Click Here to Read Part One…

THE SEARCH

From the moment Leonard Brown passed Aragon on the road on Tuesday evening, no one had seen a trace of the 1955 Ford or Aragon or Dennise. Despite multiple roadblocks and alerts to all law enforcement agencies within 500 miles, despite a call to the Air National Guard who put planes in the air on Wednesday morning, and despite a request to the FBI to join the investigation, the suspect and his kidnap victim had vanished. Not a single clue had turned up. In the middle of the night, Stocks called in the leaders of the Grand County Jeep posse, a volunteer organization from Moab, and explained the dire and urgent situation they faced. By sunrise, the posse, under the leadership of Cliff Aldridge and GA Larsen, had more than a hundred vehicles in the field; over the next few days they would explore every mining road and jeep trail into the barren backcountry that time would permit, in search of the missing Ford.

It’s assumed that deputies drove to the location of the Volkswagen that night and made a cursory search of the area. There was no trace of Dennise and, almost from the moment she was discovered missing, law enforcement treated it as a kidnapping. It’s unclear if the Volkswagen was towed to town that evening or left unattended by the side of the road until the next morning. But it would have been extremely difficult to locate the actual site of the shooting until daylight, when Leonard Brown returned to the crime scene with Stocks, UHP trooper Rex Nielson, and Moab City Police officer Jack Taylor. Brown was able to take them to the precise spot.

In addition to the tire tracks, a pool of blood was still clearly visible in the sand and gravel. They found one live round and three spent cartridges on the ground nearby. Aragon had not realized he had a live round in the chamber and had ejected and worked the bolt before he fired the first shot. Also lying in the sand was the money, with its rubber band still intact. Almost all of the $250 was still there. In his panic, Aragon had forgotten why he stopped them in the first place. Jeannette had picked a few bills from the wad, tossed them on the ground and started to walk away. Most likely those few bills blew away in the wind.

Finally, they could see where Aragon had dragged Jeanette into the brush, about 25 feet from the edge of the road. Aragon wore a heavy ribbed work boot and plaster casts were made of his footprint. What Aragon had planned to do next was anyone’s guess. Perhaps he thought that if he cleared the bodies from the roadway, and could somehow ditch the Volkswagen, that maybe he might be able to escape undetected. Or at least give himself a good head start. But clearly he must have forgotten about the girl.

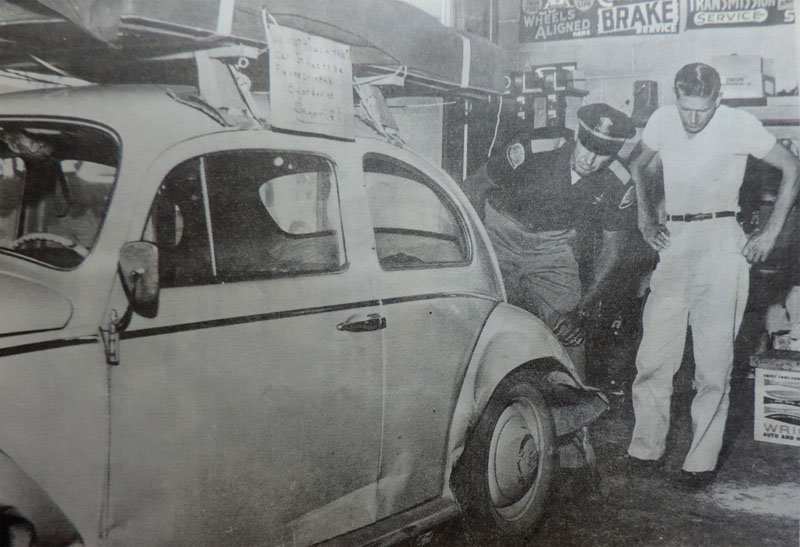

The Volkswagen was towed back to Moab, to Buck’s Garage, where the vehicle was processed by law enforcement. Stocks even placed a warning sign on the side window, advising everyone “DO NOT TOUCH,” until the car had been checked for evidence and fingerprints.

After photographing the site and collecting the evidence,the officers and Brown stood quietly at the crime scene for a few moments, still overwhelmed by the magnitude of it all. Then they returned to Moab. So far, there had been no news at all.

Meanwhile, a more extensive air search was underway. By Wednesday morning the Utah Highway Patrol had already put a light plane and a helicopter in the air. A Moab pilot, Glen Haron, who owned a Flying Service in town, contacted other private plane pilots and soon they became a part of the search too.

Coincidentally, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall was in southeast Utah that week, on a tour of the canyon country. Proposals to create a national park were a hot topic of discussion, in both Utah and Washington. Udall wanted a firsthand look and several military planes had been made available to Udall and his party. Now the wing operations officer out of Stead Air Force Base in Reno, Lieutenant Colonel Richard Fast, advised Sheriff Stocks that he would place those aircraft into the search as well.

*** *** ***

Then came an unexpected break. An employee of the Employment Security Office in Moab contacted the sheriff with the story of an odd phone call that had reached them on the previous Saturday, July 1. Word was already out that the suspect might be from Carbon County. The call had, in fact, come from a woman in Price who was worried about her husband. She knew he had come to Moab the previous week, in search of work, but she had not heard from him since. She wondered if her husband might have contacted their office. The woman left her name but it wasn’t recorded. Now the office staffer had the vague recollection that his name sounded like “Benny Oregon.” Oregon? It was too much of a coincidence. Stocks called Sheriff Passic in Price with this new information. This time, Deputy Chuck Semken was on duty and he overheard the reference. He immediately made the connection—one of his best friends, the man with whom he had joined the Marines, the guy he had known almost his entire life, was Abel Aragon. Some called him Benny. He was one of the best men he had ever known. It was impossible. But now, for the first time, law enforcement had the name of a possible suspect to match the car.

Semken was incredulous. He wondered if his friend’s disappearance could have even darker implications. Knowing Aragon as he did, and assuming he was incapable of such an evil crime, Semken pushed the possibility that Aragon might be a victim as well. Could Abel have picked up a hitchhiker along the road? He was that kind of guy, always wanting to help out somebody even further down on his luck than he was. Could Aragon have somehow been attacked and overwhelmed himself? Is it possible that this unknown person then stole Aragon’s car and proceeded to commit these other crimes? Semken was sure that they were searching for the wrong man and he feared his buddy might be dead as well.

But on Thursday morning, the Grand County Sheriff received a call from a gas station attendant in Moab. He said a woman was there, asking about her husband. The woman seemed distraught and the attendant thought she might be referring to the suspect. Law enforcement arrived within minutes and it was indeed Eva Aragon. She was frantically worried that the man involved was Benny, but hoped against hope that she was wrong. She conceded to the deputies that her husband owned two weapons—a rifle and a pistol. Both were .22 caliber. The information cemented their suspicions, and now even Semken was convinced. They knew Aragon was armed with more than just the rifle. But they still had no idea where he was. Eva Aragon returned home, with her worries confirmed.

Then on Thursday night, and for just a few minutes, law enforcement knew precisely where Abel Aragon was, down to the square foot, but before they could reach his location, he was gone again. They had missed him by minutes.

Around 9 PM, a long-distance collect call was placed from Moab to Price, Utah. The call was made from a pay phone just outside the offices of the Canyonlands Telephone Company, across the street from the courthouse on Center Street. The operator who placed the call was troubled by the man’s voice –he appeared to be in extreme distress—and she broke an inviolate company rule. She eavesdropped on the conversation. The call didn’t last long and nothing definitive is believed to have been said. But clearly the man who had just called his wife was coming apart. When the man, apparently Aragon, hung up, the operator hesitated for a few minutes. She might get fired for listening to a private conversation. But the entire community was trying to find the murderer from Price. This could be the man. Finally she called her husband, who was himself a Moab police officer. Within moments law enforcement raced to the phone booth at Center & First East Streets, but Aragon was nowhere to be found. How in the world had this man been able to drive to the center of Moab, place a call without any hint of detection, and then vanish again as quickly as he had appeared? The deputies and officers and FBI agents were at their wits’ end.

All day Friday, the search continued. Speculation that Dennise might have been thrown into the river brought out crews of boaters with grappling hooks, hoping to find her. One man, O.H. Johnson, steered his runabout up and down the river searching for clues. Near the Moab bridge, he spotted a pair of sneakers, sitting side by side on the beach. He took them to the sheriff and at first, it felt like a solid lead. But the FBI was skeptical—these sneakers were black; Dennise’s tennis shoes were red (8mm film shot that day by Boothroyd confirmed it) Further, Boothroyd himself, now slowly recovering at LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City, was shown the shoes. He could not confirm that they belonged to Dennise. It was another dead lead.

And then came Friday night, and the unlikely sighting of Aragon’s car by the FBI, coming from, of all locations, the scene of the crime. What was Abel Aragon doing on the Dead Horse Point Road, three days later, just seven miles from the killing site? Within minutes came the improbable confrontation with the FBI at Crescent Junction, and the one last gunshot that ended it all for Abel Aragon. Dennise was not in the car.

Sheriff Stocks said, “There’s only one person in the world who knows where she is…and he’s dead.” The veteran sheriff had no idea what to do next.

*** *** ***

All that was left was to find Dennise. It was assumed by now that she was dead. Stocks gave the odds of her survival at one in a thousand. The first “break” came on Saturday. Bill Beck was a miner and was in Moab on Saturday afternoon to pick up a truck he had left at a garage a couple days earlier to be serviced. Beck had been doing some prospecting on Polar Mesa, a very inaccessible plateau and a once active mining district, in the shadow of the La Sal Mountains. It was a hard 35 mile drive from the mesa to Moab. There were no telephones on Polar Mesa and Beck was just now learning the details of Tuesday night’s shootings. As he read the description of the suspect, it all sounded familiar to him and he got in contact with the sheriff.

On Wednesday morning, at 2 AM, just five hours after the shootings, a man approached Beck near his trailer on the mesa. No one has ever explained why Beck was awake at that hour of the night, or why Aragon would have seen him. But the man saw Beck and they inexplicably chatted for a few minutes. Aragon explained that he was looking for work, and said he had hoped he might check out some of the uranium mine camps. He thought he might even know some of the crews on Polar Mesa. Beck later recalled that the man didn’t seem particularly nervous or stressed, despite the fact that just five hours earlier, he had committed one of the most heinous crimes in Utah history. Nor did he notice anyone else in the car.

Then Aragon asked Beck if he might do a favor for him. Aragon handed Willie Beck a letter and asked if he would mail it for him. The stamped envelope was addressed to Eva Aragon in Price, Utah. Beck agreed to mail the letter. Aragon thanked him and disappeared into the night. The next day Beck drove to Moab to have his truck serviced. He was given a rental truck until the work was done. But he had completely forgotten about the letter, which he’d left in his glove compartment. On Saturday, when he realized that the mysterious 2 AM stranger on Polar Mesa might be Aragon, Beck called the sheriff. The sealed envelope was still stuffed in the glove compartment of his truck. Because the envelope had never been mailed, the sheriff felt legally entitled to open it. They had hoped for a clue, but it offered nothing new. In the letter was a small amount of cash and a note to his wife, telling her to use the money to pay some bills.

On Saturday morning, the day after Aragon’s suicide, law enforcement was already headed for Polar Mesa, but on an unrelated matter. Deputy Tom Wells, unaware of Bill Beck’s revelations, was checking out a wrecked car on the switchbacks below the mesa. He had surely taken the same route that Aragon followed on Tuesday night. As Aragon made his escape from the crime scene that night, he would have only stayed on the main highway for seven miles, until he crossed over the Colorado River bridge and turned left on Highway 128. The river road was dirt and gravel in those days, and few traveled it, especially at night. Aragon would have made his way along the river for 13 miles, to the junction with the Castle Valley/La Sal Loop road, where a right turn would lead him into the mountains. Eventually he would have left the loop road and followed the steep switchbacks until he topped out on the Mesa.

According to reports from that week, about twenty people were living up there in the summer of 1961. Polar Mesa had been an active mining area, specifically for uranium, going back to the early part of the 20th Century. One mining report from 1952 explained that, “The uranium-bearing Salt Wash member of the Morrison formation is exposed on the mesa sides and in part on the top.” Interest in the Polar Mesa deposits exploded in the 1950s, in the wake of Charlie Steen’s discovery. The mesa top was crisscrossed with jeep tracks and mine shafts. Abandoned trailers still dotted the flat top.

As Deputy Wells contacted some of the mesa residents regarding the wreck, he suddenly realized that the significance of his investigation was about to expand dramatically. The murder suspect that law enforcement had searched for in vain since Tuesday night, had been there. In fact, their suspect had conversed with some of the people he had just interviewed. Mrs. Nora Ince told Wells that she thought their killer had been on the mesa for a couple days. She had even shared coffee with him on a couple of mornings. News of the killing and kidnapping had reached some of the Polar Mesa residents on Thursday, though the information was sketchy. Aragon had even asked her if there had been any new leads.

Ince noticed that Aragon occupied one of the abandoned trailers, but that on both Wednesday and Thursday evenings, she had seen him leave the trailer around 8 PM. She never noticed what time he came back. And once, he came to Mrs. Ince and asked her if she had “heard a girl scream.” Ince had heard nothing, but later, in retrospect, she wondered if he was testing her. Ince and others who lived on the mesa had thought Aragon’s sudden arrival and subsequent behavior “was suspicious,” but none of them linked his actions to the July 4 crimes. No one could remember when they saw him for the last time.

He most likely left his Polar Mesa hideout early on Thursday evening, and slowly retraced his route back to the river road, to US 160, and to his inexplicable undetected phone call to Eva from downtown Moab. But then, where had he gone next? If he were seen the following evening, traveling the Dead Horse Point road to its junction with US 160, why had he somehow returned to Dead Horse mesa?

*** *** ***

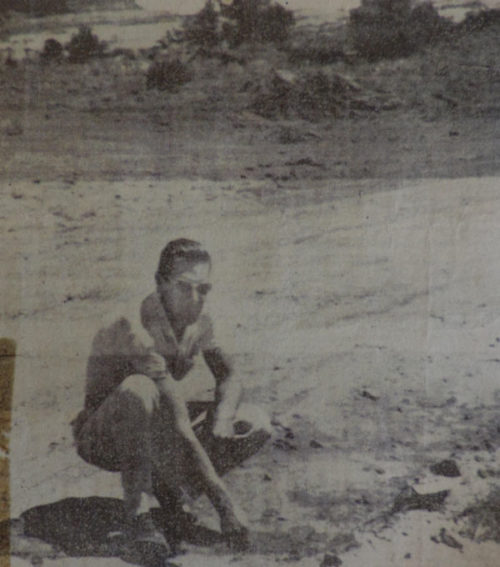

Now almost all efforts to find Dennise concentrated on Polar Mesa. If there were clues to be found, they would be here. Law enforcement officers and civilian volunteers combed the area. On Sunday afternoon, July 9, a 20 year old man, Dale White, found clothing—two pairs of men’s work pants and a red and brown work shirt—believed to be Aragon’s. They were stashed between two large rocks and partially concealed by tree foliage.

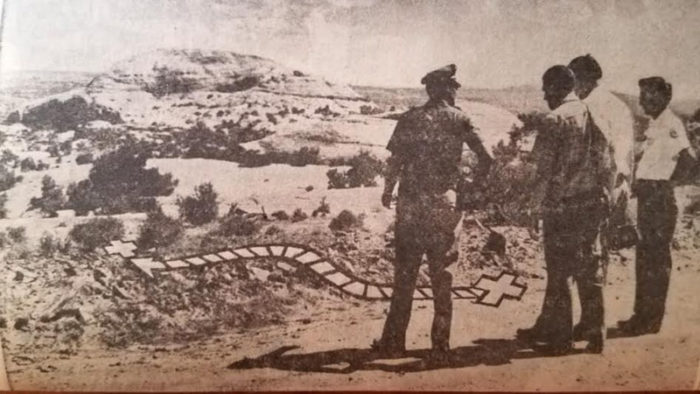

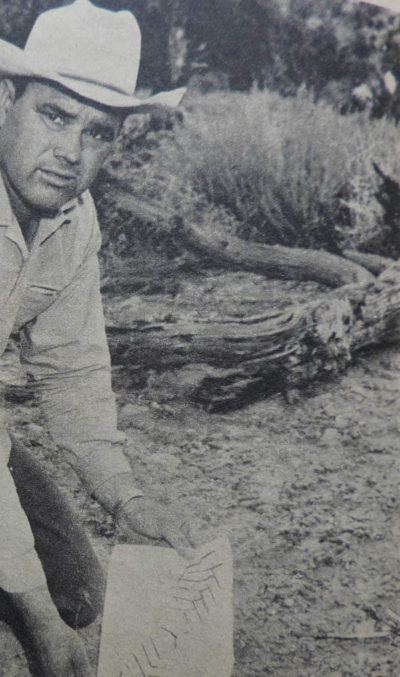

There were tire tracks and footprints everywhere. The waffle-style tread on Aragon’s work boots were easily recognized and identified, as were the tire tracks from his Ford. Sheriff Stocks said the tire tracks “went all over the place.” Ray Tibbetts, a member of the jeep posse, found shoe prints that matched the impressions at the crime scene. But the waffle prints made no sense. Whoever had been standing in those shoes had simply paced back and forth, again and again, over the same short stretch of the Polar Mesa track. He had never left the road. Tibbetts guessed he might have walked a couple miles in that short distance. He and others wondered what it might mean. Another Moab resident, Virgil Beauchamp, made casts of the prints.

That same afternoon, the searchers found something else. Tracks that were presumed to be Aragon’s were clearly discernible, but alongside them were those of a smaller individual. Conservation officer Dan Winbourne was called in to examine the footprints. A seasoned tracker, Winbourne followed the tracks for more than a mile. He noted that the smaller set of footprints stayed very close to the larger set, as if the person were being kept in check. At one point, the scuffle of tracks suggested a struggle had occurred. But eventually Winbourne lost the trail. There is no information now to indicate the specific location of those tracks or the direction they were taking. Nor was anyone able to confirm or photograph the smaller footprints. Were they definitively Dennise’s? Before plaster casts or even photographs could be taken, the desert winds had scoured them clean. Not a trace remained.

The following day, July 10, Winbourne made the most significant discovery of the investigation. Left under the thick low hanging branches of a juniper tree, Winbourne found a .22 caliber bolt action Stevens rifle, and a short handled shovel. The rifle was shown to Aragon’s 15 year old son, who denied that the rifle belonged to his father. But the rifle was sent to the FBI laboratory where tests later confirmed it was the murder weapon.

Now the search intensified. From the beginning Sheriff Stocks put his deputies on 24 hour service, hoping he could find the girl before time ran out. No one complained. And Stocks was intimately familiar with Polar Mesa; he had been a mine superintendent there in the 1930s. He pressed into service over one hundred volunteers to scour the area. Multiple shafts had been constructed on the mesa over the last 30 years. Now, miners familiar with the old mines volunteered to re-locate and search them. A miner recalled an abandoned air vent to another abandoned mine that few were aware of. A five man crew from URECO located the vent but found nothing.

On Tuesday, July 11, the sheriff heard from a man in Price. His name was Adolph Herrera and he identified himself as a friend of Aragon’s. He said that he and Benny had worked mining claims on the mesa a few years earlier and wanted to help. Herrera toured the mesa with law enforcement but he was unable to provide any additional information.

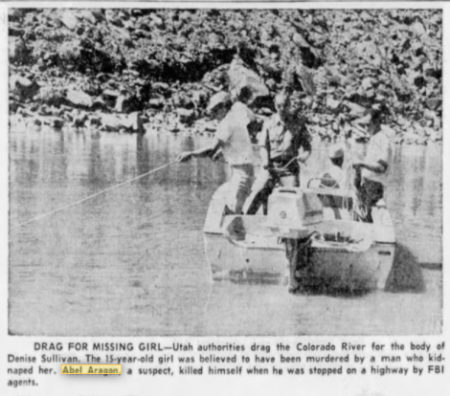

A few days later, Sheriff Stocks himself thought he might have found a clue, in a very different location. Fourteen miles upstream from the Colorado River Bridge, he had found footprints in the mud, along the river bank. It appeared as if someone had dragged an object to the water’s edge. He called for assistance and consequently, the river was dragged for days, at various locations, by Moab boat club skipper M.J. Henningson and search leader Eben Scharf. Skin diver Jack Taylor offered his services and searched various locations. In places on the river where the current was too swift and particularly blocked by rapids, a man named F.M. Pimpell offered his services as a professional kayaker. He scoured the river above and below the rapids for her body.

Again, their efforts yielded nothing.

THE AFTERMATH: ONE WEEK LATER… A YEAR LATER & BEYOND

In the days since the murder/kidnapping, the story had spread across the nation. It was front page news on daily newspapers, coast-to-coast, and was reported in national television newscasts. Every wire service sent reporters to Moab. Life magazine carried a story in its next issue and sent a photographer as well. Eventually, Robert D. Mullins, who reported the story for the Deseret News, won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the July 4 murders

The publicity led to hundreds of calls and scores of “tips,” from as far away as Chicago, Connecticut and North Carolina. One caller suggested the murders were linked to similar homicides in Nevada that had occurred the previous year. A man visited the sheriff’s office in Moab and asked for a piece of Dennise’s clothing or a blood sample. Later a deputy explained that the man was convinced he could find the girl “via some adaptation of the ancient ‘witchcraft stick.'”

In San Juan County, the sheriff received reports of “suspicious” travelers with a teenaged girl. They had been seen near the Four Corners Monument. Law enforcement raced to the area, but the suspects were merely a family of tourists who had just left Natural Bridges National Monument. In Moab, a man was seen filling his gas tank at a service station on Main Street. In the passenger seat, a girl sat quietly. The attendee thought the girl seemed troubled and called the police. The girl was the man’s daughter.

Some even speculated that the murders might have something to do with the “Death Alley” murders. Recent news reports had noted a string of murders that had occurred along US Route 66. Since 1954, 26 tourists had been reported murdered or missing along the highway, from New Mexico to California. Of the total, only 19 had been solved. People were desperate for explanations. Clearly this wasn’t one of them. Route 66 was also 250 miles south of Moab.

One report was more specific. A couple, only identified in news reports as “the Petersons,” were camped at “Day’s Cabin,” on the night of July 4. The cabin was located near the Castle Creek crossing of the road to Polar Mesa. Late on that Tuesday evening, they both claim to have heard a gunshot and a car door slam. They reported their experience to the sheriff’s office, but again, the tip led nowhere.

As the second week of the search drew to a close, hopes of finding the girl were fading. A frustrated Sheriff Stocks told reporters, ” All we can do is check and re-check that seventy mile strip of land between the murder and Polar Mesa…I hope we can find the girl, if only to give her a decent burial.” By the third week of July, all hope of finding Dennise Sullivan had faded to nothing, though over the next few months, searchers continued to scour the area for clues. Tourists who visited Moab had heard the story, and throughout the summer, the most commonly asked question was, “Did they ever find the girl?”

*** *** ***

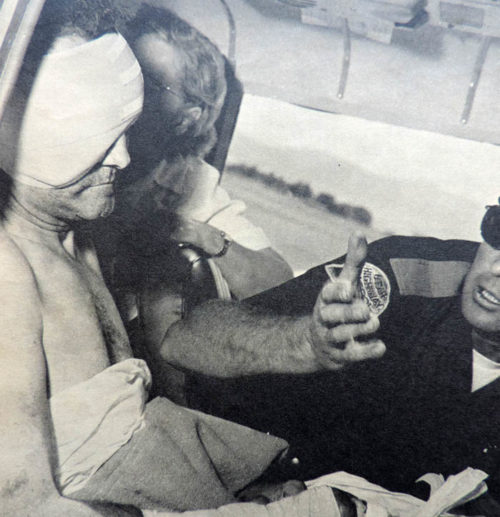

On Saturday, July 8, Charlie Boothroyd and his Uncle Ernest finally reached Charles at LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City. He had already undergone surgery for the damage to his hand. More operations would follow. The slug had struck him in the face, below his right eye and days later, his vision in that eye was still blurred. The doctors thought it might never improve. His head and right eye were wrapped in bandages and his right hand was in a cast. But he was alive. He had been able to look at photographs of Abel Aragon and he made a positive identification.

Because son Charlie and Uncle Ernest both worked, they reluctantly left Charles and made the long drive back home. By July 10, they had already crossed back over the Rocky Mountains and were headed east, back to Connecticut.

On the same day that Charlie and Ernest reached Salt Lake City, the body of Jeanette Sullivan was transported to Salt Lake City by hearse. Three days later, her casket was placed on a train to Boston, Massachusetts, where it was met by her parents on July 11. The funeral was at the Ashton Funeral Home, on July 13 in Fall River, Massachusetts, followed by a service at the St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church. Three clergymen, from Fall River, Portsmouth, and Rockville officiated at the service. Then the cortege slowly made its way to the St. Paul’s Cemetery in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, just 15 miles south. Jeannette Sullivan was laid to rest later that afternoon, not far from her childhood home. The family had considered delaying the funeral, in hopes that Dennise’s body might be found and they could be buried together, but they were advised that it was now unlikely the girl would be found.

Two days after the shooting, Jeanne’s Aunt Dot, Grace’s sister, finally told the little girl the truth, or at least part of it. It was hard for the child to absorb it all, but Dot told Jeanne that neither her mother nor her sister were ever coming home. She told Jeanne that they had died “in an accident.” Jeanne never returned to the home she had lived in for the entirety of her short life with Jeannette and Dennise. It simply didn’t exist for her anymore. Suddenly she saw many of the items that had been a part of her home in Rockville now relocated to her grandparents’ house in Portsmouth. The life this small child had known and had taken such comfort in was suddenly gone. It was impossible to explain.

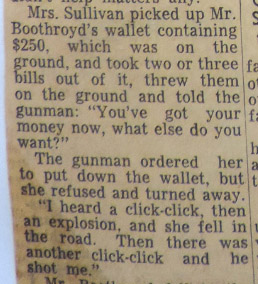

Charles Boothroyd spent three more weeks in LDS Hospital and endured several surgeries to repair the damage to his hand and face. He was allowed to be interviewed by reporters, a week after the shooting, and was able to recount the incident in amazing detail. He talked about Aragon and described “what a friendly guy” he had first appeared to be. But he became “a different man” when he pulled out the rifle and Boothroyd regretted that Jeannette had been so confrontational. After Aragon demanded their money, Sullivan climbed out of the Volkswagen and according to Boothroyd, “she started to argue with him, which didn’t help matters any.”

According to the Deseret News story, he remembered that “she picked up the wallet containing $250, which was on the ground, and took two or three bills out of it, threw them on the ground” and started to walk away. Aragon demanded that she stop and Boothroyd recalled that she said, “You’ve got your money now, what else do you want?” In the next second he opened fire. Boothroyd would also be haunted by the “what ifs,” the split second moments that changed the course of his own life, and proved fatal to Jeannette and Dennise. “If she hadn’t turned her back on him,” he pondered, “maybe he wouldn’t have shot her….that action did bother the man.”

Boothroyd had nothing but praise for his doctors and nurses and for all the assistance law enforcement officers had provided him since the ordeal began on July 4. “Everyone I’ve met here—but one man—has been swell,” Boothroyd insisted. He couldn’t really condemn Aragon. “I don’t know how I feel about him…but I do feel sorry for his five children. I hear that he was a good father and it is going to be tough on them.”

He could barely contemplate Dennise’s ultimate fate. The thought of the girl who he had started to love like a daughter was more than he could bear. There was no longer any possibility of a happy outcome. “I wish they could have found Dennise, but it’s one of the nightmares I take home with me.” Pondering her fate, he found himself hoping that she had met a quick and “merciful death.” He told reporters, “I only hope that he remained in the same frame of mind that he was in when he killed Jeannette and shot me. Maybe then he killed Dennise right away.”

The alternative was unbearable. “It would be terrible if he had left her alone on the desert to die.” Boothroyd was overwhelmed by the thought of it.

On July 25, Boothroyd’s son Charlie booked a United Airlines flight from Hartford, Connecticut to Salt Lake City. His father, now without his facial bandages, still tired easily and his son hoped he could make the trip home as comfortable for him as possible. Incredibly, the plan was to make the long drive to Connecticut in the same damaged Volkswagen that had carried Charles, Jeannette and Dennise to their deadly encounter on Dead Horse Mesa. It would be a long and circuitous route.

After thanking the staff at LDS hospital for their extraordinary care, father and son left Salt Lake City by Trailways bus to Price, Utah. Charles’ Volkswagen had been towed to a shop there to make repairs to the battered vehicle. Charlie sent a postcard to the family. He reminded them that, “…when dad and I get home, don’t rush him as he is still pretty sore.”

Then the Boothroyd men traveled another hundred miles south, back to Moab, to retrieve the personal items that he and Jeannette had left at the campground on the morning of the Fourth. He had finally come full circle.

The next morning, they drove the VW back to Salt Lake City and then turned east. Charlie might have been worried about attempting to push the VW over the high mountain passes in Colorado. As they made the slow journey, via Wyoming and Nebraska, Charlie sent more postcards to his wife Gracie. On July 30 he and his dad had reached Boone, Iowa.

“I sure wish we were together,” Charlie wrote. “I expect to be home Tuesday AM, so don’t tell anybody. I love you and I’ll see you soon” He was clearly hoping that he and Charles could avoid the media frenzy already descending on the Boothroyd’s home in Tolland, Connecticut.

Slowly the Boothroyd father and son made their way across America, often re-tracing the same route that Charles and the Sullivans had followed, just three weeks earlier. It must have felt like a different world and a different lifetime. On August 3, they reached home. Charles was still in a great deal of pain and his vision had not cleared. Charlie brought his father to his house in Tolland; his daughter-in-law Grace and two granddaughters, Linda and Carolyn, were there to meet them. The Boothroyds were a close-knit family and, for the two girls, their father’s departure on July 25 at the airport had been one more painful consequence of the shootings. Now, finally, both father and grandfather were back, though it was clear that Charles was still badly incapacitated. He lived with his son and family for several months as he recuperated.

As the granddaughters watched the small green VW come into the driveway, they both noticed the damage to the rear fender and the long scrapes along the driver’s side of the car, but their grandfather said nothing, and their parents wanted the girls to avoid the subject as well. They wanted to let Charles have some time to settle in.

But he was not ready to rest yet. The very next morning, his sister, Mabel Anderson, drove Charles to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, to the home of Jeannette’s parents. It was an unbearably painful meeting for William and Grace Beaver and for Charles. He had been able to bring some of Jeannette’s and Dennise’s possessions back with him. He even managed to return the straw hat that Dennise wore for much of that bright and sunny day. But otherwise, there was little that could be said that might offer even a degree of comfort. The only consolation was the intensity of their shared grief.

Finally, he wanted to see Jeanne. He knew it was impossible to explain the horrors that had taken both mother and sister from this small child. There were no words. But more than anything else, Charles wanted Jeanne to understand that he was still very much alive, that he loved her like his own daughter, and that he would always be there for her. It was a promise that Charles Boothroyd made to Jeanne, and one that he kept.

*** *** ***

On Wednesday, July 12, a Requiem Mass was held for Abel “Benny” Aragon at the Notre Dame de Lourdes Catholic Church in Price, Utah. He was buried in the Price City Cemetery. That week, Alex Bene Jr, the editor of the local paper, the Sun Advocate, wrote a poignant editorial about the week’s stunning revelations that had shaken the community to its core. In part he wrote:

Another tragedy which screamed headlines throughout the land has struck southeastern Utah not only for the Sullivan family of Connecticut but for a Carbon county family. We do not condone the actions of Abel Aragon in this instance but what are we going to allow to happen to the innocent family left by Abel Aragon. How are we going to explain to our children so that they will not make heartbreaking remarks to the children of this family?

We can only ask ourselves the question: “Why do such things happen to an apparently normal person?” When a man, who has served his country valiantly in time of war, has saved other people’s lives, has loved his wife and children and tried hard to provide for them, to give them a good home, and to rear them to be religious law-abiding citizens, commits murder, can such a person be in his right mind?

The Aragon family needs the tolerance and understanding of everyone in the community. Can’t we all try to ease their pain in giving them the compassion and understanding they so desperately need?

Earlier, he had told the Deseret News that Aragon “had become despondent, couldn’t find work in the mines…it was the only thing he knew.”

*** *** ***

In July 1962, the Salt Lake Tribune and reporter Dan Robinson looked back at the events of a year earlier. Robinson contacted some of the men who were deeply connected to what had even then become an enduring mystery. What happened to the girl?

Sheriff John Stocks still agonized. He feared Dennise had most likely been thrown into the river and felt sure she would never be found. But he was clearly still haunted. “I don’t know what we could have done differently. Cooperation from everyone was wonderful. It’s a sad thing…”

Bates Wilson, the superintendent at Arches National Monument had also been an active participant. In fact, early rumors suggested that Aragon may have tried to escape into the Arches. Bates remembered that it was “a terrible time…I have a daughter about the same age as Dennise, and I couldn’t help shake the thought that the girl might be tied up somewhere in the heat, without water or food. That’s why we checked every shack and abandoned mine we could find.”

Leonard Brown, the man who had passed Aragon’s car on the road and had found Boothroyd and Sullivan after the shooting, told the Tribune that, “I still can’t shake what happened and I still cannot believe the girl was in that car when I passed the car, just minutes after the shooting.”

For years, tourists to Moab would ask about Dennise…did they ever find the girl? And locals would hike into the highlands near Polar Mesa, when given a chance, to search for any sign that might have been missed.

Gemie Martin would still remember, decades later. It was her mother, Genevieve Johnson, who had offered Aragon a place to camp in their peach orchard, just days before the incident. Martin wrote recently:

“My parents did not talk much about this incident within my earshot, but I was aware of it. I began having nightmares and was noticeably more anxious than normal during the day. Mama began to question me in order to determine what my problems were. I confided to her that I was worried about being kidnapped. I remember her assuring me. ‘You don’t have to worry about being kidnapped; your parents are poor.’

“‘Hallelujah, we’re poor,’ I remember thinking. I immediately felt more secure, wrapped in the protection of our poverty. Mama did not tie the reason for my fear to the kidnapping of Dennise Sullivan, who was likely taken because she was a witness to the murder and attempted murder. It wasn’t until I was several years older that I realized I could be kidnapped for reasons other than ransom.”

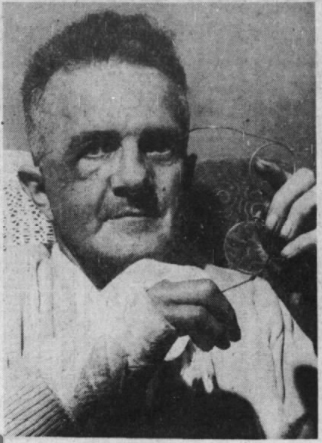

Two thousand miles away, in Rockville, Connecticut, Charles Boothroyd healed slowly over the next year. He had finally returned to his job as a machinist for Merrow, the same company he’d been employed by for 29 years. His life in most respects had returned to normal. He traded in the battered Volkswagen, but had replaced it with another one. The nightmares were not as frequent and he had finally been able to sleep without medication. He could no longer ponder the ‘what ifs.’

Now all that was gone and he was trying to move on with his life, but it never went away completely. He could never escape the thought of Dennise, the happy girl with the bright future. He told a reporter, “I get the feeling I should go out there and look for her, or try to find her grave.” He thought for a moment. “But people don’t realize how big the country is out there.” It was the nightmare from which he could never fully escape.

EPILOGUE

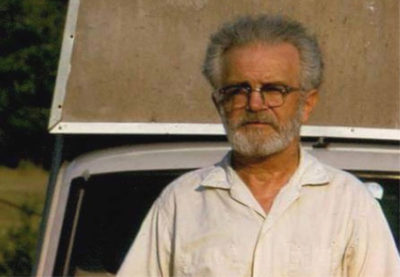

In the summer of 1964, Charles Boothroyd returned to the West, to Utah and to Dead Horse Point. He was part of a four car “Volkswagen Caravan” this time. The granddaughters called him their “wagonmaster,” and he occupied the lead car. He shared the ride with his nephew Wayne Boothroyd. Charlie and Grace, with Linda and Carolyn, rode in VW #2. Friends of Charles, Bob and Barbara Newth drove the third Beetle and another nephew Bryant Boothroyd and his wife Jackie completed the quartet.

They followed a similar route to the 1961 drive, but construction had continued at a furious pace on the Interstate highway system across America, and many more miles of I-80 had been completed in the last three years. Each of the Beetles was equipped with a rooftop carrier, exactly as Charles had rigged his travel cars in the past. Less than a week into the journey, they reached Moab and the four vehicles made their way up Seven Mile Canyon to Dead Horse Point. They passed the location where Dennise had been pushed off the road and they passed the shooting site. Charles never stopped or even acknowledged the moment. He never said a word. It was the way Charles dealt with the tragedies in his life, a trait that he clearly passed on to his son. Young Charlie never pressed his father for the details and Charles never offered them. Not once for the rest of his life could Linda or Carolyn ever remember a moment when Charles mentioned that terrible day.

In the years to follow, Charles resigned himself to a life alone. He must have wondered if this wasn’t the life he was always destined for. He had always been a loner. His wife Dorothy’s debilitating illness kept her from being the traveling companion that perhaps he had hoped for. After her death, and the arrival of the Sullivans in his life, Boothroyd had thought he was about to start life all over again. But that new life had ended almost as quickly as it began.

Now, after the 1964 trip with the family, his urge to wander was rekindled. Though the family worried for his safety, Charles was determined to return to the road. His trips out West became more frequent, especially after he retired from Merrow in 1972. Sometimes he traveled with his grandson Arthur, but often he went solo. He bought a dune buggy and drove it all the way to Alaska. Later he replaced the buggy with a VW campervan, and then a Toyota Chinook. On every trip, he brought home special rocks for the granddaughters from some exotic location; he would inscribe the the rocks’ original location on the bottom, so the girls would know precisely where they came from.

By the late 70s his health had declined, but he refused to stop traveling. The family insisted that he call them every few days, just to check in and let them know his whereabouts. Charles usually complied, but on one trip, the calls stopped coming. Weeks passed, and fears for his safety led Carolyn to contact the Stafford, Connecticut state police. They could offer little advice and all the family could do was wait.

Finally, a week later, the phone rang. It was their grandpa. He told them he was “recuperating” in a motel in Florida, but he could barely recall how he got there. Weeks earlier, he had been in Mexico, somewhere on the Yucatan Peninsula and had hit a deer. For reasons that made no sense at all, the Mexican authorities arrested him and for several weeks, held him in jail, without bail, and without the opportunity to even make a phone call. Finally, he was released as inexplicably as he was arrested. Charles made his way back to Texas and along the Gulf Coast. And then, finally, he called home. He explained that he didn’t want to worry them by drawing them into yet another crisis on the road.

Later, Charles went back to Mexico. When he returned to Connecticut, he casually mentioned to his granddaughters that he’d picked up a couple hitchhikers who proceeded to threaten him with a machete. But he explained, “all they wanted was my chocolate.”

He had a strange habit of pushing his vehicle as many miles as he could on a tank of gas. He’d be riding on fumes but he kept gambling his way toward the next service station. Sometimes he didn’t make it. He eventually bought a small motorbike that he lashed to the back of the Chinook—that way, if he did run out of gas, he’d have alternative transportation to fill the emergency can he kept with him.

His wanderings in those years sometimes bordered on the reckless. He usually traveled alone so he rarely placed anyone else in jeopardy. But it was almost as if the only way he could bear to keep going forward was by living dangerously close to the edge. Whether, at last, this was the kind of life he had always longed for, or if quietly and alone, it was the only way to deal with the long list of tragedies that he had endured, no one knows. He never talked about any of it—he never mentioned Albert and Korea, or Dorothy’s long illness and early death. He never shared his feelings about Jeannette and Dennise. He was inscrutable.

But if anyone thought he showed a callous disregard for the past, they were wrong. Throughout the years, no matter how far he wandered, or how many miles he traveled, Charles never forgot his promise to Jeanne.

*** *** ***

For the little girl who had suddenly found herself without a mother or a sister, life was a bewilderment. How does a five year old begin to understand that a mother and a sister can simply be gone? Her grandparents did all they could do to make the transition as painless as possible. Jeannette’s apartment was cleared out and all of her personal belongings moved to Portsmouth. Jeanne would see something—a personal item that had been her mother’s or Dennise’s—and it would trigger a memory. Was it better to hide all these connections to the past, or was it important that she remember her family? These were questions that Grace and Will Beaver must have agonized over.

It had been her Aunt Dot who told Jeanne that her mother and sister were dead, a couple days after the murders. It was a task that Grace could not bear. Jeanne later recalled, “I wasn’t sure what to feel…it just felt so strange. It was hard for me to understand at first that I was never going home.” Yet somehow, though she had never experienced it, she understood what death meant. Years later, she would wonder how a four year old could have grasped the magnitude of it. But somehow she did.

For weeks and months, she would cry herself to sleep at night. In the next room, her grandmother endured the same recurring nightmare—she would dream that she had locked Jeannette out of the house and would race down the steps to unlock the door, only to find no one there. She would dream it again and again. Jeanne would hear her grandmother in the middle of the night, talking in her sleep, crying out, “Oh God. Oh God,” reliving the nightmare trapped inside another.

Because Jeanne’s biological father was still alive, and technically her legal parent, her grandparents went to court to gain custody. Dennis had played no role in Jeanne’s life; she barely remembered him. He had moved to California in 1958 after the divorce and, except for one brief visit at Christmas, had not been in touch with his children at all. In October a hearing was scheduled in a Portsmouth, RI court to decide where Jeanne would spend the rest of her childhood.

As her grandfather William prepared to see the judge, he suddenly felt weak and collapsed on the bed. Jeanne found him unresponsive and ran for her grandmother. Grace called for an ambulance, but by the time they arrived, he was gone. His heart had stopped. William Beaver died on October 17, 1961. He was 78 and the stress of the last few months had overwhelmed him. He died in front of his granddaughter, barely 100 days after the nightmare of July 4.

A little more than a month later, on November 30, after several hearings and “after long thought,” Judge Michael De Ciantis awarded full custody of Jeanne Sullivan to her maternal grandmother, and now widow, Grace Beaver.

Three petitions for custody had been filed with the court. Jeanne’s aunt and uncle, Florence and William H. Morse had filed, as had Jeanne’s biological father, Dennis Sullivan.

The judge dismissed Sullivan’s claim out of hand. The Newport newspaper article subsequent to the judge’s decision reported that:

“…although the natural father is ordinarily the one to get the child, evidence shows that Dennis Sullivan has never contributed to the child’s support, has never visited his children, and has shown little interest in them until now. The judge pointed out that Jeanne does not know her father.

“Evidence proves that Sullivan, who has been married four times, has never elected to assume parental obligations, and is unfit to have custody of Jeanne.”

With regard to the other petition by Morse, who was also a police inspector, the judge expressed additional concerns:

“…although Inspector Morse has a fine home and an unquestionable reputation, the unhealthy condition of the family animosity that exists among the Sullivans and in-laws would ‘brush-off’ on Jeanne, were she to become a ward of the Morses. He said that she would become the object of family contention and hostility, and that to live in this environment would mar her future.”

The judge also expressed concern over Inspector Morse’s “reputation as a strict disciplinarian. If strict discipline were exercised over this child, her future would be harmed.”

Finally Judge De Ciantis noted that Grace Beaver had intimately known her granddaughter since birth and that everyone agreed Grace was an unquestionably fine woman and a fit person to take care of Jeanne.”

His only concern was her age and he noted that despite that, Grace Beaver was an “active, agile and healthy person who had all the qualifications to make Jeanne a happy child.” Jeanne would stay with her grandmother.

Eventually, the court allowed Grace to legally adopt Jeanne—she became Jeanne Doris Beaver. As Jeanne later recalled, “Now we only had each other.”

(Jeanne never heard from her father again. Later it was reported that he moved to Florida and died in 1985.)

Grace Beaver now devoted her life to her granddaughter. Jeanne would grow up in the same house as her mother. The Beavers had built the Portsmouth home in 1933 after William retired from the military. Jeanne was surrounded by memories of her mother, but she took great comfort in the love and compassion of Grace. When she was ten years old, Grace told Jeanne the truth about the circumstances of her mother’s and sister’s death. For the first time, Jeanne realized that beneath her sister’s gravestone, she wasn’t really there. For years, they both hoped against all reason that perhaps Dennise was still alive. That perhaps she had suffered a brain injury that caused amnesia. They fantasized that perhaps some strangers had found Dennise, had taken her in, helped her heal, and raised her in a happy home. They knew they were lying to themselves but it was something to hold on to.

Even into the 1970s, when Grace was well past 70 and could no longer take care of their Portsmouth home as she wanted to, she was afraid to sell the place. Jeanne remembered that she resisted “giving it up… She was hoping that someday my sister could come home and if she did, it would’ve been the only home that my sister would know.” Otherwise, Grace wondered how Dennise would ever find them. But she recalled, “…as the years went by, my grandmother knew she wasn’t coming home.”

Despite the terrible loss that had been inflicted on their family, Grace Beaver never resorted to bitterness or blame. It was a lesson that Jeanne never forgot. When she was old enough to learn the truth, Jeanne and her grandmother discussed the events of that day and, later, Charles offered his own recollections. Though he never spoke of it otherwise, he must have felt he owed it to Grace and Jeanne. Over the years, Grace sometimes spoke of “that poor, poor woman.” At first Jeanne thought she was remembering her mother and sister, but that’s not who she meant. Grace was thinking of Eva Aragon, the murderer’s widow. Grace tried to impress upon Jeanne “that there are two sides to every tragedy, that we need to show compassion even in our own suffering.” That lesson meant everything to Jeanne and made it easier to live with the loss. As Jeanne recalled later, “because of that, we never hated Abel Aragon for what he did.”

As the years passed, Jeanne’s connection to her past and to the life she had lost was kept alive by the promise Charles Boothroyd made. She had known him as “Daddy Charles” when she was four and he would continue to be “the father she never had” for the next 20 years. He was always there for birthdays and Christmas when she was growing up. He often came to Portsmouth and stayed at Grace’s home in the guestroom. He even brought his home movies with him to show Jeanne. She had married in 1974 and later divorced. In 1979 Grace passed away at the age of 85. Jeanne could only hope that her mother and sister and grandparents were together again. She might have felt totally alone, but she knew she wasn’t. In 1981, Jeanne remarried and Charles Boothroyd was there as “father of the bride.” It was his great honor to give the bride away.

(Jeanne Nabozny and her husband Lawrence celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary this year.)

*** *** ***

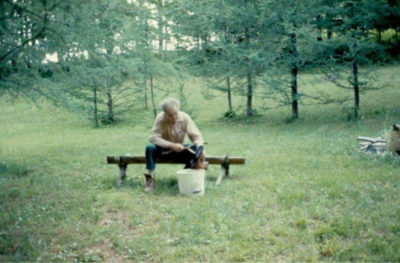

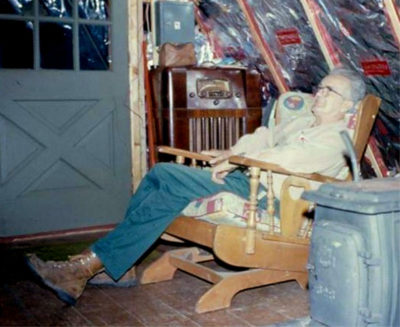

Before young Albert Boothroyd left for Korea, he told his family that he dreamed of coming home, buying some land in rural Vermont and making a life there for himself. Twenty years after his death, his brother fulfilled Albert’s dream. In July 1971, Charlie found some forested land near Chelsea and immediately went to work on an A-frame cabin. It became the Boothroyd family’s own “fortress of solitude.” To this day, it remains in the Boothroyd family. Throughout the seventies, Charles took comfort there as well. He was slowing down, not traveling as much or as far. But he still kept his memories and his feelings to himself. There’s a photograph of Charles, sitting in a recliner chair at the A-frame, listening to an old cabinet radio. One can’t help but wonder what he was thinking.

In 1983, Charles suffered a serious stroke. He could no longer drive a car and could no longer live independently. He sold his beloved Toyota Chinook camper—his great escape vehicle—to granddaughter Carolyn. Charles never had the chance to see Jeanne again. For a few years he lived with his daughter Lillian Lord, her husband Robert, and their children in Marlborough, Connecticut. Finally his health declined so severely that the family had no choice but to place Charles in the Rockville Memorial Nursing Home. He died on November 30, 1989 and was buried at the Grove Hill Cemetery in Rockville beside Dorothy. He had lived another 28 years after the Dead Horse Mesa shootings. Those years were a gift to him, for reasons he could never comprehend.

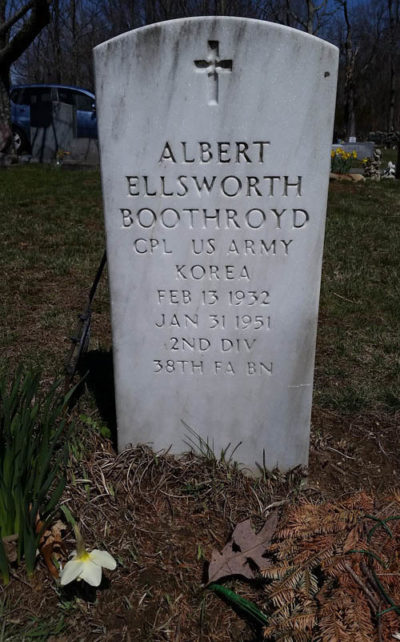

In a shady section of the Marlborough Connecticut Cemetery, just off East Hampton Road, is a simple stone marker. Just 19 miles south of Rockville, the grave site remembers the life of young Corporal Albert Boothroyd. The family still visits his memorial from time to time, though they know he’s not really there. He died as a prisoner of war January 1951, along the North Korean frontier at a place called Pukchin-Tarigol — the notorious Hofong Camp. On the hillsides and in unmarked mass graves lie the remains of several hundred young America soldiers, including Albert. Efforts by the family over the last 70 years to return him to the United States have been unsuccessful.

Eighty miles east of Albert’s gravestone in Marlborough, the St. Paul’s Cemetery in Portsmouth, Rhode Island bears another stone. It recalls the memory of Dennise Sullivan. The marker resides adjacent to her mother and her grandparents. Like Albert, Dennise isn’t really there either. On the 60th anniversary of the shootings, Dennise’s little sister, Jeanne, now 65 years old, still remembers, and still grieves and still forgives…

“All we can do is have compassion for people with mental illness. All we can do is understand that other people are suffering too, and be content with even the little bit of joy that we have in the very small things, whether it’s a hot cup of tea from my grandmother’s China or a song that we remember in our heart or a memory that means everything to us.

“I would’ve rather had my life with my family, having a mother to go to, having a sister to share my life with… we should’ve been able to have all that. But it was gone forever and there’s no mending it. And so now we still wait…I just wish I could bring her body home, even if just little bits are left. But if I never get to do that, I have to believe that someday we’ll meet again, somehow, because without that, my heart would really be broken.”

*** *** ***

All these decades later, that once lonely stretch of dirt road to Dead Horse Point has changed. It has a route number now. A few years after the shooting, the Utah Highway Department designated the road State Route 313. In the 1970s, the road was paved to Dead Horse Point and in the late 1980s, it was realigned and “improved,” and the pavement was extended all the way to Grandview Point in what had become, in 1964, Canyonlands National Park. Now hundreds of thousands of tourists and recreationists race along the same road as they hurry to the next “scenic viewpoint,” to briefly enjoy the view and shoot a quick selfie for their social media followers before sprinting to the next photo opportunity. Motorists in SUVs and motorhomes pass the precise location where Aragon opened fire on Jeannette and Charles. The site is now directly opposite a mountain bike trail staging area. There’s no memorial there. No marker.

Less than a mile farther east, near the top of Seven Mile Canyon, Dennise’s desperate attempt to escape came to a brutal end. There’s no marker there either. In this magnificent canyon country, beneath a brilliant desert sun, where the interplay of light and shadow constantly transforms the landscape, there is not even a hint that such a such a horror could have occurred, or that the sadness and grief it created still lingers. But for those who do remember, for those who still care, the shadows never go away.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the February/March issue of The Zephyr, I want to add a postscript to this story. As we’ve noted, the 60 year old mystery of Dennise Sullivan’s disappearance continues to haunt her friends and family. And now me. The Zephyr’s efforts to obtain reports and information regarding the evidence collected at the time have, so far, been futile. We are still waiting to hear from the U.S. National Archives with the understanding that some of the FBI information was transferred to them.

But I believe there is still some merit in reviewing the wealth of information that was available via the press reports of the time, as well as witness statements made later. We need to critically examine the various theories that have been suggested over the years, and perhaps add some new insights. In February, look for another article:

“Sixty Years Later… Still Searching for Dennise Sullivan”

Also…one request for help. The key witness in the Sullivan/Boothroyd shootings, besides Charles himself, was a man named Leonard Brown. He was a rig foreman for the Brinkerhoff Oil Company and was living onsite. It was Brown, as you’ve just read, who found Boothroyd, moments after the attacks.

Leonard Brown would have probably been in his early 30s at the time and I believe he may have had Moab family connections. If any of our readers have information about Mr. Brown, remember him, or might be a family member of his, PLEASE contact me. My email address is: cczephyr@gmail.com

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Well done Stiles. Very well done.

Jim, I read both parts one and two. Thanks for all the hard work and gripping writing that you put into these articles.

This is an amazing piece of writing. Now I’m haunted too. I’m hoping that the remains of Dennise will be found while Jeanne is still alive so that she can know that her sister is at rest.

I’m glad to finally read Part 2 of this story. The detailed reporting made for a very interesting read. Of course, I was hoping for a more satisfying end to the mystery of Dennise’s disappearance. Thanks for undertaking a long form journalistic project like this. Can’t wait for the next piece.

A tragic story told with amazing writing. Thanks for taking the time! May Dennise be found…

I’ve driven by that location a few times in the past year and just finished your excellent articles. Gives me goosebumps when I look back at my photos. Hope she is found and laid to rest with her family

Am learning about this in my history class at school and I just pray they will find her I also think that the lights in the beginning of the article that the police shrugged off .ight lead somewhere and also think that if they didn’t ignore it that it might have helped them save Dennis sooner