It has become common among people who have the good fortune of being both affluent and self-aware to be ashamed of their pain. After all, what could possibly justify feelings of depression or anxiety among those of us who live materially comfortable lives when the mere survival of a significant portion of the globe’s population remains precarious?

Sometimes this shame is expressed as self-deprecation, as when Louis C.K. suggests, “We have White People Problems in America. You know what that is? That’s when your life is amazing, so you just make stuff up to get worried about.” Other times, it takes the form of eruptions of obviously misplaced anger. I’m thinking here of “Karens” and “Kens” demanding to “speak to the manager,” and the spectacular, unhinged performances of air rage that seem to make the news with regularity these days. (And it isn’t particularly hard to think of still darker examples.)

The psychosocial turmoil that seems to pervade modern life has also been frequent fodder for serious artistic exploration, as in Mad Men or The Swimmer. To be sure, artists have mined themes like decadence and ennui for a very long time and yet it seems safe to assert that this has become more thematically interesting terrain in our age of widespread affluence. It seems similarly safe to assert that the social scientific consideration of these topics — for example in the form of academic research or psychotherapeutic treatment — is also a relatively recent development.

My personal curiosity about this bundle of topics has recently led me to reconsider the work of Christopher Lasch. Many of his insights were prescient when published forty years ago and have rarely been extended or improved upon since. Here are three insights from my reading that strike me as particularly relevant to the moment:

Consumerism is more complicated than it may appear.

It is exceedingly easy to lament consumer culture and not much more difficult to superficially detach oneself from its worst impulses. (I do it all the time.) A feeling of moralizing disgust is a natural response to the recognition that we often, in the phrasing of George Carlin and Tyler Durden, buy things we don’t need with money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like.

But, for Lasch, consumerism cannot be neatly severed for criticism from the “larger pattern of dependence, disorientation, and loss of control” that defines industrialism writ large. He points out that industrialism reordered not just consumption but also production in specific ways that promote dependence, passivity, and alienation.

Scientific management and the institutionalized division of labor drew boundaries between mental work and manual labor, between design and execution, between manager and worker, and between producer and consumer.

This observation has two important implications. First, it is a reminder to take critical care when considering just one side of the production-consumption coin without also considering the other. The resocialization of the self-sufficient citizen as a pliant consumer happened at the same time and on a parallel track with the resocialization of the craftsperson as “human capital.” Second, the splitting of the individual’s identity between two selves, one a consumer and the other a producer, is almost certain to have disjunctive, disorienting effects on the individual and ultimately on society.

Psychosocial crisis may be an inevitable response to conditions in which the potential for mass death is a constant presence.

One of the deep paradoxes of modern existence is that, at the same time as violence has practically disappeared, the annihilation of the whole human race has never been more plausible. World War II, and in particular the Holocaust and the dawning of the nuclear age at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, introduced industrialized death on a scale that verges on incomprehensibility.

One consequence of this new reality is that the rhetoric of crisis has become pervasive, applied not just to threats like nuclear war or ecological catastrophe, but also to everyday political questions and personal challenges. For Lasch, the prevalence of a “propaganda of disaster” creates a state of chronic anxiety in the population.

The looming potential of mass extinction also introduces a sort of supremacy of the victim. Here, it is worth laying out Lasch’s thinking in some detail.

Lasch notes that, in ways unknown to prior generations, modern humankind is burdened with the “knowledge that otherwise rational men will carry out the extermination of entire populations if it suits their purpose and that many good citizens…when confronted with these acts, will accept them as an eminently sensible means…”

This type of beyond-category immorality defies common conceptions of crime and punishment with respect to its perpetrators. At the same time, it raises to new extremes both the randomness and severity of consequence that separates victim from survivor. We, in effect, “think of ourselves as both survivors and victims or potential victims.”

In such a context, the survivor-victim naturally enjoys an elevated moral place in society and this new hierarchy has just as naturally led to social competition oriented around victimhood. But Lasch notes a further paradox:

“The experience of victimization, which justifies resistance, can also destroy the capacity for resistance by destroying the sense of personal responsibility. This is precisely the deepest injury inflicted by victimization: one finally learns to confront life not as a moral agent but solely as a passive victim, and political protest degenerates into a whine of self-pity.”

Lasch’s analysis helps us make sense of the evolution of the performative protest and the emergence of the “crybully.” Far from idealizing the transcendence of victimization, we now appear to be trapped in a political economy in which victimhood is its primary currency.

A Culture of Narcissism is a Culture of Survivalism and a Culture of Survivalism is not pretty.

In The Minimal Self, Lasch goes to great lengths to distinguish his meaning of “narcissism” from its common usage as a synonym of “selfishness.” He notes that the Greek legend is oriented not around egoism but rather a fundamental confusion between the self and the not-self. The narcissistic self is a self uncertain of its own contours and of the contours of the real world in which it exists.

It isn’t hard to see how this kind of narcissistic confusion has become endemic and extreme at a time when even our most basic understanding of what is real is heavily mediated by fantastic, mass-produced images. We know, for example, that there were many protests/riots across America last year in the wake of George Floyd’s death. And yet who among us really knows what these events were?

As Lasch lays it out, this narcissistic confusion leads naturally, if unfortunately, to a defensive contraction of the self into a sort of siege mentality, which ultimately leaks or explodes outward from the individual in a number of forms: “our protective irony and emotional disengagement, our reluctance to make long term commitments, our powerlessness and sense of victimization, our fascination with extreme situations and with the possibility of applying their lessons to everyday life, (and) our perception of large-scale organizations as systems of total control.”

It sounds a lot like modern America to me.

Stacy Young is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in Southwest Utah.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

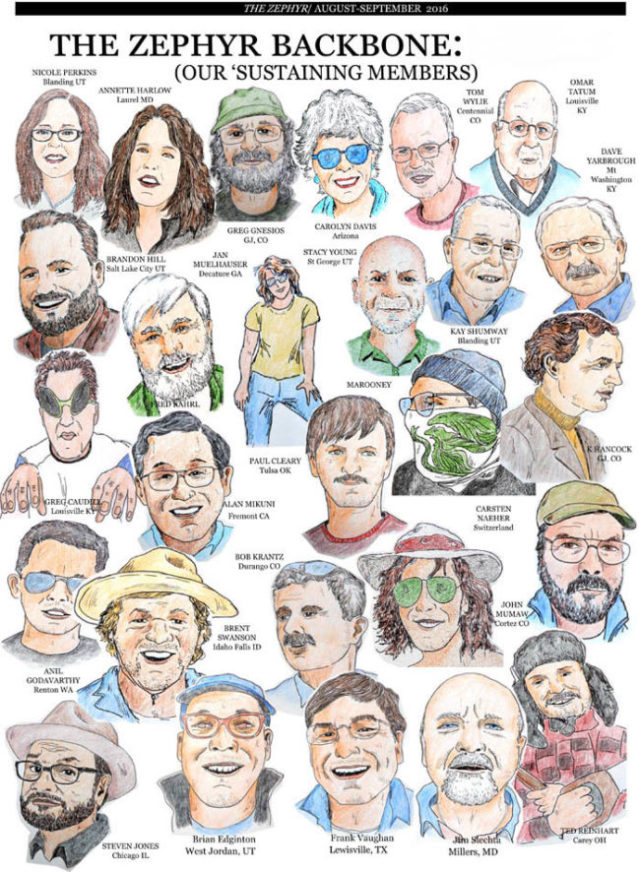

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!