Nine-tenths portion of the civilized human family almost shudder at the thought of sleeping on the ground in open air; or even in a well regulated tent. “You will take your death of cold;” or get the rheumatism they will say. Such is not a fact, sleeping on the ground in the open air, with proper camping equipments is almost a cure for all the ills the human flesh is heir to.

— Col. Horace Park, The Sportsman’s Hand-Book, 1885

“I will be driving up north this weekend to visit my brother,” I informed my boss, back in about 1975. “We will be going camping,” I added.

“What’s the matter?” he asked me. “Doesn’t your brother have a spare bed?”

It seems that there are two types of people in the world—those who enjoy sleeping on the ground and those who do not.

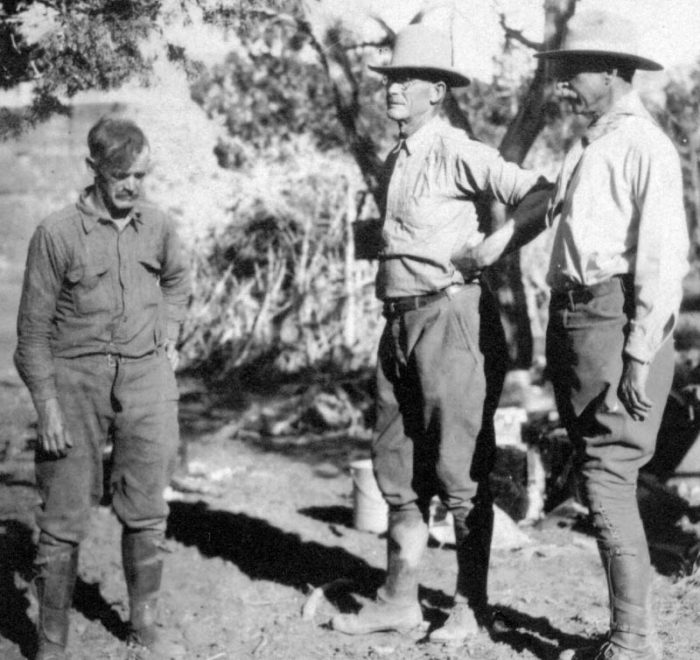

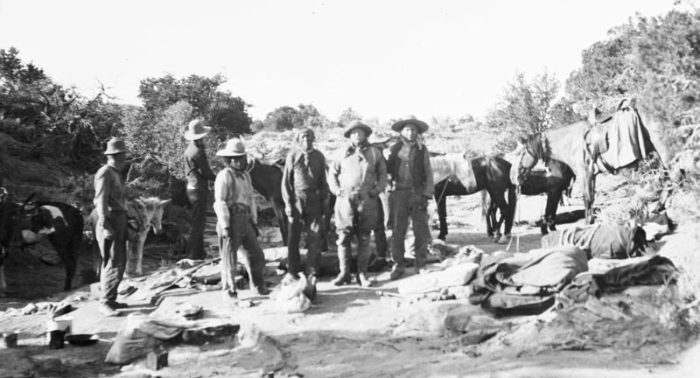

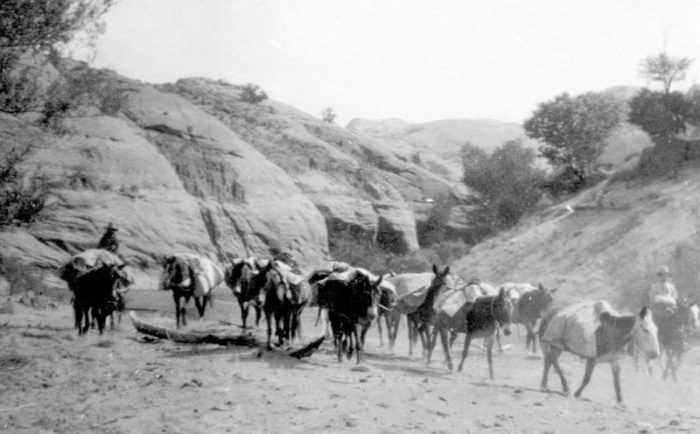

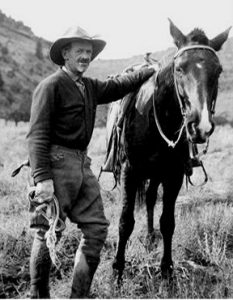

In the early years of the twentieth century, visitors to the spectacular Rainbow Natural Bridge in southern Utah reached it by an arduous, seventy-mile horse trail through extremely rugged and beautiful territory. My great-grandfather, John Wetherill, outfitted and guided most of the earliest adventurers, providing horses, pack mules, camping gear, and grub. His clients had to endure the rigors of sleeping on the ground, but most of them seemed oblivious to the associated discomforts when reflecting on the amazing glories of the scenery and salubrious rewards of spending time in the outdoors.

The canyon country explorer who left the most complete record—in photographs and journals—was Charles L. Bernheimer, the self-styled “Tenderfoot and cliff dweller from Manhattan.” (For more on him, see my article, “The Gentleman Explorer: Charles Bernheimer and his Canyon Country Explorations,” in the August/September 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr.) He was an enigma to his wealthy, citified cronies. Nearly every year from 1919 to 1930 he would leave the comforts and luxuries of his palatial New York home and head out west to engage in rugged horseback explorations of the canyon country that involved sleeping on the ground, eating meals cooked over campfires, and enduring the countless rigors of outdoor life.

If Bernheimer had any misgivings about sleeping on the ground, he avoided mentioning them in his writings. From his youth, he admired rough and tough adventurers who braved the wilds to penetrate new country. “Henry M. Stanley, David Livingston, and Humboldt fired my imagination,” he recalled. “Nansen, Sven Hedin, Greely, and Peary kept it alive. In later years the romances and exquisite descriptions of Zane Grey contributed their share toward the planning which finally led me to turn my vacations into something more substantial, to do in a small way what our big explorers and discoverers were permitted to do on a heroic scale.”

Selection of a comfortable sleeping place was a primary consideration. Ground that is uneven, rocky, tilted, damp, or subject to flooding is best avoided. Loose sand is softer than compacted soil. Bernheimer dealt with some of these matters by bringing along an inflatable mattress—a luxury that his helpers probably considered frivolous. They had conditioned themselves to sleep soundly on top of only minimal padding—perhaps a comforter or blanket. Although less cushy, their method was more reliable, avoiding the “rude awakenings” that Bernheimer sometimes experienced when his mattress sprang a leak and deflated during the night. He would then need to locate the hole and seal it, typically with pine sap and adhesive tape.

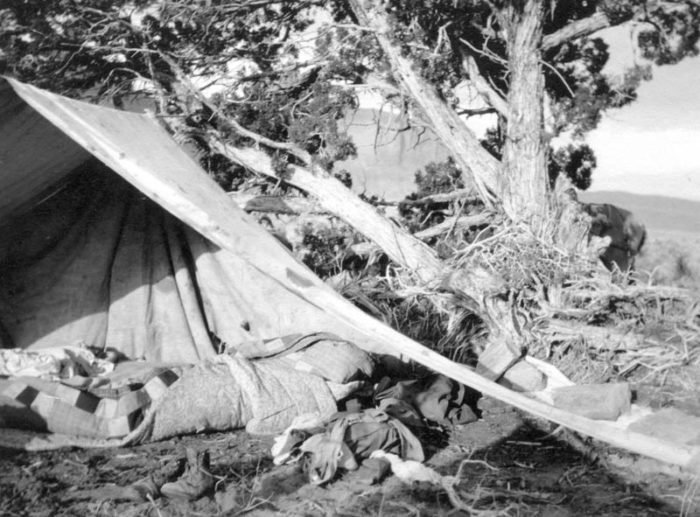

Bernheimer began his excursions in late May or early June. At that time of year, nighttime temperatures on the Colorado Plateau were sometimes bitterly cold, and winds added to the chilling effect. Although sleeping bags existed at the time, they were not commonly used on Wetherill’s camping treks. On most nippy nights a cowboy-style bedroll and perhaps a layer or two of extra clothing were adequate to ward off the cold. “Tarpaulin, quilt, woolen blanket above and below, rubber coat, overcoat all together were sufficient to keep me warm,” Bernheimer recorded on one occasion.

There was a technique for arranging the blankets to achieve maximum coziness. “To roll up in a blanket in such a way that you will stay snugly wrapped, lie down and draw the blanket over you like a coverlet, lift the legs without bending at the knee, and tuck first one edge smoothly under your legs then the other,” instructed Horace Kephart in his classic book, Camping and Woodcraft. “Lift your hips and do the same there. Fold the far end under your feet. Then wrap the free edges similarly around your shoulders one under the other. You will learn to do this without bunching, and will find yourself in a sort of cocoon.”

A tarpaulin usually served as a ground sheet and was large enough that, in the event of rain, half of it could be folded over the body as a waterproof covering. “It rained last night while we camped at Beaver Creek for about three hours,” Bernheimer wrote in his journal on one of his excursions. “Wetherill and the rest pulled their tarpaulin over their heads and let it rain. Johnson, mindful of his bunky (namely myself) stretched his tarpaulin tent style over a rope between a piñon pine […] and a shaggy old cedar. We kept perfectly dry.” In another journal entry, Bernheimer further elaborated on this technique: “It rained last night, but not very hard; but we had prepared for a real cloud burst. Johnson roped two cedar trees and threw his tarpaulin over and made our beds inside. The tarpaulin was fastened down at both ends, and the two trees protected us at the open ends. My slicker and one big sheet of rubber cloth, which by the way we always proved very useful, lay next to me for extra protection in case of a leak. My clothes were wrapped securely in another such sheet; a ditch around the tent to carry off the extra rain water provided for further emergency.”

On another occasion, Bernheimer recorded that Zeke Johnson rigged a tarpaulin vertically between two trees, in an attempt to block the wind that was blowing sand through camp.

In the absence of screened tents, bugs were sometimes a problem. “Mosquitos all night hummed the latest tango tune,” Bernheimer wrote one day. “They settled between music to refresh themselves on a scarlet liquid with a kick in and about and subsequent to it. But it seems their sting was impotent on our thick hides. It was all apprehension and no hurt.”

When the insects were even more troublesome, Bernheimer had other contingencies at his disposal. “As I am writing this I am surrounded by the odor of citronella and oil of cedar to ward off the unwelcome visits of the gnats and mosquitos,” he once recorded. On another occasion, ants invaded his bed. “My mosquito net which I carried unused for four years with me may now have to be requisitioned into service,” he suggested one time when the insects were particularly bothersome.

As modern campers well know, sitting around camp after dark and crawling into bed on a cold night can be numbing. “To brush my teeth in the semi-dark of a camp fire at 9-10 p.m., the wind blowing, the novelty of camping after a year’s molly-coddling in accustomed city surroundings, is awkward to say the least,” Bernheimer wrote on one of his trips. “Added the cold and the need to change from woolen shirt, coat and vest, bandana around the neck, overcoat to thin pajamas, sheltered through my lair was, it became a tragedy. But I did it so as to have no break in my ten years’ record of taking by this change an air bath in the absence of a watery one.”

Where wood was available, and when the wind was not blowing hard, campfires provided welcome warmth. However, they required tending if they were going to produce adequate heat throughout the night. “Johnson built a fire near by my bed to make my undressing a bit less cold,” Bernheimer once remarked. “It helped, and while my feet, too, felt warm upon retiring, they became lumps of ice soon after and stayed that way all night.”

Even more onerous than crawling into a cold bed at night is crawling out of it on a chilly morning. “Morning very cold,” Bernheimer penned one day. “It required resolution to get up, wash in ice-cold water and strip one’s night clothes. It seems that every time I get my bare skin exposed the wind puffs.” On another occasion he wrote: “To get up this morning at 5:30, when the temperature was still lower, with toes, hands, feet and fingers aching with cold, was distressing. But the breakfast of bacon, oatmeal, coffee, hot water, jam and toast beckoned and now at 8 a.m. all is well and I am none the worse.”

Bernheimer’s special provisions made for a mule-load of luggage. In addition to his extra bedding supplies, he brought along a medicine chest, a considerable wardrobe, and a stockpile of canned foods.

Bedrolls were heavy and bulky, as were the other trappings of back-country travel. This necessitated the use of horses and mules to carry the gear. Additional pack animals were then needed to lug oats, shoes, ropes, and hobbles.

Bernheimer was privileged to have the wherewithal by which to hire guides and wranglers to supply and manage his elaborate camp outfits. However, an incident during his seventh expedition inspired him to engage in some soul-searching regarding the complexity of his practices. “An Indian called for supper,” he wrote. “I asked what sleeping facilities he had and was told that all he had was the little blanket behind his saddle, the tiniest affair. He was about seventy years old, and I, sixty-two, need a rubber mattress, tarpaulin, quilt, military blanket and another woolen blanket.” Was it really worthwhile to go to the expense and trouble of accumulating and organizing a prodigious array of gear, lugging it over steep and rocky routes to camping places, repeatedly loading and unloading it, setting it up and taking it down, and dealing with high-maintenance pack animals?

One of the reasons that traditional Native Americans were content with a simpler approach is that they had conditioned themselves to withstand the cold. A Navajo man named Wolfkiller described how this ability was instilled in him from the time he was a boy.

Mother woke us at dawn. She said that it was snowing and we must go out and roll in the snow. We complained that we did not like to roll in the cold snow.

“My children, that is the reason I want you to do it. It is because it seems cold to you. The snow will be with us for several moons now, and if you roll in it and treat it as a friend, it will not seem nearly as cold to you. You have rolled in the snow every winter since you were babies. Why should you not want to do it now?”

We went out and did what Mother told us to do. It did not seem half as cold to me as it had before.

(Wolfkiller was a dear friend of John Wetherill’s wife, Louisa, and she recorded the story of his upbringing in the book Wolfkiller: Wisdom from a Nineteenth Century Navajo Shepherd. For more on him, see my article, “The Wisdom of Wolfkiller: A Nineteenth-Century Navajo Shepherd and Sage,” in the October/November 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

One noted backcountry explorer of later years, Kent Frost of Monticello, Utah, solved many of the logistical challenges that Bernheimer and others faced by dispensing with the livestock. He went afoot, carrying only the simplest of gear. His pack included no bedding at all. To stay warm, he relied on campfires that he cleverly designed to last throughout the night. “I learned to drag in the big logs when I got ready to make my fire in colder weather, like a pinyon tree or something, and then start my fire in the center of the log,” he explained. “And then when it burned in two, why then you run the two ends together, and they keep burning all night long that way.” He also slept with rocks he had heated in the fire and looked for small alcoves in which to camp that would concentrate the heat radiated by the campfire.

In cold countries, there are reportedly ascetics who, thinly clad, make their beds on snow, ice, or bare pavement. Contemporary Dutch writer Wim Hof—known as the Iceman—teaches others how to use cold-training to “create radiant, long-term health.” These advocates demonstrate that aversion to cold does not always reflect avoidance of genuine physical danger, but it sometimes has a purely psychological aspect.

Nevertheless, it might be asked why people would willingly subject themselves to disagreeable conditions associated with sleeping on the ground, such as hard surfaces, cold, wind, sandstorms, insects, and a myriad of other discomforts. For adventurers such as Bernheimer, the answer was that the deep enjoyment, gratification, insights, and physical and mental health gleaned from engagement with pristine nature make the self-imposed hardships seem inconsequential. The annoyances are only sporadic, and they are overshadowed by pleasant or even glorious experiences along the way.

Have you ever been in the midst of grand scenery when the air was deliciously fresh, calm, dry, and balmy? Have you ever slept under a starlit sky in a place unaltered by humans and beyond the reach of manmade noise? On his 1924 trip, Bernheimer described one such night.

We spent the night at Kingbird Camp, and a more glorious night I have never observed. It was neither hot nor cold, just cool enough. Clear Kaibito Creek bubbled over its pebbly bed, dropping near our camp over a ledge six inches high, and kept up a constant roar so welcome out here. The moon was almost full. Clouds there were none. The dipper was facing me in my bed. A few frogs kept up their entertaining sing-song. Mosquitoes were absent. The illumination of the rocks in a gold bronze hue was so bright that every crack and detail was visible. The sand alluvium on the other side of the brook some twenty feet high was the only straight line to relieve the curves of the sandstone pinnacles and the zigzag of their cracks. A wild bird would call occasionally. It was a peaceful night. We had retired before the afterglow of the evening sun had faded. I needed the rest and sleep but I could not resist the tempting surroundings, and kept my eyes wide open to drink in, to store up precious memories.

For Bernheimer, the primitive camping experience provided a pathway to “wonderful sights, sounds, odors, tastes and touches.” The enlivening of all of his senses made the stresses and worries of city life fade away. “The calmness that comes over one here is something akin to celestial peace,” he reflected.

On another occasion, Bernheimer described the multitude of beautiful colors within his immediate vista:

City people think of sand and rock when they pity me for coming out here. But think of a square yard of space which has growing on it a few dark blue larkspur, one pink cactus in bloom, the color of bridesmaid roses, a bunch of yellow phlox (at least this is what Wetherill thinks it is) with three deep lemon petals and an orange center, a few sagebrushes, the color we love so much in decorations, some deep green wire-grass all on a terra cotta colored earth, and a sky almost royal blue. Oh, I forgot the silver glitter of the foxtail grass. The almost black looking cedars and green-black piñon pines framed the spot, and there are endless corners like this.

Beyond stimulating a sense of wonderment, untamed nature can have a profound character-strengthening power in those who dare to leave the comforts of home and venture into the wilderness. “The desert […] conveys a sense of vastness, of timelessness, a fuller realization of man’s place in the universe. He there feels alternately humble and proud, little and big, reverent always, occupying by grace a point in the center of things,” observed Bernheimer.

One of the finest descriptions of this effect was penned by adventurer Winifred Hawkridge Dixon, who traversed the Rainbow Bridge trail in 1919.

Sleep that night was more romantically staged than under ordinary circumstances. The cold, glacial tang of high altitude nipped us pleasantly. The cliffs shut us in, not forbiddingly but protectingly. The firelight was cozy and homelike. We made a little oasis of human companionship in this wide, primeval solitude, but our spirits were high enough not to feel our isolation. Rather, we had an increased elation and sense of freedom. What myriads of people, jostling each other every day, never get more than a few feet from their kind! We had a sense of courage toward life new to us all. The mere fact of our remoteness helped us shake off layers and layers of other people’s personality and showed us new selves undreamed of.

Another benefit of sojourning in places that are devoid of beds is its potential to dispel baseless worries. “Out here where one scrapes and knocks and cuts oneself all the time, unavoidable matters connected with rough life, one must expect to have some bête noire bothering daily,” Bernheimer observed. “Forgetting is the proper attitude, or grin and bear it, or King Solomon’s dictum, ‘this will pass.’” Irrational fears are curtailed by a sharpening of the faculty that distinguishes between legitimate and imaginary risks. “Danger from snakes, scorpions, centipedes, tarantulas, and spiders, and that incidental to rock work, quicksand, riding, and climbing, if ordinary care is used, is no greater than crossing our city streets,” Bernheimer declared.

For Bernheimer and many others who ventured into that country in the early days, these lessons were solidified by their observations of Native American residents for whom the insights were second nature. “The Indian has ever known by instinct that there is harmony between himself and Nature,” wrote 1911 trekker George Wharton James. “They look with wonder upon those whites who, when thinking of camping-out, talk about the danger from snakes, tarantulas, scorpions, and the dread they have of bugs, spiders, and other creeping things. To the American Indian this attitude of mind is incomprehensible. He knows there is nothing to fear, and he lies down to sleep without a qualm in a snake-infested country, knowing that nothing will harm him or molest him.”

According to writer Robert Frothingham, who ventured along the Rainbow Trail in 1924:

[…] if there is any place on earth where a man’s real character comes out—especially if he has a yellow streak—it is the sort of wild, out-of-the-way place typified by this desert region. Camping on such trails is not only revelatory of hidden traits—it is rigid discipline for weaknesses. Self-consciousness, for instance, or petty jealousies; if you have to confess to either of these, just go out into the wilderness, make friends with a pack-horse, lie down under the open sky with your dog at your side, and take in what the desert has to say to you. Cut some wood for the cook, or keep his water-pail full. Whatever you feel like doing, or have to do on a desert camping trip will be good for your soul.

I don’t remember much about the circa 1975 camping trip with my brother, but I’m sure it was typical of the many times I have gotten away from the noisy, constructed, sanitized realm of modern society and enjoyed the primordial, awe-inspiring, natural world where my bed was on the ground. I took advantage of modern camping gear that is light enough to be carried in a backpack. Over the course of time, my basic sleeping equipment—an inflatable pad, sleeping bag, and compact tent—seemed to be more comfortable than the warm, soft bed I have at home.

By studying the values of my great-grandparents and the wisdom of their Navajo friend, Wolfkiller, as well as getting out whenever I could, my appreciation for the power of natural environments to strengthen the soul grew ever sharper. I also began to better recognize the stultifying effects on human character of relentless exposure to artificial environments.

When I came across these words written by philosopher and poet Rabindranath Tagore, known as the Bard of Bengal, they resonated most poignantly:

The west seems to take a pride in thinking that it is subduing nature; as if we are living in a hostile world where we have to wrest everything we want from an unwilling and alien arrangement of things. This sentiment is the product of the city-wall habit and training of mind. For in the city life man naturally directs the concentrated light of his mental vision upon his own life and works, and this creates an artificial dissociation between himself and the Universal Nature within whose bosom he lies.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer. Click here for more articles by Harvey Leake.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

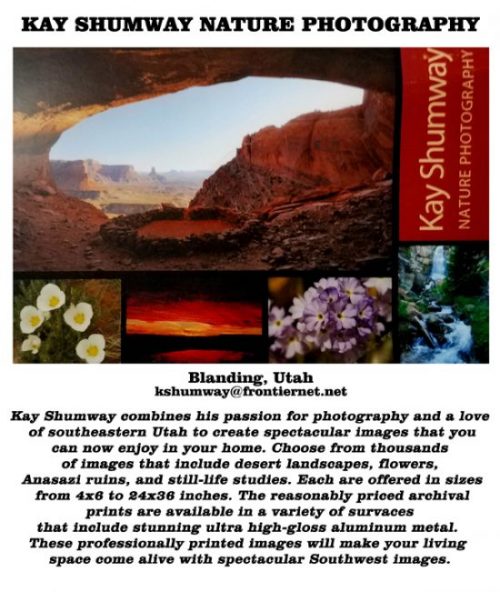

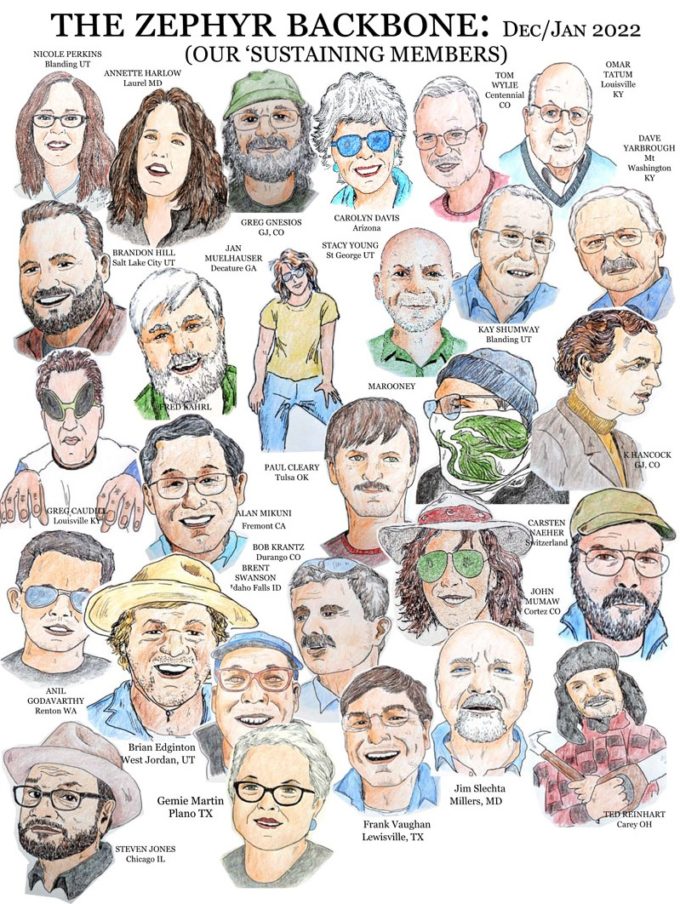

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

thanx, harvey! my present X-keyoose is that i’m (somewhat) old now, but your fun and probing and (at times) amusing essay brought back many fond me(s)mories of all the times i thought “nuthin’ weird nor unusual” about sleepin’ on the ground. one night in particular, mid-1960’s, at 12,000′ ele-vay-shun down from Mt. Rosalie (a humble 13-er south of Mts Evans & Bierstadt) i laid on my back — sleeping bag only, no pad nor nuthin’ else — marvelling at the breadth and depth of the MilkyWeigh Galaxy slowly rotating over-head, for many hours.

I enjoyed this article and can relate. My parents, sister and I camped in a small tent. There were occasions when we had the luxury of a blow-up mattress which was nothing more than what was used in the pond at the local swimming hole. These didn’t hold air for long and by the second night, we were sleeping on the ground. We went to bed in the cold and I never remember getting a good night’s sleep because I shivered all night. Crawling out of my sleeping bag wasn’t fun. Once outside the tent, my poor mother would be fixing breakfast and the water in the dish pan would be frozen as was her hands. When everything was packed up and we were ready to leave, the car didn’t provide much heat because we traveled in a VW Beetle and unless you were doing 50 or 60 mph on the interstate, heat barely trickled out. We just wrapped ourselves in a blanket. I wouldn’t give up these memories for anything. They were fun times–simple times.

I have never slept outdoors—-too old to start now!!! . My dad was a scout; and my son in law was a scout troop leader and his son, my grandson is an Eagle scout. They love to camp and travel, and do so frequently. My youngest sister and her husband do a lot of camping!!! Very nice article, and the photos are fabulous!!

I would not trade the many nights that I have slept out under the stars and inside of tents in the Grand out doors. It has been my pleasure to spend many nights on the ground with you my friend and hiking lite guru. Let’s never get soft. Lovely article, thanks for sharing this perspective.

Very nice, Harvey – always learn so much from your research and stories.