Almost 35 years ago, I wrote a short article about my Moab neighbor, Marilee “Toots” McDougald. It appeared in the very first issue of The Zephyr and was based on a taped interview with Toots, earlier that spring. Recently I re-discovered that old cassette tape and realized that it was almost two hours long and that the story I later wrote had left out many details of this amazing woman’s life. So I went back to the tape and re-wrote the story. Here is a much more complete account of the life of Toots McDougald…JS

Her name was “Toots McDougald.” If you tried to call her by any other name, you did so at your own peril. Officially she was born “Helen Marilee Walker” on September 15, 1915 and her parents wanted to call her Marilee, but it was hopeless. By the 1940s, even the Moab phone company listed “Marilee McDougald” as TOOTS in its annual updated phonebook. Of course, in those days, when the population of Moab was about 600 and during a time when there was still a personal touch to life among humans, the local phone company folks knew Toots, knew that nobody would know who the hell “Marilee McDougald” was, and willingly listed her in their little phone directory for the Toots she really was. Decades later it was one of the great blessings of my life to say that Toots McDougald was once my neighbor and my friend. And had I been 30 years younger, maybe a lot more—I’ll explain in a minute.

I came to meet Toots on a cold afternoon in March 1985. Moab was in the depths of its worst economic crisis. The uranium industry had collapsed and the Atlas plant shut down. Longtime residents were fleeing in droves and real estate prices plummeted. But for me, for the first time in my life, I could afford the $20,000 needed to buy a home. I’d just placed a down payment on a little stucco bungalow on Locust Lane and now I stood in the remnants of what passed for a yard. I surveyed the damage.

Suddenly a gravelly deep voice came at me from over my shoulder. “Are you buying that house or just renting it?” Until I turned around, I wasn’t sure if I was hearing a man or a woman. Whoever it was sounded annoyed.

Behind me stood a striking figure of a woman. She was leaning against a fence post — a tall woman, thin as a rail, sort of gangly, with short gray, slicked-back hair. A cigarette dangled casually from the corner of her mouth. She eyed me warily and waited for the answer she wanted to hear.

Finally I replied, a bit uncertainly, “Well…for better or worse, I bought it,”

Toots gazed at me a moment, then pinched the butt from her mouth and used it as a pointer. “You see that aluminum roof up there ? Your roof that is.”

I turned for a better view. Sure enough, I had not noticed that my roof was actually constructed of aluminum shingles. I’d never seen anything quite like it. But they did look a bit worn.

Toots said, “Look at that glare. Look at the light shining off that damn roof. I hope you paint it a nice darker color, because the glare from it in my kitchen is awful.”

She glanced at the glittering reflective nuisance of a roof once more, shook her head, and went back inside. I looked at the roof again and decided this was not a woman I wanted to get off to a bad start with. The next day I bought four gallons of flat, brick red, aluminum paint and got rid of the glare on “that damn roof.” Toots and I became instant friends.

***

For most of the 20th Century, Toots McDougald was a Moab institution. She was born in Moab, in the same house on First North that the Ron Pierce Family still lives in today. Her grandfather, M.R. Walker, built it around the turn of the century.

Toots grew up in and around Moab, but spent some time in Thompson and Cisco, where her mother cooked in a hotel. As to her lifelong moniker, Toots claims that a man named Albert “Ab” Wats, whose sister was married to the longtime publisher of the Moab Times-Independent, Bish Taylor (Sam Taylor’s dad) gave her the nickname. Ab spent a lot of time with her family and quickly grew fond of this energetic little girl. One day, as the little girl performed amazing feats of skill on the front porch swing, Ab grinned proudly and proclaimed, “You’ll always be my little Tootsie-Wootsie.” Over time, Tootsie was abbreviated to Toots and the name stuck. By the time Toots was in school, nobody knew who Marilee was, although two teachers at her grad school, years later, Miss Penfield and Miss Peterson insisted on calling her by “her proper name.”

“That always bugged the hell out of me,” remembered Toots. “It’s a good thing the phone company wasn’t bullheaded like those two…without the ‘Toots’ in there, I’d never get any calls.”

GROWING UP MOAB…1920S STYLE

In the 1990s, when Toots was in her mid-70s, she still possessed an almost encyclopedic memory of her life. What was it like, growing up in Moab in the 1920s? Toots remembered everything…

“It was wonderful. We went on picnics and hikes and chicken fries. We had great watermelon busts, in fact, a man named Ollie Rearden planted a field of melons, just for us kids to steal. He said we could steal from that patch all we wanted, if we left his patch alone.

“We’d go over the Lion’s Back, clear to the river. We jumped a crack once, and we decided to come back the same way. When we got the crack, it was twice as wide as before. Some fisherman across the river kept yelling, ‘Don’t jump!’ but we did anyway. That was Madge Duncan and Maxine Foster and me….Everything was so free and easy, no pressures, no traffic. We didn’t know anything about drugs. We thought we were pretty wild if we got a sip of homemade beer…My father’s friend was a bootlegger.”

And who was that?

“I’m not saying.”

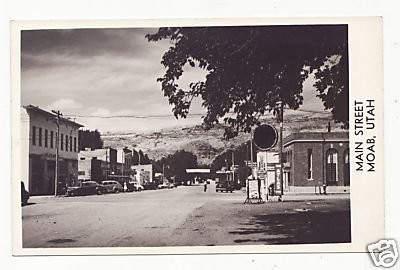

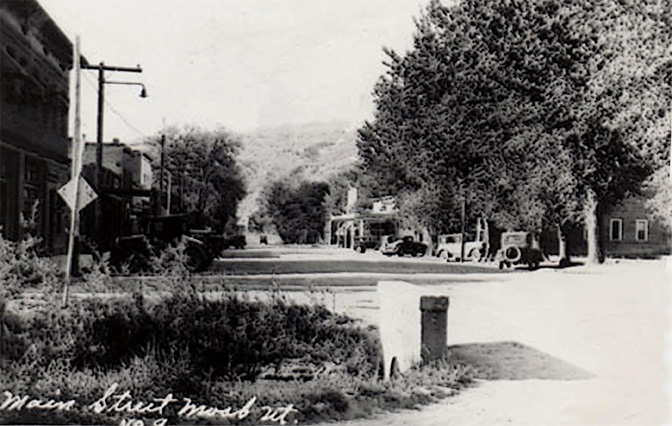

Even in 1989, Moab had changed dramatically since those lazy quiet times, almost three-quarters of a century before. In those days, Main Street ended at Center Street. Until the 1950s and the uranium boom, the main southbound road turned left at Center, then right at 400 East to Mill Creek Drive. Swannie Park, remembered Toots, “was the Grand County fairgrounds. There were grandstands and corrals and bucking shoots. Before, that whole area was a swamp–just a grassy, murky area. The first fairgrounds were where the baseball fields are today.”

And here, according to Toots, is where Moab’s dreaded plague of goatheads first established a beachhead. “As I recall, we’d get circuses in here and rodeos, and a lot of the time, these people would bring their own hay and feed for the animals. Well, that stuff must’ve been mixed up with the hay, because pretty soon those nasty little goatheads were popping up everywhere. I’ve got no use for goatheads at all.”

As bucolic as Moab could be, the town had its traumatic moments as well. Toots found herself in the middle of a particularly dangerous situation when she was just ten or twelve. “I was living on Center Street then, across from Star Hall. One day, I was out on the front porch when I heard these shots coming from the jail. I thought for sure it was a breakout, and that they’d shot the locks off the door. I saw a guy running, and so I ran over to the jail and found the sheriff, Dick Westwood, dead. My friend Helen Foster was walking along the other side of the street at the time, and the man who shot Dick ran right past her, with the gun in his hand.

“There was quite a search. Albert Beech was coming from Monticello when he spotted him. Albert captured the man and hauled him into town, holding an unloaded .22 rifle on the guy the whole time…of course, the guy didn’t know that.”

But most of the time, life was peaceful, beautiful, and simple.

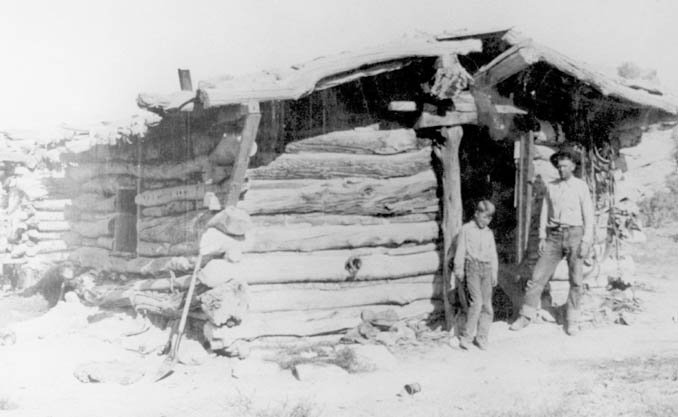

FOR TOOTS IT WAS STILL “TURNBOW CABIN”

For several years, Toots spent her summers in what would later become Arches National Monument, at a place now named Wolfe Ranch, for its first inhabitant. But in those days, Toots and everybody else steadfastly called it Turnbow Cabin. Her stepdad was Marv Turnbow, a prominent rancher in the 1920s and 30s and later the first custodian of the newly formed monument. It was Turnbow, in fact, who filed the first homestead papers on the ranch around 1915, just years after John Wesley Wolfe moved back to Ohio. In 1989, Toots and I returned to Turnbow cabin. Naturally Toots remembered just about everything…

“We used to leave Moab in the morning on horses and ride up Courthouse Wash for five or six miles. There was a good horse trail that would lead up to Balanced Rock and down to Salt Valley and the cabin. Of course, you couldn’t ride a wagon on it….And we’d bring most of our food. We’d bring canned milk, and to this day I can drink canned milk right out of the can. And flour and salt and coffee, and things Mother canned. We couldn’t keep chickens out there or the coyotes would eat them.”

At the cabin, Toots was struck by the throngs of tourists who wandered about the place, taking pictures but barely appreciating the memories and stories tucked away in the dusty corners and cracks. Toots remembered. She remembered the old fruit trees near the cabin that were still there in the 20s, but which have long since withered and died. Also gone was the corn crib, built on stilts and placed in water-filled coffee cans to keep out or drown any rodents that tried to get in. But Toots marveled at how well the cabin itself had survived. The same massive center beam, “still, the biggest, straightest juniper log I’ve ever seen,” holds up the slightly sagging roof.

The family stayed two to three weeks at a time during the summer. Marv hauled water on horseback in big metal cans from a spring just upstream from the homestead and often Toots rode with Marv to round up new calves. The chore of branding hurt Toots almost as much as it did the calf. “He’d rope one of them and I’d take the rope and wrap it around my saddle horn. Dad would jump off his horse and throw the calf down and tie off its legs. In the meantime, we’d built a fire and got the iron red hot. Then he’d dehorn it and earmark it and brand it. And the little things would cry and run their tongues out half a city block. Meanwhile, I sat on my horse and cried. Every time Dad branded, I cried.”

Once, while driving cattle up Salt Wash, Toots and Marv came to a place where the horse would have to jump. “Dad didn’t want me on the horse when it jumped, so he scooped me off and sat me on a ledge. All of a sudden he grabbed me back. Well, there was a big rattlesnake right there between my feet…it had 14 rattles on it.”

In the evenings, Marv demonstrated the art of making flour sack biscuits. “He never used a pan. He’d roll up the sleeves of his long-handled underwear which he wore year-round. He’d scrub his hands and he’d get this sack and roll the top down and make a hole in the flour and smooth it out just like a bowl. Then he’d put in some baking powder, some salt and some shortening and mix it all around. Then he’d start adding water, a little drop at a time, and just keep working it with his hand. When he got enough he’d pinch it off and when he was through, you couldn’t find one lump left in that flour sack.”

Before going to bed at night, they’d always turn the horses loose; they never hobbled them. The horses were something that Marv Turnbow took great pride in and which Toots always remembered.

“He curried and combed his horses and trimmed their tails and manes. he took beautiful care of them…they never looked scroungy, ever.”

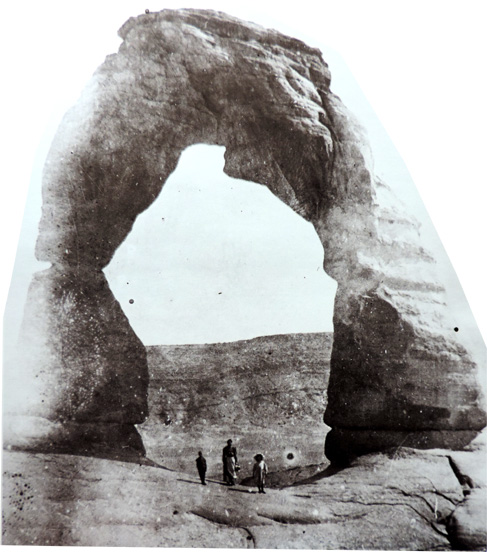

A mile north of the cabin is Delicate Arch, perhaps the most photographed and visited natural arch in the world. Seventy-five years ago, Toots had it all to herself. “We used to horseback ride up to the arch. We never saw anybody except other cattlemen from time to time. Jim Westwood had some cattle out here someplace and a man named Frank Graham did too.

“Back then, we called the arch Bessie’s Bloomers. When they made it into a National Monument, they didn’t think that was quite the name to have on it, so they gave it the name Delicate Arch. But I believe Bish Taylor is the one who brought up Bessie’s Bloomers.

“I used to call it the Old Man’s Pants, because it looked to me like they cut off the top part of a man off, and left the feet and legs.”

In the late 1930s, after the monument boundaries had been greatly enlarged, the National Park Service needed a custodian to keep an eye on this recent addition to the park system. They hired Marv Turnbow.

“In those days they had what they called ‘dollar-a-year men.’ It was sort of an honorary position and so that’s what Dad got–he became the first custodian of Arches National Monument.”

We got ready to leave Turnbow Cabin for the 30 minute drive back to town, but Toots wanted to take one last look inside her old home away from home. The walls were a lot dustier than they used to be. Most of the furniture was gone. The floor was covered with dirt and mouse droppings and gum wrappers. But despite the changes they were the same walls, and it was the same floor, the same wind-blasted, sun-baked cabin that Toots looked forward to seeing after a long, hot horseback ride, 65 years before.

Toots shook her head and smiled. “I hardly know anybody that’s lived like me, and I’m the luckiest person in the world.”

We watched the tourists heading back to their cars and trailers and motorhomes, back to the cities and civilization. As we drove back to Moab, Toots wanted to talk about the love of her life.

THE LOVE OF HER LIFE—DICK WRIGHT…

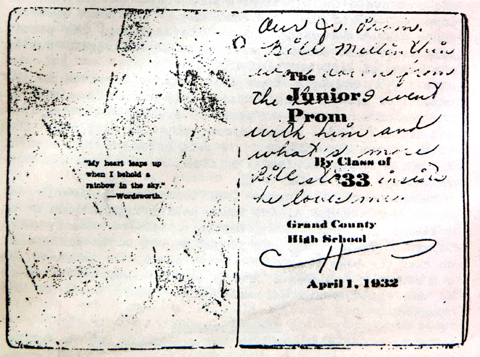

Toots spent summers at the ranch until she decided she “was too big to be cowboyin’ anymore.” Toots still vividly recalls her Junior Prom of 1932. “We decorated a hall where the Energy Building is now. It burned down a long time ago. But back then, they had movies in there, and after the movie was over, we’d push back the benches and have a dance.

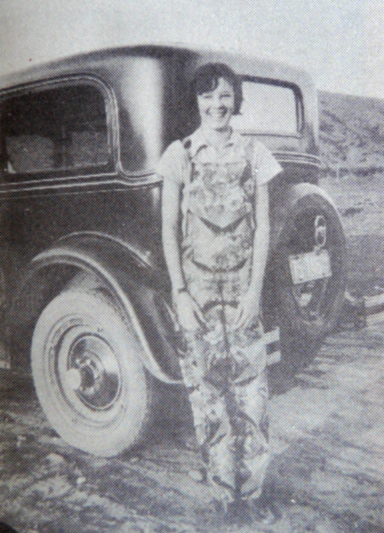

“For the Prom, and other dances too, we’d have a band. They’d play jazz and waltzes. We had great Charleston contests. I still remember the parade of the Junior Class…the promenade of the Juniors. I marched with Jim Winbourn. It was really something to get dressed up in a prom dress. In fact, we thought we were really something if we had store bought clothes. My Aunt Ida made most of my clothes. I had one pair of overalls made out of Cretone, a drapery material.”

How do you spell that, Toots?

“C-r-e-t-o-n-e; I think. I haven’t had to spell that in about a hundred and fifty years.”

And it was during one of those glorious evenings that she met the love of her life. His name was Dick Wright and his family ran a small mining company. In fact, they were among the first uranium miners in southeast Utah, though nobody at the time understood its ultimate deadly potential. Toots remembered, “At the time, we thought it was used in paint and to make our wrist watches glow in the dark.”

“If there was ever ‘love at first sight,’ it was the way I felt when I laid eyes on Dick,” Toots recalled. “He was the best looking man I ever saw.” They had gone to the 1932 Junior Prom together and from that moment on, Dick Wright was her life. She would have graduated from high school in May 1933, but Dick was headed out to the Yellow Cat Mining district that spring and Toots was determined to go with him. Her mother begged her to stay just one more month so she could get her degree, but being with Dick meant more to her than a diploma. They were married on April 6, 1933 and they spent their honeymoon looking for uranium.

Just a month earlier, Franklin D. Roosevelt had been sworn in as president, in the very deepest depths of the Great Depression. The country was struggling to keep its head above water, but Toots barely noticed. “I was so damn happy with Dick, I hardly even noticed the Depression. When you’re that happy, nothing can hurt you.” For most of the 1930s, she and Dick lived on site at various mines north of Moab. “You could say we camped out for a decade or so.”

The Wright family, including several of Dick’s brothers, worked and lived together through many of those hard years. Wherever they mined, they found a way to make a home. Toots remembered that they’d find an old shack nearby, fix it up, cover the windows and make it comfortable. She loved every minute of it. Sometimes they lived out of a tent. And she especially remembered a small cabin they built completely out of abandoned railroad ties. “It was the most solid house I ever lived in, including the one I live in now,” Toots remembered. “In fact,” she added, “I’d bet it’s standing.” And she was right.

But there were also heartbreaks to endure. Just a year after they got married, Toots gave birth to a son, Darwin Dick Wright, but the boy was unhealthy from the moment he was born and only survived a few days. Four years later, they tried again. Sammy was born in 1937 but only lived to the age of four. It was a loss that was only made bearable by the love that Toots and Dick had for each other.

In 1940, Toots suffered another devastating loss. Her stepdad, Marv Turnbow had been invited for a drive in his friend’s brand new car. Don Loveridge was eager to show off the speed of his sedan and asked Marv and another friend,Ed Kirby, to go for a spin. They were headed out of town, when Don lost control near the Mill Creek bridge and crashed into an embankment. The car rolled onto its roof and crushed Marv. Loveridgeand Kirby walked away from it, but Turnbow had suffered terrible head injuries. Toots later remembered that it was Helen M. Knight who came to the house in Moab where Toots had been visiting. She gave Toots the bad news. Marv was still alive but barely conscious by the time Toots got to the hospital. “I remember seeing him all beat up. His eyes were open and he was looking right at me, but I could tell he couldn’t see me.” Marv Turnbow lived 14 hours before succumbing to his injuries.

***

By the summer of 1941, the war in Europe had seen Germany conquer most of it and Americans wondered how long they could stay out of it. Toots and Dick and the Wright family continued to work the mines across southeast Utah in search of uranium, and were puzzled by the sudden interest in the radioactive ore from the United States government. Toots still thought its only value was as a paint additive—why would the War department be interested in it was beyond her. But the Wrights were good producers and their monthly take was so impressive that Dick and his brothers were given exemptions from the military draft. Toots still remembered that release from their military obligation raised a few eyebrows from a few Moab citizens. None of them, not even Toots and Dick, understood the significance of their work.

They worked mines in the Yellow Cat mining district north of Arches National Monument, but their prospecting extended to remote locations like Squaw Park and Polar Mesa. They even wandered into the Dove Creek area just east of the Utah/Colorado state line. After December 7, 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, their work intensified, though at the time, they failed to see a connection.

Two years into the war, in 1943, Toots discovered she was pregnant again; those nine months must have been a terrifying time for her and Dick. But happily, she gave birth to a healthy happy little girl that they named Suzanne. It was a blessing in the midst of a world war.

THE BEST & WORST OF TIMES

Until August 6, 1945, when the first atomic bomb exploded over the Japanese city of Hiroshima, neither Toots nor Dick, nor the Wright family, nor anyone involved in the mining of uranium or vanadium understood its value or ultimate use. They knew the ore was highly sought after by the United States government but nobody knew why. A second bomb, three days later, was detonated over Nagasaki. Within a week, the Japanese finally surrendered. The war was over but the demand for uranium increased.

Even before the German surrender in May, America had found itself at odds with the Soviet Union and its post-war ambitions. Now as Stalin moved to control much of eastern Europe, the United States feared another war was inevitable. But only America possessed the secret to the atomic bomb; no country could possibly challenge a nation with that kind of military superiority. It would take decades, the Truman administration argued, for the Soviets to create a bomb of ther own. But less than four years later, Russia detonated its own nuclear bomb and the world would never be the same.

Consequently, the United States pushed forward with an accelerated nuclear arms program and demand for the radioactive ore increased dramatically. Price guarantees by the government created a mining boom in the West that was unprecedented. Though many were already debating the moral implications of nuclear warfare, the mining industry boomed like never before.

For Dick Wright and Toots, it meant job security. In the late 1940s, a uranium processing mill had been constructed at Uravan in far western Colorado. With skyrocketing uranium prices, the boom brought the Wrights to the region and Dick went to work in a mine near Carpenter Ridge. The work could be dangerous, but the pay was good. The Wright Family looked forward to a prosperous future.

But on the morning of March 30, 1951, Toots woke up feeling troubled and anxious. She was worried about Dick and had felt exactly this way once before. Two years earlier, Toots had been haunted by a premonition that something had gone wrong—that something had happened to Dick— but she dismissed her worries and went about her day. Later that afternoon, she learned that Dick had been severely injured in a mine accident that had left him with two broken legs. It took time to heal, but Dick was able to return to work a few months later.

Now on this cold March morning, she was struck by the same sense of doom. This time she was determined to pay attention to her feelings. Her daughter Suzanne was about to leave for school but Toots grabbed her and said, “Not today, we’ve got to go see your dad.” They left town and headed for Carpenter Ridge. Dick was underground in a mine that should have been properly braced and protected. The props were just seven feet apart, but Toots was less than a mile and a half from the mine entrance when a slab of rock, between the two braces, broke loose from the ceiling. It fell directly upon Dick’s back, crushing him. He died instantly. Dick was only 41 years old.

Toots arrived on the scene within minutes; miners led her to Dick. They had managed to break up the slab and remove him from the debris and laid him on his back. Toots recalled, “He was still warm…I got there that quick.” Her premonition had come to her an hour before the collapse.

Dick’s body was brought to Moab and a funeral was held at the LDS chapel under the direction of Bishop Carl Mecham. Dick was well-known and well-liked by many friends across the Colorado Plateau; hundreds attended the service. He and Toots had been married for 18 years. They would be the happiest of her life.

* * * *

Toots and Suzanne moved back to Moab and for a year they lived with her mother. But in October 1952, she decided to remarry. D.C. McDougald was a longtime Moabite and brother to the future mayor, Ken McDougald. They built a small home on Locust Lane, which in those days was on the far southern outskirts of the town. But for Toots, it just wasn’t the same. Her heart would always belong to Dick and after a few years Toots and D.C. divorced. For years Toots worked several jobs to keep them financially secure. She started the Moki Trading Post in the 1960s and for years worked for Fred Stoye at his insurance agency on Center Street. She never completely recovered from Dick’s death but she never allowed herself to wallow in her own grief. Toots was too full of life for that.

NEIGHBORS

And then, in the Spring of 1985, I showed up and became Toot’s next door neighbor. My little bungalow was built in 1951. Years later, I discovered that the first owner had lined the attic rafters with newspapers to provide a very thin layer of insulation. They were all dated from the late summer of 1951. As I moved across the attic floor, I was able to track the progress of the National League pennant race via the old sports pages of the Deseret News (The Giants beat the Dodgers in a one game playoff when Bobby Thompson hit his “shot heard round the world” home run. Toot’s home was constructed the following year.

Painting my shiny aluminum roof was one of the wisest gestures I’ve ever made. Toots made a point of commending me for my paint job and she decided I wasn’t some “damn hippie” after all. It was the beginning of a great friendship. I can’t count the hours she and I spent standing at the fence, talking about our lives, the weather, and the history of Moab, of which she had plenty to share. She had another obsession. She didn’t like weeds. She loathed goatheads and held cheat grass in low regard as well. She was diligent about her own yard. One would be hard pressed to find a single noxious weed on her own property. But I had a tendency to assume that anything green must be okay and that didn’t set well with Toots. She’d complain about the invasive vegetation and I sometimes dodged her.

But then she came upon a technique to inspire me that worked every time, whether I wanted it to or not. Toots called me regularly on the phone and it would always go like this…

“Jim, this is Toots…do you like chocolate cake?”

“Sure,” I’d say and she’d tell me to meet her at the fence. I’d find her waiting for me, cake in hand, but just as I’d start to reach for it, she’d say, “Now Jim, before I give you the cake, do you see that cheat grass growing down there below the wisteria? Get down there and pull that out would you?”

I’d be down on hands and knees and she’d admonish me to “be sure you pull it out by the roots, or else the damn stuff will just grow back.” Thinking my work was done, I’d start to reach for the plate and she’d lead me down the fence a bit farther. “Now look right here….I think that might be a goathead. Get that out of here or we’ll never be rid of those damn stickers.”

Eventually, I’d get my cake. I ate a lot of cake and pulled a lot of weeds over the span of 15 years.

She was also someone whose shoulder I could cry on when the need arose. Once, yet another girlfriend had left me and I was feeling pretty blue. Toots was sympathetic. “Don’t worry Honey, somebody else will come along.” I shook my head and doubted I’d ever smile again. With a twinkle in her eye, Toots smiled and said, “These girls don’t know a good thing when they see it, Jim. And I can tell you this…if I was 30 years younger, you wouldn’t be sleeping over there all by yourself.”

Toots laughed, took another drag from her cigarette and went back inside. It was the story of my life—Timing is everything.

More than anything though, Toots loved to talk about her past and the happy life she’d led with Dick. She could paint an image of Moab that made me long to have been a part of those peaceful times as well. She especially loved those days just before the war began, when she and Dick were poor but happy and free.

By 1940, Toots had set aside her riding jeans for a dress and domesticity. But the real world seemed very far away. It was hard to imagine, standing at the corner of Main and Center Streets that much of the “civilized world” was embroiled in yet another world war. Radio reached Moab, even in the 1930s, and Toots remembered hearing her first broadcast on Bish Taylor’s old Crosley radio. They could hear the news—-Hitler’s Blitzkrieg had crushed most of Europe that spring and in June, the Nazis marched through Paris. Roosevelt was preparing the nation for war, but it all seemed so abstract in this remote red rock outpost.

In 1940, the road to Moab from Crescent Junction was still dirt and gravel and was “still slicker than snot on a glass door knob” when it rained. Plans to improve and pave the highway had been announced in 1939, but the coming war put everything on hold for “the duration.” Nobody went to Moab for the weekend. It took a weekend to get there, even if they only lived in Salt Lake City. Kids rode their bicycles but the bikes only had one gear and coaster brakes and the frames were not made from titanium alloys. They didn’t cost $3000.

As a kid, Toots cut through backyards and orchards to Ollie Reardon’s melons; she would not have seen men and women on the streets wearing skin-tight biking outfits of Lycra or Spandex. Toots was grateful to have anything to wear at all. Usually faded overalls and a cotton shirt were good enough.

Nobody did the Slickrock Trail except for the cattle that roamed the Sand Flats and the occasional rancher who was rounding them up. Nobody did The Daily but a few of Toots’ friends who fell into the Colorado River when they got too close to the eddies that swirled near Moose Park. More fishing poles than can be counted lie in the deep holes near the old stone picnic tables. And nobody did Satan’s Throne except for the ravens that floated effortlessly by it and built nests in its crevices and watched the world below with casual scorn.

Backyard hot tubs with super-turbo-power jets were nowhere to be seen, but by late summer, the potholes in the slickrock above town that still held water could feel very warm. Toots was glad to share the potholes with the thousands of frogs that hatched each summer and sang her to sleep at night.

A fairly decent cup of coffee could be had at the Club 66, but skinny-double-decaf-mocha-lattes were unheard of and unpronounceable anyway—-still are. Beer was available and it might have been home-brewed but it wasn’t micro-brewed. And it was usually served cold but regular power failures drew occasional complaints from Moabites.

Hardly anyone in Moab owned a new car in 1940. The Depression made sure of that. Old cars and trucks limped along, held together with baling wire (Duct tape had not been invented) and horses still provided conveyance for many. Toots depended on her feet to get her just about anywhere her heart desired. Hummers and SUVs and ATVs and ORVs and even Jeep 4WDs were beyond the realm of Toots’ imagination.

Toots’ summer nights were unfettered by credit card debt and staggering mortgage payments or time-share condo schemes. Or late night indigestion from a Big Mac, or a Whopper, or a Soft Taco Supreme, or a Lean Cuisine frozen dinner. Her evenings were spent with Dick, watching the twilight fall over their mining camps at Mollie Hogans or Squaw Park, or in the little hamlet of Moab, listening to the croaking and humming of frogs in Mill Creek or the rustle of a summer breeze through the towering branches of a cottonwood tree and believing that it would be this way forever. Her life was a quiet adventure in the best sense of the word and the experience didn’t cost her a penny extra. She was blissfully ignorant of a future she would live to see, and it would all happen within the span of her remarkable life.

Toots McDougald died on January 26, 2001. She was laid to rest beside the love of her life, Dick Wright, who died a half century before her. For Toots, it was worth the wait.

http://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/advertise/indexnewz.htm

Wonderful article!! Nobody writes like you. I’m so glad you’re “back”.

Glad you’re back by with your wonderful writing, may we all have a Toots to lean on

Great story telling, Jim! Glad to see the Z is still kicking!!

Another excellent story! Glad you’re still printing your work, revised stories, old or new they are all enjoyed and appreciated. Keep it going on your terms!

Great article. I had the good fortune to meet Toots while I was working for The Times-Independent.

Reminds me of an “old timer” in crestone, co before it went bat turds. My uncle lived in crestone and I would visit him a when I was a kid. I would spend my time hiking, hiking and climbing peaks when I got old enough. Toots Holler was a friend of my uncle’s and shared the crap out of me. Her face looked like a dried apple, but once I took the time to get to know her, she was the sweetest gal one could know. She grew up in crestone during the depression and had wisdom and advice I still tap into today.

It’s great to see you back! Take it at your own pace. We can wait. I wanted to comment on the news in your last edition but couldn’t find the words even though I went through a similar situation 20 years ago. Take it slow, heal and enjoy the coming out of the other end of the tunnel. You’ll be stronger and wiser.

Great story! I love your nonfiction character sketches, which plunge me back into an era it’s hard not to idealize. You make me want to go out and find all my neighbors over seventy.

Great piece of writing about Moab history and the people who lived there in the unpaved over pre-adventure capital of the world days. This belongs in the archives of the Moab Historical Society Museum if there is one. If not, I sure hope that Stiles is leaving his papers to one of Utah’s university libraries for posterity. Long live the Zephyr in whatever form it takes!

You’ve been given a gift. Thanks for putting it to such good use.

“what all the previous comments said” — the usual (seemingly) well-researched & flescht-oubt !

What a wonderful recollection and a priceless snippet of history! Grateful for your efforts and happy to start funding them. Be well.

Thouroughly enjoyed reading about Toots McDougald. Thank you!

Nice work Stiles. You keep working hard at it and I trust you will get a long way in your chosen profession!!

Always interested in accounts of species arrivals

I always love your writings. We’ve been going to Moab since the mid 70’s. Love learning more history.

Enjoyed this nostalgic look into a past, simpler way of life. Beautiful memories of an exceptional woman. You were so blessed to have known her and to have her for a neighbor.

Toots was an incredible woman and I enjoyed reading about her life. She seemed to be a friend for life as long as the cheat grass and goatheads were taken care of. Really enjoyed this story.

Great story! When we head out to the desert, I like to imagine the quiet times, even if, for me, that was only the 1980s. No wonder Toots was grateful for the Moab she knew.

Hay Ranger where is the Arch????

Thanks for the info on Toots Mcdougald’s

I have often wondered about the history of our Home and you helped answer my questions.

I knew that the house was built in the 1900’s because when we were remodeling we found that the insulation was old news papers.

Glad you are continuing to publish articles. Would like to send monetary support but am on a fixed income

Great story. Glad to read your very enjoyable writing again. Keep up the good work.

This was a fantastic story, Jim. So glad you did a long one. I lived in Moab briefly in 1959 and then from 1961-1968 (grade school and jr. high). I must have run into Toots a few times. Went to school with Gil McDougald in jr. high, and my dad used to drive a gasoline tanker truck for his dad. Toots’ life is an amazing and delightful tale, and you told it really well.

Such an inviting, interesting story! We had lots of characters in Searchlight and Nelson. Some lived in caves some in old mine shafts, others in houses just like ours. Ours had been a bank during Searchlights heyday but the bank shades were still there! And mentioning the car situation during WWII–Gail’s Grandad, Clyde C. McDaniel (the middle C didn’t stand for anything but he thought it gave a nice ring to his name and most everyone knew him as C. C. He was Las Vegas’s first Chrysler-Plymouth dealer from 1932 to 1950 but in the war years there were no cars. So C. C. took the real estate brokers’ exam and that’s what he did until cars were again being built after the war. After Gail’s Navy service he attended Chrysler Dealers’s Sons School in Detroit. And of course we in Las Vegas were privy to the atomic bombs being tested at the test site. We’d pack up our youngsters and drive out the highway to the Mount Charleston turnoff to watch the huge clouds. If we were at home,, our venetian blinds would tremble. Quite a period of time, and we were all unafraid. So this story of Toots and her family was the birth of it all, sort of. Really interesting story, Jim Thank you.

So glad you got to know my aunt and thank you for pulling for pulling her weeds! I didn’t get to spend a lot of time with her growing up, so it’s nice to hear your stories with her.

Thanks for all you do!