Some stories are worth an entire column; some are worth telling, but not worth the (whole) space. Here are a few of those vignettes, all of which involve first responders.

Over time as a reporter, I came to realize just how dependent the Moab community was on volunteers. Anyone who was sick or injured could expect to be treated and transported by volunteer EMTs for the Grand County Ambulance Service., under the direction of then-high-school-Coach Glen Richeson.

All the crew members had to pay for their own training and certification, which included stints at St. Mary’s Hospital ER in Grand Junction.

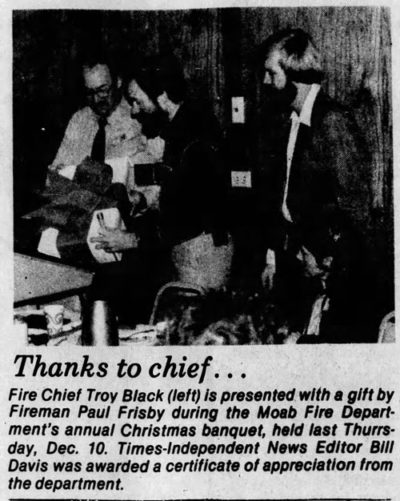

The fire department was also all-volunteer, with the exception of Chief Troy Black, who I introduced in the April/May 2021 Zephyr issue in the Doxol fire story.

All department members participated in training exercises and weekly meetings.

When I first arrived in town, I felt the volunteer services and local law enforcement could use more coverage, with photos, so county taxpayers could see where their money was spent; in addition, I figured local first responders, both paid and unpaid, would get some recognition for their efforts.

It was with that concept in mind that I once nearly killed a substantial number of the fire department’s volunteers, along with Chief Black. Of course, that wasn’t the intended goal. . .

Smoking and BEV

I don’t know how commonplace this response is among other people who have to get up and function during the middle of the night, but over the years I developed what I called “Bright-Eyed Vapidity,” henceforth to be known as “BEV.”

BEV was a survival technique: In a night located between two always-busy days, one should only have to waken to the level required to get the job done.

With BEV, one could perform as if conscious—ask a few questions, say, or take a couple of pictures—all without truly waking up. This method worked only as long as no one asked you to do anything complicated: think., for instance, or notice the world around you.

In an extreme example, this condition once resulted in me “waking up” in my car, northbound at some ridiculous hour, camera bag in hand, knowing I was going to a fire somewhere in that direction. Sure enough, a block north of Center, the trucks were there, on Main, just as I knew they would be. The call, fortunately, proved to be a false alarm.

I have no memory of waking up, hearing the fire call, noting the address, dressing, leaving the apartment, starting the car, and driving off. That’s BEV.

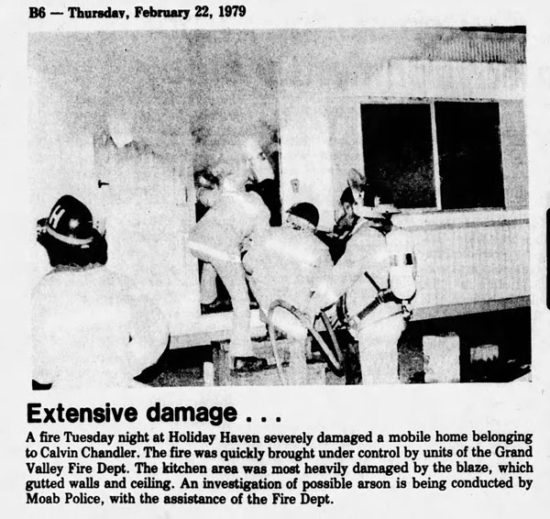

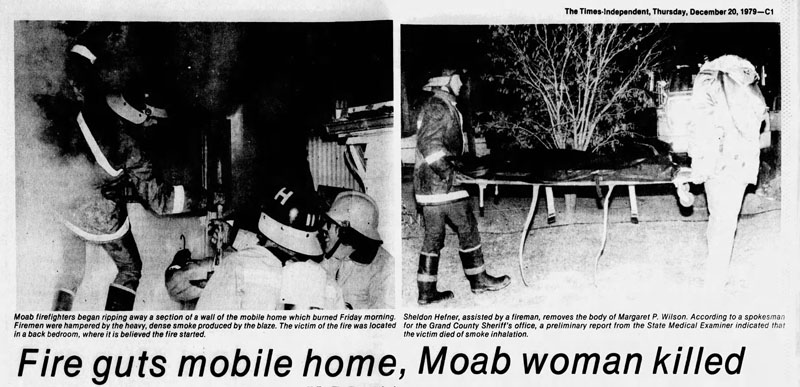

February 20, 1979, also proved to be a BEV evening. This time I remember the call, a mobile home fire at Holiday Haven. Trailers, especially older single-wides, tended to burn quickly and intensely.

Firefighters were always concerned about possible trapped occupants in mobile home fires, and would sometimes push limits in searching for victims. When I arrived at the scene, involving an older, single-wide unit, a firefighter at the nozzle of a hoseline, was about to open the door. I set up to shoot.

He opened the door and stepped in, allowing fresh oxygen into the fire. The flames whooshed, knocking the lead firefighter onto his back. I thought for a second I was taking pictures of a man’s death, but the flames died down quickly and he hopped up, taking control of the nozzle. Additional crews were able to knock the fire down within minutes.

I hadn’t been inside the trailer, as it seemed a routine fire, so took a few more shots then headed to the car, lighting my post-fire cigarette. At that time, I was a fairly heavy smoker, so practically everything was a trigger to light up: fires, accidents, deadlines, and, most especially, telephone calls.

On the drive home, I heard my name on the scanner’s fire department channel—unusual in the extreme:

“Bill Davis,” said Chief Troy’s flat, radio monotone, “if you can hear this, please return to the fire scene.”

What the hell? I hadn’t been fully awake, but I didn’t think I’d done anything illegal or prominently stupid.

I turned around, mystified, and drove back. Outside, a couple of firefighters were rolling up hose.

“Hey,” I asked, “Any idea where Troy is?”

He nodded toward the trailer, “In back, in the bedroom.”

I climbed into the mobile home through the doorway where the first-in firefighter had been blown flat; I was surprised how little damage had been done. The carpet was sopping from the thousands of gallons of water sprayed on the inside, but the only furniture, a fancy, single-unit entertainment center, was hardly scorched.

At this point, a normal person would be figuring some things out. Not me. I ambled through the kitchen, really splashing now, and cursing once again my failure to carry boots. My running shoes were soaked.

In the kitchen, I passed an open closet door; several items were melted on the floor, include the remains of a one-gallon plastic gas can. Again, the normal, waking human being would have it figured for sure now. Not the BEVed photographer, as I stepped, still squishing, over a row of now-extinguished candles across the hallway.

“Now,” the me of today says, “that’s not just BEV; that’s stupid.”

The me of yesterday followed the sound of voices to a back bedroom. The main bedroom, I could see in passing, contained only a waterbed. Something was finally sinking into my brain.

“This doesn’t look right.”

Troy glanced up as I entered the tiny bedroom and gestured toward the closet, “Can you get a picture of that?”

I looked at the white plastic cube container on the floor.

“Sure.”

“No,” Troy pointed to a thin stream of liquid flowing onto the floor from a knife cut, “can you get a picture of that?”

A light at last began to dawn: candles, accelerants, near-empty trailer. . .

“You might want to watch that cigarette,” came the mild voice of a firefighter over my shoulder.

“You’re standing in two inches of gasoline,” he added.

Gark.

Well, we’re certainly wide awake now, aren’t we?

The firefighter spoke again, quietly, “I’ll cup my hands and you can crush it out in my gloves.”

One would think a sense of self-preservation would have sent the other half-dozen or so volunteers diving for the windows and doors. Not so. They all circled around the firefighter’s gloved hands, heads bent like monks in contemplation, as I carefully, oh so carefully, crushed the butt against the rough-out leather.

The line of monks, myself included, followed the gloved firefighter to an outside door, where we watched him scatter the ashes to the stars and a cool breeze.

Once I stopped shaking, I concentrated on getting the sharpest, best-exposed fire scene shots anyone has ever seen. The knife slit appeared as a veritable waterfall of gasoline. Investigators couldn’t place the trailer owner in town the night of the fire, but I later heard the insurance claim was rejected. The state fire marshal complimented Troy on the quality of the fire scene photos.

I also learned to never enter a fire scene with a lit cigarette.

It was from this encounter I developed my apparently lifelong hatred of arson, and again became reacquainted with an intense dislike of making stupid mistakes.

When a first responder makes a rookie error that might get someone hurt or killed, fellow members of the group, whether firefighters, EMTs or cops, tend to be merciless on the offender, as well they should be. Make a stupid enough mistake and you’ll never hear the end of it.

No one on the department, then or thereafter, ever mentioned the incident to me again. I don’t know what that means.

I didn’t quit smoking for several more years, however. Nerves, I suppose.

Drugs and/or Alternate Realities

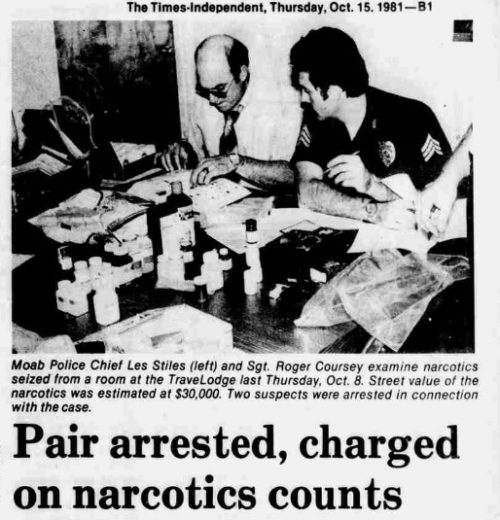

It sounded like an episode of the “Cops” TV series. The Moab Police Department had received information someone, apparently connected with the burglary of a pharmacy in Wyoming, had set up shop in a room at the Travelodge near the high school, and was dealing hard drugs. Following an investigation, the cops asked for and got a search warrant.

On Oct. 8, 1981, I got an invitation to go along on a bust of the room. Then-Chief Lester Stiles (No relation to Jim, but people joked about it a lot) liked to “handle” the media when something was afoot. I was not a fan of being handled.

During a previous bust, local TV personality Les Erbes and I were isolated with Stiles in his car a couple of blocks from the scene on Westwood. This was inconvenient, as my house was only a couple of doors up from the suspect’s place.

I could have covered the bust more effectively from my living room with my feet up on the couch. The take from that particular search was the tiny remains of a single roach.

In the October ’81 double bust, the main suspect was stopped in his van nearby. Meanwhile, a collection of cops with a passkey, and one local reporter, entered the suspect’s room through a connecting door.

Spread out around the room was a positively stupefying collection of heavy pharmaceutical drugs, including large bottles of artificial opiates, most in their original commercial packaging.

The list of samples later tested by the state included Demerol, Nembutol, morphine sulphate, Tylox, Benzedrine, Demerol hydrochloride, Prelude, Percocet Dexamyl, Dexedrine, Darvon Placidyl. Click Here to read the original story.

And so the list would be complete: a small quantity of marijuana was mentioned, which seemed quaint, given the variety of dangerous narcotics scattered around the room.

The collection also included the only official container of pharmaceutical cocaine I’ve ever seen: a brown glass bottle with a plain white label, which said “Cocaine,” sure enough, in bright red letters. At the time, the stuff was sometimes used in eye surgeries; I’ve no idea if it still is.

I mention all of the above to illustrate the likely winner of the Coolest, Most-Controlled Reaction of the Decade Award: the suspect’s girlfriend, who, upon stepping out of the bathroom, perused the crowd occupying her bedroom and asked archly:

“Do you mind if I put on some clothes?”

The pair was arrested and multiple charges filed. However, in what I would later use as a classroom example of “court reality” versus “non-court reality,” (court-admissible evidence versus “Yeah, but everybody knows”), the District Court, in a suppression hearing, did just that to the police department’s search warrant, due to lack of evidence.

This meant, using the “fruit from the poisoned tree” analogy familiar to law students, nothing obtained during the warrant search could be used as evidence, i.e.: everything in the local case. Charges had to be dismissed.

In my later career as a professor, this case always sparked a lively classroom discussion of constitutional rights versus “yeah but”s of common sense, and how a room full of dangerous prescription drugs could disappear from the eyes of a court.

The case also illustrated chutzpah, as one of the officers said the suspect asked for the drugs back when he was cut loose.

I wonder if it’s entrapment if the cops give a suspect illegal drugs when it’s at his own insistence?

Instead, he got a lecture on why a police department was not about to dispense a pharmacy’s worth of drugs to a citizen. The suspect still faced potential legal entanglements with the State of Wyoming.

The female half of the pair was also busted for trying to smuggle controlled substances to her boyfriend in Grand County Jail.

I wondered if the suspect had been sampling any of his products (the arrest of the smuggling girlfriend made that possible), as most of the drugs recovered from the room were powerfully addictive. Anyone using, suddenly cut off, would have a lengthy unpleasant experience.

A Mayberry Mystery

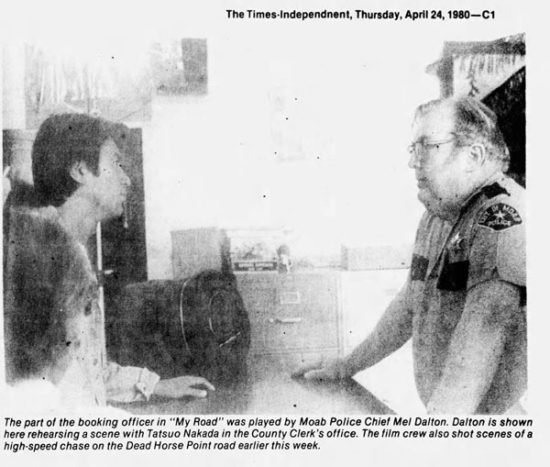

My final offering is so small-town it’s practically worthy of Andy of Mayberry. This is Moab in the late 70s, early 80s. Mel Dalton was still police chief.

One morning I overheard a scanner call directing “2T-1”—the chief—to a burglary at Ray Tibbetts’ Family Budget clothing store on the northwest corner of Center and Main. I didn’t have anything going, so I wandered on foot the half-block from The Times office to the store.

I noticed upon approaching the door, a glass panel had apparently been kicked out, and there was a fair amount of blood on the floor, smeared with bare footprints. Mel showed me a chair in the shoe department with a pool of blood on the floor below.

The suspect had been shopping for shoes way after the need had been established. Of course, if she (It turned out to be a she) hadn’t kicked the front glass, then the protection of feet wouldn’t have been an issue. Life in Moab 40 years ago sometimes moved in mystical circles like that.

After Mel finished dusting the chair for prints, he decided to follow the bloody footprints back out the door, detective fashion.

The footprints initially led to a local watering hole on First West, where, after a pause to regroup and refresh, the suspect again left bloody footprints bound north for—her house. The subject proved to be well known to the Moab P.D.

Mel followed the trail and affected the arrest without incident: the morning’s mystery successfully closed before lunchtime.

Okay, so the incident might not have been Mayberry (or Sherlock), but for the real world, it was close enough, and a reminder that not all things are complicated.

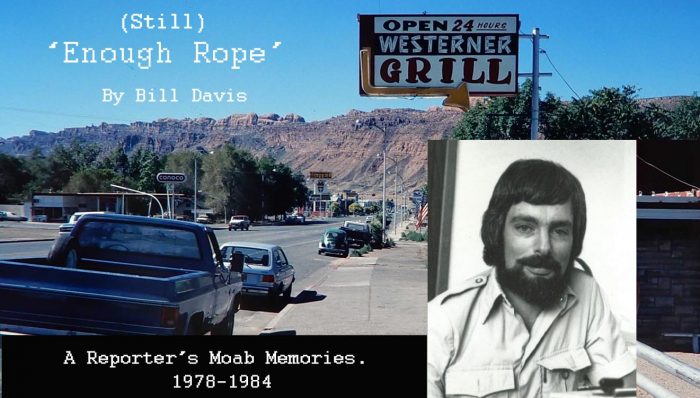

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!