There were a number of well-considered reader responses to the essay I wrote a couple of issues ago about the accelerating effect of Covid on growth in southern Utah. Some of the comments extended the conversation in new and interesting directions while others raised questions or pushed back on one part or another of the piece.

In particular, there was some debate in the comments about whether the growth in southern Utah is really novel or noteworthy from a broader historical perspective. Humans have always moved around, after all. Of course, the same question could be asked more broadly about the generic processes of tourism and amenity migration across the New West. Is it even an interesting subject or does writing about it amount to little more than whiny nostalgia?

To explore this question further, let’s start with this point hiding in plain sight: amenity migration is migration. If past mass migratory phenomena like Westward Expansion and the Great Migration are worthy of documentation and study, maybe modern amenity migration is, too. Not because it is entirely without precedent, but because it is worth considering how it may differ in relevant ways from prior migrations. Having emphasized this semantic point, let’s compare a few features of the modern, New West pattern of migration with that of the Mormon pioneers who migrated to Utah about 175 years ago.

Many of the differences in modern versus historic settlement patterns follow from the vastly different economic system of today compared with the mid-1800s. The economy of the Mormon pioneers, like the rest of the country, may have had the emerging features of a specialized, anonymized, market-transactional system, but it was still anchored in highly local agriculture at roughly a subsistence level of production.

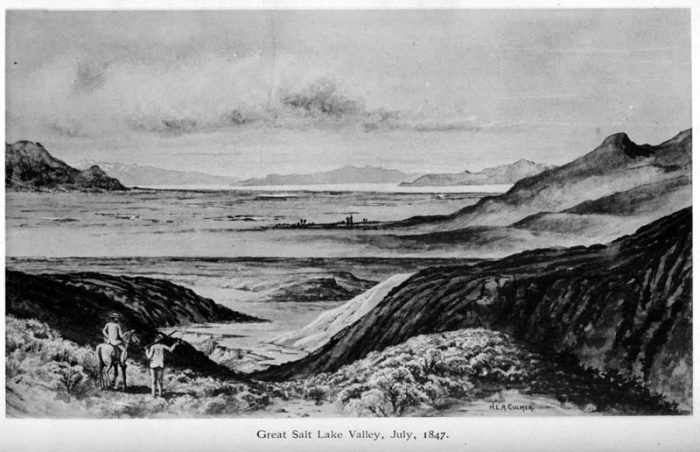

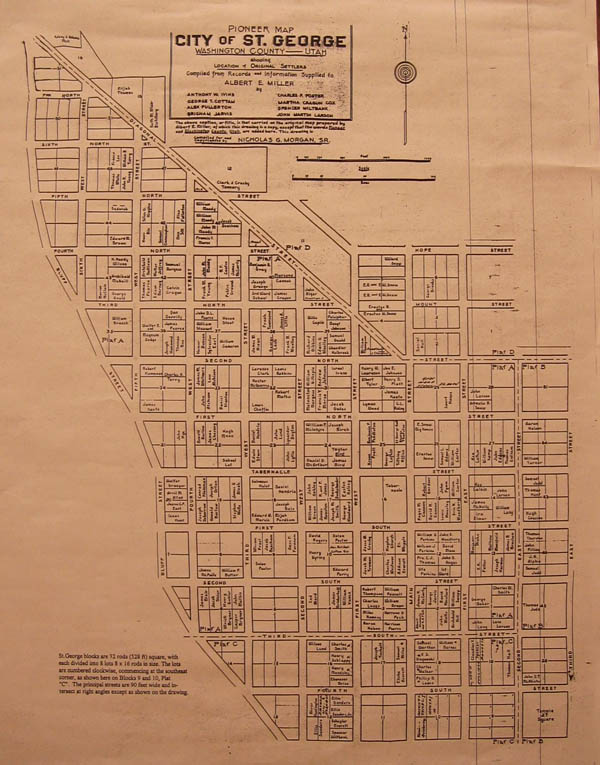

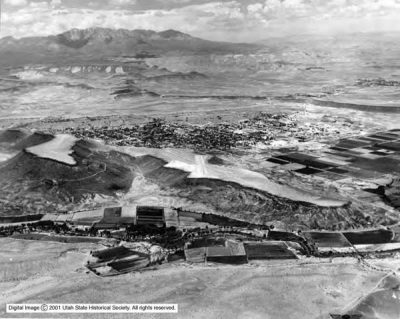

Note that Utah’s Mormon settlement behavior may have been embedded in the prevailing economic conditions of the time, but early Mormon settlements actually were quite different in their particulars from their contemporaries across the rest of the Mountain West. The predominant settlement form in the Interior West during the mid-1800s was the scattered, relatively isolated farmstead or mining camp. By contrast, Mormon settlements took the form of carefully planned and highly prescribed “farm villages,” which is an ancient way of occupying a landscape wherein residential dwellings and social structures are clustered together in a grid pattern and the area surrounding the village is farmed more or less as a commons. This behavior was driven in part by Utah’s rugged landscape and its limited arability, and in part by the fact that Mormon pioneers migrated in relatively large, homogeneous groups compared with the more heterogeneous individuals and small groups that comprised most Westward Expansion. In sum, it is fair to say that early Mormon settlements were defined by unusually close social and environmental ties.

Today, by contrast, the feature that probably most defines the larger social and economic system of wealthy western countries like the United States and underpins New West migratory patterns is alienation. I have written before about the way in which the model two-income professional-managerial class (“PMC”) household sells only their specialized expertise and uses that income to purchase substantially every product or service needed or desired by the household. In the bargain, not only has much of the production of tangible consumer goods been stripped from any local context, but the PMC as a whole has itself become utterly detached from nearly all material production of any kind. Even previously mundane processes like the production of food have become as opaque and mysterious to the typical consumer as airplane flight or heart surgery. This relentless division of labor has produced considerable “economic surplus” in productivist terms, but it has severed most of the ties we used to have with each other and to the land we occupy. What few links might have remained, Euclidean zoning and car culture have further annihilated.

So what’s the point? Am I just complaining about the weather again? I don’t think so. I think a few interesting observations can be asserted from this abbreviated survey.

One is to make explicit a fairly common mental trap: the line between tourism and amenity migration can be a bit blurry, and the pursuit of a lifestyle that approximates a permanent vacation is superficially more benign to our alienated modern mind than the resource-based lifestyles of the migrants of history (or their modern remnants). I think this tendency to find material production inherently repulsive makes it easy to view the ongoing transformation of scenic rural places somewhat less skeptically than deserves to be the case.

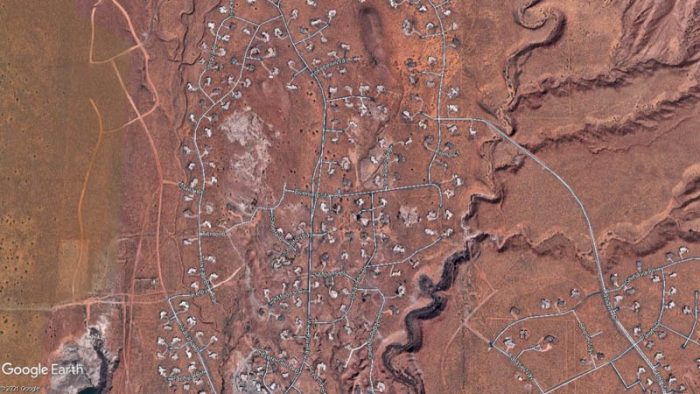

Still, the question remains whether the flow of amenity migration finding its way to previously sleepy corners of the Interior West represents a change of kind or just degree to places like Greater Zion. After all, like their pioneer antecedents, the rural places of modern America are thoroughly embedded in the social and economic structures of the day, for better and worse. Before the first PMC pioneers ever decamped to the New West, more and more stuff was already being shipped into small towns from far away. There have been vanishingly few real local economies for many years now. Since they became common 70 years ago, cars have been pushing the edge of small towns ever farther outwards from the center and puncturing the landscape beyond. On the other hand, it seems to me there is something fundamentally different about a migration pattern that is so explicitly and extremely post-productivist in nature as one defined almost exclusively by the scenic and recreational potential of a place.

In any case, the concession that scenic rural places are cursed with many of the same plagues as suburbia does not absolve any of us of our complicity in these processes nor is it a suggestion that any of this will end well. The forces pushing things in the direction they are going are far more powerful than anything likely to be mounted in opposition. Meaningful change is likely to come only out of necessity. In the meantime, probably about the most any of us can hope for is to dedicate ourselves to something we find personally meaningful.

Stacy Young is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in Southwest Utah.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

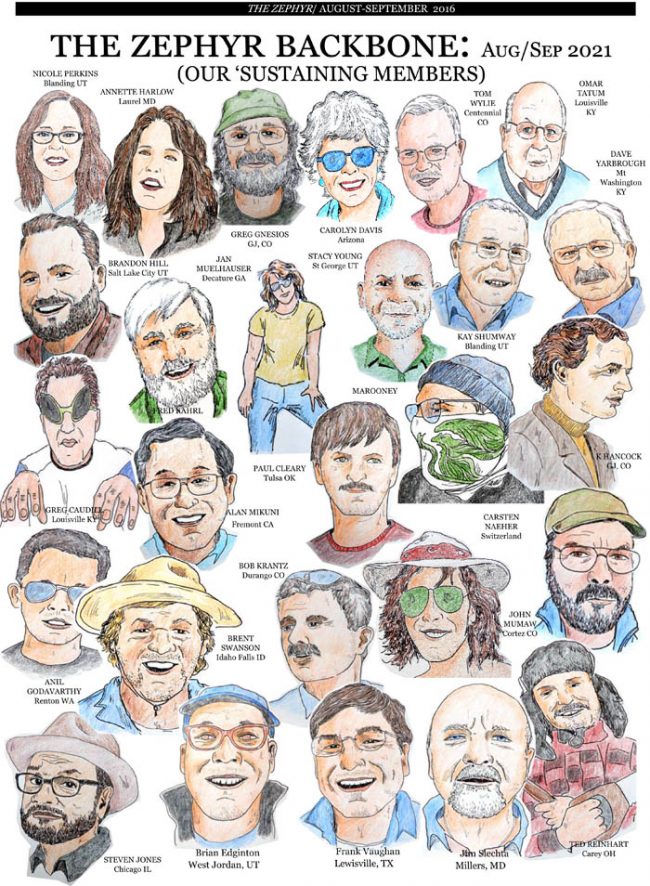

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I can’t remember when I first read about or heard of “aspenification”, but I do remember when the locals got priced out of their town in the 1980s. Just as water flows towards money, money flows towards beauty. The bigger monies flow into gigantic money ziggurats like Aspen and Telluride. Towns like Moab aren’t so much “aspenified” as they are “jacksonified”, as a deluge of smaller monies transform them into national park boomtown carnivals like Jackson, Estes Park, Gatlinburg, etc. This was a great article from Stacy–dense, well reasoned and sufficiently brief as to keep the reader’s engagement while not overwhelming with excessive statistical analysis or academic jargon. Thanks, as always, for good food for thought.

Stacy, it sounds like you are bemoaning comparative advantage, and promoting a Jeffersonian citizen-farmer model. Yes, many people are as ignorant about food production as about flying airplanes or surgery, but if not for specialization, we would not have airplanes or modern medicine to think about. Once we freed 90% of the population from farm work we could begin to develop all the other things that have added significantly to our material lives.

If you really want to see environmental devastation, let’s put 330 million Americans all back on family farms. They would indeed have better ties to the land, and better grasp of mundane (if critical) skills and activities. But would they be better off with the rest of the lifestyle package from, say, 1920? Or 1820?

Another excellent article. It covers a lot of ground and leaves the reader with a lot to think about.

I agree with Stacy that alienation is a problem, though I don’t think it’s due to amenity migration or the Professional Managerial Class. And like he alludes to, alienation—if we define it as being removed from local production, is nothing new.

So, what’s the problem? The New West has a new alienation. Neighbors—old-timers and newcomers—can live in digital economic, social, and entertainment bubbles that reduce the need for people to interact meaningfully with each other and the natural environment. Many booming western towns are comprised of people who share a physical location yet have few shared experiences. I think that this is one thing at the root of complaints about migration, whether propelled by amenity or necessity. Old established towns experiencing rapid growth struggle to hold onto their identity and sense of community. This isn’t good. People need community in order to lead happy, fulfilled lives.

Then there’s alienation from place. Landscapes are filled with stories. Natural and human. Without a basic knowledge of how the local ecosystem works or the stories of people who lived lives closely entwined with it, the land can seem unidimensional to a newcomer—only a place for recreation, an amenity. I heard once that you can get closer to a place if you learn to identify a dozen each of its unique plants, birds, and animals. The list should include a dozen stories each about people, families, and traditions that influence an area’s character. Maybe alienation from place causes some of the New West problems that people attribute to migrants.

Stacy offers a productive path forward when he recommends finding meaningful things to do. One is to support efforts that connect people with their local communities and the unique landscapes in which they live.

Stacy, Thanks for writing such thoughtful articles.

Thanks for this thoughtful and well-wrought piece.

I have a recommendation for perfect viewing accompaniment to this essay: Jon Jost’s great film, Sure Fire, from the early 90s, about a guy from California who returns to Utah to sell plots in a development to Californians. It speaks of the alienation about which Stacy Young speaks here as well. It concludes with a sort of “commitment” to action, but not really of the type that Stacy is talking about!

As for this not ending well, as Young suggests it might: I wonder how the ruins of St. George will look in 800 years? Will what few humans remain–or maybe it’ll be hordes, who knows–look down on the valley and wonder if the faint outline of the Softball Complex was some form of astral worship? Will they look at the remains of the houses–what will be left, oddly rectilinear tangles of copper wire? roof shingles? strange stone patterns around old swimming pools?–with the same romantic glean that current day settlers look at Anasazi ruins? Will they steal the artifacts to sell to tourists and rich people in whatever replaces California?

Amenity Migration, like tourism, is a “wicked problem,” one that will not easily be solved in a world where growth is the First Commandment and profit follows a close second. I would suggest to towns like St. George–or Winthrop WA or Bluff UT or whatever small town is doomed in Arizona or New Mexico or Vermont–that they start zoning and regulating to keep things dense or to keep people away. Of course that will not solve the problem, because those with the means will come anyway, prices will rise, and locals will not be able to live.

Even in the Adirondacks, which has done as well as anywhere, I am guessing, to keep development at bay, the locals are being priced out by the airbnb-ification of the housing supply and by the new remote workers.

I love reading Stacy’s writing, even if it doesn’t paint pretty pictures. Thank you!

Having lived in two such small towns with hordes of migrants (myself included) coming in, I’ve seen that there’s another type of migrant not mentioned. The retiree. Mostly coming from rich urban environments, these elderly folks have cashed out their long-time homes and have retreated from the crowds, traffic, and smog to bucolic aggie communities like Minden, NV or resort amenity communities like Truckee, CA. One difference in the lifestyle is the existence or not of HOAs. Here in Minden, there are what I lovingly refer to as California ghettoes, sequestered by gleaming white plastic rail fencing around cookie cutter “executive” houses. Then there are the older and more “Nevada” neighborhoods with bumpy street grids lined with one acre lots and a variety of housing options and lawn art that would send an HOA committee to the loony bin. A lot of retirees love these places and have moved here because the man can erect an antenna to support his amateur radio hobby, or can plunk a huge metal shop building to accommodate his classic car restoration hobby, or the acre property they’ve purchased is room enough for gardens and animals … the hobby farm. If can park his backhoe in the front yard or plant flowers in an old claw-foot bathtub. Who cares? He had arrived at a more productive activity lifestyle even if it is only a hobby. He is taking that executive level retirement nest egg and finally using it to do what he’s always wanted to do but was afraid of being impoverished and laughed at by his peers.

But then, families, friends, neighbors or other strangers from his former home follow him to this bucolic valley. Soon, the crowds, traffic, and smog also follows. This second generation may be younger and has the attitude that “we’re going to show this backwater burg how it’s done.” sigh! And the first wave of migrants complains about all these new migrants. The farmers and ranchers isolate themselves in their traditional cultures, struggling to keep the migrants from “showing them how it’s done.” And the original residents who have lived in the valley for thousands of years, fume with much-deserved indignation. Yes, as Stacy notes in this essay, humans have been migrating for millennia. And the beat goes on.