A is for Amy who fell down the stairs

B is for Basil assaulted by bears

–Edward Gorey

When the apple was ready she painted her face and clothed herself like a peasant woman, and went across the seven mountains to where the seven dwarfs lived.

–Brothers Grimm

It’s curious what we get comfortable with as we get older. Take olives. Olives didn’t make sense to me as a child. Why would anyone eat an olive? They are slimy. They smell bad. They taste bitter. When I was a kid the only olives around had this fleshy red filament stuffed inside them called a pimento. I still don’t know what a pimento is. But then life goes on and one day you eat another olive. Who can say why? Maybe you want to find out if they really tasted that bad. Maybe you wonder again why adults enjoy eating them. So you eat one, and you realize it’s not so bad. The next thing you know, you’re in Whole Foods off Cerrillos Road in Santa Fe, trying to catch a meal from all the free samples, which includes a healthy dose of olives. They are displayed in wonderous variety and not a pimento in sight. They come in different shades, textures, vinegars. You soon speak of olives as others speak of wine. You’re an adult. You forage for olives at Whole Foods. They are delicious. And that’s how we go. We get older and get more comfortable with certain things, like olives, like ghosts.

Even now, smack in the center of middle-age, I’m not entirely comfortable with ghosts. I will go looking for olives, but I will not go looking for ghosts. I tend to avoid ghosts wherever they’re present. I am not a man, for instance, who will try to sleep in some dilapidated house in order to tempt the awakening of its spirits. I will sleep outside before I sleep in a place where “something” is present. I will sleep on a roof. I will sleep in bushes. I will sleep on a park bench. I have managed all three in my considerable experience, as more than once the suspicion of a ghostly presence has driven me to the security of the great outdoors or a stiff park bench.

Perhaps most paranoias start early in life. Mine did. I recall being around 5 or 6 when the witch from Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs appeared in my closet. The Evil Queen’s arrival in her haggish form happened on an honest-to-goodness dark and stormy night. I was sleeping in an unfamiliar bed in an unfamiliar room, while outside a storm tossed the world to pieces. Although I had trouble sleeping, I remember a specific instance when a bolt of lightning lit the room. At that precise moment, I fell out of the bed. I recall falling and how the blue refulgence of the room receded as I fell and hit the floor. I came up in an instant. I looked over the top of my bed and there, in an open closet, was the Evil Queen. She was the hag, hunched and horrible. There were no apples, but she extended her hand towards me. Then she was gone.

To this day, I dread speaking about the Evil Queen. She stayed with me for years, though I never saw her again. She nearly showed herself one night while I was home 3 or 4 years later. She appeared at the foot of my bed in a dream. Mercifully it was only a dream, and because of this, I was able to push her back into whatever troubled part of my consciousness she resided.

My father’s grandmother on his mother’s side was terrifying. I have thin but real memories of her. She wore her hair in a tight, snow white bun, fixed exactly on top of her head. Her eyes were the palest of blues and stood fixed with black, candy drop pupils, staring into the vagaries of relative dimensions. Dad told me she had confronted him when he was a boy, telling him that he had the Devil in him. Which could only mean to my Pentecostal great-grandmother that the actual Devil resided in my actual father. This was clearly not the sort of description grandmothers impose on their grandchildren, but then we are talking about families. The weirdness within families has no boundaries. They called her Nana, sometimes Nana B., and when Nana B. died, I felt somewhat relieved, at least until I was asked to sleep in her former bedroom. The Devil was far more likely to live in Nana’s bedroom than in my father. If not the Devil, then one of his close associates, which would certainly be a ghost. I am not sure why, but I didn’t believe it would be Nana’s ghost.

I never learned what ghosts lived in Nana’s room. There were stories though. There were hints of a man in a cloak and a shadow that formed without light. Both remain unsettling.

Yet even with degrees of verification, as with Nana B., the Evil Queen, shadows and cloaks, most of our encounters take the form of a story. Many of them are second-hand, though sometimes, we must admit, they are close. I had a friend once who saw a little man in his grandfather’s photography studio. The studio had belonged to three generations of his family. At the time of the encounter, my friend, who occasionally worked in the studio, was closing down. As he was closing, he said, he caught sight of a little man staring at him. When they met eyes, the little man snickered and ran away.

“How big was he?” I asked

My friend held one hand above the other.

“About a foot and half.”

“What did he look like?”

“Strange.”

“What do you mean strange?”

“He was strange looking. He was bald with pointy features. Pointy eyes, pointy ears, pointy nose. He had very white teeth though.”

“That’s creepy.”

“Yeah that’s creepy. Teeth like that.”

We drove another mile or two.

“Are you serious?” I asked him.

“Yeah I’m serious. My grandfather knew about him. He wasn’t evil looking, you know. He was more menacing. Those white teeth and a pointy bald head.”

I remained silent for another mile or two.

“Are you really serious?”

“Yes I’m serious.”

“You saw this creature?”

“I don’t know if would call him a creature. He was a little man.”

A little man seems more plausible than a ghost, but what the little man is, I have no idea. A gremlin? A demon? A rather exact figment of someone’s imagination? These are all possibilities, including that the little man was…well…the little man. I hope never to see a little man, but I have caught myself looking. I have glanced up from my computer screen or whatever book I happen to be reading, sensing that the little man was staring at me, grinning. No one wants to see a little man staring at them. Aside from whatever the little man is or is not, this is a story and one from my adult life. I was not a kid feeling traumatized by another Disney movie. This was between grown-ups.

The point is our ghosts and ghouls are often more about story than about creatures who exist amongst us. Yet some stories singe us with their reality. They’re a little too strange.

Anyone who has met my father soon understands he is a storyteller. His stories have tremendous range and flavors. There is the one about the young couple who had convinced themselves they needed a fishing license to get married. There is the one about driving with his Uncle Sam to various drinking establishments along the Gulf Coast and how at 5 or 6 years old he was cradled against the formidable breasts of formidable women, as they danced to Lefty Frizzell’s “I Love You Mostly.” There is the one about the military training session in which my father gathered enough wads of C4 to blow-up the training facility. The idea had been for each soldier, my father included, to detonate a small piece of C4. Each soldier was expected to place the C4 inside the training grounds, rig it for detonation, run back to a safe point, and then trip the explosive. Dad did all of this. Except he had secretly rolled those bits of C4 he had collected into a sizeable ball. He followed the same pattern as the other soldiers. But his detonation, much to everyone’s surprise, marked the end of the training facility and also the training session.

Dad is a vessel of stories. Some of Dad’s stories are unsettling. Dad is a man of big medicine, and like all men of big medicine, he has witnessed first-hand the unexplainable. I so much believe in their otherness that I refuse to write about them, not here anyway. Why risk an encounter within my father’s area of specialization? That being said, he did tell me about Mr. Stowebridge. To speak of him—or it—seems safe enough.

Fifteen years ago my mom and dad lived in a lovely old home in a lovely old neighborhood, while the surrounding town existed as a perpetually wounded animal. Nevertheless, mom and dad’s house and the neighborhood to a lesser degree was a generous sanctuary in this leaky scar of a village. Their home had been built in 1928 of brick and stone and kept the façade of a gangster hideaway, think Capone, think Lansky. Inside their home, narrow oak boards formed the floors of the dining and formal room. There was an unnecessarily large fireplace and mantel, three upstairs bedrooms, and a sizeable bathroom fitted with a deep bathtub. The half-acre of property on which their house sat, blossomed with trees and flowers—banana trees, golden rod, azaleas, bougainvillea and a host of other specimens. Life was full there—in yard and neighborhood—with a dead man in the fern patch, thieves evading police in the backyard, a likely prostitute and her pimp in the house next door, and one serial killer who roamed the neighborhood for a month or two before being caught by an old woman who ran a tough man’s bar out near the coast.

I forget how long my parents had lived in this house before my father started talking about Mr. Stowebridge.

“Who’s Mr. Stowebridge,” I asked him one evening.

“He’s the old man who comes to visit me.”

“What do you mean? Like an old man in your church?”

“No, just Mr. Stowebridge.”

I sensed where this was going.

“Who is he then?”

“He’s Mr. Stowebridge.”

“Uh-huh.”

“He comes around late at night, checks to make sure the front door is locked and then wanders away. He’s harmless.”

“So you’re talking about an old man who comes to visit you late at night and checks the locks?”

“That’s right.”

“Alright,” I said.

“He’s a ghost.”

I took the bait and ran with it.

“Can you say anything else?”

“Not really. I think he’s nice though.”

“What does he look like?”

“He’s an old man. Dresses like a normal old man. He checks the front door and then off he goes. I’ve seen him a few times.”

We talked in what my father called his television room. The room stood at the far end of the formal room, away from the fireplace, as though it may have been a cloak room or a separate entryway in another era. Dad pointed at the open doorway between his television room and the formal room.

“I never see him directly, you know. I see him out the corner of my eyes.”

If I had been a kid, Dad’s story would have cost me a minimum of six months of sleep. Yet I had become more comfortable with these stories, just as I have become more comfortable with olives.

Then this happened, and this is true.

The house had only three previous owners. Two of whom were dead and maybe gone. But the owner of the home prior to my parents—a very nice couple, as my parents described them—one day dropped by for a visit. This couple had loved the house and wanted to see it again. They wanted to see what my mom and dad had made of the old place and property. As my mother and the previous lady of the house sat down in the kitchen to glasses of iced tea, my dad and the former gentleman of the house went into the T.V. room. They were visiting, drinking tea. Then the man looked at my father, gave a moment’s hesitation and with something almost like smile, asked my father, “So, have you seen him?”

My Dad asked, “Seen who?”

The man smiled all the way and nodded knowingly at my father. “The old man who comes and checks the locks late at night. Have you seen him?”

***

As a child, my father would not have been so cruel to tell me about Mr. Stowebridge, “nice,” though he might have been. But I still shiver at the story. If Mom and Dad had continued to live in that house, I don’t believe I would have sat up late looking for Mr. Stowebridge. Yet somehow, I would have minded him a little less than when I had a been a child. I’m not sure why. I’m not sure why I appreciate olives now and didn’t as a kid.

I wonder if this tenuous shift in perspective has something to do with proximity. I love stories, and I love hearing stories that older people tell. I want to hear about the hayricks where boys and girls met and came to know each other. I want to know about mothers who pulled their children out of their beds to sleep in another house when they thought some bad spirit had entered their home. I want to know about uncles who hid radios during the war or about forgotten rooms that have been rediscovered and about dolls hidden away in attics in a time of sickness and death. Such stories add a little more life to our passing lives, as if to remind us that it’s okay, they’ve already gone before us.

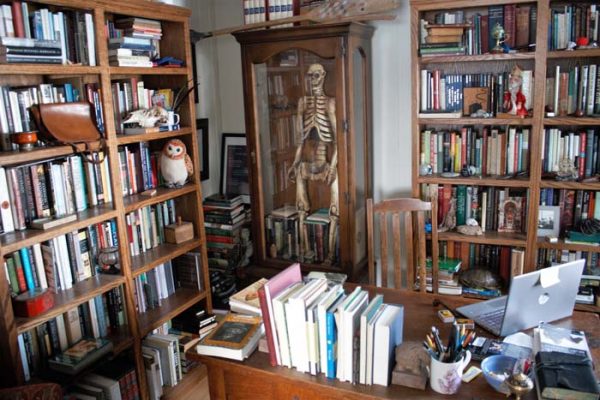

So when a neighbor recently told me that the old woman who had lived in my old house died in the very room where I keep my office and where I spend most of my time, I tried to extract some measure of charm from this fact. What else am I to do? I all but live in my office. I keep my books here. Ed, my human-sized cactus skeleton, lives here too. Ed is incased in a narrow walnut gun safe I inherited. In the case and stacked between Ed’s boney bony feet are books about death, dying, and ordinary weird. A selection of these books includes: The Oxford Book of Death, Grave Matters by Nigel Barley, The Club Dumas by Arturo Perez-Reverte, The Book of Murder by Guillermo Martinez, Ghosts and Ghastlies selected stories by Helen Hoke, Edward Gorey’s The Ghastlycrumb Tinies, and 101 Uses for a Dead Cat, to name a few. This is the room where Anna died. Anna, the lady who saw through the building of this house and then passed her days here.

I was told Anna had a habit of killing animals, pets that is to say, with a hatchet. More than one infirmed dog or kitty had been lured to the woodshed over the years, where Anna, with practiced aim, vanquished the animal into Glory. I found this information more weird than chilling. I asked another neighbor about this practice. He nodded like it was something common to all. He said, “Veterinærer are sort of new here. So, it’s the hatchet….” He lifted his arm and made a putch sound, as he brought his arm and invisible hatchet down.

Rather than her soul adrift in some purgatory, I trust Anna is in some heavenly place among the mercies of her euthanized pets. Or maybe just knitting somewhere. I’ve been told, “She was a very nice lady.” Be that as it may, I don’t want her hanging out with me, least of all when I’m writing late at night. But I’m glad to know she is nice. We share the same space, after all, deep and wide as it is.

Damon Falke is a regular contributor to the Canyon Country Zephyr. He is the author of Now at the Certain Hour, By Way of Passing, and most recently The Scent of a Thousand Rains and the forthcoming film Koppmoll (2020), which explores memories of War World II and home. You can find out more about his work at: damonfalke.com, shechempress.org and on Facebook.And you can click HERE to read more of his work in the Zephyr.