For most of my time at The Times, Thursdays were my “wind-down” days, the one day in the week when I could relax a bit from production pressure, research my much-loved (by me, at any rate) Looking Backward column, and indulge in my substitute for “comp time,” a benefit, which, given the paper’s intense schedule, was officially impossible.

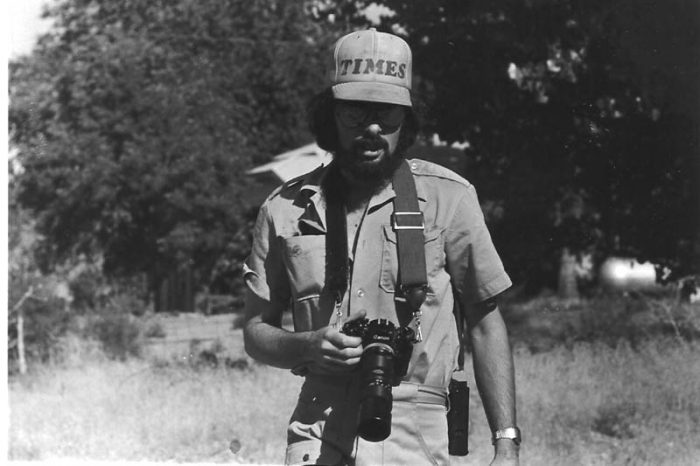

It was known, but only silently acknowledged around the office, on Thursdays when I announced, “I’m going out to get some feature shots,” that I was heading into the canyons and/or mountains to regroup, depressurize, and very specifically not think about the local politics and disasters dominating each week, and weekend, more often than not.

I always came back with an improved attitude, and of course, some publishable photographs—no need to go crazy with relaxation; another issue was always coming up.

Frequently, my destination was Arches; it was close by and relatively unpopulated in that era, especially during the off-season. In peak season, there was the compensatory benefit of visiting with the cute lady ranger at the entrance station, with whom, it turned out, I would live for at least the next 41 years.

The trips were even cheap, after Chief Ranger Charlie Peterson instructed Kris to let the local reporter in for free, thus eliminating the $1 day use fee—a privilege I appreciated and thoroughly abused. Frequently I would take my ancient Jeep into Salt Valley and over the Eye of the Whale Trail, one of the few four-wheel-drive routes in the park. I never, on any of these trips, encountered another vehicle.

Farewell to Thursdays

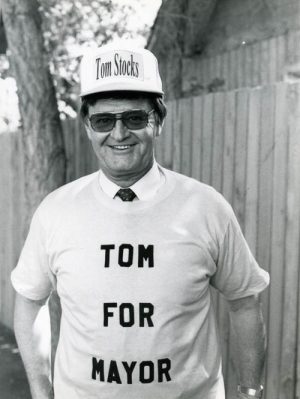

Those idylls came to a temporary but screaming halt during the winter of 1984, which, as it turned out, was my last as a reporter, when Moab City politics hijacked my Thursdays. I soon found myself up to my eyeballs in a controversy over the city’s form of government, involving Mayor Tom Stocks, who was elected in 1981, replacing Harold Jacobs.

Stocks had run for office on a platform of changing the form of city government from “weak mayor, strong council,” to “strong mayor, weak council.” Under the former, the day-to-day running of the city was the responsibility of a hired city administrator, under the direction of the city council. Under that system, the position of mayor was largely ceremonial, other than the occasional responsibility to break ties when the council was deadlocked.

Under the strong mayor system, the person elected became the chief administrator of the city—a full-time, paid position.

Tom didn’t waste any time; after being sworn in on Jan. 4, 1982, in the first council meeting of the new year the following day, he proposed being named administrator, at an annual salary of $24,000 (a lot more money back then that it is now).

The proposal was rejected on a split vote, with continuing council members Marjorie Tomsic, Ken Brewer, and Dave White agreeing to hire a new professional administrator to replace Ralph McClure, who had just quit, and new members Sheldon Hefner and Ed Neal agreeing with Stocks’ proposal.

Personally, I had always been suspicious of elected officials creating taxpayer-funded positions for themselves, especially in the midst of a major recession, such as was under way in Moab at the time.

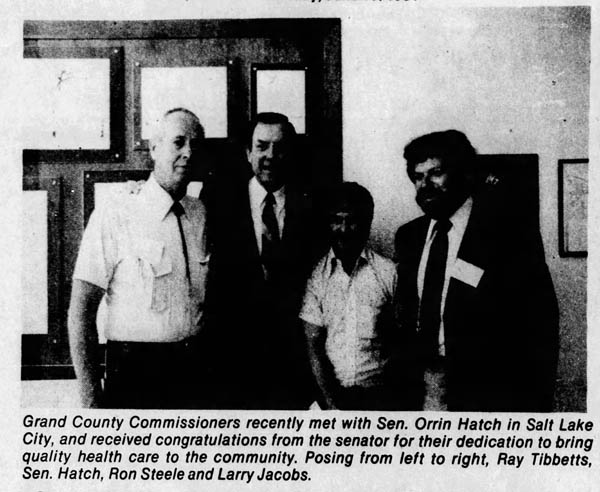

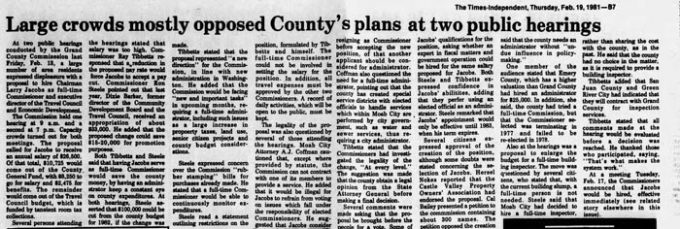

Prior to Stocks’ move, I had been seriously pissed when, in February of 1981, the three Grand County commissioners, Ron Steele, Ray Tibbetts, and Larry Jacobs, who had been in office only a couple of months, voted to name Jacobs to a full-time slot as county administrator, and director of both the Travel Council and Economic Development Board, at a handsome salary of $26,500 (For comparison’s sake, Kris’ house on Juan Court had cost $12,000 a few years earlier. My overpriced place on Westwood cost a princely $36,500 in 1980).

It was almost enough to make one run for office. There seemed to be a spate of attempts to create jobs for recently elected officials, when hundreds of people in town were losing theirs.

No Opinions (Yet)

I couldn’t yet express an opinion in the paper, as Sam didn’t offer me a column (a real plum in the newspaper biz) until December of that year, so I had no place to vent in print. As a reporter, I had to keep my opinions out of the paper’s news stories, which frequently was a struggle, but I believe, an absolute necessity. Reporting accurately would have to do, as I was, and am, a traditionalist when it comes to objectivity. It was my job in the news columns to inform, not convince.

In one story, printed in the Feb. 18, 1981 issue of The Times-Independent, I quoted extensively from a commissioners’ written release on the issue that was an absolute model of condescension, with a spice of arrogance. Here’s some of it: “Often times (sic) good leadership is not popular. It can approach the relationship one man or woman has with his employer or perhaps even that of a parent to a child. But, when factual data in any given situation is received and computed, then whatever role a man or men play, if his or their responsibility is to make a decision and implement it, then they cannot avoid that decision, nor can they succumb to the pressure of a few, when they must represent so many.”

They added, “We have been guilty of knowing all the facts and not adequately communicating them to the citizens before our decisions are made. However, is not that our responsibility? Can you not trust in our judgment to do what is in your best interest?”

And, “It will be of no use for us to continue trying to explain our intentions if you refuse to listen, or are unable to understand. For this we apologize. However, we must do our best while we hold office, and for this we do not apologize.”

Now, run along, little people.

I love this thing so much I have a framed, yellowing 40-year-old copy of the story to remind me of the joys of local journalism.

I wasn’t alone in my questioning; public comments in city council and county commission meetings were numerous and loud after each proposal. A citizen group actually filed a lawsuit against the commissioners, protesting their decision. At the same time, numerous attendees spoke in favor of both changes.

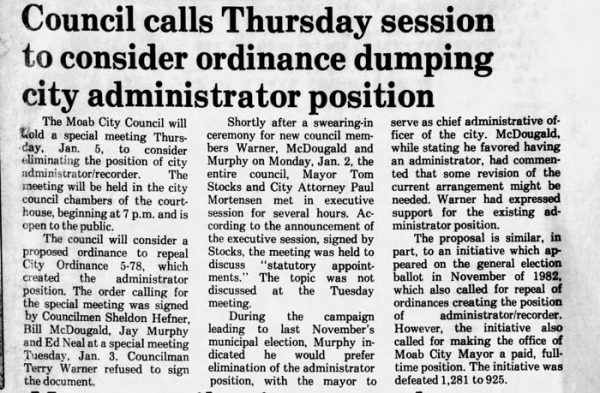

Tom wasn’t averse to a challenge, however. In late 1982, he and some supporters sponsored a ballot initiative calling for a change to a strong mayor format (at a salary of $25,000 this time) for Moab City. The measure went down to defeat 1,281-925.

One might think that would end it: The people had spoken. Au contraire, mes amies; Mayor Stocks was undaunted.

Happy New Year

Monday, January 2, 1984, was a legal holiday—so legal in fact, I actually had the day off. However, part of the off day was interrupted briefly when I was invited down to the courthouse to shoot a photo of the mayor swearing in new city council members Bill McDougald, Terry Warner, and Jay Murphy, which I thought was a bit weird, given it was scheduled for the New Year’s Day holiday, but then again, I had been around town long enough to expect governmental strangeness.

I was at home later, enjoying the peace, when I got a phone call from the dispatcher on duty at the sheriff’s office.

“I don’t know what it means,” he said, “but the mayor and all the council members just walked down the hall and went into the city council room. I thought you’d want to know.”

Would I ever; it pays to have a friend in the right place. I hustled back down to the city/county building, found the door to the city council chamber shut but not locked, opened it, walked in, sat down and pulled out my notebook. Whatever was under discussion came to a shocked halt.

“This is a closed meeting,” I was informed. “You can’t be here.”

I was ready for that one. I pulled out the card I carried with me everywhere for just such an occasion, and started listing the provisions of Utah’s open meeting statute:

A public body is required to provide public notice of

a meeting at least 24 hours before the meeting. The

public notice is required to:

• specify the date, time, and place of the meeting;

• include an agenda that specifies topics the public

body will consider;

• be posted at the location of the meeting; and

• be provided to a newspaper or local media

correspondent.

As far as I was aware, none of that had been done, especially the last bit; the only reason the “local media correspondent” knew about the meeting was the thoughtfulness of a county dispatcher, despite the fact that my number was listed in the phone book (Ask your grandparents).

In addition, I listed the limited reasons a meeting could be closed:

A public body may hold a closed meeting only for

certain reasons, including to discuss:

• a person’s character, competence, or health;

• pending or imminent litigation;

• certain matters regarding acquisition or sale of

real property, including water rights or shares;

• the deployment of security personnel, devices,

or systems;

• an investigation of alleged criminal conduct.

Changing the city’s form of government was not on the list, and no action could be taken (such as a vote) in a closed meeting, I advised them. The following morning, I found a notice for the meeting had been taped on the front door of the Times office sometime New Year’s Eve, possibly later, listing the topic of the meeting as “statutory appointments,” which was also not on the legislation’s list for permissible executive session topics.

Ejected

The council voted to toss me out anyway. I was tempted to force the issue by sitting in place until hauled off by the city cops, but figured that wouldn’t accomplish much, and would embarrass both the officers and me, as most of them were friends. If I had it to do over again, I would refuse to leave.

I remained out in the hall for the next several hours, attempting unsuccessfully to take photos of the mayor and council through a gap in the curtains covering the chamber’s glass walls. In addition, each time a council member left the room to use the john or get coffee, I would comment to each that the meeting likely violated the state’s open meeting law, and I intended to publicize it, to no avail.

The council held another special meeting, public this time, Thursday, Jan. 5, and dumped the city administrator/recorder position. Also during the meeting, Councilman McDougald said it was he who had requested the executive session held after the holiday swearing-in ceremony on Jan. 2.

Aside from the major change in city government, the meeting marked the end of my peaceful Thursdays. Special meetings of the council continued, on Jan. 19, Jan. 26, and Feb. 9 (*see below), all Thursdays, all connected with the change in government: terminating City Administrator Mark Hollowaty, naming the mayor chief administrator, and setting his annual salary.

Tom had finally gotten what he wanted.

I was critical of the change in my weekly Enough Rope columns, now that I had an opinion platform, including one printed Jan. 19, after Stocks issued an edict requiring any news releases from city departments be submitted to him “one business day” before being given to the media. He was apparently miffed that the building inspection and police departments had provided activity summaries from the previous year without his say-so, which had routinely been printed in the paper for many years.

The order immediately raised my First Amendment hackles: “This information is part of the public record,” I said in Enough Rope. “I would hate to see such raw data subject to an ‘executive interpretation’ before release. When I want to obtain a report, I generally try to ask the person with the most expertise, namely the department head.

“To provide reports to the administrative office before release implies that changes might be made,” the column continued. “Such a policy could also cause department heads to feel that they cannot speak freely or provide information to the media.”

Later, in my weekly rounds of city offices, I commented to department heads that the newspaper was not under the mayor’s control, and I would talk to whomever I damned well pleased, and I hoped they would continue to do the same. They did, bless ‘em.

Dumb Luck

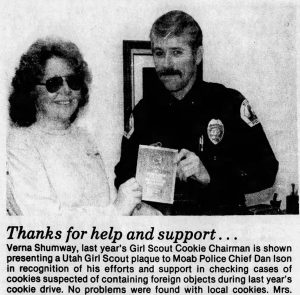

It was pure dumb luck that shortly after the paper came out, I happened to be in Police Chief Dan Ison’s office, chatting over cups of coffee, when Tom called to discuss the news release issue with him.

“Well, Bill’s right here,” I overheard Dan say, as both of us grinned, “and he’s talking about First Amendment rights and lawsuits, and that sort of stuff, so I think I’ve got to talk to him.”

Dan was an excellent chief.

So ended the press release brouhaha.

Open meetings, though, remained an issue. Basically, the statute said a quorum of the council could not meet without fulfilling all the requirements of the law: announcement, agenda, notifying the media, minutes, etc.

It got to the point that, after one late-night council meeting ended, I noticed all the councilpersons and the mayor huddled in the parking lot, so I walked into the middle of the group, took out my notebook and asked what was going on. They left.

It became an obsession of sorts: I even started attending the council’s budget workshops, which were horribly boring and seldom resulted in a newspaper story, but it was, by gum, a meeting with a city council forum. I was fried from meetings, both city and county.

Oddly enough, throughout this and other controversies, Tom and I maintained an interesting relationship. Despite our disagreements, I bent over backward to keep my opinions out of news stories, limiting them to the column, and found I could still get interviews with the mayor anytime with a single phone call.

In an even more unusual development, a year or two after I left Moab, I read a story where Tom complained about local media coverage, saying that journalists were showing up for only a short time during council gatherings, when, during previous years (I’m paraphrasing), “someone was here who used to stay through all the meetings.”

I realized with a start he was talking about me. Well, go figure.

It was obvious that, for a number of years, a majority of voters didn’t share my concerns about the form of city government, as Tom was re-elected three more times, serving until 1998, long after I had departed town.

The issue didn’t die, however. In 1994, the city council voted to return to the strong council/weak mayor format. In March of 1996, seven local residents submitted a petition asking for a voter referendum to reverse that decision and again return to the strong mayor system, with an additional provision giving the mayor the power to veto any council-approved rules or regulations. Zots.

There apparently had also been a war of advertisements in local print media. Stocks paid to have ads run in The Advertiser criticizing City Manager Donna Metzler, which were followed by council-sponsored ads supporting her.

Here’s the kicker: According to an article in The T-I, during a March 26 council meeting, “Stocks questioned how all five council members could participate in writing an ad discussing city business without officially calling a council meeting, implying that the council had violated Utah’s open meeting laws.”

My goodness.

Stocks didn’t run for re-election, and the proposed referendum didn’t appear on the November, 1997, ballot, so the city’s strong council arrangement remained, and Moab’s first woman mayor, Karla Hancock, replaced him in January of 1998.

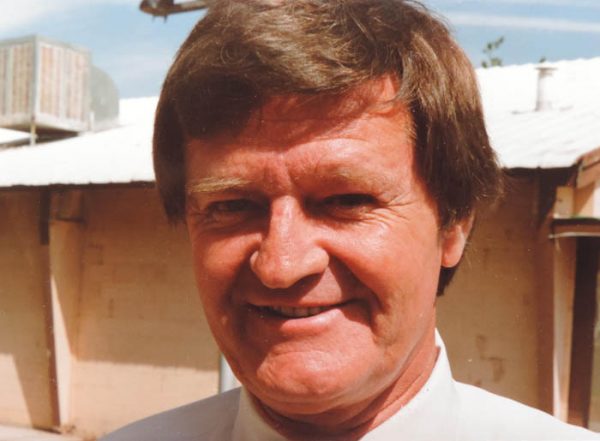

Tom and his wife Gay moved to LaVerkin, Utah, population about 3,000 at that time, where he was (surprise!) elected mayor of the tiny community. Following a single term, he moved to North Las Vegas, where he was not elected mayor, but was active in several local organizations. He died there of a heart attack Sept. 3, 2011, at the age of 78.

It was quite a run.

*Fred in the Trunk

Thursday, Feb. 9 (my former unwinding day) proved to be blindingly busy, for a reason beyond the city council hearing on the mayor’s salary, set to begin at 8 p.m. that evening: Toward the end of a stultifying and painfully long county commission meeting that had begun at 10 a.m. that morning, I was listening to my pocket scanner through an earpiece, trying to stay awake, hoping I could grab dinner before the evening city meeting, which also promised to be lengthy.

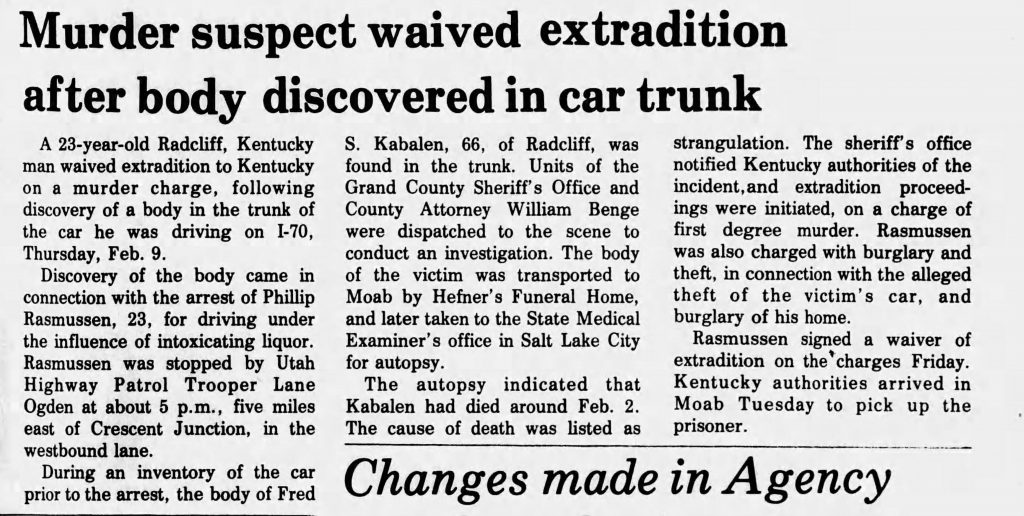

At a little after 5 p.m. a call came in from Utah Highway Patrol Trooper Lane Ogden, five miles east of Crescent Junction on I-70, saying he had discovered the body of a murder victim in the trunk of a car during a traffic stop.

Talk about an instant wakeup call.

I jumped up, camera bag in hand, and ran toward the door (Looking back at my previous columns, I guess I did that a lot). The commissioners stopped whatever they were discussing.

“Hey, where’re you going?” one hollered.

“Murder victim out on the interstate!” I said over my shoulder.

“Come back and tell us about it!” I love small towns.

I made the best time I could northbound on Highway 191. Now, to understand what followed, you need to understand it was February, and cold, bloody cold. And I was driving an air-cooled VW convertible with no back window. In addition, I was using an early-model Canon A-1.

It was a lovely camera, but was one of the first that was totally electronic. In other words, all functions, including the shutter, were battery dependent. Most cameras could fire the shutter, even if the light meter battery was dead—not that Canon. Without power, it was an inert, if expensive, lump.

Shivering as I drove, I popped the batteries from the camera and flash unit, (five total) under my arm and into, well, my crotch, trying to keep them warm enough to function. Another factor: it was already really, really dark—no moon and no stars. After an illegal U-turn across the interstate’s divider, I got out near Lane’s unit on the westbound side. I couldn’t see much; my penlight’s glow was a weak, sickly yellow.

I interviewed Lane quickly, using his flashlight to illuminate my notebook. He explained he had pulled over the car, which had been weaving, as a possible DUI. After he handcuffed the driver, he began filling out the standard impaired driving questionnaire. Routine.

His investigation revealed the driver was a 23-year-old Radcliffe, Kentucky man, who appeared to be pretty heavily bombed. Lane continued with his usual questions: Where are you coming from? Where are you going? And what proved to be the biggie:

“Anyone else in the car?”

“Just Fred,” the kid responded, “he’s in the trunk.”

Lane checked. Sure enough, Fred was in there, wrapped in a bedsheet, naked as a jaybird, and four days’ dead.

“I was grateful he warned me,” Lane said. “If I had opened the trunk and found a dead body, I would have had a heart attack.”

The suspect told Lane he had been employed at Fred’s wrecking yard in Louisville, Kentucky, when the victim allegedly made homosexual advances toward him. In response, the suspect apparently strangled Fred, and stuffed the body into the trunk of the victim’s car.

The kid then headed west in Fred’s car to, I kid you not, bury the victim in a particular location near Grass Valley, Calif. Upon hearing that, I suspected he might not have been the sharpest knife in the drawer.

Here he was, in the Green River Desert, where there was room to bury Napoleon’s army, but no, it was Grass Valley or bust, so bust it was, thanks to Lane’s sharp eye. The suspect later waived extradition, and was picked up in short order by Kentucky authorities on a murder charge.

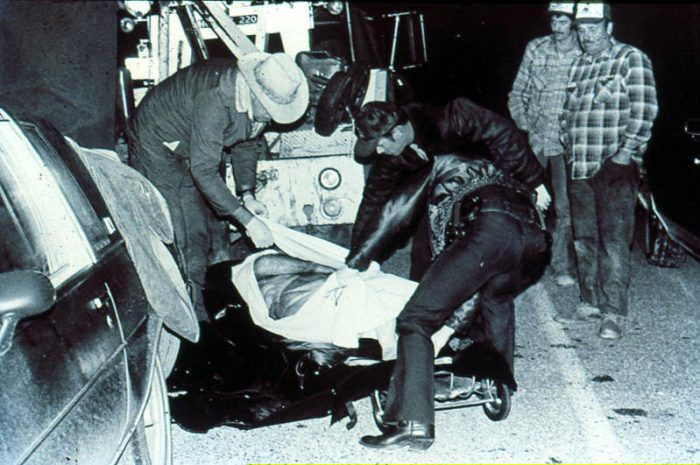

County Attorney Bill Benge, along with Grand County deputies Stan Goodman and Steve Brownell, and funeral home director (and City Councilman) Sheldon Hefner arrived on the scene shortly after Lane made the arrest, and shortly before I showed up.

I got set up to take a shot, when the batteries in my penlight, used to help me get the distance right in this era before autofocus, expired. I could hear Goodman, Brownell, and Hefner grunting and wrestling with the body, but could still see nothing, as none of them were using a flashlight.

I focused the camera on the taillight of a wrecker parked behind them, the only source of light at the scene, then moved the lens’ focus ring what I thought would be the right distance for the stretcher I couldn’t see, but knew was between me and the car. I figured I would wait until I heard the zipper of the body bag, so the result would be publishable in a family newspaper (not violating what we used to call “The Breakfast Standard”: “Photos in the newspaper should not cause readers to throw up their morning cornflakes.”).

Knowing I likely would get only one shot before the batteries in my camera and flash also died (which they did, along with my spares), I heard the zipper and fired. That was it: one shot and I was out of business—a 74-mile roundtrip for one photograph.

In the darkroom the following day, I discovered I had been a wee bit early in my timing. The photo was, amazingly, in focus and properly exposed, but so was part of Fred, who was lumpy after four days in the car, the time required to drive from Kentucky to the middle of Nowhere, Utah.

After grabbing my one shot, I returned to Moab and the remainder of the county commission meeting (They were still at it), where I filled the commissioners in on what had occurred, checked the minutes to make sure they hadn’t done anything weird while I was gone, and prepared for the city council hearing, set to begin a short time later. I no longer remember whether I got any dinner—probably not.

That was Thursday.

After all that effort, I was determined the photo should run in the paper—preferably on the front page, above the fold, where potentially award-winning news photos were usually printed. I figured I would probably get yelled at by some readers, but what the heck.

On production day, however, Boss Sam Taylor didn’t see it that way. I think he would have preferred the photo just disappear, but I lobbied for its publication; I was proud of that shot. Sam finally agreed to print it, but buried Fred (so to speak) on page B-1.

Afterword: Poor, lumpy Fred ended up as a slide in a PowerPoint presentation I used for several years in my college photojournalism class as an example of bad ethical decision-making. The photograph, I told my students, had been printed for all the wrong reasons: Conditions were difficult, I had driven a long way, frozen my butt off, and with only one chance, still gotten a clear image in the dark.

“But was it right?” I would ask them.

No.

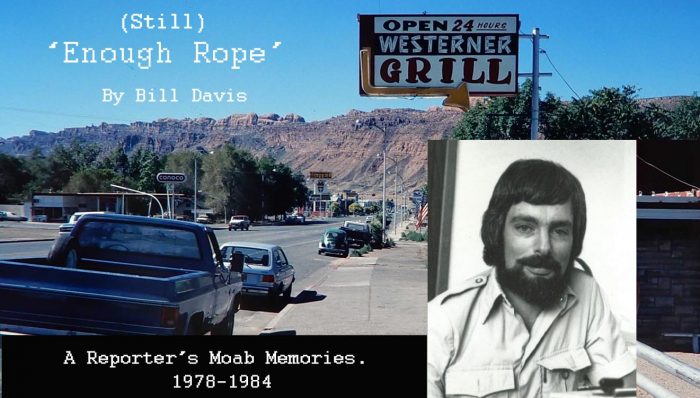

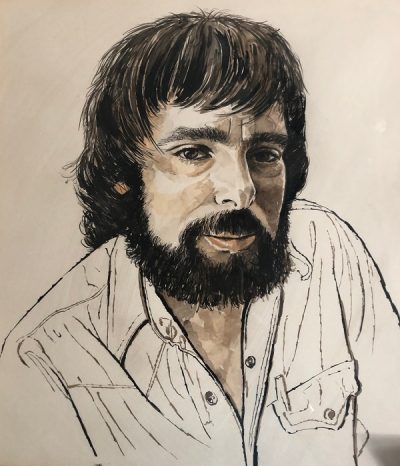

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!