[T]he splendid days when Harry and Dudy and I would live in Glen for six weeks at a time and see NO ONE else are gone forever no matter how far off the beaten track one ventures in this benighted age. How lucky we were, and how greatly I, the only survivor of the trio, to savor and relish the memory of those halcyon days and nights and months in the most beautiful and friendly of all river canyons, when the mighty river, the theme and reason for being of the whole country up there dominated everything and was the self-propelling highway for anyone with gumption enough to embark upon it.

—Dick Sprang

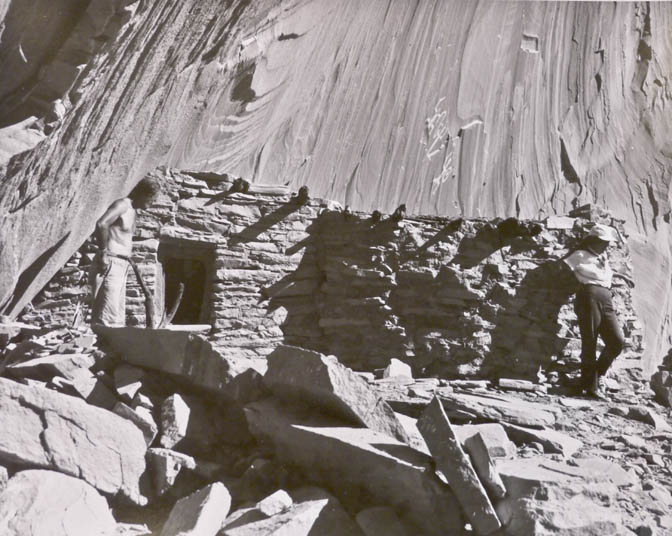

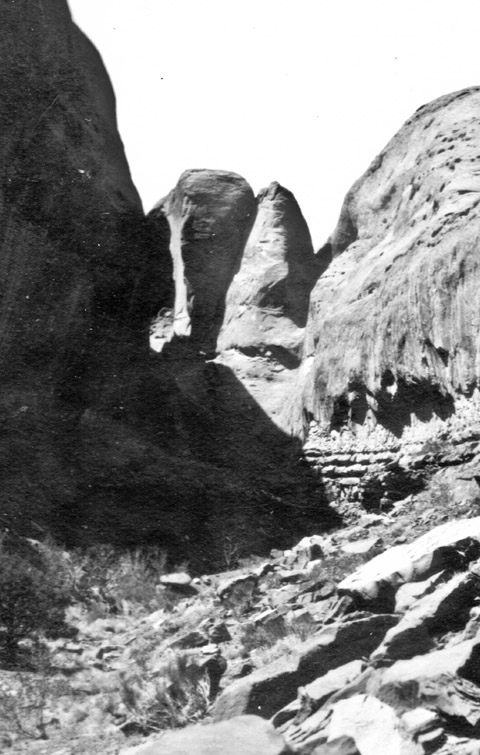

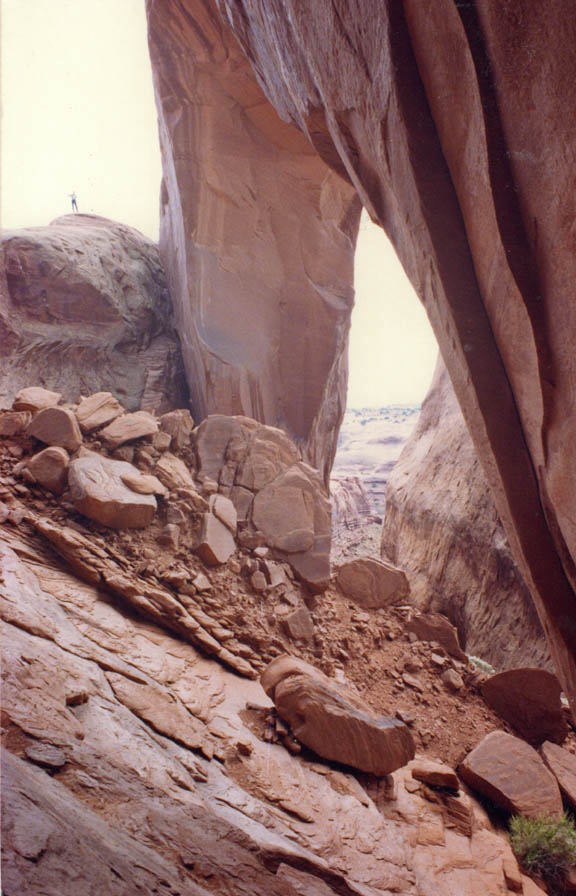

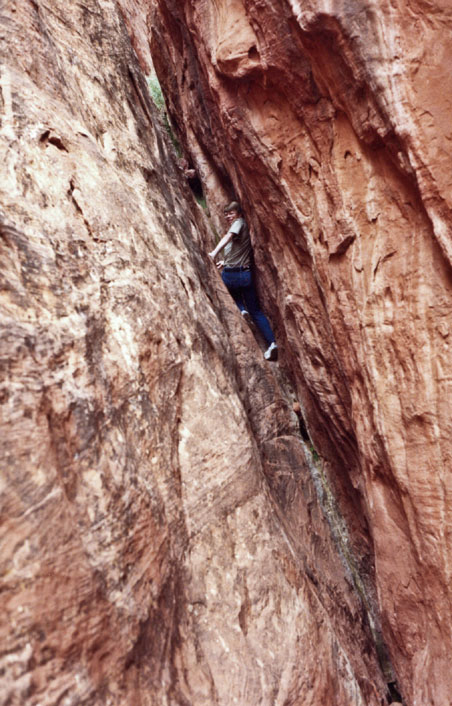

Into the silent cliff dwelling the archaeologists climbed. The year was 1959, and they were engaged in a project to study and document Native American sites in Glen Canyon of the Colorado River prior to its pending inundation by the waters of the Lake Powell reservoir. The dicey route they took to get to the site began at the mouth of Forgotten Canyon—a tributary that, a short distance from the river, necked down to a narrow slot that led early government cartographers to falsely map it as a mere stub of a canyon. To circumnavigate the narrows and its deep pool of cold water, some of the men climbed a steep wall using “Moki steps,” which are pecked indentations in the rock made by someone who had gone that way before. Above the narrows the canyon broadened and continued on for several more miles.

A few miles up-canyon the archaeologists saw the dwelling high in a south-facing alcove. The few rooms, although not large, were remarkably well-preserved. Most of the roofs were intact, and “two perfect red bowls still had scraps of food in them.” Prominently emblazoned high on the cliff wall in white paint were three stylized human figures brandishing what looked like swords and clubs, inspiring the crew chief, Bill Lipe, to name the site Defiance House.

At first appearance, the dwelling had not been visited since its inhabitants had left it centuries earlier. However, the archaeologists soon came to learn that another group of explorers had preceded them there. An outfit, which called itself Canyon Surveys, had made the difficult climb beyond the narrows and first saw the buildings on October 23, 1952.

when they found it in Forgotten Canyon in 1952

Canyon Surveys was the name a trio of Glen Canyon adventurers gave themselves to reflect their passion for discovery and documentation of the outstanding geography, history, prehistory, and scenic wonders of the place. They consisted of Dick Sprang and his wife, Dudy Thomas, of Sedona, Arizona, and veteran river man Harry Aleson of Richfield, Utah. Two four-legged companions accompanied them, as Dick described in his always eloquent way:

Two additional members of our party […] may surprise you: Pard: my splendidly level-headed shepherd dog—in the tradition of Ed Meskin’s dog—and Mickey, Dudy’s supremely tough, gray and white, short-haired tomcat, who was built like a buffalo, had the heart of a lion, and walked the canyons, wading water, with a tiger’s stride, utterly fearless, militant, shrewd, never a problem, always keeping up, and thoroughly at home loving to doze in Anasazi ruins. We called him our Moki Cat. So far as we know, nobody else ever took such an unlikely character down Glen Canyon and up many of its tributaries on four separate trips. If you have wondered if we three were somewhat crazy, your suspicions stand confirmed.

Dick had enlarged the prehistoric steps, and, with the aid of ropes, a harness for Pard, and a fishing creel to hoist Mickey, they all made it into the upper canyon where they spotted the dwelling. Dick was thrilled.

The silence was tangible, a permeation uninterrupted through the centuries. To me, the stillness possessed the hush of reverence. Here a tide of history rested, unaware of all that had transpired on the planet since these people had departed. The high south cliff cast shade on the buildings and glyph wall whose surface was warm against my palm as I wondered if it had been warm to hands of centuries ago. Of course, it had been. Whatever changed in this forgotten canyon? We were aware we were keeping our voices low. We smiled at that. When Harry called his description to Dudy on the canyon floor and broke the spell, we smiled at that, too. Noisy mankind had returned.

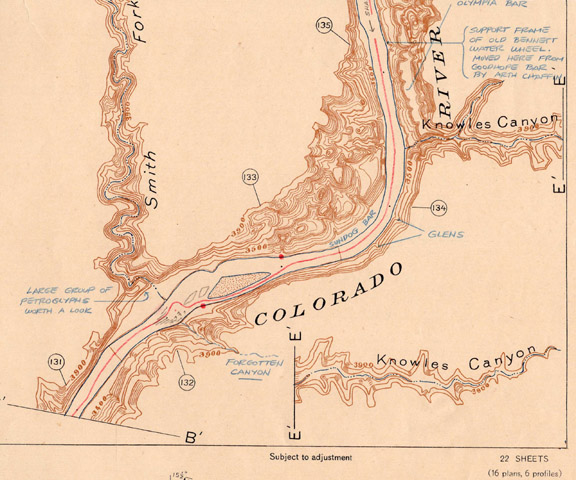

Dick’s fascination with Glen Canyon originated in his meticulous research of its literature before he had ever come into the country. Years earlier, he had acquired, among many books and other documents, a set of the 1921–22 USGS Plan and Profile maps of Glen Canyon, which show the mouth of a “tall and imposing” side canyon that pinches off to nothing about a half mile above its mouth. A few years later, he recognized that the map was in error and determined to discover the real character of the tributary:

I thought nothing of this when I first acquired the 1921 sheets while living in New York City in the early 1940s. But after coming to Arizona in 1946, I purchased from the USSCS the complete 1937 aerial photograph coverage of the Glen Canyon country, and when I undertook a thorough study of it in comparison to the 1921 survey sheets, I discovered that at Mile 132 a canyon of approximately nine miles in length debouched. This sparked interest. Why had not the USGS surveyed this major tributary?

Dick and Dudy first boated through Glen Canyon in 1950 in an oar-powered Navy surplus rubber raft. They became hooked, returning twice in 1951, then again in 1952 and 1955. They typically would spend a leisurely six weeks on the river, allowing ample time to enjoy the scenery, explore, or just relax in camp.

In 1956, the couple moved from Sedona to Torrey, Utah. Dudy passed away in January 1958, and Dick married a local artist, Elizabeth Lewis, later that year. He took his new bride on two Glen Canyon excursions, one of which she beautifully documented in her book, Good-Bye River.

By that time, construction had commenced on Glen Canyon Dam, which would result in the flooding of their beloved canyon. Dick refused to call the stagnant, backed-up water by its official name—Lake Powell—but would only refer to it as “the reservoir.”

Over time, water covered the narrow, lower section of Forgotten Canyon. As it got sufficiently deep, visitors could moor their boats directly below Defiance House and climb an easy trail into the alcove. The Park Service promoted the dwelling as one of the major scenic attractions of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, stabilized it, and provided interpretive information.

After several years of marriage, Dick and Elizabeth divorced. Dick remarried Marion Lyday of Sedona, and the couple bought a house in Prescott, Arizona. At about that time, Harry Aleson passed away. Pard and Mickey were long gone, and only Dick was left to remember the glorious days when the Canyon Surveys team reveled in the delights of Glen Canyon.

Dick’s last visit to Defiance House was in the mid-1990s when he and I rented a power boat at Hall’s Crossing Marina and cruised up to it. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

.

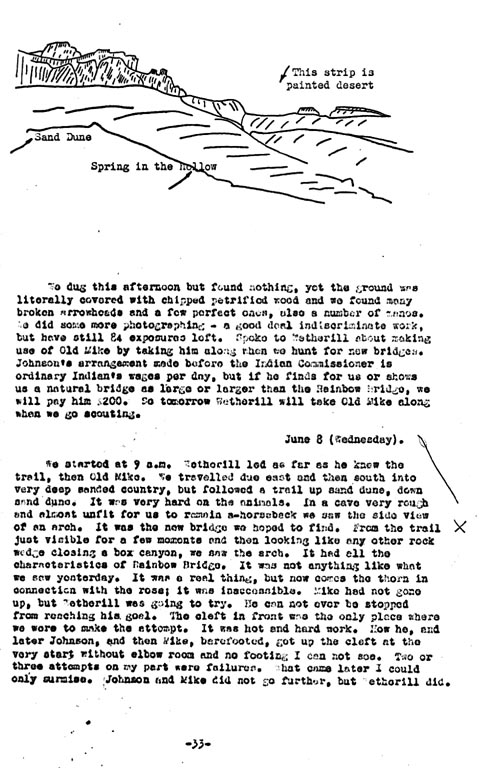

In September 1978, another pioneering Glen Canyon adventurer from Prescott, Dr. Gus Scott, received a letter from Stan Jones of Page, Arizona. Stan was known as Mr. Lake Powell because he had explored the reservoir by power boat as the water was rising; knew its nooks, crannies, and fishing holes better than anyone else; and was the creator and publisher of the popular “Stan Jones’ Boating and Fishing Map” of the lake. At the time of his letter to Gus, Stan was heavily engaged in researching the history of Rainbow Bridge, a spectacular sandstone span across another of Glen Canyon’s many tributaries. Stan attached to his letter a draft account of a January 1931 boat journey to Rainbow Bridge and beyond by my great-grandfather, John Wetherill, and his companion, Pat Flattum. (For more on this journey, see my article, “January 1931: The Strenuous Life” in the August/September 2017 Canyon Country Zephyr.) The two men had motored from Lees Ferry, Arizona, up the Colorado River into Glen Canyon, and Stan suggested that theirs was “the first up-river by boat, ever.” Gus showed the letter and its attachment to his long-time friend, Dick Sprang, who took strong exception to Stan’s assertion.

Dick took it upon himself to write to Stan and correct the record. The manner in which he did so attests to his depth of knowledge, refined manner, and exceptional way with words:

In December, 1899, Robert Brewster Stanton and 11 men employed by the Hoskaninni Company, took four boats from Hite to Lee’s Ferry and did assessment work on the company’s 160 previously staked, contiguous claims that ran the entire length of Glen Canyon. One boat was an 18-foot launch powered by a gasoline inboard engine. At Lee’s Ferry the engine, battery, shaft and screw were removed to be freighted overland to Hall’s Crossing (right bank).

On January 1, 1900, M. J. Ryan and 10 men of the down-river party (Jack Uden, Frank Bennett, John B. Hite, Jerry Johnson, Mat Scarlet, Frank Brown, Albert Riggs, Walter McAllister, Will Emmett & Frank Hayes) departed Lee’s Ferry with the launch, the Little River, and two oak boats, heading up-river to Hall’s Crossing, and later to Stanton Canyon (then called Wilson Canyon), and eventually to the dredge construction site at Camp Stone, Mile 122.85.

The time consumed by this party in navigating up-river between Lee’s Ferry and Hall’s Crossing (119 miles) is not given in any records available to me, but it must have been considerable, what with floe ice probably being on the river, and an extreme low stage of water which would compel a lot of dragging. Sail was used when winds were favorable.

From January 29, 1908 through February 22, Bert Loper dragged, willowed, and rowed his steel boat from Lee’s Ferry to the head of Ticaboo Rapid (Ticaboo No. 2), and later, after visiting Cass, went on to Hite. Bert’s fascinating journal of this trip is reprinted in my old friend Pearl Baker’s biography of Bert, Trail on the Water, Pruett Publishing Co., Boulder, Colorado (available from Pearl at Green River, Utah. This book is required reading for Glen Canyon history).

Dock Marston reports that Bert made a round trip to Lee’s Ferry to study the Spencer mining, December, 1911 to February, 1912. Pearl does not mention this.

In the days of the gold excitement in Glen Canyon, boats could be numbered in the hundreds. There is a report that, in August, 1897, 20 or 30 boats were observed at Lee’s Ferry. There is no question that many prospectors arrived at the river at Lee’s Ferry and made up-river expeditions, and that others put in at Hite, Red Canyon, Hansen Creek, Hall’s Crossing, Warm Creek, and even Hole-in-the-Rock, and went down-river or up, willowing, dragging and rowing. Lew Chaffin, brother of my old friend Arth Chaffin, says that around 1895 over 100 prospectors in the Oak Placer, California Bar, Smith Bar, Moki Bar area petitioned for a post office to be established at the mouth of Hansen Creek […].

As an example of this upstream activity as late as the 1920s in Glen Canyon, my friend Howard Teeples, now dead, of Bicknell, Utah, and Billy Hay, also deceased, took horses and boards and supplies down Hansen Creek in the spring of 1928 to Smith Bar at Hansen’s mouth in Glen. They built a skiff and caulked it with road tar. They used a metal sign to reinforce the transom because they had hoped to borrow an outboard motor. Nobody would loan them one.

With Billy at the oars and Howard (Howd) in the sternsheets, they tried to cross to the directly opposite foot of California Bar (Mile 130.3) with Howd holding the horses which swam behind the boat and kept trying to climb aboard. After a lot of splashing and cussing and ring-around-the-rosy, they made the crossing. At the Mitchell, Seabolt, et al workings on California Bar, they appropriated part of a large metal highway sign that had been brought to the bar by miners for use as a shaker screen. They hammered it into a form that would fit the badly leaking hull of the skiff and sealed the whole works together with more road tar and crimped nails.

They left the horses to graze on the lush bar of those days and took off down the river to enlarge their fortunes trapping beaver. They also washed gravel and wound up at Wright Bar at Mile 24-25 on the right bank one half mile below Navajo Creek. Howd said they had trapped two beaver and washed no color except the usual elusive fines, nothing worth locating. Half starved because they had counted on beaver to augment their supply of grub, and with their beans and baking powder damn near gone, they decided to give up and go home. It was only 24 miles to Lee’s Ferry, but their horses were at California Bar, so they started back up-river—106 miles to go.

“How in hell did you do that?” I asked Howd.

“Willered,” Howd said.

“And what’s that?” I knew but I wanted to hear him tell it.

“Oh, you grab aholt of them little scrub willers and piss brush and pull until you run outa shore, then row like hell acrost to the other bank and grab aholt again, or maybe drag up the middle of the river on them cross-over bars, you know how she is in them wide places.”

“How about when you had sheer wall on one side of a deep, narrow stretch and an opposite bank you couldn’t work?”

“Then we just rowed like hell with I and Billy facing each other, all four hands on the oars. Didn’t make much distance in them places. But mostly it was shore work, linin’ up through rocks, and very seldom just walkin’ nice smooth sand beaches […].”

In October of 1951, long before I heard Howd’s story, I camped on the left bank bar just down from Hole-in-the-Rock, near the foot of the dugway the wagons used climbing out to the Kayenta bench, and, while searching the bar downstream, ran onto a crude metal and wood skiff buried deep in high growing brush. I cleared the brush in order to photograph and measure the boat. It had two sets of driftwood thole pins. There was something familiar about it, and when I got home I checked the photograph opposite Page 184 in Clyde Kluckhohn’s Beyond the Rainbow (The Christopher Publishing House, Boston, 1933). It was the same boat Clyde had used to ferry his party to the right bank in July of 1928 when he took a pack outfit from the bridge to the San Juan, and, using the old Wilson Creek Trail out of the right bank of the San Juan, crossed the divide to Cottonwood Valley (now erroneously called Cottonwood Canyon, which is the name of the canyon now called Reflection) and down it to the river and over to the top of the Kaiparowits.

Stan appreciated Dick’s lengthy commentary, and the two men became good friends.

I don’t know if it was Divine Providence or just luck that led to my friendship with Dick, but it was a most fortunate, life-changing turn of events for me. Over time, I came to realize that it was for Dick, too.

In 1978, I took a job with Pan American World Airways in the Pacific Northwest. Although my duties had nothing to do with airplanes, I did have a fringe benefit of air travel to just about anywhere for very little cost. I made several flights to Boise to visit my aunt, Johni Lou Duncan. One of those excursions, in early 1979, coincided with that of another visitor, Stan Jones, who happened to come to my aunt’s home the same weekend to go through her archive of Wetherill records. Stan and I hit it off despite our age difference—I was 29, and he was 60. But, to quote my great-grandfather, John Wetherill, “As Kipling would say, this is another story.”

Some months later, Stan kindly guided me on an excursion along the long trail my great-grandfather had used to access Rainbow Natural Bridge, giving me my first opportunity to see the incredible countryside and its crowning glory, the spectacular bridge. Knowing of my interest in the history and geography of the Utah/Arizona borderlands region, he recommended that I contact two Prescottonians, Dick and Gus, who would be interested in learning more about my pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills. I called Dick when I got to Prescott, and he immediately and enthusiastically invited me to his house. Soon after that, I met Gus and his wife, Sandra, as well.

On November 24, 1979, my new friends Dick and Marion Sprang graciously hosted my mother, Dorothy Leake, and me at their home for a dinner and story-telling session. As we sat talking, my mother recalled an excursion her grandfather, John Wetherill, had taken her on in 1937 when she was twelve years old. She was visiting “Daddy John” and her grandmother, Louisa (“Mama Lou”), at their home and trading post at Kayenta, Arizona, in the Navajo country when her grandfather asked her to join him and her uncle, Milton Wetherill, on a drive. They were visiting a remote place near Monument Valley on a mission that had something to do with the wealthy New York City businessman and amateur explorer, Charles Bernheimer (for more on Bernheimer, see my article, “The Gentleman Explorer: Charles Bernheimer and his Canyon Country Expeditions,” in the August/September 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr).

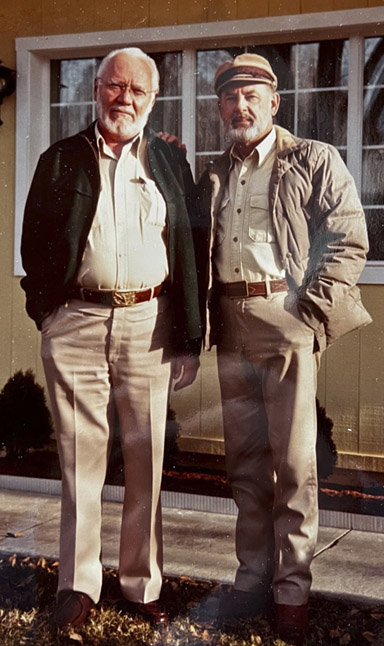

Photo by Gus Scott.

Dick was fascinated by the story and resolved to ascertain exactly where they had gone. Over a period of time, we determined that their destination was Clara Bernheimer Natural Bridge, which Bernheimer first visited in 1927 and named for his wife. But we were unable to locate the arch on a map or learn of anyone who could tell us where it was. (It was common in those days to refer to all rock spans as bridges rather than arches, regardless of whether they crossed watercourses.)

From then on, I visited Dick often. We spent many hours swapping stories, sharing the results of our latest historical research, and discussing countless other topics. If we had recorded our conversations, we would have had enough material for an interesting book. We joked that we should form a business called “Sprang-a-Leake Plumbing and Roofing Repair.”

Both of us took great pleasure in those sessions. “It’s great to know you, Harvey, and to have this kind of stuff to talk about,” Dick wrote me. “What’s more fun?”

During one of our get-togethers, Dick pulled out some aerial photos of the canyon country and his stereoscope. He showed me how to line everything up, and when he directed me to look through the eyepieces, I was stunned! The three-dimensional view and sharp resolution of the photos revealed beautiful details of the terrain that no map could convey. “Like seeing things through the eyes of God,” Dick said. He also walked me through the rather convoluted process of selecting and ordering images from the Government in “stereo pairs.”

From our study of Bernheimer’s notes and photos, we knew that Clara Natural Bridge was at the head of a small gorge somewhere south of Monument Valley. Viewed from the bottom of the draw, only one end of the arch could be seen.

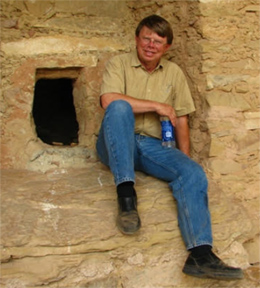

I ordered several aerial photographs of the area, based on my best guess of the location, and studied them in 3-D. In the maze of canyons, I spotted a particular feature that looked like the best candidate for the arch. Dick agreed that this was probably it. To make a long story short, we plotted a route to it, and a party consisting of Dick and Marion Sprang, Gus and Sandra Scott, Gary Topping from the Utah Historical Society, and Martha Austin, Ed Garrison, and their baby, Nanibaa’, from Kayenta went there on April 23, 1983. That was the place! Unfortunately, I was unable to participate in that outing due to work obligations.

We scheduled another expedition, in which I was able to participate, with the goal of climbing up the steep crack at the head of the draw to get under the arch. Since I was a daredevil climber in those days, the others sent me up the defile with a rope.

We were impressed by the size and beauty of the arch. Its span was later measured at 140 feet—the third widest in Arizona.

Dick was overjoyed, not only that we succeeded in fulfilling his goal of rediscovering my mother’s childhood destination, but that I put his training on the use of aerial photographs to good use. “We all enjoyed Harvey’s quiet but obvious satisfaction in having duplicated his great-grandfather’s feat,” Dick wrote, “and after failing to learn the arch’s location from anyone he interviewed, found it himself on an aerial photograph and suggested the best of the two ways to reach it. Harvey is a rare and splendid man.” Although I thought Dick exaggerated my qualities, I was honored by his kind words and pleased that he, too, derived gratification from our relationship.

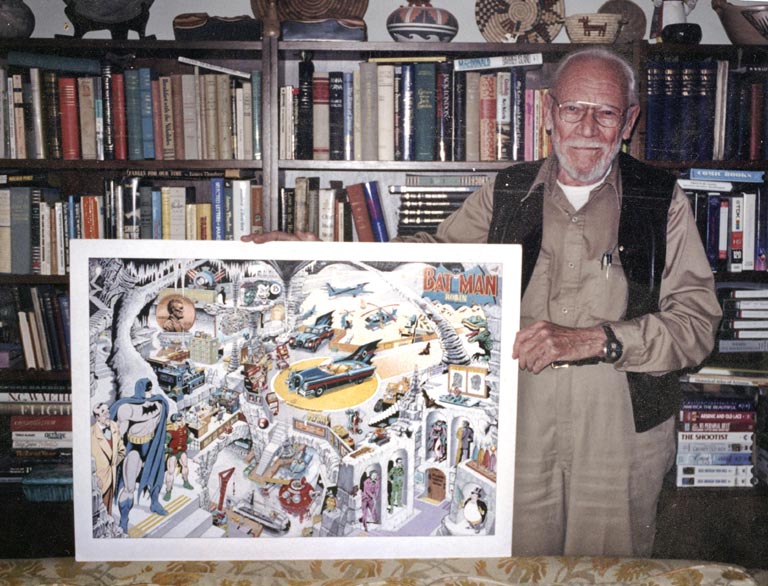

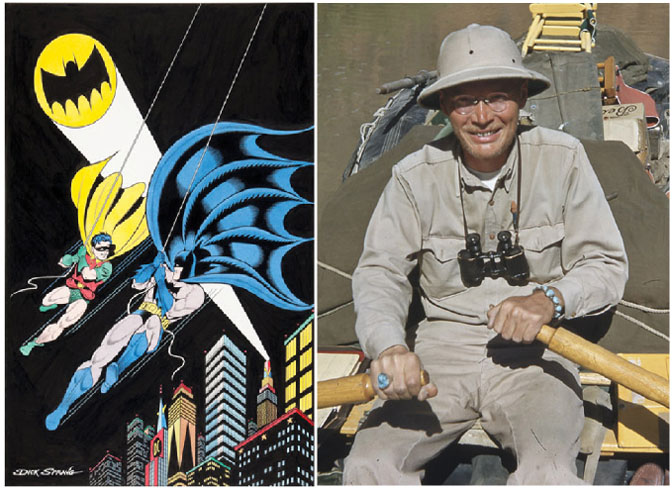

I had known Dick for some time before I learned of a whole different dimension to his life. Gus told me that, in his earlier days, he was a legendary artist of Batman and Superman comic books. I asked Dick about this, and he recounted many amazing stories of his art career that began in his home state of Ohio and landed him in New York City before he moved out West.

Self-taught, Dick had exceptional creative and technical talent that got him a job when he was nineteen years old with the Toledo News-Bee, designing and drawing advertisement and editorial art. Seeking bigger and better opportunities, he moved to New York City where he quickly found employment drawing illustrations for pulp novels. He wrote some of the stories as well. A few years later, seeing the impending demise of the pulp magazine industry, he applied for work with DC Comics, which jumped on the opportunity to add such a talented artist to their team. He created the pencil and/or ink work on stories written by others.

Dick’s fascination with the history and geography of the Southwest compelled him to move to Sedona in 1946, where he could continue his career remotely. After two decades with DC Comics, he resigned in 1963. During his retirement period, he continued to create drawings for his own gratification.

A few years after Dick and I met, he learned that modern-day comic fans had discovered his early-day work. They admired his “clean line and bold sense of design,” and considered him “the supreme stylist” of the early Batman artists. He hired an agent, Ike Wilson, who arranged for him to be featured at comic conventions, and they developed a clientele for his re-creations of old Batman comic book covers. He also created a few new, conceptual pieces that they marketed as limited-edition posters.

Despite the newly gained recognition of his artistic expertise, Dick’s heart was still centered on the Glen Canyon area. In about 1983, he resumed making pilgrimages there. No longer interested in sleeping on the ground or hiking long distances, he would rent a mobile home at Hall’s Crossing Marina and go out on the desert in a four-wheel drive vehicle to revisit his old haunts. His favorite place was the beautiful Lake Canyon that he and Harry Aleson had first explored in 1952. Getting back to that country was more important to Dick than all the glory from the art community:

My primary interest in life is the canyon country of Northern Arizona and Southern Utah. And, a secondary interest in the San Juan mountains of Colorado. And a tertiary interest in Batman and Robin. They make my living. Only my special friends share the wonderful adventures we have up there. The sense of country, solitude, and how to live and exist in that sort of environment. […] We understand the disease and addiction of the canyon country, the thousands of square miles of it. You talk about addiction! Wait till you fall in love with the slickrock country. You’re hooked forever. There’s no cure.

Dick gave me a standing invitation to join him on what became his annual “Halls in the Fall” outings. Most often, we would spend our days driving in my 4Runner, following any two-track road we could find, just to see what was out there. “The window rolled down, and you’re in four-wheel drive,” Dick explained. “You just cruise at three miles an hour and watch the country slowly move by, sand and bushes in between. With scattered juniper and pinyon trees, and down in the canyons beautiful tapestry walls and big oak trees, cottonwood trees and water and grass. And aborigine Indians sites, Anasazi. Beautiful petroglyphs on the walls. I’d go into some canyons very few people have ever been in. I don’t tell where they are. It’s just wonderful.” We spent our evenings in the mobile home, where we never had a shortage of subjects to talk about.

Despite his aversion for “the reservoir,” Dick sometimes rented a power boat to get him to other memorable places. That was the situation when he boated me up to Defiance House. I sensed that, in addition to seeing it again for himself, he wanted to somehow pass on some of his legacy to me. We continued up-canyon to Tapestry Wall, and he described how much more dramatic it was in the river days before its bottom portion was under water. He told me of a route we could take to drive to the top of it. We will go there on our next outing, he said. “Great times,” he declared. “Let’s hope the years give us many more of them. They will for you young guys, not so many more for an old crock like me. But I’ve had a hundred times more than my share when I was lusty and strong and did the whole bit. Today, as fat as a third base coach, I do the driving and make cracks. It’s a great life if you know when to weaken.”

Both Dick and Marion were quickly declining in health. We failed to make it back to the canyon country the next year, or ever again. On Valentine’s Day of 2000, Dick was moved into a care home where Marion was already staying. “Don’t ever stop coming to see Dick,” she admonished me. That gave me the feeling that our visits were as important to him as they were to me.

On May 10, Gus, Sandra, and I were in Moab when we got word that Dick had died. His passing was a sad ending to a remarkable period of my life, but I was still blessed with the irreplaceable memories, knowledge, and wisdom he had bestowed on me. “It seems that explorers are always learning something or another. Their education never stops. Dick Sprang was such an explorer. He had the ability to believe in himself beyond normal limits,” eulogized Dick’s friend and biographer, Bob Koppany (His book is The Art of Richard W. Sprang…).

Gus and I had the onerous task of clearing out Dick’s possessions from his house. It was like a treasure hunt to uncover his large accumulation of belongings—many of them fascinating. But the most touching thing I found, on his nightstand right beside his bed, was a stack of old birthday cards I had given him through the years. Who would have known that they would have had an enduring meaning to him?

Dick Sprang was one of several remarkable elders I have been privileged to know. Stan Jones and Gus Scott were two others. A few years after Dick’s passing, I read a manuscript that my great-grandmother, Louisa Wade Wetherill, had written. It was an oral history of an elder that she got to know in the early 1900s—a Navajo man named Wolfkiller. He related to her his amazing legacy that had been passed down to him by his own elders—his grandfather and mother—as they taught him to follow “the path of light.” It occurred to me that the propensity to develop friendships with older people, to listen to and learn from their stories, to honor them with respect, and to recognize the great rewards of such relationships, began many years before I was born.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

Click HERE for more Zephyr articles by Harvey Leake.

The Canyon Country Zephyr has (with one 45 day interruption)

posted continuously since 1989.

What a story! Just fascinating! Dock Marston was the only familiar name to me and yet i could feel the passion and need to find that arch, and then to continue “until death do us part” that these adventurers had, wandering through that beautiful Canyon country as often as they could! I feel as if I’ve been on an adventure having been privy to this tale!

I live in AZ and in thrift stores am constantly finding small press and self-published books from the 50s-70s about the desert and the canyons and the mining towns. I am always disappointed to thumb through and not find anything written or drawn by Dick. It’s hard to believe that a man who made his living in the arts for 25 years just completely stopped doing artwork from 1963 until the 1980s recreations started.

Always REALLY enjoy Harvey Leake’s articles and particularly this one. Dick’s paragraph about his life interests resonates powerfully with me. “You’re hooked forever. There’s no cure.” Indeed. (And Harvey’s even got a ’92 4runner!)

E P I C synopsis/ses. i’d ‘pert near assume everyone who wanders the Zephyr’s hallwaze & passages readily identifies with explorations such as these ~

Very interesting history of the amazing early and current explorers and historians of the Glen Canyon of which Harvey is one!!! Their love of the canyon is apparent in this article, and it inspires others to visit and preserve this very special canyon!! Enjoyed this article very much. Thanks

Wonderful and poignant story that captures the special people and landscape Harvey knows. Thank you!

This is a fascinating, if lengthy, letter written by Sprang to Stan Jones in 1982 in response to Jones’ questions about the roads in the Hite area before it was flooded.

These scans are from the NAU Colorado Plateau Digital Collection and I’ll post the links:

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51545/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51546/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51547/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51548/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51549/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51550/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51551/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51552/rec/28

https://cdm16748.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/cpa/id/51553/rec/28