Note: A much shorter version of this article first appeared in the June/July issue. After that piece was published, I was contacted by the granddaughters of Charles Boothroyd and the surviving daughter of Jeannette Sullivan. The information that Carolyn Boothroyd, Linda Boothroyd Lazaroff, and Jeanne Nabozny were able to provide about that tragic event as well as the history of their families, both before and after the shooting, convinced me that I needed to return to the story. This dramatically expanded account is dedicated to them. JS

JULY 7, 1961 10:30 PM MDT.

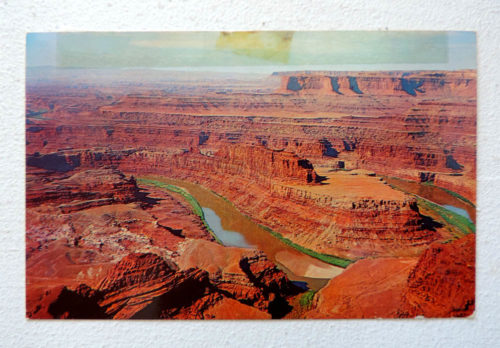

NEAR CRESCENT JUNCTION, UTAH

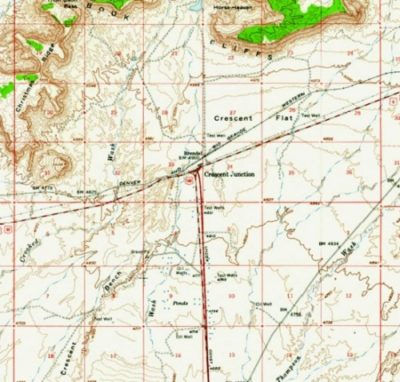

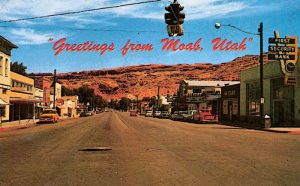

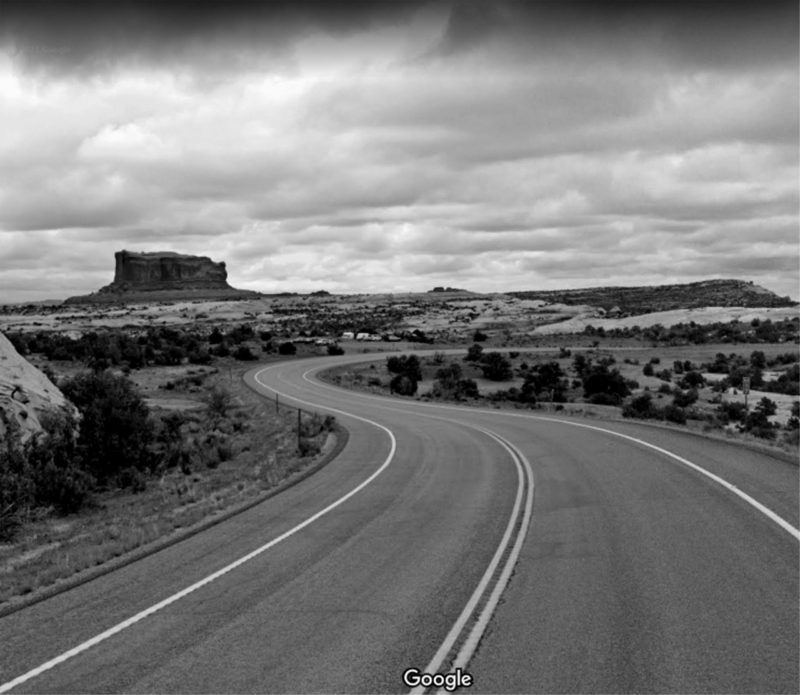

In mid-summer, the days stay long in the high desert badlands of southeast Utah. On July 7, 1961, sunset came officially at 8:45 PM. But on this evening, the sun’s fading rays lingered long after sunset. Near Crescent Junction, thirty miles north of Moab, streaks of crimson clouds hung stubbornly along the western skyline for another hour, far beyond the dark silhouettes of the Island in the Sky plateau, and Dead Horse Point, where all this madness had begun just 72 hours earlier. The heat lingered as well. At sunset, the thermometer still hovered near 90 degrees.

To reach the Junction from the south, travelers used old US Highway 160; the paved road climbed out of the Moab Valley and wound its way north between 2000 foot canyon walls, wrapped precariously around the edge of Dead Man’s Curve, until it finally emerged from the deep shadows and onto the barren, moonscaped badlands.

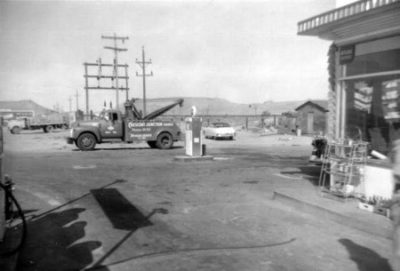

As the road approached its intersection with the major east/west highway US 6/50, the land was flat and featureless and almost uninhabited. The last five miles were straight as an arrow. But at Crescent Junction, a small gas station/cafe’, established in 1947 by Ed and Erma Wimmer, was like an oasis of sorts—one of the few points of civilization between Grand Junction, Colorado and Price, Utah. Travelers were especially impressed with the cook and Al Lange’s pie-making skills.

From that lonely intersection, the views were almost limitless—from Grand Mesa in Colorado to the east, to the Henry Mountains and the Aquarius Plateau far to the west, and south to the Blue Mountains and beyond, the amount of country one could gaze upon, in one sweep of the horizon, is staggering. On this evening, an hour past sundown, the afterglow from all these distant features was almost surreal; it seemed as if the light was emanating from the mesas and monuments and mountain peaks themselves—as if they had a life of their own.

But the beauty on this particular night was deceiving. Somewhere out there, amidst the lovely, lonely vastness of the empty land, dark, unspeakable secrets and inexplicable horrors laid buried in them. Silent and bewildering.

Two FBI agents, called down from Salt Lake City and asked to assist in this ever deepening and bewildering tragedy, had just left the sheriff’s office in Moab and were unsure of their next move. They pulled to the side of US 160, just north of town, and stopped to stretch their legs and consider the situation. Both men climbed out of their black sedan and leaned against the rear bumper of their vehicle. Special Agents (SA) Taylor and Jones lit cigarettes and drew deeply from them. There was still just enough lingering ambient light to see the smoke dissipate as they exhaled.

But it was past 10 PM. Soon it would be pitch black, except for the brilliance of the Milky Way. The waning moon wouldn’t rise for another four hours. For two men from the big city, the star field was impressive. They watched the skies, the fading light on the towering cliffs above Moab and on the darkening La Sal mountains and tablelands that surrounded them. The two agents talked quietly between themselves. They complained about the repressive heat. They marveled at the stars in the desert night. They had both noticed the magnificent fruit orchards that Moab was known for. But the idle conversation was just a momentary diversion. Mostly, they thought about the girl. Where was she? Where was Dennise Sullivan?

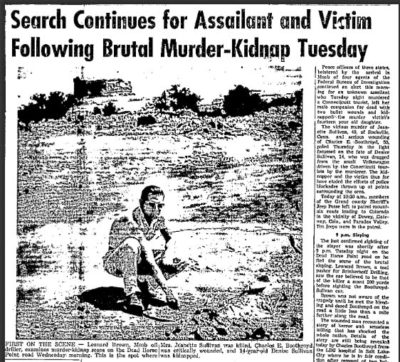

The agents had officially joined the investigation on Wednesday evening. Now, as Friday came to a close, they, along with dozens of law enforcement officers and search and rescue volunteers, were frustrated. They had little hard information to go on. Facts were sparse. Speculation was rampant. It was the lack of any real movement in the investigation that had convinced Grand County’s Sheriff John Stocks that he needed federal assistance.

In fact, the sheriff had called the FBI office in Salt Lake City within hours of the incident, but Special Agent in Charge (SAC) Leonard Blaylock explained that the Bureau could not officially enter the case in the first 24 hours unless a ransom had been demanded or there was proof that the kidnapper had crossed state lines. On that bleak Wednesday morning, hours after this brutal nightmare began, Stocks was at a loss to offer much of anything in the way of hard evidence…he didn’t even know who the kidnapper was, or where he had taken the girl.

Still, assuming this case would not be resolved quickly, Blaylock sent four agents to Moab to assist in any way they could. By early afternoon, the FBI was actively, if not officially, offering whatever skills and strategies their agency could provide.

Feeling overwhelmed in this new, unfamiliar terrain, the two agents stared at the vast landscape before them and thought of proverbial needles in countless haystacks. But this wasn’t a needle they were looking for. It was a terrified 90 pound, five foot tall, 15 year old girl, who had seen her mother executed, right in front of her, along a lonely stretch of dirt and gravel road—the Dead Horse Point Road. It had all happened in a matter of seconds, for reasons no one could begin to explain. Why? They stared blankly into the night.

The FBI men occasionally saw lights blink on and off in the far distance, amid the mesas and canyons and rugged escarpments that composed this torturous landscape. One agent nodded to the other, noting the lights. They both sighed. The volunteers were still looking, they presumed. Good people. They really want to find that girl.

Just past 10 PM, the agents received a call from SAC Blaylock. Another tip had been received by their office and Blaylock asked them to check it out. Someone reported a “suspicious vehicle” camped along a remote dry creek bed called Salaterus Wash, some 40 miles northeast of Moab. The drainage joined Pinto Wash, southwest of Cisco and eventually made its way to the Colorado River. It sounded like another wild-goose chase, but both agents were running on adrenaline and eager to pursue any clue, no matter how far-fetched, if it might take them to the girl.

Blaylock provided them with detailed directions and urged them to move as quickly as they could. Time was running out. SA Taylor started the government sedan and pointed north on US 160. To reach Salaterus Wash, they would need to drive 30 miles north, to Crescent Junction and the intersection with US 6/50, and then drive east another 30 miles to Cisco. From there, they might need wings. The terrain was that rough and they wondered if their two-wheel drive government sedan would be able to negotiate the sandy, rocky, rutted jeep tracks and mining roads that led to their intended destination.

As they topped out of Moab Canyon, past Dead Man’s Bend and onto the high plateau above Moab, they saw another light in the distance. But this was different. It wasn’t a southbound vehicle on US160. This set of lights was coming from the west, from Seven Mile Canyon, to their left, and moving rapidly. In fact, it was the very road where this nightmare had begun—the road to Dead Horse Point. Still they shrugged; it was probably another member of the Moab Jeep Posse headed back to Moab, or even one of the local deputies. Or maybe just another tourist. Still, their attention was drawn to the lights. They hoped for any new clue, any break in the case.

Since the extraordinary events of Tuesday evening, the Fourth of July of all days, law enforcement had worked the case with little new information, but they weren’t totally bereft of it. After the killer fired a .22 rifle slug into the back of Jeanette Sullivan’s head, he turned to her male companion and shot two more rounds, point blank, into his face as well. The man fell to the dirt and gravel and the killer presumably took the girl. The shooter surely assumed he’d left two dead bodies by the side of the road, assuring no witnesses to his bewildering crimes. But he was wrong. Charles Boothroyd was still alive.

The impact knocked Boothroyd to the ground and he momentarily lost consciousness, but not only had he inexplicably survived, he remembered everything. Every horrid detail. An hour after the shootings, he was able to give the sheriff an accurate description of the killer’s vehicle and a moment-by-moment account of the deadly encounter. He remembered the license plate’s state and prefix. He and Jeanette had even spoken to the man earlier as they’d watched the sunset together from the Point. And Boothroyd recalled something else. He said the man’s name sounded like “Oregon.”

But now, three days later, no one had seen the car or the girl or the suspect. They had vanished. Law enforcement officers waited for a break. The community of Moab was devastated. Its citizens were desperate for news and asked, again and again, the one question everyone wanted an answer to: Have they found her yet?

The agents slowed their vehicle as the headlights drew closer to the intersection. It appeared to be a passenger car. The sedan turned left in front of them and gained speed on US 160, headed north. The two agents stared at the car, just a couple hundred yards ahead. They both glanced at their notes. Yes. The car precisely matched the description that Boothroyd had provided the sheriff—a 1955 Ford sedan. The color matched as well. They looked at each other, almost doubting their own eyes…Is this possible? As the agents drew closer, the license plate number came into view.

Taylor looked at his notes again. It was a Utah plate. The prefix matched. They could make out a”CJ”in their headlights. A Carbon County, Utah license plate. Still closer, they could read all of it: “CJ6626.”

My God, they gasped. This is the man we’ve been searching for.

One of the agents called in the sighting to Blaylock who immediately contacted the Grand County Sheriff by 2-way radio and requested backup. They decided to wait until they reached the Crescent Junction intersection to make the stop. For now, they maintained a safe distance. Did the man in the car realize he was being followed? That he had been spotted and identified? They would soon find out. Finally, within a few hundred yards of the T-intersection, the agents activated the emergency overhead red light and pulled up tight on the suspect’s rear bumper. The vehicle began to slow down. They were just south of the Crescent Junction store and gas station. The Utah Highway Patrol had been maintaining a presence here since Tuesday night, not long after the first bulletin was posted.

Finally, the suspect vehicle began to pull toward the shoulder. The brake lights came on. They were approaching the stop sign and US 6/50. Both cars stopped in a swirl of dust, but as the agents climbed out of their car, they could see the man roll up his window and lock the doors. Across the street, at the gas station, two young men were working the night shift, Ronald Engstrom and Bucky Taylor. The station owner, Pat Wimmer, saw the commotion and the red lights and the three men stepped outside for a better view. They wondered if this was the guy everyone had been searching for.

One of the agents approached cautiously; the other remained in the vehicle with the radio. SA Jones came to the driver’s side window and called out to the man. “We are FBI. Please step out of the car.” The driver said nothing.

The agent shouted again, “We are FBI!” The man, now clearly agitated, yelled, “Show me some ID!”

The agent asked through the closed window, “Are you Abel Aragon?” and reached for his badge. He heard the man yell, “Prove it!”

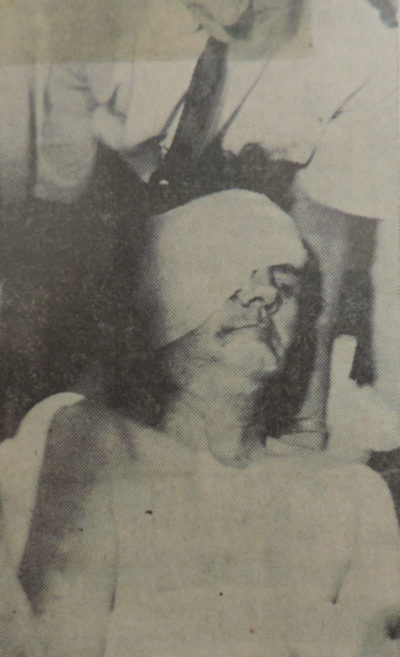

Then the agent saw him turn to his right and reach for an object on the passenger seat. The agent, in that split second, must have seen what was about to happen, and reached inside his jacket for his service revolver. But it was too late. The interior of the car flashed brilliantly in the darkness. SA Jones recoiled and, briefly, the gunflash blinded him. In the next instant his vision returned and he peered inside the sedan,weapon drawn. The man, Abel Aragon of Price, Utah, had shot himself once in the head, just behind and above his right ear, with a .22 caliber pistol. The bullet exited the left side of his head, smashed into the door frame, and tumbled to the floor. He slumped in his seat, blood gushing from the head wound onto the seat cushions. He was already unconscious.

One of the agents ran toward the store and told the boys to call an ambulance. The other agent grabbed the microphone for the 2-way radio and called again for assistance. Pat Wimmer, the owner of the Crescent Jct. store was also deputized by the sheriff; he sprinted to Aragon’s passenger door and broke out the window with a tire iron. More than anything, they wanted to get into the trunk of that sedan. Wimmer reached past Aragon’s motionless body for the car keys. He fumbled at first but finally retrieved them from the ignition and tossed them to the agent. Now, looking for the right key in the darkness, the agent raced to the trunk.

Please…please let us find this girl, and let her be alive.

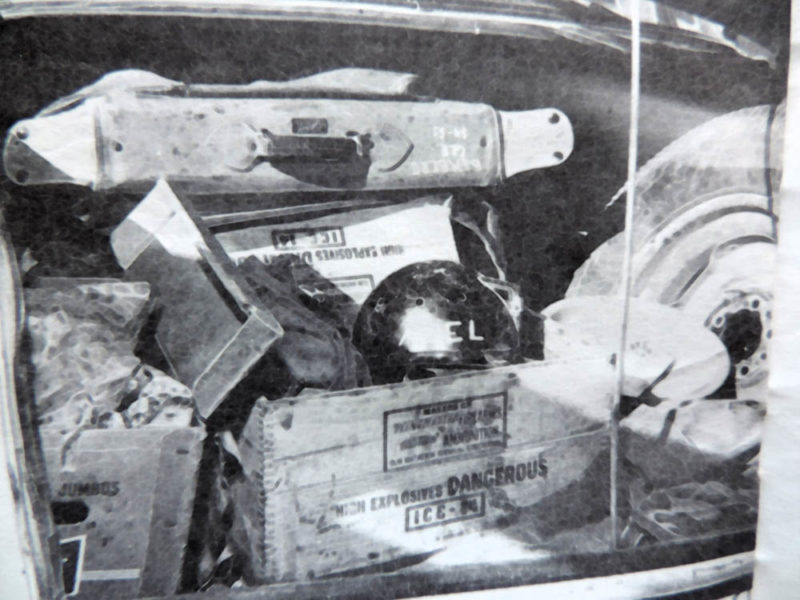

The agent turned the key and opened the trunk. It was full of camping gear and mining equipment, loaded into wooden Winchester ammunition boxes. An old military B4 bag was thrown across the top of the pile. They looked more closely, beneath the stash of clutter. There was nobody there.

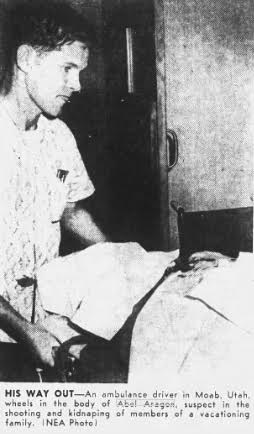

Both agents and Wimmer waited for Sheriff John Stocks and the ambulance to arrive. It took less than 30 minutes. Stocks took charge of the vehicle. The sheriff checked the front bumper of Aragon’s car. It was dented and scuffed, as if it had recently rammed another vehicle. This has got to be him, Stocks thought. He looked at the man, now drifting toward death and apparently taking with him secrets and motives and actions that no one else could begin to understand. They tried desperately to talk to Aragon, but he was unresponsive. The ambulance arrived, driven by Norman Miner, and he and John Stocks moved Aragon to a gurney and raced to the hospital. Dr. Jay Munsey was the physician on duty that night. The ambulance crew rushed Aragon into the surgical area and Munsey examined the wound. At 12:11 AM the doctor stepped out of the room and advised the sheriff that the situation was hopeless. There was nothing anyone could do for the man. Finally, at 12:25 AM, two hours after he put the gun to his head, and three days after the killings, Abel Aragon died.

Where was Dennise Sullivan?

ABEL ARAGON: “A TRUE AMERICAN HERO”

No one can know if a man who puts a pistol to his own head ever hears the shot that kills him. Is there a split second when the sound of the blast precedes the eternal blackness that comes next? For Abel Aragon, it might have been the last gunfire he would ever hear, but it certainly wasn’t the first. Abel Aragon was familiar with weaponry and the taking of lives and the horrors of violence and death. But until just past 9 PM on Tuesday evening, July 4, 1961, no one would have ever thought to call him a murderer. Abel “Benny” Aragon was an American Hero. He was admired and respected by his friends, loved and cherished by his wife and children, and honored by his country.

He was born in Colorado in 1926 but grew up in Carbon County, Utah, a hundred and fifty miles west. Price, Utah lay in the heart of coal country. Like most young men in the area, Aragon began working in the mines when he was barely a teenager. He started out as a “rope rider” and was employed by the High Heat Coal Company. According to one retired miner, “rope riders did the most dangerous work in the mines, balancing precariously on the hitches between coal cars as they wound through darkened tunnels. When the cars were full, the rope rider would signal that it was time to return to the surface. All the while he would balance himself between the two cars, each carrying a ton and a half of coal when full.”

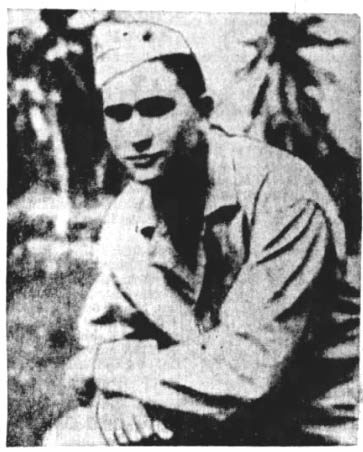

From an early age, Benny Aragon lived with and even expected risk and danger. When the war started he joined the Marines. According to his draft card, Aragon was born on July 29, 1924. But in fact, he had fudged his age when he enlisted; otherwise he would have been too young to sign up. Like so many young men of his generation and in that critical time, the desire to “serve his country” pushed Aragon to do whatever it took to join the fight. His actual birth date was July 6, 1926.

Many of his hometown buddies joined him, including his friend Chuck Semken. Within a year, he and Semken were sent to the Pacific and saw action in one brutal battle after another against the Japanese army. It is difficult to explain or understand the kind of courage Aragon repeatedly demonstrated. It has been argued that there is a fine line between bravery and madness; in the savage fighting that Aragon experienced in the Pacific, that line was almost impossible to find.

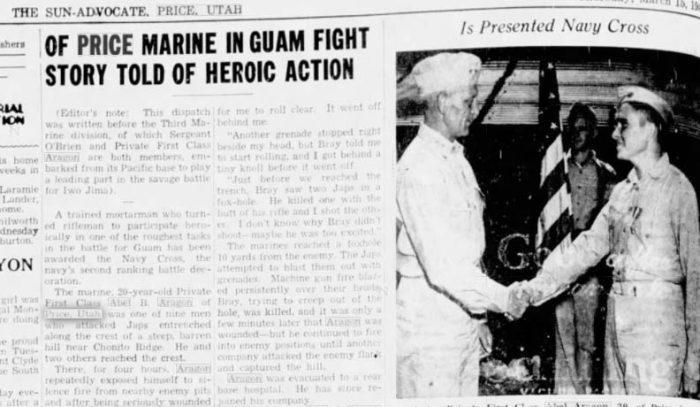

Few of his friends and loved ones back in Utah had any idea what he and his fellow soldiers were enduring, as they fought their way across a vast ocean, one island at a time, pushing always toward Tokyo and an end to the war. But on March 15, 1945, an article appeared in the Carbon County weekly newspaper, the Sun Advocate. Here are portions of that story, as it was reported 75 years ago…

(Sun-Advocate Editor’s note: This dispatch was written before the Third Marine division, of which Sergeant O’Brien and Private First Class Aragon are both members, embarked from its Pacific base to play a leading part in the savage battle for Iwo Jima).

A trained mortarman who turned rifleman to participate heroically in one of the roughest tasks in the battle for Guam has been awarded the Navy Cross, the navy’s second ranking battle decoration. The marine, 20-year-old Private First Class Abel B. Aragon of Price, Utah, was one of nine men who attacked Japs entrenched along the crest of a steep, barren hill near Chonito Ridge. He and two others reached the crest.

There, for four hours, Aragon repeatedly exposed himself to sniper fire from nearby enemy pits and after being seriously wounded in the left hip, went without medical aid for two hours while continuing to fire on the enemy. Aragon participated in two attacks on the enemy position. Enemy machine guns opened fire on the first wave of attackers when they moved within 10 yards of the crest, and the marines were forced to find cover in a small gully in the center of the slope.

Nine men made the second attack. Only Aragon, Sergeant Charles Bomar of Houston, Texas, and Corporal Buel W. Bray of Ada, Oklahoma reached the crest. Bray died there.

“The Japs rolled grenades down on us when we got near the top,” Aragon said: I don’t know where Bomar went but Bray and I cut across the hill toward an abandoned foxhole. We were crawling on our hands and knees toward an abandoned foxhole. We were crawling on our hands and knees to avoid machine gun fire and a grenade would have exploded under my chest, but Bray warned me in time for me to roll clear. It went off behind me.

“Another grenade stopped right beside my head, but Bray told me to start rolling, and I got behind a tiny knoll before it went off.

Just before we reached the trench, Bray saw two Japs in a fox-hole. He killed one with the butt of his rifle and I shot the other. I don’t know why Bray didn’t shoot–maybe he was too excited.”

The marines reached a foxhole 10 yards from the enemy. The Japs attempted to blast them out with grenades. Machine gun fire blazed persistently over their heads. Bray, trying to creep out of the hole, was killed, and it was only a few minutes later that Aragon was wounded–but he continued to fire into enemy positions until another company attacked the enemy flank and captured the hill.

Aragon was evacuated to a rear base hospital. He has since rejoined his company.

Aragon, son of Abel J. Aragon of Price, was a “rope rider” on a coal conveyor for the Uta-Carbon Coal company, Rains, Utah, before enlisting.

The Navy Cross Citation read:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Private First Class Abel Bidal Aragon (MCSN: 867254), United States Marine Corps Reserve, for extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty while serving with the 60-mm. section of Company A, First Battalion, Third Marines, THIRD Marine Division, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Guam, Marianas Islands, 22 July 1944. Assuming the duties of a rifleman in a nine-man group assigned the mission of assaulting a strongly-held enemy ridge, Private First Class Aragon proceeded up the ridge and succeeded in reaching this crest despite withering hostile fire which reduced his group to three men. During the next four hours on the ridge, he repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire and, on several occasions, succeeded in silencing the fire from near-by Japanese pits. Although sustaining severe wounds in the left hip in one attempt, he continued to fire upon the hostile position for two hours. By his cool courage, fortitude and devotion to duty, Private First Class Aragon upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

*** *** ***

Aragon survived Guam and went on to see combat in (and survive) Iwo Jima. Like millions of other young American men, Aragon was preparing for the invasion of the main islands of Japan as the summer of 1945 drew to a close. But then came the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the sudden end of World War II. After years of brutal combat and incessant scenes of horror and death, Aragon was honorably discharged in December 1945 and suddenly, he was home. Also returning to Carbon County, Utah was his friend Chuck Semken, who had served in the Marines as well and like his pal Benny, had somehow managed to survive the war.

By late spring, both were back at work. Semken went to work for the Price River Coal company, though eventually Semken chose a life in law enforcement and would become a Carbon County deputy sheriff. Mining was still the dangerous occupation that Aragon had left behind in 1942, but now, after Guam and Chonito Ridge and Iwo Jima, nothing seemed as hazardous. On June 15, 1946, he married his high school sweetheart, Eva Escondon. They began to raise a family and would eventually have five children.

Aragon was liked and respected by the community. His children were well-behaved. He was conscientious to a fault. No one could find a harsh word for Benny Aragon. Life seemed good.

On July 19, 1957, three miners were killed when deadly gases escaped from old tunnels owned by the Independent Coal and Coke Co. in Castle Gate. The men died despite the heroic efforts of rescuers who reached the victims shortly after the accident occurred. The men had been working in the Number 2 mine when a “bounce,” or a “shifting of the earth,” released the gases. Air seals in the old mines exploded and carbon monoxide gas rushed through the breached seals. Rescuers succeeded in leading a fourth miner, Mike Milovich, to safety, but one of them, Harold Wilstead, succumbed to the leaking gases and later died. Though he wasn’t given credit in later press stories, Milovich would remember, years later, that it was Abel Aragon who had also been there to assist him.

*** *** ***

But in the early 1960s, the coal industry in Utah began to suffer. The World War had been a boon to coal, but except for a brief bump from the Korean conflict, the demand for coal declined steadily through the 1950s as the nation’s energy demands were met by cleaner and cheaper options, especially natural gas. Layoffs became a growing concern for the county’s economy. Benny Aragon had been laid off briefly in the summer of 1960, but had been called back. Finally, in February 1961, the curtain came down. There just wasn’t enough work to keep him on the payroll. The “reduction in force” felt permanent this time. Suddenly the war hero was unemployed.

Aragon found odd jobs, but not enough to survive. He applied for and received unemployment compensation with the Utah Employment Security Office, but he was now trying to provide for his family on a fraction of his coal miner earnings. In the spring, Aragon grew desperate. He traveled to Moab on several occasions looking for a job in the uranium mines. At one point, probably in June, Aragon met and was befriended by Loren and Genevieve Johnson who lived in a modest home at the far south end of Moab. They had a small peach orchard and Genevieve offered to let Benny camp there. Years later, their daughter Gemie Martin, would recall that brief time in a poignant entry from an online public journal she kept…

“When I was seven years old, my parents let an unemployed man named Abel Aragon, from Price Utah, camp out in our peach orchard. Mr. Aragon, a decorated WWII veteran, was looking for work in Moab, Utah where we lived. According to Mama, he was somewhat disgruntled that he had sacrificed for his country, but was unable to find the employment necessary to support his family after he returned. Mama seemed under the impression that he had some mental problems which she attributed to his war experiences. I am not sure how my parents became acquainted with Mr. Aragon, but they felt sorry for him and did not feel he posed any danger to their family.”

Neither of her parents thought he was a risk, but both could see how troubled the man was. Gemie’s brother Bud noticed the man as well, and on a couple mornings, shared his donuts with him. Aragon seemed grateful.

Years later, when Genevieve Johnson died in 2011, her friends remembered her generous soul. They wrote, “As a gentle and kind-hearted soul, she was truly a champion of the underdog. Her needs were always last on her list of priorities, while her wants most often involved filling someone else’s needs.”

She may have been the last person to show that kind of compassion for a man who was clearly coming apart.

Abel Aragon’s 15th wedding anniversary had been June 15, but he wasn’t able to celebrate it with his wife in the manner he had wanted. He was nearly broke. On July 1, Aragon believed he had secured work at a uranium mine, and even contacted his priest, John LaBranche, in Price, Utah, to tell him of the good news. But the offer fell through. No one knows why.

On the Fourth of July, 1961, away from home, and the picnics with family and friends, and the celebrations of the day, Abel Aragon chose to spend his time alone, in what was then one of the most remote sections of Grand County, the state of Utah, and the American Southwest. In the late morning Aragon made his way north out of Moab Canyon on US 160, to the turn at Seven Mile Canyon. In those days, the road was narrow and winding and treacherous in places. It probably took more than an hour to reach the overlook at Dead Horse Point.

It was another hot day, though not as scorching as the days to come. The temperature in Moab only reached 91 degrees on July 4. Thunderstorms in the late afternoon were as erratic and unpredictable as ever. Moab registered .14 inches for the day. Other parts of the canyon country were drenched; others saw not a drop.

With those kinds of dramatic thunderstorms brewing across the canyonlands, the skies at Dead Horse Point must have been spectacular that afternoon. Aragon sat near the edge of the 2000 foot cliffs and watched the light change over the next few hours. He must have found himself thinking of his past, of his great accomplishments in the war, of his own belief that he was a good man, and wondering how everything could have gone so bad so quickly. Then it occurred to him–this was July 4. His birthday, July 6, was in two days. He would be 35 years old. What did he have to show for all his years of hard work?

Aragon was out there, on the edge, alone for most of the day. Occasional tourists, who came and went during the afternoon, visited with him briefly and left. Cliff and Wilma Aldridge, from Moab, had decided to drive out to the Lookout that afternoon. They saw the man, by himself, and they made no effort to say hello. Wilma, for some reason, noticed his shoes. They were worn out at the heel and the man seemed to limp when he walked. She recalled that he looked to be in pain. But within an hour of sunset, the Aldridges walked back to their car and headed back to town. As they were leaving the area, they passed a small foreign car coming in.

It was a Volkswagen Beetle, with Connecticut license plates. An older gentleman with wire rim glasses stepped out of the driver’s seat. At his side was a woman, perhaps in her late 30s. A young girl, a teenager, climbed out of the back and ran to the overlook to see the view. The threesome noticed the man sitting by himself and waved hell. Benny Aragon walked over to Charles Boothroyd and introduced himself.

Boothroyd smiled and shook his hand, but thought, “What a strange name. I never knew anyone named ‘Oregon.’”

CHARLES BOOTHROYD:

A RESILIENT FAMILY, ENDURING TRAGEDIES…HOPEFUL FOR THE FUTURE

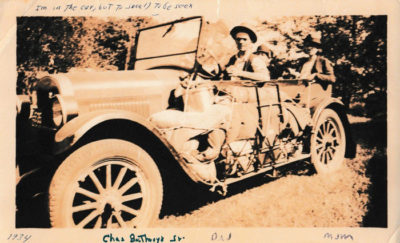

For more than a decade, the Boothroyd Family had endured one tragic loss after another. In some ways, death and hardship had marked the lives of Charles and Dorothy since the early days of their marriage. Dorothy Pihl and Charles Boothroyd grew up in Connecticut and married in 1926, when Dorothy was just 17. Times were hard and though the family history is vague, Charles traveled the country, sometimes by riding the rails with other men searching for a job. Charles was away when the couple’s first child, Charles Ernest, was born in 1929.

But in 1932, his luck, workwise, changed for the better. While a quarter of the American workforce found itself unemployed, Charles landed a job as a grinder with the Merrow Machine Company in Hartford, Connecticut. Merrow produced an excellent line of sewing machines, whose origins dated back to the early 19th Century and has flourished to this day. It was solid work, and paid a decent wage—Boothroyd would stay with Merrow for the next 40 years. That spring, the Boothroyds’ second son was born, Albert Ellsworth, and for a time, life for the Boothroyds seemed to be on an even keel. The country was still trying to climb its way out of the worst economic times in its history, but with a solid job and healthy sons, the Boothroyds felt blessed.

Two years later, on April 29, 1934, Dorothy gave birth to twins, August Theodore and Axel Frederick. But within minutes, it was clear to the doctors and to the family that both boys had been born with insurmountable health issues. August died just two days later; Axel hung on for a week. Their deaths were devastating to Dorothy and Charles, but the Boothroyd family showed the kind of quiet courage and resilience that was necessary to survive in the hard times of the Great Depression. Two years later, Lillian Irene came into the world, their first and only daughter. It must have been a particularly frightening time for Dorothy and Charles, just two years after they lost the twins, but Lillian was a healthy baby. The family breathed a sigh of relief.

Charles Boothroyd presented the appearance of a quiet, mild-mannered man. He wore wire-rimmed glasses and spoke quietly to his friends and family. But beneath or despite his physical attributes, Charles contained multitudes. He was a wanderer and an adventurer and something of a loner. His search for solitude sometimes annoyed his family and friends, who thought he needed to stay closer to home. But it’s who he was. He loved to travel and camp out under the stars, and get lost in the desert. He was a disarming trickster and a teaser and sometimes had a playful sense of humor that often surprised new friends.

Boothroyd’s wanderlust was a necessary talent at times. During the Depression, young American men “rode the rails” across the continent in search of work and Boothroyd Family lore suggests that Charles was one of them before he settled into a career with Merrow. Stories that he may have gone to Texas and “got into some kind of trouble,” in which he may have been arrested and then released, were all part of his colorful but mysterious and rumored past.

Even as a family man, Charles shared his love for the outdoors with his wife and children. During the 1930s they took to the backroads and often camped out. He would load their old convertible sideboards with camping gear and head for the woods. When World War II arrived, Charles and Dorothy were most likely relieved that both of their sons were too young to serve. In the early 1940s, Charles decided to purchase a farm near Strafford,Vermont, but knew he would need the attention and muscle of his two sons. In 1946, young Charles (Charlie to family and friends) lied about his age and tried to enlist in the Navy, but he was discovered by officials and sent home. Eventually his mother reluctantly signed the papers and Charles left home. He served with the Navy and saw service overseas aboard the USS Stribling, in post-war Europe.

Without Charlie to help with the work, his father found it increasingly difficult to run the farm himself. In addition, the farm was in many ways a primitive vestige of 19th Century life. The home lacked electricity or indoor plumbing. A small brook actually ran to the house and water was accessed from it. Dorothy, always the supportive wife to her husband’s dreams, endured the hard life as long as she could, but after just ten months, he realized the folly in his efforts to live there. Reluctantly, Charles placed the farm on the market and the family returned to Rockville.

By July 1950, young Charlie had returned from the service and quickly planned to marry his sweetheart, Grace Dimmock. They were both determined to build a life of their own, away from the farm. But the wedding ceremony was performed under a cloud of sadness. Just weeks before the wedding, Gracie’s little brother, Walter, had been helping out at the farm with his father, Grace’s dad. While trying to move a massive boulder from a field, the huge granite rock rolled over and crushed Walter. He was killed instantly. He was only 16 years old. More tragedy was to come.

*** *** ***

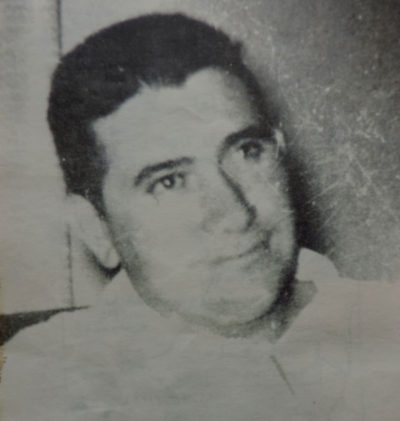

While Charlie was in the Navy, his younger brother Albert, three years his junior, contemplated his own future. Albert revered his older brother and wanted to serve his country as well. But he was cursed with terrible eyesight. A childhood friend later recalled that his buddies sometimes called him “Einstein.” His thick eyeglasses gave him a professorial look. But despite his poor vision, Albert regularly played baseball at the nearby sandlot and “never had a disparaging word for anybody.” When he turned 17 and again with his mother’s permission, Albert tried to enlist in the Navy, like his brother, but was rejected, specifically for his eyes. Undeterred, Albert turned to the U.S. Army; his medical records indicated that his vision in both eyes was 20/400. And he was colorblind to boot. But incredibly, he was accepted.

As young Charlie prepared to return home from the Navy, Albert was inducted into the Army. It was Spring 1949. His timing could not have been more tragic. Within a year, the United States found itself at war again, this time in Korea. The history of the Korean conflict and the events that led to its outbreak is long and complicated. But in June 1950, the North Korean Army attacked its southern counterpart, pushing across the 38th Parallel. They drove the South Korean Army to the southern tip of the peninsula. The United States and South Korean military forces in Korea were caught off guard and months passed before a United Nations resolution and a strongly reinforced Army successfully pushed the North Korean army back across the 38th. A brilliant military maneuver by General MacArthur’s army at Inchon seemed to assure a victory for the South. MacArthur confidently predicted a “home by Christmas” strategy for his weary American soldiers. Among those soldiers was Private Albert Boothroyd.

But the course of the war was about to change dramatically. Almost half a million soldiers of the Chinese Army were massing along its boundary with North Korea at the Yalu River. The United States assumed their actions were part of a defensive strategy, but on November 25, 1950, the Chinese Army, augmented by the surviving elements of the North Korean Army, swarmed across the Yalu, stunned US forces and sent them fleeing south. It was one of the most chaotic and humiliating routes of the United States Army in its history.

The young recruit Albert Boothroyd was a part of the Headquarters and Service Battery, 38th Field Artillery Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division. His unit was trying to escape to the south as the Chinese and North Koreans cut off their flank. They constructed one obstacle after another to slow or halt the retreat of the American soldiers. The 38th was hoping to make its way from Kunu-ri, where they had first been overwhelmed, to what they hoped would be temporary shelter and safety at Sunch’on. But, on November 30, Albert’s unit, and many others, were cut off. Against overwhelming odds, their position was overrun. Thousands of Americans died in the hectic battle and over 2000 American soldiers were captured. Albert Boothroyd was one of them.

Though the Boothroyd Family followed news reports of the Chinese onslaught and knew Albert was somewhere in that battle zone, they were not notified until December 24, 1950—Christmas Eve—by Western Union telegram, that he had played an active role in the fight. They were informed that Albert was officially listed as “Missing in Action (MIA).”

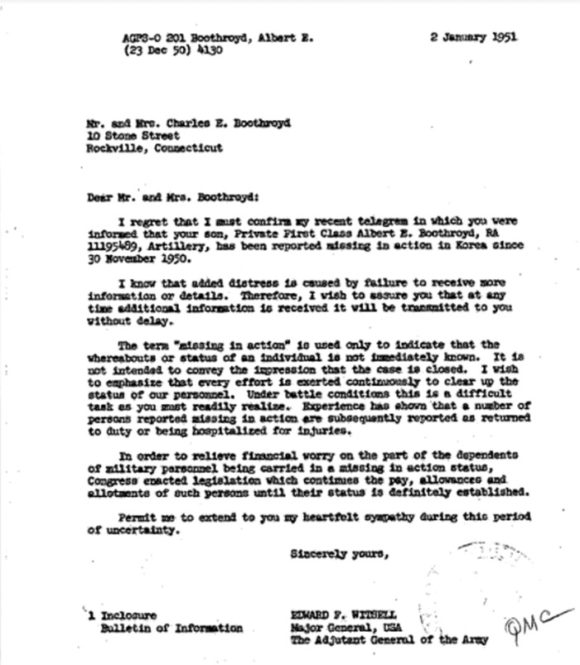

On January 2, 1951, Charles and Dorothy received a follow up letter from Major General Edward P. Wittsell, Adjutant General, who wrote in part:

“I regret that I must confirm my recent telegram in which you were informed that your son, Pvt Albert E. Boothroyd, has been reported missing in action in Korea since November 30, 1950… I know that added distress is caused by failure to receive more information or details. Therefore I wish to assure you that at any time additional information is received, it will be transmitted to you without delay.”

In February, a Chinese propaganda press release included Albert Boothroyd as a Prisoner of War. As painful as the news was, it must have at least given the family hope that Albert was alive. They waited for more news. Nothing came.

For two and a half years, Albert’s fate remained unknown. Stories of horrific North Korean POW camps and the brutal, deadly conditions that the Americans were forced to endure, reached the American military and media by mid-1951. Credible rumors of “death camps” where hundreds of American POWs had died, under extraordinarily cruel conditions, offered little comfort to families like the Boothroyds. Year after year, the Boothroyds waited for word, for some kind of closure on Albert’s fate. Finally, in August 1953, the news they had dreaded arrived by telegram. The next week, a letter arrived. It said in part:

I am writing this letter to confirm my recent telegram in which you were notified that the Communist forces in Korea have reported that your son, Corporal Albert E. Boothroyd, died while in their custody…General Ridgway, Chief of Staff of the Army, and I fully realize the deep sorrow that such a report brings to the loved ones of our gallant soldiers, and we want you to know that you have our deepest sympathy.

It was signed by Major General William E. Bergin, Army Adjutant General.

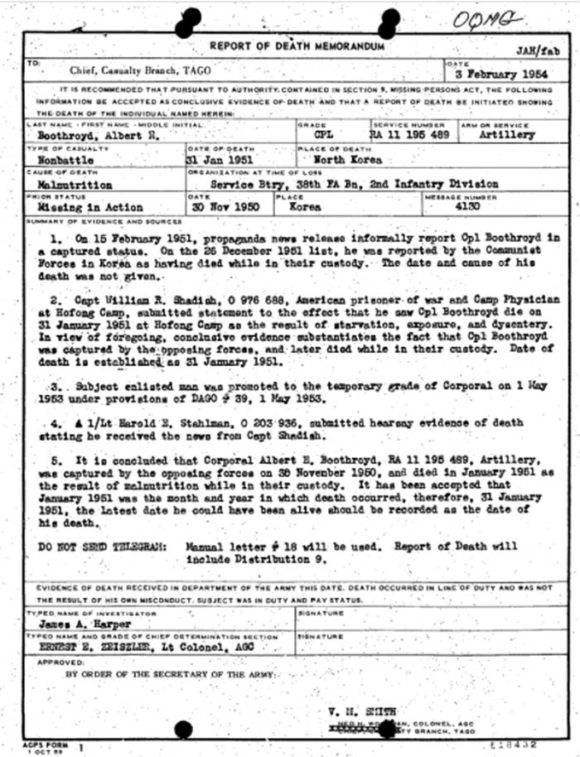

Not until the following February did the family receive any details of Albert’s death. Information was finally provided via Capt William Shadish, a physician who had also been a POW at the camp and had been able to offer a few details. A US Army “Report of Death Memorandum,” dated February 4, 1954, stated:

Capt William R. Shadish, 0 976 688, American prisoner of war and Camp Physician at Hofong Camp, submitted a statement to the effect that he saw Cpl Boothroyd die on 31 January 1951 at Hofong Camp as the result of starvation, exposure, and dysentery. In view of foregoing, conclusive evidence substantiates the fact that Cpl Boothroyd was captured by the opposing forces, and later died while in their custody. Date of death is established as 31 January 1951.

It was over. His remains were never recovered. The family never truly recovered either.

During those long years of waiting for news of Albert, his brother Charlie’s wife Gracie gave birth to two daughters, Linda and Carolyn. From their very earliest memories, they would hear stories of their uncle and his ordeal and death in Korea. It was a sorrow that ran so deeply in the Boothroyd family, it almost felt like an emotion they had been born with. For Dorothy, the loss of her son was more than devastating, and most likely accounted for her rapid physical decline throughout the 1950s. For years, she had been worn down by the debilitating effects of arthritis. Now she developed serious heart issues. Later, her granddaughters could rarely recall a time when she left their second story apartment in Rockville. Her health continued to deteriorate.

For Charles, his only relief from the tragedies and hard times that continued to haunt him and his family came when he could hit the road and get away. His occasional trips, often alone and for weeks at a time, caused hard feelings within the family. Some thought he was shirking his responsibilities and that he was insensitive to his wife’s growing needs. But Dorothy seemed to understand Charles better than the rest; at the very least, she accepted the fact that he needed these trips away from home as much as he needed food and water.

Charles made at least three trips during the mid-50s, and his destination was almost always the American Southwest. There was something about the desert that appealed to him, that seemed to fortify his spirit and restore his soul. He found the peace and solitude that he was so desperately searching for. Once he traveled West with a nephew, but later regretted making the invitation. The nephew didn’t share Charles’ love of the landscape and “listened to the radio all the time.” In 1956, he devised a car top carrier on the roof of his sedan that did double duty as a storage area and, at night, as a sort of crude but functional canvas tent. He liked being off the ground and away from the scorpions and snakes. He always came back from his trips refreshed and renewed.

But after 1956, his trips stopped. Dorothy’s health spiraled downward. She was mostly confined to her bed, as the rheumatoid arthritis that had been attacking her body for years took its toll. But she remained the kind and gentle mother and grandmother and wife that she had always been. She was adored by the family for her sweetness and admired for her quiet courage. On March 6, 1959, Dorothy Boothroyd died of a coronary thrombosis. She was just three days shy of her 50th birthday.

Charles Boothroyd, after 33 years of marriage, found himself a widower. He and Dorothy had endured unspeakable losses over the past three decades. Now, at 53 years old and perhaps feeling old for the first time in his life, he wondered what lay ahead. He continued to work at Merrow Machine Company in Hartford, and always looked forward to spending time with his children and grandchildren.

He and Dorothy had attended St. John’s Church in Rockville for years, though recently, because of Dorothy’s health, he had often attended alone. He continued to attend the Sunday service after her death. One day, he noticed a woman in a nearby pew. She was with two children, whom he assumed were her daughters. The oldest appeared to be in her early teens; the younger girl no more than three or four. The mother, perhaps in her late 30s, caught Charles’ attention, and after the service he approached them and introduced himself. The woman smiled and shook his hand. Her name was Jeannette Sullivan, she said. And she introduced her two daughters. Jeanne was just three. The older daughter, now on the brink of teenhood, smiled sad hello to Charles. Her name was Dennise Sullivan. None of them could have imagined where the future would take them. At that moment, however, it felt like the beginning of something. It felt like hope.

JEANNETTE SULLIVAN…A Woman Ahead of her Time.

And DENNISE, a Bright Life Ahead

Jeannette Sullivan was like a woman from the future who never had the chance to see it. Throughout her life, she carried an independent spirit and a candor that made her unique for the times she lived through.

She was born Jeannette Beaver, the identical twin of her sister Grace. Her father, William George Beaver had met their mother, Grace Eleanor Martin, during the Great War (WWI). The twins were born at Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island in October 1919. But while the family was visiting relatives in Pennsylvania, young Grace suddenly became ill and died of diphtheria. She was buried in the Aristis, Pennsylvania cemetery. The sudden death of young Grace shook the Beaver family to its core. Now little Jeanette, the surviving and only child of William and Grace, became all the more precious to them. And naturally they felt more protective as well.

Will Beaver was a career military man and had seen active duty in World War I as a Master Sergeant with the 64th Coast Artillery. He and Grace and little Jeannette lived at military bases across the United States and overseas as well. Among those outposts, he had tours of duty in Panama and Hawaii. Beaver was stationed at Ft. Stafford in Honolulu when he and Grace made the decision to end his military career.

After William Beaver retired from the Army, they decided to relocate to Rhode Island where they had once lived and loved. They built a home for themselves and their daughter near Portsmouth, Rhode Island on West Main Road. In those days, West Main Road was a quiet lane and extended far into the countryside. The family was surrounded by some of the most beautiful farms in Rhode Island.

When they finally moved in, during the summer of 1933. Jeannette was just 14 and though their new home was somewhat remote — Portsmouth was on the island of Aquidneck — Jeannette loved everything about it. There were no schools in Portsmouth then, so she took public transit to attend school in nearby Newport.

Jeannette thrived in her new and now permanent home. But her mother still worried about their relative isolation and even created a new Girl Scout Troop in Portsmouth so that Jeannette could have that kind of experience. Here Jeannette developed her love for the outdoors and her sense of adventure.

As she grew, her artistic and musical talents were often on display via school events and publications. She excelled at athletics — gymnastics, and the high dive were her specialties. Whatever challenge was put before Jeannette Beaver, she conquered. Everyone who met her was impressed. Years later she would even obtain her pilot’s license. There was nothing Jeannette Sullivan couldn’t do.

In the 1930s, nearby Newport, Rhode Island was one of the richest and most celebrated seaside resort towns in the country. Some of America’s wealthiest families often summered there. The Astors, the Vanderbilts, and the Widener family all maintained extravagant vacation homes in Newport. Jacquelyn Bouvier, later The First Lady, spent many of her summers on the island.

While the Beaver Family lacked the types of credentials that are measured in dollars and cents, William and Grace made their own kind of special impression on the community. Will joined the Portsmouth American Legion Post and ultimately served as its post commander. They were both highly regarded for their integrity and commitment to public service. Jeannette, the young daughter of the retired military man, took the Newport “social set” by storm. What Jeannette lacked in family fortunes, she made up for via the sheer will and shine of her beauty and personality. Not only did she often attend the lavish “Governor’s Balls” on Aquidneck Island, she danced with the governor. When the morning newspapers included a photograph of the event, there was Jeannette, beaming broadly.

As war approached in the early 1940s, Commander Beaver took an active role via the Legion in helping to provide for the comfort and well-being of the growing army that would soon be headed overseas. Newspaper articles from 1942 mention numerous social events staged by the Legion Post for young men about to see active duty. Will even urged young women, including his daughter for sure, to participate in these dances and ‘stage canteens.’

During the war, Jeannette married her first husband, but it felt like a mistake from the beginning and they soon divorced. Eventually, she would marry her first husband’s good friend, Dennis Sullivan. During the war, Dennis served in the Navy at the Newport Operations Base & Depot. He worked as a mechanic, but off duty Sullivan was a musician. He often played at local clubs and bars and it was here that he met Jeannette.

They married in 1945 and Dennise was born a year later, in May 1946. But this marriage was more turbulent than the first. Sullivan had a drinking problem and could be physically abusive to Jeannette. Nor was he a reliable bread winner for his wife and daughter. When he did work, Dennis occasionally managed to find something that was music-related, but usually he found himself picking up wages in factories or garages, utilizing his mechanical skills. But he didn’t seem to enjoy that kind of work, and taking care of his family often took a backseat to his work preferences.

To Jeannette Sullivan, he was a failure, both as a father and a husband, but they stayed together for more than a decade. At some point, they relocated to Rockville, Connecticut and in 1956, Jeanne was born. But Jeannette Sullivan would only endure so much abuse. Finally, she went to a lawyer. She was fiercely independent and determined to protect her children, even when it meant divorce. Jeannette Sullivan had been willing to face whatever uncertainties lay ahead, no matter the sacrifice.

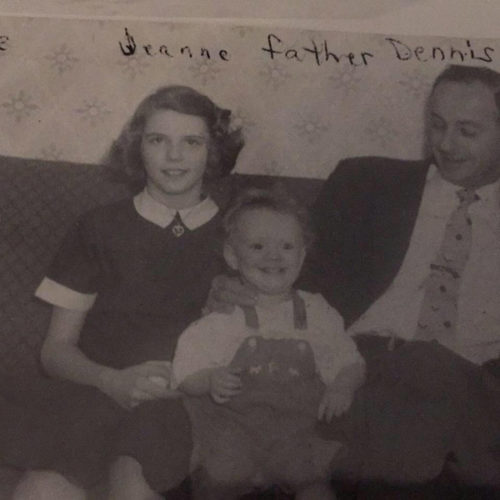

One faded family photo shows Dennis with his two girls. By 1958, he had reportedly moved to California, taken a common law wife, and left Jeannette on her own, financially and emotionally, to raise Dennise and Jeanne. It was a constant struggle. (Dennis would return to Connecticut briefly, three years later, but not for long.)

But Jeannette was an excellent seamstress, surely taught by her mother, and she was able to get work at Three Sons Dry Cleaning in Rockville, Connecticut. Some government assistance was available for child support for her two girls. Jeannette was also an extremely gifted artist. She had won a blue ribbon in a recent local art exhibit. Jeannette dreamed that perhaps she might find a way to make a living at it. But she always worried about next week’s bills. She had no idea what the future held.

She and her daughters had discovered and joined the St. John’s Episcopal Church in Rockville and it was there that she met Charles Boothroyd. The recently widowed man and the divorced mother of two somehow connected. He liked her spirit and her passion for life; she admired and appreciated Boothroyd’s kindness and honesty. He actually seemed… responsible. More than anything, he adored her daughters and that meant the world to her. Soon they were seeing each other regularly and, finally, Charles brought Jeannette and the girls to meet his family. There was some awkwardness and even some resentment that Charles was devoting so much time to this new relationship. But the Boothroyds could see how happy Charles was. After such a rough decade, they could only wish them well.

Christmas 1960 was a happy time for Jeannette Sullivan and her two daughters, and for Charles Boothroyd. Just two years earlier, their lives had been worn down by years of heartache and loss. Now, a year after Jeannette and Charles met, their relationship had blossomed; they even spoke of marriage at some point in the future. At one point he asked Jeannette what she wanted for Christmas. Jeannette wiggled her ring finger and said, “Maybe something to put on this hand.” Charles promptly went out and bought her a pair of gloves. She was beginning to appreciate his surprisingly irreverent sense of humor. But Charles didn’t take the suggestion lightly.

Charles had also bonded with Dennise and Jeanne. Neither had known what it meant to have a caring and involved father. Now they were calling him “Daddy Charles.” The affection was reciprocal. Dennise was becoming more of a “teenager” with each passing week and now she and boy, Harry Hansen, had taken an interest in each other. Jeannette was concerned—she thought Dennise was too young to already be thinking of boys, but then she remembered her own teen years and reluctantly accepted whatever came next. It helped as well that Harry was Charles’ nephew. If the boy got out of hand, she had Charles to lend support. He felt more and more like a father again. It was like a new beginning for them. The future looked bright.

“THE TRIP OF A LIFETIME”

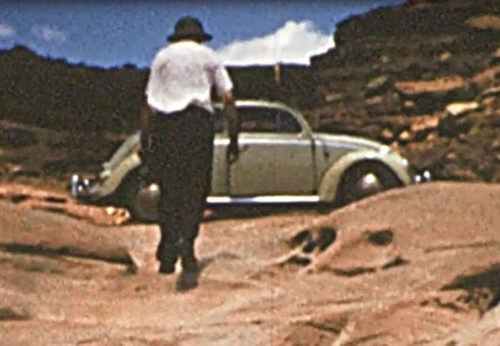

Over the last year, Charles had often shared his enthusiasm and love for the American West with Jeannette and the girls, and had regaled them with stories of his adventures. They would sit, wide-eyed and enthralled, as he painted images for them of this vast desert landscape that he had loved for so many years. Now, after a five year absence, he was ready to head West again. He had recently purchased a new sage-green Volkswagen Beetle and was in the process of equipping it for his next long journey. Now it occurred to him—why not take them along?

He mentioned the idea to Jeanette, who was instantly enthusiastic. Her daughter Dennise was thrilled. Dennise had never been west of New England and she loved the idea of traveling by car, all the way to the mountains and canyons of Colorado and Utah. She said it would be “the trip of a lifetime.” But to provide some incentive, Charles and Jeannette told her that the trip would be contingent on her school performance. If Dennise achieved the kind of good grades that they both knew she was capable of, the trip would be her reward. Dennise eagerly agreed. Throughout the Spring, Dennise excelled at her studies and by May, it was decided— the trip was on. They even set a departure date: they would leave Rockville on June 30, 1961.

They poured over maps and road atlases and picked an itinerary. They would go west through Pennsylvania and Ohio, then over the Mississippi River and across the Great Plains to the Rocky Mountains. He wanted them to see the canyonlands of southeast Utah and then ultimately travel north to Wyoming and the Yellowstone country.

There was even talk of marriage. This was 1961 and the idea of an unmarried couple traveling around the United States in those days raised a few eyebrows within the Boothroyd and Beaver Families. What would people think? It certainly seemed “inappropriate” and there was the question of their respective ages. Charles, at 55, was almost 15 years Jeannette’s senior. Further, Dorothy had only died two years earlier. Was it too soon?

But the promise that they might ‘tie the knot’ during their two week vacation eased a few troubled minds. And bringing Dennise along also lessened the perception of anything scandalous. Charles’ granddaughters would later recall a certain resentment, perhaps even jealousy, to see their grandfather devoting so much time to this “new” woman and her children. Both Linda and Carolyn had been devoted to their grandmother and still missed her. But they also saw the happy change in him and after a decade of loss, they wanted the best for him, wherever it might lead.

Before they could set their plans in stone, Charles and Jeannette had one more issue to resolve. Dennise was 15 and excited to make the trip. But her little sister Jeanne was only four. How would she handle a 6000 mile journey over a fortnight, across some of the most rugged landscapes, and some of the hottest climates, in a tiny VW bug? They concluded—not well. In addition, young Jeanne had another complicating issue; she tended to get carsick. Jeannette asked her mother if she would consider taking care of Jeanne for the duration. Grace Beaver, of course, was delighted. To allow her to adjust, Jeanne’s stay with her grandparents began two weeks before their actual departure date. Charles and Jeannette worried that the sight of their packing for the trip, without her coming along, would be especially hard on her. As they drove away from Portsmouth, Rhode Island, Bill and Grace Beaver’s home, Jeanne’s grandparents were by her side. Little Jeanne was furious with her sister; why did Dennise get to go and not her? Grace assured her granddaughter she had no reason to fret—her mom and sister and “Daddy Charles” would be home in just a few short weeks.

On Friday morning, June 30, Charles Boothroyd and Jeannette and Dennise Sullivan piled into Charles’ green VW Bug, loaded with camping gear, and headed west for the trip of a lifetime.

*** *** ***

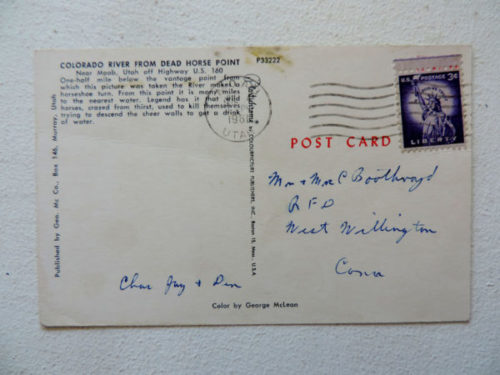

In the summer of 1961, the Interstate highway project was in its infancy and many long stretches from Pennsylvania, to Iowa, and across Nebraska were still two lane roads. The going was slow and hot in that little car. Jeannette and Charles must have taken turns driving, because their progress along that 2200 mile stretch of road was nothing short of amazing. Charles used postcards to inform his family of their forward movement. On Saturday, he dropped a card into the mail from Angora, Indiana. The next day, they were already moving rapidly across Iowa to Nebraska. Charles dropped another card in a mailbox, from Clinton, Iowa.

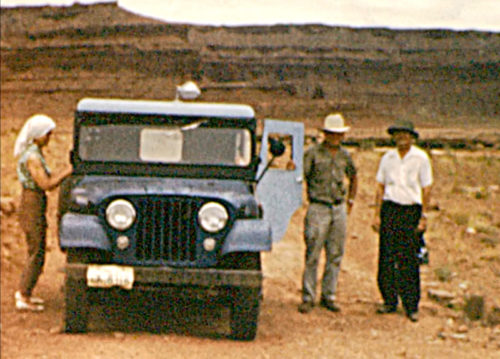

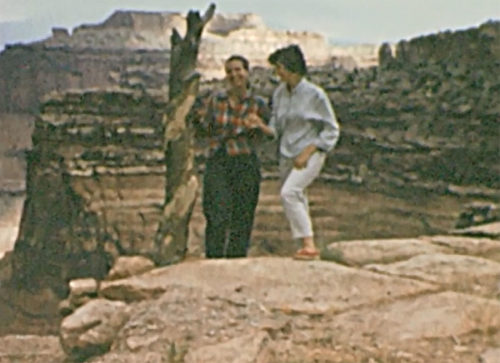

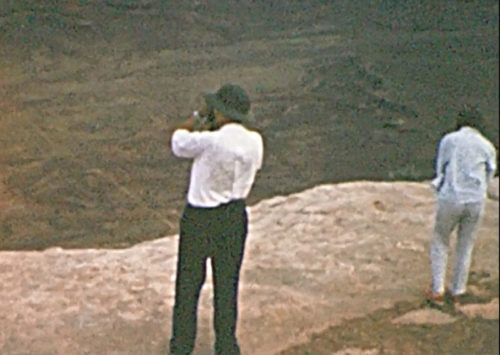

Throughout the long drive, Charles, the inveterate photographer, didn’t miss an opportunity to record their adventures; he even had an 8mm movie camera to record his two companions at various locations. When they saw a sign that read “Beaver, Iowa,” Jeannette’s family name, Charles pulled over and shot a few seconds of film. Jeannette was beaming.

By Sunday, they had reached the Rocky Mountains near Fort Collins. They turned west into Rocky Mountain National Park at Fall Rivers Pass. Slowly they wound their way through the mountains, past Iceberg Lake, and then along US 40 until they turned south on a state road until it intersected with US 6/50 seventy five miles east of Grand Junction, Colorado. They paused along the highway, just east of Palisade to watch a west bound freight train that paralleled the Colorado River. Charles filmed it all, but was particularly interested in several rail cars loaded with new Ford four wheel drive Broncos. Perhaps he was already thinking ahead to the next vehicle for his new family.

They reached Grand Junction on the afternoon of July 2. Where they stayed that night, or any evening during the trip, has never been clear. But most likely they camped out. Charles had rigged a cartop carrier for the Volkswagen which even included a small canvas pup tent. Jeannette and Dennise slept up top; Charles brought an extra cot for himself. The next morning, they arose early and Charles dropped another postcard in a mailbox. From here, just west of Fruita, the landscape opened up dramatically. To the north they could see the craggy ramparts and canyons of the Book Cliffs; on their south, the high forested ridges of the Uncompahgre Plateau.

But due west, there was nothing but high desert, rolling plains and wide open vistas. They paused at the Utah/Colorado State Line to take pictures and film. It was the day before July 4 and traffic was heavy on the old two lane. Twenty miles further west, they came to Cisco, which had only recently gained some notoriety after Charlie Steen’s uranium discovery. A few miles beyond Cisco, they turned south on a graded road. Jeannette and Dennise must have been skeptical, but Charles, ever the optimist, assured them that their little green VW could handle whatever obstacles State Highway 128 had to offer.

And he was right. They had little trouble negotiating the dirt road. Just downstream from Dewey Bridge they paused and took a few minutes to explore an old cabin that had long been abandoned. Then they followed the rough road as it descended deeper and deeper into the canyon of the Colorado River.

Finally, in the afternoon of July 3, the weary threesome rolled into Moab. They were overwhelmed. It was scenery the likes of which neither Dennise nor her mother had ever seen or even imagined. Boothroyd, while no expert, must have enjoyed his role as tour guide for the woman he planned to marry, and the young girl whom he had come to think of as a daughter. He planned to take them to Arches National Monument, but it was too late in the day. He also wondered if the monument might be busier than usual on the 4th of July. And so, before they made that side trip, Charles had another adventure in store.

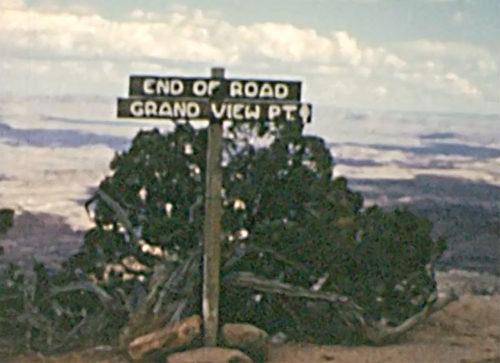

He wanted to take Jeanette and Dennise to Dead Horse Point and had hoped to travel down the nearby historic Shafer Trail on the Island in the Sky Plateau. The State of Utah had just designated Dead Horse Point as a state park in 1959, but now, two years later, access to the point was still limited to a rough, dirt road. Amenities were scarce—that summer, the state had installed a few picnic tables and grills, but there was no ranger on duty, nor was there a phone. And that’s what Boothroyd loved about the place. He was anxious to share all this remote beauty with Jeanette and Dennise. But it was getting late in the afternoon and he knew there’d never be enough time to see it all before dark, so they made plans for Tuesday, the Fourth of July.

They rose early, had a quick breakfast and stopped at the Moab post office. Charles dropped a picture postcard into the mailbox; it was another brief note, just letting the family keep track of their itinerary. On the backside of the card was a photograph of Dead Horse Point. When it arrived in Connecticut, three days later, it bore a “July 4, 1961” postmark.

With that last chore completed, they drove north on US 160. Boothroyd had come to Arches before the new road had been completed in 1958, and he may have pointed to the old entrance road as they approached their turnoff. Boothroyd turned west on the Dead Horse Point road. 25 miles later, they drove past the turnoff to Dead Horse Point, and kept traveling south on the unimproved dirt road that led them to the top of the Shafer Trail. They all got out and looked at the switchbacks and twists and turns that the old cattle trail made as it descended more than 2000 feet to the White Rim. Jeanette and Dennise probably thought Charles was crazy. And in a Volkswagen?

But Charles was feeling adventurous. They crept down the sinewing route of the Shafer Trail until they reached the White Rim. Near there, they were close enough to see the Colorado River. It looked out of place in this red rock wilderness. Tamarisk and willow grew abundantly along the river banks and the water looked deceptively close. But the cool water was far beyond their reach. Charles turned south along the White Rim trail and they got as far as the Monument Canyon Overlook before they decided the VW had been tested to the limit, and that it might be safer to turn around.

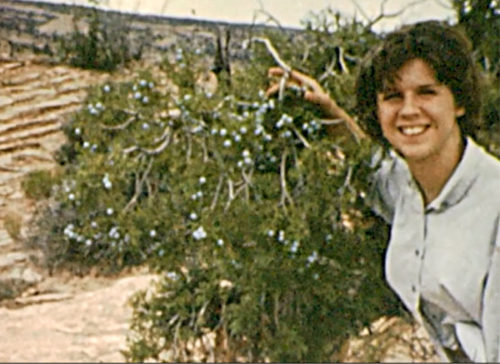

They started the long hot drive to the base of the Shafer Trail, then up the torturous switchbacks to the rim of the mesa. At the base of the worst section of road, Charles and the Sullivans stopped to talk with a couple coming down the switchbacks in a British Land Rover. Charles must have wondered if his little VW Bug was up to the task, especially in the one hundred degree heat. But he had confidence in his machine and he would have felt triumphant when they reached the mesa top. They paused briefly to photograph the trail and the land below them from near The Neck, then turned south again along the mesa top, all the way to Grandview Point. Jeannette took the movie camera from Charles and captured him and Dennise, standing together on the very edge of the 2000 foot cliffs. Below them, the river, the canyons and mesas and ridges beyond, the hazy Blue Mountains on the horizon all glowed as the sun dropped lower in the sky. The scenery stretched out before them for a hundred miles. Dennise gazed at the view, and then lowered herself to the smooth sandstone beside Charles. Soon it would be time to go.

Now it was early evening. Not only was the day winding down, some severe storm clouds were moving in. The road back to Moab was unpaved and a thunderstorm could be a problem. The Boothroyd/Sullivans climbed back into the Beetle and followed the mesa top road north, back to the Dead Horse Point turn. Though it was getting late, they still had one more place to visit. Another three miles would bring them to the parking lot and the Dead Horse Point Lookout, with its stunning vista views of the canyon country. But not far from the park, they spotted a drill rig and some oil field workers. It was known as the Brinkerhoff well site and several men were shutting down for the day. Charles realized he was short on water, so they stopped and asked the crew if they could spare a few quarts. The young men were happy to oblige and one of them took an instant interest in Dennise. As the young couple stood together, talking and laughing, Charles pulled out the movie camera and caught a few moments of film. They both looked embarrassed but happy. At one point, the young boy took Dennise’s hand and held it. She looked radiant. Charles and Jeannette both smiled. Then the film ran out. He would have to change out the reel when they got back to Moab.

They returned to the VW and drove that last mile to the Dead Horse Point lookout. Boothroyd let the engine idle a moment in the intense heat, then shut it off. The silence overwhelmed him. As Charles climbed out of the Bug, he saw the solitary figure coming toward them.

DEAD HORSE POINT.

JULY 4, 1961. 9 PM

The Boothroyd/Sullivan family had arrived just in time to prepare for a magnificent sunset. The skies were full of towering cumulus clouds and storms threatened over the La Sal Mountains to the south. They could see flashes of lightning 30 miles away. Sometimes the distant rumble of thunder made its way to the Point. The lower lying clouds were aglow as the sun began its slow descent over the Orange Cliffs and beyond.

Benny Aragon, Charles Boothroyd and Jeanette Sullivan chatted amiably for almost an hour. Aragon explained that he had grown up in the canyon country and was intimately familiar with much of the territory they could see from the Lookout. They talked about the other tourists they had seen that day. Aragon had encountered several who came and went during his long hours at the Point. As they talked, Boothroyd realized they’d met some of those same people.

Charles probably told Benny the story of their day’s drive down the Shafer Trail in his little two-wheel-drive VW. Likewise Aragon spoke of his many adventures in the canyon country and explained some of the lore behind the “Dead Horse Point” name that had been given to this magnificent viewpoint.

As far as we know, Aragon never mentioned his service in the war or his work in the coal mines. Nor did he refer to his recent financial problems and lack of work, as he had confided to Genevieve Johnson. Perhaps he didn’t want to complain in front of the girl. Maybe he no longer had the energy.

The last remnants of the day’s sun finally disappeared behind the clouds and the distant canyon rims and plateaus. Boothroyd said goodbye to their new friend, and they walked back to the beetle, started up the tired hot engine and began the 33 mile drive back to Moab. Abel Aragon nodded farewell and once again found himself alone. Darkness was coming soon.

Boothroyd had traveled no more than two or three miles when he glanced in his rear view mirror and saw a vehicle gaining quickly on them. It appeared to be the Ford sedan that belonged to the man they’d just met. The Ford whizzed by them and Charles and Jeanette wondered what the rush was. But soon Aragon’s tail lights dimmed and vanished as he raced ahead. It was almost 9 PM. Dusk.

Boothroyd didn’t see another car light for 15 minutes. But about eight miles from the junction with Highway 160, he spotted a car by the side of the road and instantly recognized it as the ’55 Ford sedan. He must be in trouble, Boothroyd thought. He remembered the times in his own past when he had broken down on some empty, godforsaken road, and always…always…the first car to come along had stopped and offered assistance. It was, in his mind, a Western tradition, and a good one. He probably pulled past the sedan, and onto the road shoulder, climbed out of the VW, and walked back a few steps to offer a helping hand. Aragon had lifted the hood of the car and appeared to be playing with the wiring. Boothroyd could see the man jiggling the spark plug cables.

“Can I help?” Boothroyd asked.

“Generator trouble, I think.” Aragon wondered if he could borrow a flashlight. Boothroyd walked back to the car, retrieved the flashlight and returned to Aragon, who slammed the hood and walked to the driver’s door. He reached into the Ford and pulled out a .22 caliber bolt action Stevens rifle and aimed its barrel at Boothroyd’s head. Boothroyd was incredulous.

“Is this a hold up?” he asked, stunned beyond his belief to express it.

Aragon almost looked as bewildered by his own actions as his victim was. Aragon nodded and said, “I guess it is… I want your money.”

Jeanette and Dennise had been watching the two men exchange words through the VW’s back window. It had all seemed so normal. Suddenly they saw the man reach through the side window of his car. They saw the flash of metal in the twilight, and they recognized the rifle. Dennise sat paralyzed in the back seat. Jeannette told her to stay put, quickly exited the Volkswagen and walked rapidly toward Charles and Aragon.

Instead of appearing terrified or intimidated by this completely unexpected turn of events, Jeannette Sullivan was furious. The exchange between Aragon and Sullivan was never told in full by Boothroyd. But he said that his fiancé was livid. Aragon demanded Boothroyd’s wallet, which contained all the cash for their two week vacation—about $250. He told Boothroyd to place the wallet on the ground. Charles immediately complied. But in the next moment, Jeanette bent over and retrieved the wallet from the sandy road shoulder. She opened it up and saw the stash of bills. She pulled from it a small amount of the cash, perhaps as little as twenty or thirty dollars. She threw the bills on the ground, kept the wallet and the remainder of the $250 firmly in her hand. She started to walk away. Aragon screamed at her to stop.

Boothroyd remembered later that Sullivan turned and said icily, “You’ve got your money now. What else do you want?” Abel Aragon replied, “I guess I will decide that.”

Jeanette Sullivan muttered something, and turned to walk away. Boothroyd heard a click…click sound. It was Aragon working the bolt action on his rifle. He loaded a fresh round into the chamber. It all happened in less than two seconds. Abel Aragon aimed his rifle at the back of her head, less than ten feet away, and fired one shot. She pitched forward into the sand and gravel. Aragon quickly worked the bolt again and turned it on Boothroyd who now stood paralyzed, just a few feet from him. Charles saw the barrel of the rifle swing toward him, heard the click-click again, and raised his hands in front of his face.

Aragon fired once more. The bullet struck Charles in the face, just below his right eye. Boothroyd collapsed on the ground but was still conscious and still desperately assuming a defensive posture with his hands, still trying to protect his head. Boothroyd remembered later that as he lay writhing on the ground, Aragon realized he wasn’t dead and, as he stood over Boothroyd, he fired yet again at almost point blank range. The second .22 slug struck him in the face, in almost the same location. The world began to spin out of control, Charles could no longer see or hear or even think. Everything was happening so fast. Boothroyd crumpled into a fetal pose, shrinking, trying to become a smaller target. Boothroyd stopped moving. He had lost consciousness.

Aragon stood numbly over the two lifeless bodies. It was Chonito Ridge all over again.

Aragon moved quickly. He dragged Jeannette out of the roadway and left her by a tree, about 25 feet away. When he shot her, she had literally been knocked out of her own shoes. Aragon inexplicably grabbed the shoes as well and laid them by Jeannette’s feet. He was about to return for Charles, who he was sure must be dead, when suddenly he saw the brake lights flash on the Volkswagen. He heard the grinding of gears.

The girl…Aragon had forgotten about the girl. Dennise had stayed in the car when Charles first stopped to assist Aragon. At first, she may have been slightly annoyed at the delay. It was almost dark, she was hungry and looked forward to a good meal and a cozy sleeping bag. Then, in a matter of seconds, her world disintegrated in front of her. She watched in terror as Aragon took aim at her mother and fired into the back of the head. She could see the blood. This was the man who just 30 minutes earlier had seemed so kind and friendly. And then there was Charles, shot twice and apparently dead as well. Suddenly this 15 year old child was completely on her own. Alone in the middle of nowhere. Dennise climbed from the back of the VW and into the driver’s seat. She had never driven a car in her life. But Charles had left the motor running when he pulled over; somehow she got it in gear and lurched forward.

Aragon by now was no longer Benny Aragon. Who or what he had become will forever elude us. He stood there in the approaching darkness, surveying his kills, lost in his rage. What next? Then he heard the Volkswagen’s engine race, its gears grind, and saw it pull onto the roadway. Benny didn’t even have time to gather his loot (the wallet and most of the cash was later recovered).

The girl is getting away.

Aragon leapt into the front seat of his sedan and punched the accelerator, spraying rock and gravel as he raced to stop the girl. Almost simultaneously, Boothroyd regained consciousness. He was still dazed, but he could see Aragon roar away and he realized that his VW was gone as well. He tried to stand but he fell back down. He was bleeding profusely from his face and hands. He could barely see out of his right eye and wondered if he were blind, or if the bullet had penetrated his brain. He looked over his shoulder and saw Jeanette in the darkness. She was motionless. Boothroyd was sure she was dead but then he heard her moan. He tried to crawl to her side but collapsed again.

At that moment, Leonard Brown, a rig foreman who was living on site at a Brinkerhoff Oil Company well near Grandview Point, was driving back to his trailer after a day in Moab. He had gone to town for the Fourth Of July festivities, to call his children and, as he told it later, “to clean up a bit” after a long week at the drill site. He had left Highway 160 at the turnoff and was traveling west on the Dead Horse Point road when he saw an eastbound car coming at him at a high rate of speed. Brown thought nothing of it and assumed it was a tourist eager to get back to Moab for the evening. But he had not traveled any farther than 200 or 300 yards when he saw the green Volkswagen by the roadside. Still, it didn’t cause alarm and he certainly didn’t sense a connection. If the driver had been in trouble, he reasoned, the car Brown had just passed would have offered assistance. That’s the way people were out here. And so he didn’t give it another thought. Nothing sinister ever happened in these rare parts.

But then, less than a mile farther west, just beyond the top of the Seven Mile Canyon switchbacks, his headlights illuminated a bizarre sight. A man lay in the middle of the road, his face and hands and shirt sleeves were drenched in blood. The man continued to hold his hands close to his face, as if he were trying to hold his head together. To Leonard Brown, it looked as if the man had been in a very rough fist fight. Brown pulled over. He jumped out of his car and ran to assist him.

“What in the hell has happened here?” Brown yelled. Boothroyd was able to speak, but just barely. Charles said he’d been shot and robbed. Brown, by coincidence, had a radio telephone in his car, which allowed him to stay in contact with his bosses in Farmington, New Mexico. Now he attempted to reach them. When he made contact, Brown explained this chaotic situation as best he could, and told them to call the Grand County Sheriff’s office in Moab immediately. It was a matter of life and death. As he waited for confirmation, Brown heard a moan coming from the scrub brush beyond the roadway. Stunned, he asked Boothroyd, “is there somebody else out here?”

All Boothroyd could say was, “I tried to move her.”

Leonard Brown found Jeanette Sullivan more than 25 feet off the highway. She was still alive but unconscious. He could see blood oozing from a wound in the back of her head.

Brown completed the call to his office in Farmington; the company had conveyed the information and help was on the way. But Brown decided there wasn’t enough time to wait for the sheriff or an ambulance. Somehow he managed to move Sullivan to the backseat of his car and then helped Boothroyd, who was growing more incoherent by the moment, into the front seat. Brown and his critically injured passengers set off for Moab. But they had scarcely traveled half a mile when Boothroyd saw his VW. It had apparently been run off the right side of the road and he told Brown to stop.

Charles said softly, “I hope the daughter is alright.” It was the first Leonard Brown had heard of a third victim. They both saw the damage to the rear bumper and to the driver’s side door. Brown jumped out and shined a light into the VW. There was nobody there.