery.

David Roberts then brought in Dr. Dennis van Gerven, an anthropologist from the University of Colorado, in Boulder, Colorado. At his lab, Dr. van Gerven reconstructed and photographed the skull, then compared pieces of the jaw with two portraits of Everett taken by Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange. He then superimposed his photographs onto those of Everett’s, and they seemed a perfect match. Dr. van Gerven, as quoted in Finding Everett Ruess, stated, “The odds are astronomically small that this could be a coincidence.” To be certain, however, the process warranted a second DNA comparison that was performed between a femur fragment from the remains and saliva samples from all four of Everett’s nieces and nephews. The results from that comparison were said to have been inconclusive, appearing as a “false reading” due to a “software glitch.”

Now, we return to the conclusion of this chapter:

By this time, numerous people were following Everett’s missing-person case and some, including the Utah state archaeologist, were skeptical. Of particular importance to the archaeologist were the victim’s teeth. Several showed “shovel-like” incisors most commonly found among Native Americans. Although not all of the teeth from the remains had been found, those that were recovered did not match descriptions of the teeth in Everett’s more than seventy-year-old dental records. The dental discrepancies and the burial site’s unexplained location raised big red flags.

Then Everett’s nieces and nephews became concerned and took over making arrangements for a third DNA comparison. This test was performed by the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL) in Maryland. Unlike the previous comparisons, the AFDIL company had the facilities suited to a forensic investigation and compared DNA from both a tooth and a piece of the femur, along with a saliva sample from one of the nephews. These results definitively showed that not only were the remains not those of Everett but they actually belonged to a Native American. But who the man was, no one could tell.

As we have seen, three different DNA laboratories produced three different results. Philip L. Fradkin, the author of the book “Everett Ruess: His Short Life, Mysterious Death, and Astonishing Afterlife” states that the first two labs were not set up, as the AFDIL one was, to accurately analyze older DNA samples. He adds that the experts initially approached by David Roberts and Everett’s family members should have warned them about the facility’s limitations. Emphasizing the fact that they didn’t “indicates a certain arrogance or carelessness within the ranks of this particular branch of science.”

Wilderness Song

Perhaps the best resolution to Everett’s wanderings is that offered in Scott Thybony’s “The Disappearances: A Story of Exploration, Murder, and Mystery in the American West.” The author, a travel and exploration writer as well as river guide and archaeologist, followed up on a story he uncovered about a tourist, in the 1970s, exploring for Native American ruins in Davis Gulch. The tourist found human bones wedged within a crack in a rock, and he left notes as to the location of the remains. This site also happened to be the area where Everett and his burros were last seen, and it also was the area where searchers found the “NEMO 1934” inscriptions carved on the walls of nearby caves. The tourist who had found the bones stated that he left most of them in place, but he gave a few to a National Park Service ranger to give to his supervisor at the Lake Powell marina at Wahweap, near Page, Arizona. Unfortunately, no one today seems to know what happened to the bones.

But the discovery site had been well recorded, and decades later, Scott Thybony returned to find the crack, as described, in the documented rock. By the time of his arrival, however, the area had periodically flooded, and he didn’t find any more human remains. What he did find, though, above the crack where the tourist had found the bones, was a perfect hideaway in the sandstone and a remote campsite wide enough for a single bedroll. In an article in the Durango Herald on May 13, 2017, writer Andrew Gulliford called Thybony’s discovery “perhaps a final conclusion.”

Gulliford quoted the author as stating, “An ancient juniper had been dragged in for firewood, and a small ring of stones had been placed against the far wall.” Thybony added that in his examination of the campsite, there was no evidence of prehistoric use, indicating that it had not been inhabited by Native Americans. Was this campsite the last place Everett was alive before slipping to his death in the rocks below? It seems very likely.

His final artwork and most recent diary may have been blown or washed away, but his letters, his previous years’ diaries and his family photographs are now archived in the Everett Ruess Family collection at the J. Willard Marriott Library at the University of Utah. Everett’s own writings may be, after all, our best source for solving the mystery of his disappearance. The following lines from his poem, “Wilderness Song,” were published during the time of the earliest searches and seem to be prophetic.

Everett wrote,

Say that I starved; that I was lost and weary;

That I was burned and blinded by the desert sun;

Footsore, thirsty, sick with strange diseases;

Lonely and wet and cold . . . but that I kept my dream!

Silvia Pettem is a Colorado-based historical researcher, newspaper columnist, writer and author. After local history research led her to the identification of a decades-old murder victim, Pettem switched from writing about history to the genre of true crime. In “Cold Case Chronicles: Mysteries, Murders & the Missing,” she combines her interest in history with a passion for solving cases involving missing persons and unidentified remains.

In 2010, Silvia became a Medal of Honor recipient of the Vidocq Society and is honored to be among its members. She’s also an instructor in law enforcement training sessions sponsored by the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, and she works (as a volunteer) on missing person cases in the Detectives Section of the Boulder Police Department.

She can be reached via her website, silviapettem.com.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Very interesting article of great interest to all ER followers. Having read all the ER mentioned books and many others, it remains a mystery to me.

Thanks

Yes, a mystery for sure, especially after Scott Thybony’s comments, below. Thanks for your kind words.

ER update:

Last year a curator at the Museum of Northern Arizona contacted me about human remains from Davis Gulch she located in their collections. They were turned over by a man from California in 1975. His description of where he found them leads us to believe they are the bones handed to NPS worker Roe Barney at Glen Canyon. Archeologists have identified them as being from a female, 18 — 22 years old. The mystery continues.

Scott, Thanks so much for your comment. Your work on Everett is much appreciated, even with this new twist. Yes, the mystery continues….

Fascinating. Simplest thing to do resolve whether or not the bones from the Museum of Northern Arizona are ER’s or not might be genetic comparison with living relatives. An accidental fall seems the simplest and therefore most likely explanation for what happened to him. Hope you’ll keep us updated.

Thanks for the great article..this is what makes the Zephyr great

Comments much appreciated…. thanks!

I wonder if the bones from the museum of Northern Arizona could be from ER. Perhaps the analysis was incorrect about the bones being from a female or perhaps ER had female genetic traits.

I wonder if the bones from the museum of Northern Arizona could be from ER. Perhaps the analysis was incorrect about the bones being from a female or perhaps ER had female genetic traits.

I wonder if the bones from the museum of Northern Arizona could be from ER. Perhaps the analysis was incorrect about the bones being from a female, or perhaps ER had female genetic traits.

Good point. I wonder, as well.

fascinating intriguing material for the continued muse(ing). i’ll be on “the watch” for more S.P. articles ~