One of the truisms of life as a reporter, especially in a small town, is one always had to have access to motorized transportation. There was no predicting when or where a news event would take place, and, especially if one was also the paper’s lone photographer, you had to get to the scene quickly.

This was accepted by most of the people who knew me. They also learned to put up with the always-present pocket scanner, and my habit of raising a hand to halt conversation when a call came in, while I listened whether the item was newsworthy (The vast majority, of course, were not). Kris thought it funny that everyone I knew was trained to fall silent at a hand signal.

Also, because I lived with the scanner, I could generally tell when something was interesting, even when the volume was so low others couldn’t hear it, frequently even making judgments by the dispatcher’s tone of voice. Their reward for the imposed silence was finding out what was happening in the community in real time.

My friends also put up with the fact that whenever I went anywhere with a group, I insisted on taking my own car—alone—“in case something happens.” This habit became an issue on Friday, Feb. 29, 1980.

A group of employees from Four Corners Mental Health (speculate if you will why so many of my friends worked at Four Corners) insisted it was high time we went out for a truly civilized lunch. “Truly civilized,” in this case, meant Mi Vida (location of the current Sunset Grill), which was then a kind-of high-end restaurant with a great view of Moab Valley and the Colorado River Portal. The restaurant was located high above the valley in Uranium King Charlie Steen’s former home.

They also pressured me to “for once” provide transportation for at least part of the group in my battered VW Thing—a challenge, since I had replaced the back seat with a platform covering the auxiliary battery; anyone seated back there was perched above windshield level with the top down. In many places during February this would be a bad idea—not so much in Southeastern Utah, if the trip was short and the sun was out on a 69-degree day.

“Okay, I’ll drive, but if anything happens, you guys will be stranded and have to find your own way back.”

“Nothing’s going to happen.”

While finally agreeing to drive, I still dragged along the pocket scanner and camera bag—my security blankets. My friends didn’t object, but then again probably didn’t notice. I was never without them, so they were as much a part of the package as the silencing hand signal.

After the short drive from downtown, we settled in and ordered our meals–for me, my usual French dip sandwich. Of course, in the genteel confines of a fine restaurant, I turned down the scanner’s volume to where even I could barely hear it.

About midway through the meal, the pace of the radio traffic picked up dramatically, although I couldn’t discern the cause over the noise of surrounding conversations.

Far below, a Utah Highway Patrol unit sped north on the highway with lights and siren.

“Probably just a traffic accident,” I thought, “no big deal.” After all, one can’t cover everything, and this civilized lunch stuff is all right. Relax; take a break, Johnny Deadline.

A second UHP unit went by, followed minutes later by a couple of sheriff’s cars and an ambulance. It seemed everything in town with a siren was driving at speed past the restaurant on the hill.

To hell with gentility; I turned up the scanner and tried to make sense of what was going on. It still sounded like a traffic accident, with minor injuries at the worst—probably not worth bothering with. Officers kept talking about the airport, indicating the accident was probably on the highway near the turnoff to the field.

Loath to give up the civilized lunch and unwilling to abandon my passengers, I decided to call Barbara Hunerjager, a friend who was office manager for Mustang Aviation, fixed-base operator of the airport, to ask if she could see whatever activity was taking place on the highway.

“Hi Barb, this is Bill, can you see what’s going on out on the highway? It sounds like an accident or something.”

Her words poured out in a rush, as if we already shared common knowledge of something important:

“They went down just off the end of the runway!”

Went down? Runway? Holy crap, it’s a plane crash!

Nothing and no one on God’s green Earth was going to keep me from covering an airplane crash. Is someone scripting this stuff?

I slammed down the phone, ran back to my companions, grabbed the camera bag and tossed down a twenty, serious money in an era and place where $15,000 a year was a good income, for me, at any rate, and a sandwich at a fancy restaurant cost less than $5.

“Plane crashed at the airport!” I announced. “You guys are on your own. You’ll have to catch a ride with somebody. I’ll get the change later.”

And I was out the door.

My friends were not happy, but there was no way I was going to sit through lunch, ferry everyone back to work, then teleport myself 20 miles north to catch a major story breaking at the airport. I joined the parade out of town, minus red lights and siren, but with foot to the floor. I made it in 20 minutes, which wasn’t bad for an underpowered VW.

About 700 feet north of the end of the runway, I spotted what proved to be a twin-engine Trans Western Airline Piper Chieftain down in the dirt. From a distance, it looked to be in pretty good shape for a crashed plane. I drove as close as I could, then trotted the rest of the way on foot.

The front end of the plane sloped down into a shallow ditch, with a crumpled nosecone and collapsed nose gear. Both props were bent and a wing dinged, but other than that, the craft appeared whole. So did the four passengers who were milling around, two of them dabbing at bloody noses.

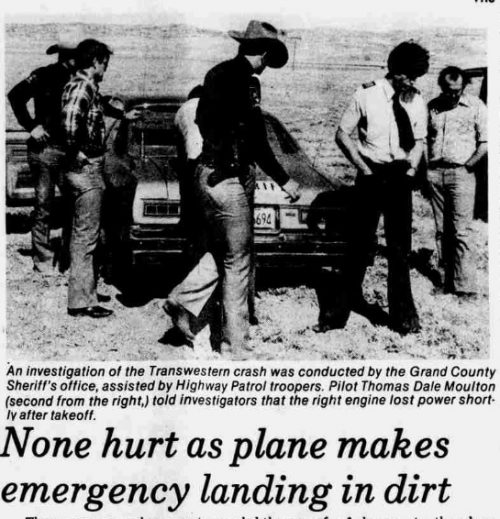

Grand County Sheriff Jim Nyland and Chief Deputy Lynn Izatt were investigating the crash, assisted by a couple of UHP troopers. The troopers were happily diagramming the landing, regarding it as a challenge unique from the typical highway accident.

I interviewed the 29-year-old pilot, who said the plane, the airline’s newest, had lost power in the right engine on takeoff. According to a recent safety directive from the manufacturer, he said, if power on one engine was lost on takeoff in that particular model, the pilot was not to attempt to return to the runway, as might be a natural reaction, but should continue to fly straight ahead until a suitable emergency landing site could be selected. As the aircraft had only reached an estimated altitude of 200 feet, time for making that decision was extremely limited.

Apparently, banking sharply with only one engine operating would cause the plane to stall (Stall speed for the model was listed at 81 mph), likely resulting in a deep and deadly hole. He had done exactly what he should have, and had a mostly whole plane and living passengers to show for it. I spoke to two of the passengers, who praised his actions in getting them safely back on the ground.

The pilot, however, was inconsolable.

“It’s a brand-new plane,” he groaned. “They’ll kill me when they find out. I’ll never fly again.”

I tried to mollify him.

“I’ll fly with you anytime,” I said. “How many pilots know how to crash land a plane? You’ve got experience.”

He shook his head and turned away; that wasn’t what he wanted to hear. I took a photo then that might not have been great art, but sure told the story: Nyland and Izatt can be seen conducting their investigation, while, to the right, the pilot, hands in his pockets, head down and disconsolate, kicks at the dirt, sure his professional life is over. Here’s a link, provided by the University of Utah’s Marriott Library

He had, however, done a good job. He didn’t know it at the time, but had been about to lose the second engine. An investigation by the FAA revealed the plane had been fueled with contaminated gas in Grand Junction. The Piper PA-31 Chieftain had been refueled with a mix of 100 gallons of aviation gas and either Jet-A or Jet-B turbine fuel, a mixture not calculated to react well in turbocharged engines used to 100 octane aviation gas. The airline’s policy, for whatever reason, called for the pilot to check for contamination every other refueling. The contamination check wasn’t due until after the Grand Junction stop. The pilot had been seconds away from total loss of power.

Barb told me later that, as the plane was taking off, Mustang Aviation mechanic Lynn Holyoak, recognizing the sound of a failing engine, jumped up on a chair to look out the high windows of the terminal, shouted “He’s lost an engine. They’re going down,” then ran out the door and drove north along the runway toward a cloud of dust enveloping the downed plane.

I heard later the pilot, far from being cashiered, was eventually named Trans Western’s chief pilot, which I thought was an excellent idea. Who better to supervise pilots than someone who has stuck his bosses’ new plane and four frightened passengers (safely) into a ditch? I had no further contact with him, but I would hazard a guess he never again climbed into an aircraft without checking the fuel for contamination. Heck, had I been him, I would have forever more checked the gas in anything with an internal combustion engine, including my lawnmower.

All four of the passengers, none of whom was a Moab resident, were transported by Grand County ambulance to Allen Memorial Hospital, where they were checked and released.

When I got back to town, I discovered the penalty for abandoning my passengers: change from the twenty. That hurt a bit, as $20 was big bucks in those days—a fair part of a week’s groceries. On the other hand, my friends never asked me to provide lunchtime transportation again.

Tom’s Adventure

Though occurring a short time after I left Moab, I thought I’d include a story told me by Tom Arnold, of Tom-Tom’s Volkswagen fame, describing another case demonstrating how an experienced pilot can get a plane more-or-less safely on the ground after an engine failure, even in Utah’s rugged canyon country.

Tom was kind enough to provide a copy of the FAA accident report and an accompanying photograph when Kris and I visited town in 1985, while attending Utah State University.

Readers may remember from the pot plane crash article that Tom was an extremely experienced pilot, having flown in World War II, and for many years thereafter, including flying shuttles for river trips in Southeastern Utah. He had all major pilot’s license ratings: single-engine, land; multiple-engine, land; commercial, and instrument, with 4,495 hours logged.

On Sept. 4, 1985, Tom was flying a 1970 Cessna 182 Skyline for Redtail Aviation of Green River. His plan was to pick up Colorado River trip passengers finishing their voyage at Hite and return to Canyonlands Field, where the Trans Western emergency landing had occurred five years before.

He had taken off alone from Canyonlands at about 2:30 p.m., climbed to about 8,500 feet and leveled off. Approximately 10 minutes later, over the Green River Canyon “the engine made one Hell of a racket and started vibrating,” Tom said in his insurance report.

“I pulled throttle off, headed for a plateau and started yelling on the radio,” he wrote.

Tom, who knew the area well having flown over it for years, aimed for a landing on a jeep road four miles northeast of the National Park Service Maze Ranger Station.

“The jeep road had two straight sections with a curve in the middle,” Tom reported. “I was too high for the first section and intended to land just past the curve. [The] aircraft hit the ground in a landing position just short of the road (probably luckily) and nosed over slowly after the nose wheel collapsed.”

Tom explained to me that the ground adjacent to the trail was softer and smoother than the road surface, likely causing less damage to the plane’s landing gear. As the plane approached a halt, however, the nose gear sunk into the dirt, snapping off the wheel and causing the plane to slowly flip onto its top.

Tom ended up hanging from his seatbelt, the only injury, he said, a scratch on his face from the pen in his shirt pocket.

A later inspection revealed the cause for the near-total loss of engine power: The number-two piston failed, jamming between the crankshaft and crankcase, breaking a large hole in the engine casing under the right magneto, which snapped off.

Damage to the plane’s nose and cowling, including the snapped-off nose gear, was severe, Tom reported, with lesser damage to the rudder. Fuselage and wing damage appeared minor, although battery electrolyte did spill on the interior.

All in all, it was a good landing, as was the earlier Trans Western incident, proving it is possible to get on the ground safely in a small plane after an engine failure, if the pilot knows what he or she is doing, and is blessed with a bit of luck.

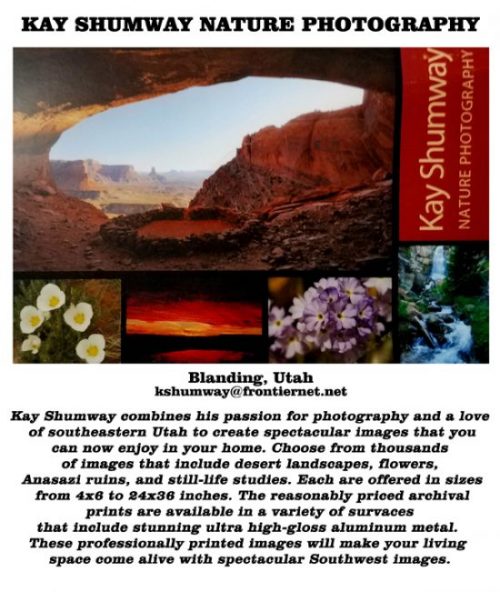

Love of Flying

Given the foregoing (and considering the pot plane crash story), one might assume I’m not particularly enamored of planes and flight in general, but that is far from the truth; I love, and have always loved, flying, especially over Southeastern Utah’s canyon country. You can’t truly appreciate the rugged expanse and intricate drainage system of the slickrock country until you’ve seen it from the air.

One of the perks I seriously enjoyed as a reporter was the opportunity to do numerous flight-related feature stories for The Times-Independent.

The only uncomfortable trip I ever experienced was a Mustang Aviation flight over all three districts of Canyonlands National Park in a Cessna 182 piloted by Moab native Ralph Lemon on March 8, 1979. It was a lovely flight over the main features of the Maze, Island in the Sky and Needles districts. In a change from Mustang’s usual scenic flight routing, Ralph, upon my request, included several spirals over the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers.

Following about six tight 360-degree turns shooting through the downward-pointing side window, I noticed a feeling of slight stomach discomfort. After some fairly rough air over Dead Horse Point, the discomfort became full-blown motion sickness. I was nonplussed, as this was a first-time occurrence after many years of flying in all kinds of aircraft with no problems. Trans Western employee Leni Bryton, who came along on the flight, also turned a distinctive green. Neither of us upchucked, fortunately.

What really surprised me was after the air smoothed out, the nausea didn’t stop until we were back on the ground. This was my one and only experience with airsickness; I don’t recommend it.

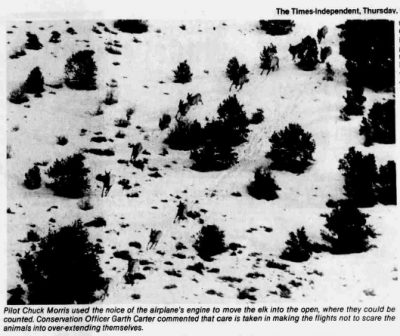

About three years later, I got a call from wildlife officer Garth Carter, who did a regular column for the paper, offering me a seat on an elk-counting flight over the La Sal Mountains on Feb. 28, 1982 (Here’s a link to the story). I jumped at the chance, but, given my unexpected reaction to the Confluence flight, I fortified myself with a hefty dose of Benadryl® before we took off.

The flight was a joy. The mountains were partially obscured by clouds from time to time, requiring pilot Chuck Morris to crank some seriously banked turns when we entered the puffy cotton clinging to the ridgetops.

Every time we stood up on a wing, Garth and Chuck turned around, grinning, and asked, “How are you doing?” apparently expecting I was about to blow breakfast all over the backseat.

“This is great!” I responded each time, not adding that I, for understandable reasons, was half asleep.

Chuck at one point explained that the Division of Wildlife preferred using “tail-dragger” planes with tail wheels rather than nose gear, as they stood up better “in case we have to put her down,” which made sense, considering the nose wheels had snapped off in both of the previously described emergency landings.

Fine by me, I thought. Just wake me before you try that.

The flight reinforced my belief that airsickness and I would once again become strangers, a conviction that has, fortunately, proven true. Chartreuse complexion or no, the Canyon Country, seen from a few thousand feet, rather than the lofty 40,000 feet of a commercial airliner, is absolutely amazing. If you ever have the opportunity to take such a flight, do it. Dramamine® is optional.

However, if you want a truly magic carpet experience, wrangle a seat on a helicopter. I was lucky enough to do so a half-dozen times, in a tale involving a controversial uranium exploration road in the Dirty Devil River country, its reclamation, monkey wrenching, and a flight to Hanksville to eat lunch. That story will have to wait for a future column; stand by.

Afterword: I refer to the 1980 airport emergency landing as “my favorite crash” for the following three reasons:

1. Most importantly, no one was seriously hurt.

2. The crash (or, to keep my pilot friends from yelling: “emergency landing”) actually occurred in an accessible area—a rarity.

3. The incident occurred at some time other than 3:30 in the morning during excessively hot or cold weather, which seemed endemic in most stories involving planes coming out of the sky unexpectedly. It did, however, result in one expensive lunch.

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

One of my most memorable Thanksgivings, rented a plane with a friend and Forey Weldon flew us as low as legal around the park, back in the early ’80s.

Wondering if Bill was on a 2 semi truck crash about 2 miles south of Hole-n-the-Rock, spring of ’79. Another park worker and I were watching the first truck, a tanker, melt into the pavement when we heard a horn blaring and turned around to see a second semi flying down the hill, past a long line of backed up traffic. He managed to weave between the only slot open enough to ditch the truck without hitting anyone. Can’t imagine what went through his mind going 60+ past all those people with the road blocked by a huge ball of fire.

Yes, I covered that, if it’s the one I’m thinking of: It was at Muleshoe Bend; the tanker, which lost its brakes, hit the wall at just over 100 mph, killing a man and woman. UHP Trooper John Mealey handled the investigation. I used some of the shots from that for years in my Photojournalism class as an example of spot news coverage.