He just stepped out for a pack of cigarettes…

It’s been a while since I’ve heard anyone say it, even as a joke. The echo of a father who slipped out the door and never came home. The legacy of a businessman who took a break for lunch and left his old life behind him at the desk. The one who is found, through fate or coincidence, twenty years later serving drinks at the bar in Belize.

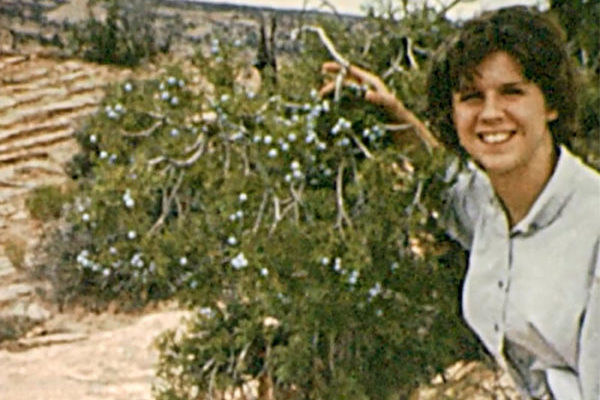

I think of it whenever I hear a case of the missing or the lost. A hiker who doesn’t return from a hike. The traveler who doesn’t call home. I wish for it when I think of Dennise Sullivan, whose fate has been in the wind for sixty years. I wished it again for the missing girl whose body was just found in Wyoming. I like to read the stories of the missing, like last issue’s article on Everett Ruess, and imagine that the least plausible alternatives could be true. No, it’s almost never even remotely likely. You’d have to weave in mysterious head injuries and radical transformations and, in some cases, decades of amnesia; the story becomes too fantastic to believe. But I like to imagine it. Better to think that the missing are simply on a long adventure somewhere.

It came to mind on a recent phone call with my mother. She told me that a man had gone for a run in the Oakland Hills, and he didn’t come home. Search crews were combing the trails. No one had discovered any clues.

What if he wanted to disappear? We both wondered. Wouldn’t that be a better story? Surely that still happens sometimes. Surely some husbands still slip out for cigarettes and escape to another life.

But the doubt follows swiftly behind the hope. In this heavily surveilled world, with cameras and trackers everywhere, could anyone truly disappear?

I did a little research, tracing the loose webs of stories and desires for disappearance that are scattered through the internet. Very little is tangible. The numbers of the missing each year: roughly 600 to 700 thousand. Most of the lost are found again. Over 500,000 are cleared from the system. They, or their bodies, are discovered. The ones who daydream about disappearing are usually only dreaming. The families who are left behind are usually just holding onto fantasies.

It’s impossible to determine how many of the lost were kidnapped, how many lost a gamble against the wilderness, how many were fleeing creditors or bad relationships or the police, and how many just wanted to disappear.

I could only conclude that it’s quite difficult to actually vanish.

A search for manuals on “how to disappear” returns millions of results. But each how-to page gives you the same answers. They all begin:

First, only use CASH.

And then…

Get RID of your CELL PHONE.

In those two sentences, you weed out the dabblers and dreamers. Imagine: to cash out your bank account. To throw away your credit cards. To revoke all social media, delete every file and photo, burn the old letters and take a brick to your smartphone. It sounds a little thrilling, honestly. Then you begin to realize how much more difficult every part of life would become if you couldn’t leave behind any trace of yourself.

These how-to manuals tend to be published on survivalist forums, where you might “also be interested in” a story on locating your nearest fallout shelter… And, now that they’ve mentioned it, I would like to know the location of my nearest fallout shelter… But the tutorials are liberally seasoned with references to “evading your enemies” and “outwitting your pursuers.” So the readers are presumably those with some pretty frightening people in their rear-view mirror, or else those who would like to imagine themselves in that position somewhere down the line.

In these forums, you learn that your enemies will likely hire private investigators. And those investigators, frighteningly, can somehow get access to credit checks being run on your name. This would happen when you tried to rent a new apartment or sign up for utilities. They can follow the trail of your car’s license plate. They can discover employment data, and especially financial information. If your name or social security number is attached to a transaction, they can find it.

After reading for a while, you realize that if someone is looking for you, you can’t be you at all. You can’t keep photos. You can’t get a normal job. You can’t mention your hometown, or go back to anyplace you’ve been, or write to your sister on her birthday. You can’t ever, ever fly on an airplane.

And that’s if you’re being chased by a private investigator. The government is an entirely different thing. They have your facial recognition data, for one thing. Try outrunning your own face…

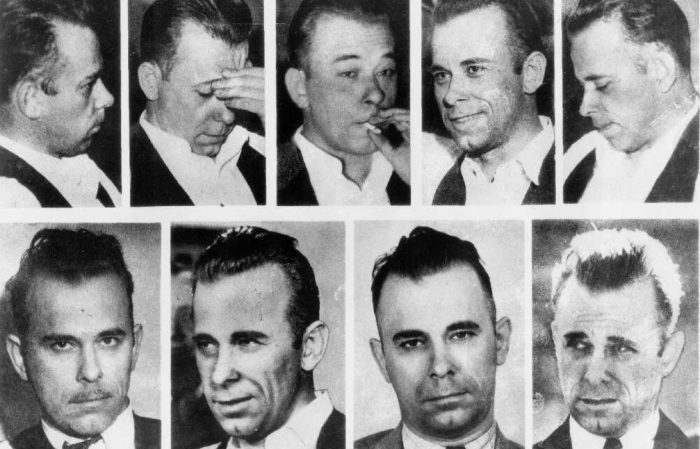

I began to think of the gangsters of the 1930s, who would drive furiously through the night to Reno, Nevada. They could assume new names, and go on the lam with style and money. Not a bad era in which to disappear. Then I thought of the Humphrey Bogart character in Dark Passage; to flee police detection, he had plastic surgery to change his appearance. That story may have been ahead of its time.

After two or three tutorials on how to change your manner of dress, and how to avoid responding to your old name, and how to disassociate yourself psychologically from the person you once were, I was too exhausted to keep reading about disappearing. I had a whole new level of empathy for people who are fleeing from stalkers or criminal gangs. It became clear why most of the deliberately missing are found.

It’s the fatigue that would bring you down, the need to constantly look behind yourself, and question every decision. At any moment, you might inadvertently out yourself . Not to mention the painful loss of all ties to your old friends and family; the inability to form any meaningful relationships in the future. Being found, even if it meant jail, would bring a welcome relief.

This, I decided, would never be worth it. The only reason to choose that kind of disappearing would be if the alternative was death.

The only halfway desirable way to disappear in this era would be to disappear without enemies. With no one chasing behind you. A deliberate stepping away from the world without any dramatics.

In Japan, they’re called “jouhatsu”, which is the word for “evaporation.” The jouhatsu are the ones who evaporate deliberately from the world. An entire industry exists, with companies known as “night movers”, to help the evaporators disappear without notice. One jouhatsu, interviewed for a BBC special on the practice, had felt too overwhelmed by the responsibilities of taking on his family’s business. The man, going by the name Sugimoto, decided to evaporate. “I got fed up with human relationships,” Sugimoto said. “I took a small suitcase and disappeared.”

Simple. Un-dramatic. In time, the evaporated may choose to return. Some remain in the wind.

Some are like Connie Converse, who drove away from her life in Michigan in 1974 and never came home.

I found the story of Connie by chance. But her life story struck me as both beautiful and simple, like the few recordings she left behind. She was a woman who ran away. First, in the early 50s, she dropped out of college and ran to Greenwich Village. By day, she wrote articles for a journal on U.S. Pacific relations. By night, she taught herself guitar and began to compose lovely, intricate folk songs. Born Elizabeth, she was given the nickname “Connie” by people she met in the Village and, at the peak of her creativity, she recorded a series of reel-to-reel tapes of her songs. These would eventually be her legacy; she sent them home to her brother Phil, so that he could listen to her music. She trusted him in a way that she was reluctant to trust the rest of the world.

Otherwise, Connie touched the growing music scene in New York lightly. She was drawn out slowly from her apartment, and she found a small coterie of admirers in the clubs where her friends were just developing into what would be called the Beat generation. But she was too special to survive with them. Otherworldly by nature, she wrote intimate and non-political lyrics for her simple melodies; she couldn’t find her place in the new scene for folk music. She was too strange for that era, and, after a few years, she decided that success would always remain elusive. She was approaching middle age, and she decided that her time had passed. In her frustration, she ran again. She had already learned the habit of disappearing.

Her second run, in 1961, was toward the comfort of her brother Phil. She moved to be near him in Ann Arbor. She found some satisfaction in work for the University of Michigan’s Journal of Conflict Resolution. In the move, she left music and her friends in New York entirely behind her. She made a secret of her past, and kept that secret with herself. She stayed in Ann Arbor and tenuously accepted that life for a decade.

But when the Journal of Conflict Resolution was auctioned off in 1972, and the publication left Michigan for Yale, Connie found herself cut loose again. Having fallen into a profound depression, she began to tell her friends and family that she needed a break. She needed something new. This was the final escape. She drove away in 1974 and no one heard from her again.

However she lived, or died, it wasn’t as Connie Converse. She might have moved to Kansas or Oklahoma. No one was quite sure. No one looked very hard. She had asked to leave them, and they respected her choice. In her own mind, she may have found the freedom she needed. To her family, she had chosen to slip out of the world entirely. She became a mystery.

Only her music remained, preserved with her brother and with the friends she’d known once in Greenwich Village. Decades later, her songs found new audiences. The recordings have been re-released. A 2014 documentary, called We Lived Alone, tried to piece together the details of her life. Other artists have covered her music in tribute. She was likely gone before any of that recognition arrived.

“Human society fascinates me & awes me & fills me with grief & joy,” Connie wrote in one of her last letters. “I just can’t find my place to plug into it.” So she drove away.

It makes sense or it doesn’t make sense. Depends on who you are.

Some of us watched the freight trains pass by as children. They carried the feeling of a dream. Even if your home was a good home and you were safe and loved, there was always a mild claustrophobia. Some questions were never answered: Why is this my life? Why am I this person? Who else could I be?”

I felt a wave of horror at seven years old, the moment I realized that there would be only one trip through my life. I sat on my bed and tried to work out an exception to the rule. But no, there would be only one opportunity to make each choice. Regardless of how many turns I added, there would be one path laid into the earth. And I would only be this person—just this one. No one else. How limiting that thought was. It might be nice to dream, every now and again, that you could trick those limits. Go to the corner for a gallon of milk, and fall somehow into a new life entirely. It’s just a dream. Most people don’t want to cancel their bank accounts or run from the law. They might just imagine a lightening of the burden of self.

I do think the world has weighed heavier on all of us in recent years. There seems to be more appeal in the idea of lightening that load. More people are talking about minimizing their possessions, or owning less in the first place; more think of quitting their careers, or making a life on the road. Whether they succeed or not, whether the dream even makes sense, they are born from the same motive. All these attempts are small acts of disappearance. It’s all tied to that same feeling of wanting to slough off the weight of this world.

The bulk of that weight now lies in this digital “self” and the seemingly inextricable tie between the real and unreal world; the sense that, while the latter grows, the former feels like it is shrinking away.

The online self is an identity costumed as data—and it’s so heavy. It’s far less changeable than your real self. It continually gathers the heft of a lifetime’s context. All the details of your jobs, all of your purchases, every photo posted or chat exchanged, and all the interactions that make up your friendships and family ties. Increasingly it’s where your memories live. The weight of all that data is multiplied in servers across the globe, where it proliferates and indexes itself and is bought and sold to be used against you. And somehow, the weight of that data rests most heavily in your back pocket. It beeps at you regularly from that paradoxically thin shiny prison. Tethered to that phone, it’s no wonder it feels like your responsibilities are holding you with a tightening grip. It’s no wonder that “self” seems to be stealing time and joy from you.

I notice how much better I feel on days when I keep my phone silenced. I know I would be happier if I left it behind entirely. I may talk about the romance in disappearing, but that’s because I’m a romantic. I like my actual life and if I ever vanished from anything, it’s digital self I would prefer to leave behind, in favor of the real one. My real world is a comfortable one. It contains the husband, and cats, and all the things I love. But I do enjoy the idea of that one particularly decadent form of disappearance. Disappearing from the cyberspace—maybe the boldest form of disappearance that remains for us now. Evaporating out of that unreal world.

I could easily see myself deleting all the data of self someday, in order to make my life from only real materials. That would be enough of a disappearance to make the world new again. To feel lighter. One day I would love to call in the Internet’s night movers and slip back into the real material of my life. What a nice way to disappear…

“Now, miss, why did you throw your phone under that Mack truck?” the responding officers will ask me.

“What? My phone? I don’t have a phone, officer. I’ve never had a phone. I was only walking down to the corner for a pack of cigarettes…”

Tonya Audyn Morton is the former publisher & managing editor of The Zephyr. She is now the founding publisher/editor and frequent contributor to “Juke,” an arts and literature journal on Substack. Zephyr readers can access Tonya’s page here. And on Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Interesting article. Several years ago there was one season of a show where several people were on a mission to disappear. They were each given a certain amount of cash and they had to elude police, cameras, etc. It was interesting and your story was enjoyable to read.

Interesting article about disappearing Tonya. Many decades ago,one dark Summer night, I witnessed a giant black triangle UFO pass over where I was living. It was deep in the countryside away from any large towns. I thought I might be abducted, as in aliens wanting to check me out, but it didn`t happen. I was left with the memory of the apparition slowly dissolving into nothing as it drifted away.

Tonya, the title of your article so interested me that I read the entire article. As you get older it is easier to disappear from public notice and thus, in a way, return to a real life without any one bothering you. Mostly, for me, this happens when the demands of a job and the people interactions required there, cease. However, I do enjoy greeting people who remember my name, mostly at church, and care about me as a person. As always your writing is clear and you are able to use the written word to invoke feelings and understanding.

I feel very connected to the sentiments behind this piece. I’ve always romanticized about disappearing in the dark of night, hopping a freight train, and heading North. The connection to the digital world only intensifies this feeling.

Wonderful piece of writing. Thanks for sharing.

How often have I dreamed of disappearing .. or at least running away. It seems like I’ve rebooted my life several times by moving away, finding a new job, or cleansing my social roster of negative friends. Recently, I discovered this poem I wrote in a file of papers I was throwing out … another form of disappearing, right? How cathartic! Anyway, this poem:

Memory of a Distant Past

A window glazed with sunset

Made rust red by refinery smoke

Silhouette of a jet airliner

Rises to the skies

Please take me with you

Help me to forget

All that I despise.

Facebook August 7, 2020

You notice I posted it, and all my other poems, regularly on Facebook. It’s my YAWP in the wilderness. We humans have two strong urges. You’ve skillfully written about one of them in this splendid article, Tonya. The other is to fight against anonymity. We also want to be noticed, center stage, heard singing our songs, finding out audience. Connie Converse’s story seems very close to mine. She sang to anyone who might listen and when she discovered they weren’t listening, she turned her back on them and walked away. How many times have I done that same thing. Turned away in search of a new audience … or to indulge in anonymity. The only thing about disappearing that really doesn’t work, though, is realizing you may run away from people and circumstances, but you’re still stuck with yourself. And the only cure for that isn’t a viable option for most of us. Thank you, Tonya, for a poignant and haunting article.

sue (previous) says “you’re still stuck w/yourself.”

however, as all commenters before: XXX-sell-ent writing, the words wrapping up and around the meaning, what is being conveyed, so well.

I wonder about the people who could disappear, and no one would look for them, or miss them. I suspect there are many.

When I was young, I wondered what it would be like to cut all ties to my past, and write a new story for myself, strike out on a new trail. But thinking of how that would affect family, and to a lesser degree friends, put that notion to rest.

The nearer the end to the trail, the more you think about what trail you’re on. Would the path you chose be worth examining? Would that be important?

Tonya: You did a terrific job with “How to Disappear.” And, thanks for mentioning my article on Everett Ruess. I don’t believe he chose to disappear, but I believe that the thought that he could have is what makes his story so compelling. You wrote of the digital era, but, before then, it really was easy to disappear. I also researched the two “lives” of Twylia May Embrey, a young woman who left her home in Nebraska in 1952 (after her father raped her), then assumed a new name, a new life, and even a new Social Security number. She died under her new name, near Boston, in 2006. Her double lives were not revealed until 3 weeks after she died. Another young woman of the 1950s who created a new life for herself was Katharine Farrand Dyer… have written about her, too. It was hard not to with such an interesting topic. Thanks again.

It’s been so long since I’ve read anything other than items related to our various “have to” documents and Covid recovery. How intriguing and engaging your disappearing article was! It was compelling and informative at the same time. I seldom have time to read anything from start to finish…but your article broke that barrier. Perfect start to a cold wintry feeling day.

Alaska is full of them. They are called “end of the roaders”. The Pan American Highway ends at Homer, Alaska, and the road just goes into the water as a boat ramp. There are a thousand of them living in the woods around Homer because the road stops, and they stop.

Christopher McCandless and Timothy Treadwell were both end of the roaders at different Alaskan places.

‘Trick those limits’….’Thin, shiny prison’……..Gold, Zephyrs…..Pure gold……

I reread this today 2 days after the authorities found the remains of Brian Laundri who was Gabby Petitos boyfriend and person of interest in her murder. I felt such sadness. One because he so maligned throughout the search for Gabby and we may never know if he was her murderer or not. He disappeared but at a terrible cost. In the meantime I wonder about one of my brothers who “disappeared” 38 years ago. He would occasionally call siblings sober then drunk. He would occasionally email me. 7.5 yrs ago he showed up on my FB messages asking about the photo I posted of my new grandchild. I asked where he was and he said Thailand, which is where he was for years, we think. I figure I would not recognize his 71 yr old self if I passed him on the street. But 5 yrs ago there was a photo of him on a blank FB page under his name there was no denying the resemblance to our father. Complete erasure of his surroundings, no info. My 3 other siblings think he is dead…but there is no proof of either his death or his living. Maybe if we paid for a private detective we could find him but honestly why? He obviously wanted nothing to do with all of us. Who knows? He may hit me up on FB again and if I ask him where he is..it will be Thailand and he will disappear again. It was so sad for my Mom to not know where he was or if he was ok. She died and he never responded to emails.

Tonya? Tonya who?

Perhaps you have heard of a fictional character, Jack Reacher, created by the author, Lee Child. He lives in sort of a gray area, between being elusive, off the grid, and being connected, albeit briefly, to the places and people he encounters when traveling, often by bus on his eternal journey through the country. He has few possessions, other than his clothes, some cash and a toothbrush. Child often describes bits and pieces of the efforts Reacher has made to avoid detection. I imagine that one could piece together a set of instructions for disappearing from reading eight or ten of the novels. They aren’t necessarily great literature, but the author tends to go off on fact laden tangents that can be informative.

First, I’m not the Steve Moore who commented earlier. Didn’t know I have a namesake reader of CCZ. I guess if I wanted to disappear I could use the other Steve as cover.

Interesting article and commentary. A side note; regarding the runner in the Oakland hills, I heard that his body was found–death from heat stroke.

We could easily have had a disappearance late this last summer at Natural Bridges; a Park visitor witnessed the man fall from a remote cliff. Had he not been seen actively falling, chances are his fate would still be unknown.

One of the most interesting stories I’ve read was about a seasonal backcountry ranger, who worked in Sequioa-Kings Canyon N.P. The book is titled Last Season. The ranger had cancer and it seemed to be believed that he purposely lost himself so that he didn’t have to deal with cancer treatments.

Well written. Again.

Thanks.