In the mid-70s, Cisco, Utah was already being called a ghost town. It had boomed briefly during the Uranium Craze, but two decades later, it already had a deserted look and feel to it. One marginal exception was Ethel’s Cafe. Its owner, Ethel Hall, was known for her cranky disposition; I was once advised that if I ever felt I needed more abuse than what was already being served to me, I should pay Ethel a visit.

Being the masochist that I am, I immediately headed north, up the river road to see Ethel. It was in the early spring of 1976, and the weather was still blustery and cold. There was one battered pickup out front and I pulled in next to it, in my foreign-made, VW Rabbit and walked in. I felt sort of conspicuous from the moment I pushed through the door. Ethel was leaning against the counter, a cigarette dangling from the edge of her mouth. She had one customer, who seemed to have permission to be there. He may have been her husband, Shorty Hall, whose disposition could allegedly match Ethel’s, blow for blow. In fact, I got the feeling from the moment of my arrival that drawing more customers was not a priority for Ethel.

Had I been able to gaze a year into the future, I might not have bothered to make this journey. But on this particular morning, in March 1976, I was oblivious to the fact that being a scraggly looking, long-haired seasonal ranger on his days off, and looking very much like “a damn hippie,” might create a certain level of angst for Ethel. And so, innocently enough, I smiled and said hello. No reply. Blank stares all around.

I said, “Could I have a Coca-Cola?”

Ethel glared at me for a moment. Then she nodded to the other side of the room. “They’re in the freezer case. Are you blind?” she snarled. “Get it yourself.”

I pulled a bottle from the fridge but it didn’t feel very cold. Because I have had a death wish for decades, I asked, “Do you think I could have a glass with some ice?”

SNAP!

“What the hell for? You just took it out of the FREEZER!”

Even though it was almost as cold inside the cafe as out, I could feel sweat starting to form around my neck and my ears felt hot. A sure sign that I was terrified. I started to hand her a five dollar bill for a fifty cent pop. Her eyes narrowed even more. The brow furrowed. I said, “Maybe I have the right change.” I dug into my pocket, praised the Lord when I fished out two quarters, paid for my Coke and left. Feeling supremely abused, I savored my lukewarm soft drink, all the way back to Moab. But I never found the courage to return.

*** *** ***

By 1976 and my one and only visit, the fortunes of Ethel’s Cafe’ and Cisco were on the wane. Along with her husband, Shorty Hall, Ethel had seen the little community shrivel in the last decade like a spider on a hot stove. It wasn’t always like that. Cisco was founded as a water stop for steam locomotives along the Denver and Rio Grande Western railroad (D&RGW) in the late 19th Century. And for decades it had become ‘shearing central’ for as many as 100,000 sheep each year. During the late 50s, after Charlie Steen found uranium and the Boom was roaring full throttle, Ethel’s was a popular gathering place and watering hole for hungry, thirsty prospectors. Prices were high and the availability of goods and services there was limited, but her customers were full of optimism. Every wide-eyed, full-of-hope amateur prospector who passed through Ethel’s door was certain he’d be the next Uranium King. There was the glow of optimism in the air, fueled by copious quantities of whisky and beer. The place could get a bit wild at times. It was rumored that Ethel even offered her own personal services, with Shorty’s blessings, to lonely miners willing to meet her asking price.

But the Boom ended in the early 60s, and hard times fell on Cisco. To add insult to injury, the newest section of Interstate 70, from the Colorado State line to Crescent Junction, was under construction, with a 1971 completion date. Almost all the cross-state traffic that had passed directly past Cisco’s front door would soon divert to I-70. Cisco and Ethel’s would be left high and dry. And yet, its greatest glory, its shining moment in the sun would come in the summer of 1970 when key scenes from the independent and soon-to-be cult film “Vanishing Point” were shot in Cisco. In fact, the film’s fiery ending occurs just yards from Ethel’s front door.

But even as the cameras rolled, construction on the Interstate, just two miles north, cranked on. Ghost town status was just months away. By the mid-70s, Cisco was a shadow of its former shadow. The Shell station that Ethel had maintained for years soon folded, but the cafe hung on. Ethel kept the door open, for reasons only she could explain. Customers were few and far between.

In addition to the scarcity of business to begin with, Ethel and Shorty were pretty picky about who they let in the door. One thing for sure, if somebody wanted a meal, they’d better be prepared to pay for it. On the afternoon of June 4, 1977, things got ugly. Shorty and Ethel were sitting at a table with one other customer when a young man walked in, looking for a meal. In those days, anyone whose hair overlapped his ears was a hippie and this kid fit the bill. But he was hot and thirsty and hungry and he ordered up a burger basket and a beer. His name was Tom Asp and he was working out of Grand Junction on a drill rig, somewhere in that area known as ‘the Stinkin’ Desert,’ south of the Book Cliffs. Ethel and Shorty, and their only other customer for that matter, eyed Asp with unbridled scorn. But the boy lingered over his food and finally Shorty got tired of waiting for the ‘hippie’ to leave and walked out the door to do some chores.

Finally, with Shorty gone, Ethel brought the young man his bill and insisted he pay and depart the premises, ASAP. And now for the first time, at least as it was reported in the papers, young Asp acknowledged that he didn’t have a penny to his name. He’d pay if he could, he explained, but he was broke and he was hungry and needed a beer. Ethel lit up like a Roman Candle and screamed him out the door. But Asp wouldn’t leave the area. It’s most likely that he didn’t have transportation of his own and thought the best chance he had at hitching a ride back to Junction was to stay close to town (if Cisco could still be called that). But the truth is, for his own safety, he should have left.

When Shorty came back and discovered the kid had left without paying, he stormed out the door, only to see the alleged miscreant loitering by the old motel, just a couple hundred yards away. Shorty confronted him, the two men scuffled, Shorty pulled out a .22 pistol, and shot him in the abdomen.

What happened next is unclear. Apparently Shorty left the gunshot victim on the ground and ran back to the cafe. Ethel called the sheriff to report the incident, but when they both stepped outside, Asp was inexplicably gone. An hour later Sheriff Heck Bowman arrived on the scene and heard Shorty tell his version of events. Bowman said, “The only thing I know is, it led to words, and it’s my understanding that (Asp) jumped him. Shorty jerked out a little gun and shot him.”

Sheriff Bowman, satisfied that it was self-defense, and apparently not too fond of “damn hippies” either, went back to Moab. He told a reporter that probably, no charges would be filed in the incident.

But the next day, the sheriff’s office got a call from the Grand Junction police. Two men who were traveling eastbound on US 6/50, heading home to Grand Jct, saw Asp staggering along the roadside. He was clearly in distress from a gunshot wound. They raced him to St. Marys Hospital in Junction, an hour away.The Colorado authorities were notified, took Asp’s testimony, and called Grand County. They spoke to Bowman and to the recently elected young county attorney, Bill Benge. Asp was listed in satisfactory condition and within a few days was released from the hospital.

Benge asked Bowman when he planned to pick up Shorty. Heck said he couldn’t see any reason to. Benge was a bit taken aback and argued that since Shorty had indeed shot the man, without witnesses, that maybe the sheriff should at least bring Shorty in for questioning. Bill Benge had come to Moab from the Bay Area in California, and when elected Grand County Attorney, he had become the youngest person to ever hold that office in the State of Utah. A graduate of the law school at Berkeley, consequently, Benge’s views were slightly different from Heck. Heck wavered.

Finally, after hearing from the Colorado police as well, the sheriff decided that maybe he’d jumped the gun. He told the Grand Junction Sentinel, “It appears now there was more to it—there are two sides to look at. What we’ve turned up so far indicated some charges were in order.” Shorty was arrested.

Eventually, Shorty Hall was charged with aggravated assault and released on a $3000 property bond. How the case was resolved, or whatever happened to Tom Asp, is unknown. There is no record of its disposition in the local paper.

*** *** ***

In 1978, someone put a match to part of Cisco and burned to the ground many of the abandoned buildings that had survived for decades. Ethel hung on by a hangnail. Finally, she gave up. I never saw an announcement of the closure. But on a drive to Grand Junction via Route 128, I finally realized that the cafe’s long worn abandoned look was now more pronounced. Ethel had left, to where I have no idea. Years passed and the old building continued to deteriorate.

In 2012 we stopped to take these pictures as a once iconic landmark slowly returned to Nature. I haven’t been by in years now.

*** *** ***

Postscript: If any of our readers have old stories or photographs to share about Ethel or Cisco, please write to us: cczephyr@gmail.com.

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

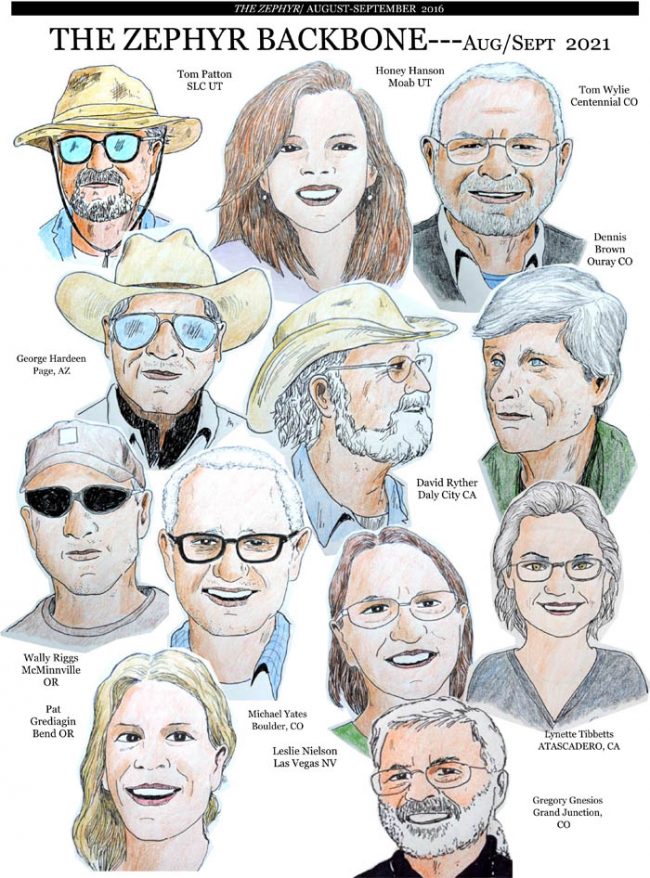

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Hey Jim,

Just read you story about Ethel’s Cafe.

In 1977 I was a rookie boatman for Worldwide Exped in Moab. I probably worked 8-10 overnight trips in Westwater Canyon that season and was intrigued by Ethel’s much like yourself. Sometime in June I decided to stop in and see what she had to offer. I asked for a menu and she said she didn’t feel like cooking thus like yourself, I bought a soda and left. But I was still enamored with the place and stopped in again after my next trip and took all my guests in to buy sodas. Ethel even cracked a smile. All together we stopped in 4-5 times with guests & crew – bought her out of soda one time which I think amounted to 4 Orange Crush. We started talking up the coming visit to Ethel’s during our Westwater trips and had the clients so scared some wouldn’t even get out of the bus when we stopped in. Ethel was always gruff but generally congenial.

That fall I saw news of the shooting in the Times Independent and the cafe was closed by the summer of

1978 when I returned to the river.

One interesting detail I noticed in your pictures is the shape of the cafe changed between 1970 and 2012. What would be the northeast corner of the building was filled in to make the front even all the way across. I can’t recall if it was like that in 1977-1978, or not.

Cheers,

–Robert “Tubby” Tubbs

must be the same place i and crew and associated oil-field riff-raff would occasionally have breakfast at. Might the cafė have been simply named the Cisco cafe? I visited a few drilling sites in the vicinity from 1978 into 1979 — but at least during the earlier part of that stretch, we would eat breakfast (usually, rarely lunch) after a long night at whatever drill-rig we were assigned to. I guess that being oilfield trash, we didn’t notice anybody else (including the staff) being rude and obnoxious ~

I loved your description of Ethel and the story was quite interesting. Sad to see so many landmarks go away.

Hello Amigo,

Great essay describing Ethel’s Cafe in Cisco. I remember it well when i first arrived in Moab on a Trailways bus in the spring of 1972…..a young buck ranger fresh from the hills of Kentucky. Fond memories of a by-gone era.

Best wishes,

Doug Treadway