For the last two decades, the American Southwest has been caught in the grip of the worst drought in 1200 years. At the same time, the human population of this region, an area that was already a desert before the rains stopped coming, has exploded. Consequently, the Colorado River, the lifeblood of the Southwest, is now seeing its annual flows decline dramatically and its two major reservoirs, Lake Mead, behind Hoover Dam and Lake Powell that was created by Glen Canyon Dam, are at historic lows. Emergency plans to deal with the crisis have already been implemented. It means drawing down from other reservoirs further upstream to raise the levels of Powell reservoir. At Glen Canyon Dam, the water level is within 30 feet of dropping below the level of the water intakes, they run the generators that create power for millions of Americans

Assistant Interior Department secretary, Tanya Trujillo fears that Powell could decline even more, to a “critically-low” level in the next two years. If that were to occur, the dam could no longer generate hydropower. Trujillo said, “That would create a number of problems for the water and electricity supply and for the dam itself.

The low water levels are exposing some surprises as dry land emerges from the reservoirs. Last week, boaters near the Boulder City marina spotted a rusted out 55 gallon barrel, stuck in mud and exposed for the first time to fresh air in decades. When a woman got closer, she realized the contents of the barrel were the decayed remains of a man, who had apparently been shot to death in the late-70s. The poor victim was then stuffed in the barrel, weighted down, and dumped into the lake. It was assumed he was out of sight forever. Law enforcement authorities have indicated that the man died of a gunshot wound to the head. The late 70s and early 80s were still gravy days for the Mafia and it’s expected that many more barrels are out there to be found.

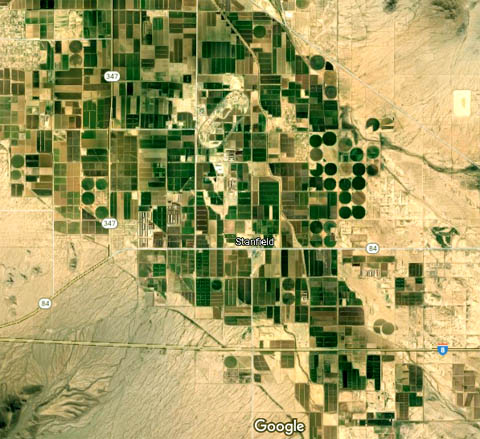

Other surprises await all of us. The biggest shock may be years or decades ahead when the overpopulated American Southwest suddenly finds itself bone dry. And yet, while agriculture in Arizona for example is already facing massive cutbacks and devastating crop losses, residential development in southern Arizona continues at a record pace. In April CNBC reported that:

“While there is a shortage of water, there is also a shortage of housing. The U.S. currently needs over a million more homes just to meet the current demand, according to an estimate by the National Association of Home Builders. Other estimates are even higher. As the millennial generation hits its prime homebuying years and Gen Z enters the fray, the supply of homes for sale is at a record low. Builders are hampered by high costs for land, labor and materials, so they are focused on the West and areas like the suburbs of Phoenix, which are growing rapidly.

“On a vast swath of land in Buckeye, Arizona, just west of Phoenix, the Howard Hughes Corporation is developing one of the largest master-planned communities in the nation, Douglas Ranch, flooding the desert with housing.”

Their web site markets their plan to build 100,000 homes on 37,000 acres of land, for 300,000 potential residents. And to be sure the corporation provides the necessary amenities, the plan includes 55 million square feet of commercial space as well.

The developer says, “water will not be a problem.”

And in the short-term, he may be right. It’s becoming increasingly clear that as the Southwest dries up, and those with vested interests scrutinize what they believe is the “highest and best use” of this precious resource, farmers are going to pay the ultimate price—most likely to the point of extinction. (This very scenario was discussed at great length in my 2007 book, “Brave New West.”) In fact, farmers are already going extinct. A recent CNBC report described in painful detail just how badly the agricultural industry is being hit. In part , CNBC wrote:

“It’s heart wrenching,” said Caywood, a third-generation farmer who manages 247 acres of property an hour outside of Phoenix. “My mom and dad toiled the land for so many years, and now we might have to give it up.”

Farming in the desert has always been a challenge for Arizona’s farmers, who grow water-intensive crops like cotton, alfalfa and corn for cows. But this year is different. An intensifying drought and declining reservoir levels across the Western U.S. prompted the first-ever cuts to their water supply from the Colorado River.

The canals that would normally bring water from an eastern Arizona reservoir to Caywood’s family farm have mostly dried up. The farm will soon be operating at less than half of its usual production. And Caywood is grappling with a recent 33% price hike for water she’s not receiving.

“We’re not making one dime off this farm right now,” Caywood said. “But we’re trying to hang on because this is what we love.”

More than 40 million people in the West rely on the Colorado River, which flows along Arizona’s western edge. The farmers hit the hardest this year are in Pinal County, a rural stretch of land where agriculture is receding and slowly getting replaced by solar panels and housing developments.

Water experts scramble for new solutions or alternatives. The goal is always to reduce water consumption, but only so that there is more water for continued explosive residential and commercial development. Doing what is environmentally responsible is never a component in these water calculations and schemes.

And so as we approach the end of the first half of 2022, relevant government agencies and the media continue to report the dire water situation in the Southwest, acknowledge the lack of viable options to increase water supply, and continue to report that demand for it continues to grow, even as conservation efforts are initiated or expanded.

Few saw this coming, even now, few seem to take these dire predictions seriously. One has to wonder what the government was thinking 75 years ago when they thought a vibrant economy with a densely populated cities throughout the most arid region in North America could possibly be a good idea.

And yet, incredibly it could have been so much worse.

WWII and the Post-War Boom

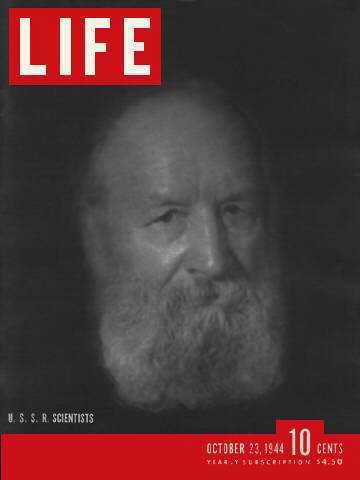

In the fall of 1944, Americans and our Allies were finally moving forward toward victory against the Germans and the Japanese. Much bloodshed was still to come, but there was finally a light at the end of the tunnel. In 1929, the world’s economy had been plunged into a deep economic hole—the Great Depression as it came to be known. Hardships that none of us could comprehend today were endured across the planet. Here in America, poverty and the lack of jobs made the lives of millions unbearable. Poverty was common. It was, oddly enough, only the threat of war and its ultimate arrival that helped reignite the economy, via its demand for a fully equipped military, that put Americans back to work and ended the Depression. After 15 years of hardship, Americans in late 1944 were excited to feel optimistic again. In fact, many Americans were downright euphoric. We had done more to defeat the Axis nations than any other country and there was especially an emphasis on what technology and a booming industrial-based economy could do for the welfare of the country and its citizens. Many Amricans thought there was nothing we couldn’t do, that we couldn’t succeed at. Many Americans set out to prove it.

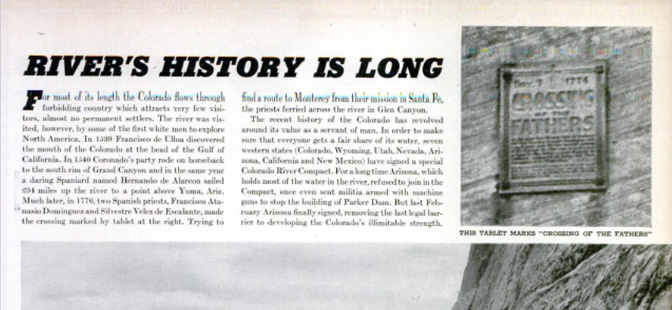

The October 23, 1944 issue of LIFE Magazine made that very point. Though the war’s end was still almost a year away, the US Bureau of Reclamation was already looking ahead to the post-war years and what everyone expected to be a massive economic boom. The article was called, “THE COLORADO RIVER: A Wild & Beautiful River is Put to Work for Man.” While the story was full of spectacular images of the river and the course it took to the sea, and though it noted the incredible beauty of the many and varied canyons, the emphasis was on taming that wild river and making it “the servant of man.” The story explained that once the war was over, the Bureau had very ambitious plans to build a series of dams throughout the West, for the storage of water, for irrigation and for the generation of electricity. They thought they were Futurists, anticipating the needs and wants of the years and decades ahead. Real dreamers.

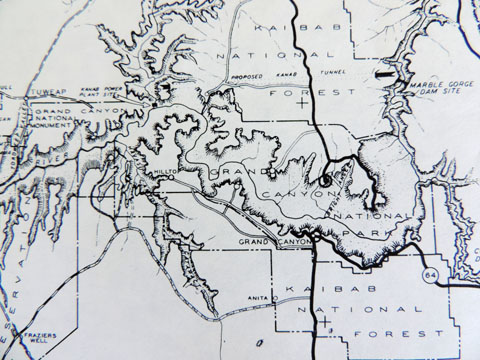

By war’s end, plans for dams were moving full-speed ahead. As noted, the Colorado River flows through some of the most spectacular scenery on Earth, including the Grand Canyon and many scenic areas upstream. The National Park Service was approached and asked to prepare a study of the impacts, both pro and con, that the agency believed would result from the construction of these dams. In 1946, a document called “A Survey of the Recreational Resources of the Colorado River Basin” was released by the NPS. The information and proposals that were presented in that document were mind boggling. What Bu Rec did to the Colorado River, via the construction of dams, pales beside its long term goals.

What Might Have Been

The NPS survey is breathtaking in its scope and in its vision for the future of the river and the Colorado Plateau; with one exception, the NPS response to the Bureau of Reclamation’s plans were quite benign, even supportive at times. The best way to describe the potential impact of these projects is to simply tell you what they had in mind. It’s impossible to include all the proposed water projects. But let’s start in familiar territory and head downstream, over 400 miles, toward Hoover Dam.

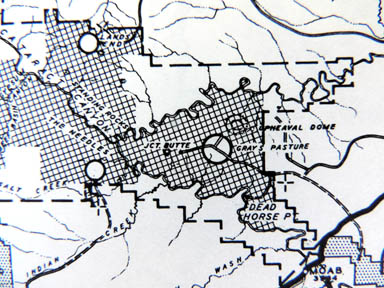

Dam #1: DEWEY RESERVOIR

According to the survey the “tentative dam site is about 30 miles upstream from Moab, Utah…the purpose of the dam is the development of hydroelectric power. Preliminary studies by the Bureau of Reclamation indicate a water surface of about 66,000 acres at full reservoir.” The NPS estimated that the reservoir would extend about 40 miles upstream from the dam, which would have been constructed very near the Dewey Bridge. “In the vicinity of the Big Hole portion of Westwater Canyon, the reservoir at high water would be about 200 feet deep …. Nevertheless the Park Service stated that the canyon “would still retain some of its scenic value.”

There had been a discussion within BuRec of building the dam just upstream from the US 191 bridge at Moab. But it would have flooded State Hwy 128 for its entire length. That option was discarded

Dam #2: DARK CANYON RESERVOIR

Over a hundred miles downstream from Moab and four miles upstream from the mouth of Dark Canyon as it flows into the Colorado, another dam was planned. Its remoteness was a problem—no roads came near it— but that was always more a challenge for BuRec than an impediment. The Dark Canyon dam would have flooded Cataract Canyon and as the NPS noted, “The potential dams and reservoirs would eliminate the thrills of boating down the untamed rivers. The deadly rapids at Cataract, responsible for the tragic ending of several canyon voyages..would be gone. But the Glen Canyon Reservoir would provide access to the wonders of the canyons.”

Dam #3: GLEN CANYON RESERVOIR

Two options were considered for the third major dam at Glen Canyon. One site, just four miles upstream from Lee’s Ferry, was considered. Another possibility was another 12 miles upstream. What was built at Glen Canyon depended on the Bureau’s ability to secure support and funding for three projects that were, in many ways, more grandiose than Glen Canyon,

If the Marble Canyon/Bridge Canyon plan could be approved, BuRec planned to consider a lower dam at Glen Canyon. “A dam 414 feet high would create a reservoir which at normal water surface elevation of 3528 feet would have a surface area of 65,000 acres and a capacity of 8,600,000 acre feet. (Ultimately Glen Canyon dam would become the high dam on the upper Colorado with a capacity at its completion of 27 million acre feet.

Dam #4: MARBLE CANYON RESERVOIR

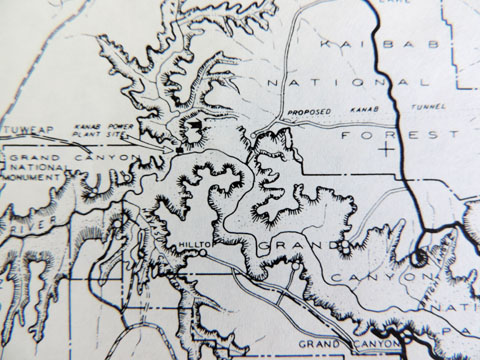

The plan at Marble Canyon is astonishing in its ambition. (You may have to read this twice to understand its full implications.) The Bureau of Reclamation calculated that the vertical fall of the river from the first Glen Canyon dam site to “the headwaters of the potential Bridge Canyon reservoir was about 1,260 feet. That kind of water movement is perfect for the generation of hydroelectric power. To avoid building even more dams within the boundaries of Grand Canyon National park, BuRec offered the “Kanab Tunnel option.”

“To take advantage of this drop and yet avoid the construction of dams or other works in the park, the Bureau of Reclamation suggests a plan to divert waters ‘not needed to maintain a steady stream for scenic purposes in the park’ through a 44.8 mile tunnel from just above the east end of the park to a power plant on the Colorado River near the mouth of Kanab Creek. The capacity of the Kanab Tunnel would be 13,000 second feet. A 298 foot dam at the Marble Gorge site would divert water to the tunnel. Water released from the dam for scenic purposes in the park would pass through the power plant.”

“Scenic purposes?” The idea was to allow just enough water down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon for it to still at least look like a river.

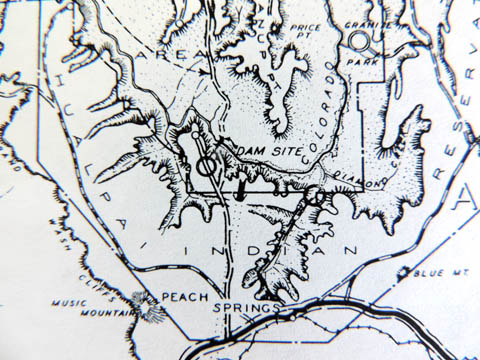

Dam #5: BRIDGE CANYON RESERVOIR

This would be the grandest dam of them all, cruising 740 feet above bedrock; it would “raise the water 672 feet to a maximum of 1,876 feet above sea level…the multicolored canyon walls would tower more than 4000 feet above the fiord-like lake.” The survey again noted that the purpose of the dam was “primarily for the generation of power.” The diverted river would flow through the 45 mile tunnel from Marble Canyon, gaining speed and energy as the water fell more than a thousand feet in elevation.

OTHER SECONDARY DAMS

The number of secondary dams and reservoirs for tributaries of the Colorado are simply numerous to list here. But it should be noted that dams just downstream from Bluff, Utah and another at the Goosenecks of the San Juan River would have altered the landscape of southeast Utah’s rivers even more. Another dam was planned for the Little Colorado River

THE PARK SERVICE RESPONDS

In most cases, the national park Service response to the BuRec plans was tepid at best. It was like a person who meant well, “trying to find the good in everybody.” It was quic to mention the loss of white water rafting along many parts of the river, but as was so often the case in those days, accessibility was a key part of the NPS strategy, as it sought to “provide for the enjoyment of the American People.” And they apparently meant— as many visitors as they could fit through the door by their philosophy toward tourism at the time.

But the NPS took a hard stand when it came to the Bureau’s dam plans for the Grand Canyon. The NPS insisted that:

“…the projects proposed for the control and use of the Colorado River would completely change the natural conditions and character of the river through Grand Canyon National Park where it would be diverted under the plateau through which it has for millions of years been grinding its own way. The river through the Grand Canyon without its grinding against would no longer be the Colorado known to thousands of visitors who go to the bottom of the canyon each season. It would be a clear stream..”

Finally the Park Service summarize that “the Kanab Creek diversion proposal would, in effect, tackle away from the GrandCanyon the very agent that created it; the remaining trickle would be sham and mockery in comparison to the once great force that carved the canyon–the Colorado River..without the normal flow of the river, the significance and completeness of the park will be destroyed and the will of the people defeated.”

(Though the Kanab Tunnel was never built, the high dam at Glen Canyon served to catch the sediments headed downstream and began to accumulate behind the dam from the moment the diversion gates were closed in 1963. Indeed, the Colorado through the Grand Canyon is “a clear stream.”)

OTHER PLANS…ROAD & LODGE FEVER

To provide access to these dam projects, and most of them were in extremely remote and isolated parts of southeast Utah, it would also require the construction of hundreds of miles of new road. Long term, the Park Service believed these roads would create a much more complete transportation tourist infrastructure, and could dramatically boost visitation in the decades to come. The Bridge Canyon site was especially isolated but engineers could already identify several possible routes to the site from US 66 near Peach Springs, Arizona. Once that section of the road was completed, it seemed only logical to bridge the river and extend the highway north, ultimately to carry visitors to Kanab, Zion and Bryce Canyon National Parks.

At the Glen Canyon dam site, which was ultimately completed, a new road was also required to the site, from US 89. A steel span bridge connected both sides of the river, just downstream from the dam, and eventually a new road was built to Kanab, 65 miles west. The newly incorporated town of Page, Arizona was constructed from whole cloth and named for a former commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation. Manson Mesa was a place where the Navajo grazed sheep until BuRec acquired the land and proceeded to build its own city. If you’ve been to Page lately, you’ll know that if their plan was to create a population center where a Wal-Mart overlooks the dam, then they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

The NPS also suggested “major development areas” near many more of the scenic locations on the Colorado River Basin. Plans for commercial park villages, complete with lodges, restaurants, gas stations and curio shops were all considered for Gray’s Pasture on the Island-in-the-Sky, which in 1964 would become part of CanyonLands National Park. Paved roads and lodges were also planned to Rainbow Bridge, Elk Ridge, Hite, Hole in the Rock, the Needles, Lee’s Ferry, and even Lands End. All were regarded as prime development sites.

Again, while the NPS noted that the Colorado River dams into a cold stream would drop the water temperatures dramatically, stop the flow of silt, and alter dramatically the biology of the river, there was always a bright side to the scenarios. The report noted that, “reservoir construction on desert streams can be great benefit to recreation when, as in the case of Lake Mead, it substitutes a large, clear lake suitable for warm-water game fish, together with a second Transition Zone trout stream, for the previously turbulent, silt-laden and unproductive river waters.”

The NPS also wrote that, “convenience of access is an important factor in determining the value of an area for recreational use…high standard roads are likely to receive much larger use…”

In addition to the cross canyon road from Peach Springs to Bridge Canyon dam that would ultimately link with US 89 in Utah, the Park Service proposed to improve the road to Toroweap, a remote NPS outpost at the far west end of the canyon.

“It has been suggested that a loop road…extend down Toroweap Valley around the south end of the Pine Mountains into Whitmore Wash….the best location for a lodge would appear to be at the upper end of Whitmore Wash near Big Spring Wash.” Ranger Riffeey would not have been amused.

The Park Service also recommended a series of air fields to accommodate even more tourists to the various parts of the Grand Canyon and Canyonlands.

Below Hoover Dam, which was constructed in the early 1930s, three other dams —Parker, Davis and Imperial —had also been completed and millions of gallons of water were already being diverted to Los Angeles by the end of WWII. Had these other projects been completed, barely a mile of free flowing Colorado River, from the Colorado state line all the way to the Gulf of California would have survived.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

For those of you who don’t know the history of dam building on the Colorado River, neither the Dewey Dam, the Dark Canyon Dam, nor the Marble Gorge and Bridge Canyon Dams were ever built. The 45 mile Kanab Diversion Tunnel was never bored. Because the Marble Gorge plan was dropped, the higher 710 foot Glen Canyon dam was mainly constructed to store water, so that Upper Basin states of the Colorado River Compact could meet their annual water commitments to the Lower Basin states. But it has also generated hydro-electric power for the cities of the Southwest for almost 70 years. Projects like this allowed the cities of the arid American West to grow in places where this kind of growth made no sense whatsoever. But in the post-WWII era, the optimistic notion that there was nothing American Technology and will power couldn’t do, was almost universal. Environmental and long term economic consequences were not even on the radar.

Now, in 2022, without all those additional dams and reservoirs, the current extreme drought and its effect on the river is already causing river managers and scientists and politicians and engineers to wonder just what we can expect in the future. Had all these structures been put in place 60 years ago, it’s impossible to imagine how much worse the state of water management would be in 2022, or what the Colorado River would look like right now. But it would make today’s crisis look like a cake-walk.

***

In 1950, four years after the Park Service’s survey of the “recreational resources of the Colorado River Basin” was published, with its ambitious plans for the future, the American Southwest was a very empty place. A blank space on the map. Even then, the first rumblings of the post-war boom were being felt across the country and speculation about Americans migrating West became a popular topic of discussion. It was noted, even 70 years ago, that the arid Southwest with its paucity of water supplies should be viewed cautiously when future human development was considered by demographers. Scientists and engineers and practically anyone with common sense could see that places like Phoenix and Tucson and Las Vegas would not be able to handle the kind of rapid growth that was being predicted. But other engineers and developers believed that technology could reduce the potential for disaster—- this is why the Bureau of Reclamation was so ebullient for the dams.

But consider some numbers — historical numbers — not computer models of what might happen. When America conducted its 1950 census, it found that Phoenix was the largest of the Southwest cities at the time –– it had a population of 107,000. Down the road in Tucson, the little town could only muster 55,000 residents that year. And further west, just miles from Hoover Dam, Las Vegas, Nevada’s population was 24, 624.

And in 2022?

Phoenix: 4,584,000

Tucson: 1,003,000

Las Vegas: 2,272,000

And they keep coming. The warnings about water shortages became much more dire, even desperate, in the last 25 years. Confronted with the worst drought in a thousand years, and the possibility that climate change was pushing the crisis even further, more costly proposals like the Central Arizona Project (CAP) sought to seek more ways to utilize the water while never acknowledging their limitations. Delaying tactics. Growth and the development of the Southwest was lauded and applauded. . The people kept coming.

The 2010 census provided some stunning numbers. While the nation’s population had only grown by 10% in the last decade, in the arid American Southwest, the numbers were striking:

Utah: 23.8% growth to 2,783,885 from 2,333,169 in 2000

Arizona: 24.6% growth to 6,392,817 from 5,130,632 in 2000.

Nevada: 35.1% growth to 2,700,551 from 1,998,257 in 2000.

New Mexico: 13.2 % growth to 2,059,179 from 1,819,045 in 2000.

Colorado: 16.9% growth to 5,029,196 from 4,381,281 in 2000

In Utah for example, the population almost doubled since I first moved to Utah in the late 70s. Water managers and politicians and entrepreneurs wondered what was next. It turned out to be more of the same. The 2020 Census revealed that Utah’s population grew by yet another 18% between 2020 and 2020 —the fastest in the nation. Arizona expanded its population by another 12%. Colorado by 15%. Idaho made the Top 10 list for the first time, seeing that state grow by 17%.

More than a decade ago, Richard Seager of Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, noted in an Associated Press interview, “The bottom line message for the average person and also for the states and federal government is that they’d better start planning for a Southwest region in which the water resources are increasingly stretched.”

Seager and his associates, who prepared their report for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007 believe that the drought could continue for the next century and beyond.

Other reports reached the same conclusions. At the University of Arizona, climatologists reported that “both projections and observations indicate residents of the arid Southwest can count on more extremes in years to come.”

Those warnings were issued more than a decade ago, Still Americans keep making the exodus West, in unfathomable numbers. Peter Gleick, the president of the Pacific Institute, has studied water resources around the world. In the arid U.S. Southwest, he noted that recognizing and even conceding the problems of drought, coupled with a booming and consumptive population, has done little to create solutions. “Psychologically and socially,” he explained, “it is hard for millions of people who love this region to admit that it is fundamentally dry and that the rules for building, living, and working there must be different from those in the wet regions where most of these same people were born and raised.”

In 2011, Thomas Whitham, director of the Merriam-Powell Center for Environmental Research at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, warned, “If (Flagstaff) continues to draw down water to maintain our lifestyle with its exorbitant use of water, we can effectively turn a hundred-year drought into a millennium-level drought, which far worsens the community and ecosystem consequences.”

Flagstaff’s population doubled in 20 years to 60,000 in 2010. By 2020 it had added another 20,000 residents. Its metropolitan area, Coconino County and adjacent communities had grown to 116,640 by 2000, a 44 percent increase from 1980 and rose to 142,000 by 2020. The growth continues to place an even greater demand on resources that continue to dwindle.

The story is the same across the West. A Brookings Institution report claims that by 2030, nearly 45 percent of homes in the West will have been built since the Millennium, or almost half the homes across the West in 30 years. Almost half.

***

I learn a lot about my fellow citizens reading facebook entries, sometimes by people I don’t even know. On some facebook pages that carry a special western theme, the interest from people who live in what Abbey called “The Great Siberian East” is almost obsessive—they are in love with the idea of “being Westerners,” even if the reality fails to fit the dream.

One former Arizonan who wanted to move back to Flagstaff from somewhere on the other side of the Alleghenies made his first trip there in a few decades. He was shocked. “Don’t recognize the damn place anymore…It’s as crowded with traffic as Durango. Scratch two more towns off my list.”

But New Flagstaffians came to its defense. “You just need to know where to go,” observed one, “because a lot of places here are still the same. Personally I avoid the east side of town like the plague–it’s like a different city Our downtown is thriving and vibrant,”

Another commented, “Get the mussel dish at the brewery….very good.”

All of these Urban Migrants wanted to be a part of something that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s an interesting irony that almost all “New Westerners” rail against the “redneck” mentality that used to govern the rural west before we came along to save it. But at the same time, they long for the West the way it was 40 years ago.

New Westerners came to live here as permanent tourists. They came to be closer to the beauty they have admired for so long and to rail against those who extract natural resources from it. Many New Westerners consider themselves the True and Just Protectors of the land. But at the same time, they have no problem consuming those resources. They oppose oil/gas production but heat their new homes and power their hybrid SUVs. They condemn timber extraction but build new 4000 square foot homes in the desert and forests of the West.

They condemn the massive dam building projects of the 1950s but only exist in their new amenities-driven environment because the dams that were built made it possible. But they xeriscape their lawns and think they are good conservationists. As the West becomes less of what it was, what really made the difference?

As we’ve noted before in this publication, “It’s the numbers, stupid.” Many New Westerners came here to save it and subsequently ruined it with their sheer numbers and the desire to bring their urban habits with them. I doubt you could get a mussel shell dish in Flag 40 years ago, but who’d be willing to trade a seafood dish for some real peace and quiet? In today’s rush to be part of a myth, I’m not sure anybody notices.

The massive postwar plans for the Colorado River and the scores of water projects that were so enthusiastically embraced, shows just how little we understand this place and how pitiful we are at predicting the future. So many of those BuRec projects were never built. But they got what they wanted anyway. In fact, they got WAY more than they bargained for.

“They that sow the wind, shall reap the whirlwind.”

Jim Stiles is publisher of The Zephyr

PLEASE SHARE…( and THANKS)

I’m grateful to say that rumors of the Zephyr’s Death were greatly exaggerated, and I surely helped contribute to it. For sure, after my former wife left me AND her Zephyr publisher responsibilities and commitments so suddenly, the Z did indeed seem doomed. I had no idea how to do a digital version of The Z. That was her great talent along with her extraordinary organizational skills…. I thought it was over.

But so many of you were incredibly supportive and encouraging; finally I crawled out of my black hole and have tried my best to keep The Z alive . The Backbone support from you has been phenomenal. I expected an avalanche of cancellations from The Z’s “sustaining supporters.” Incredibly I had only two–and one of them was Tonya’s mother. Totally understandable. And for sure, others were also skeptical that The Z would survive.

Even my former wife wrote this in a publicly accessible internet site:

“For a while I was publisher of a bi-monthly online periodical—The Canyon Country Zephyr…Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately…a cosmic joke of timing occurred, and things went sideways for The Canyon Country Zephyr. As I’m writing this, the fate of that periodical is unclear. It may be dead. It may be on extended life support. All I can say with certainty is that the Z will not be what it used to be.”

But despite the predictions, The Zephyr is not ‘dead,’ and it’s not on ‘life support,’ and while it may “not be what it used to be,” I’m hoping that with your help and encouragement…and your friendship,” I can, in fact, make it better.

Thanks again…Jim Stiles

Again, here is the link to support The Z: http://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/advertise/indexnewz.htm

As always Jim, well written and right on point.

So informative. I had no idea there were so many dams planned…

Greed and stupidity seem to have been the American way almost from the start. Thanks Jim for everything you do!

Great article Stiles. John Wesley Powell tried to warn people, nobody listened. And personally, I’d keep water for the farmers and tell the new in-migrants to go somewhere else, we’re full!

Having lived not far from the Colorado River all my 95 years, when it was a rushing muddy, often flooding, vibrant dangerous real river, we from early childhood knew to conserve water. Newcomers bring their water using habits with them and then mumble because there’s news of a water shortage! All one has to do is visit Lake Mead and view the huge bathrub ring showing how low the water really is, to know we have reached a serious stage in our water usage. It’s long past time for our powers-that-be to say NO to new building projects. Yet every “vacant” lot in the Las Vegas area is being built upon!; How long before the spigot turns on but nothing comes out?? Thank you, Jiim, for this very excellent portrayal of reality!!

Here’s a song appropriate for the article!

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=-EVoNDr0QFA

Love it

Wonderful story and historical account. Love all the history and subject of Colorado River. I do not see any solutions however in the near future. Sadly like most everything else, there’s a sinking feeling about the train wreck freight headed our way. But great reporting again.

This is a great piece of writing and you’re right in your conclusions. I was born in western Colorado in the ’50’s when the population of Mesa County was under 50,000. Many folks were farmers or ranchers or worked for them like I did. We installed water-conserving irrigation systems even though we lived only half a mile from the mighty Colorado River. We experienced dry years and cut back on water usage. Sometime in the 80’s, some magazines started writing about this picturesque little valley with great weather and affordable housing. A deluge of urban refugees started arriving in every kind of wheeled conveyance, determined to get rid of those nasty industries that keep the country going like farming, ranching and energy. Now the Grand Valley is crammed with over 160,000 people and most of the farming is gone. Sometimes when I visit, I get lost on new roads leading through huge expensive housing with HOA’s insisting on perfect lawns that are irrigated three times a week. Will they never learn….

Another great article. The Z is alive and I’m sure it will be better than ever.

Dear Jim I thought this was a marvelous piece that I thought mirrors maybe the world over.Too many people.

best wishes

Water, water, water! I grew up in Blanding, Utah and live there now. The town has increased in population and continues to do so. The water from snow melt on the Blue “Abajo” mountain was always valued and carefully conserved but that was still giving us a razor thin margin between water in the reservoirs and no water for home use. Recently deep wells drilled into a large pool of ancient water has saved us from dry taps, but how long will that resource last? We have been asked to flush our low capacity toilets only when necessary. I feel guilty using the local car wash to clean my car so it goes dirty more than usual. However, tourists come through town and use hundreds of gallons of our precious water to clean their vehicles. Moreover, the local car wash is even now increasing their capacity to accommodate more vehicles. My town is raising water rates to discourage use. We are almost to a rationing situation. A pessimist might see an allocation system in the future where one has to count the gallons used to shower, wash clothes and dishes. I do use my neighbor’s well for a tiny lawn and some trees that are so important to me.

Jim’s article is spot on, well documented and should be required reading for responsible leaders in western towns and states.

The big drought seems to be on everybody’s minds these days. The dramatic drops in Powell and Mead are newsworthy. As you indicate, we should have known from the very first… I recently read “Science Be Dammed”, published by University of Arizona hydrologists. I had read widely, but had never heard of E.C. Larue. Prior to the 1922 Colorado River Compact, he had done science that correlated old lake levels at Salt Lake to the flow of the Colorado River. He warned over and over, loudly and obnoxiously (apparently), that the years 1880-1900 was a serious drought, but the compact writers only looked at 1900-1920, which were some of the wettest years ever. Larue was hounded out of BuRec because of his insistence. Ironically, he also suggested the series of dams that you documented in your article. He felt that they would suffer less evaporation loss than a single high dam. In later years, paleodendrochronology proved the variable conditions (and declining in terms of amounts of water) since the 400s in the Southwest. Nobody paid attention then. Are they now? Probably not. One thing remains true: water flows toward money.

It’s a sad truth that every lovely and desirable place carries the seeds of its own destruction. Prime example: Southern California. It really must have been close to earthly paradise a hundred years ago. Perfect climate! Snowy mountains and sunny beaches! Oranges and lemons for the picking!…and so on. I remember when St. George was a little Mormon town lost in a red-rock nowhere….now it’s a “metropolitan area”, and you have to get reservations to climb Angels’ Landing. And yet….even before the Oregon Trail, we’ve always been a Westering people. As much as I’d like to build a fortified wall at the Hundredth Meridian, can you really blame people for wanting to get out of Chicago? or Flint, Michigan? or Youngstown, Ohio? or Scranton, Pennsylvania? (Or Oakland, California, for that matter).

The worst drought in a thousand years? How about it’s a permanent reality due to climate change?

Great read, Jim. You hit the nail on the head: “Many New Westerners came here to save it and subsequently ruined it with their sheer numbers and the desire to bring their urban habits with them.” It’s hard to be hopeful about the future of the West. Nature will ultimately teach us hard lessons that cannot be avoided.

The slow effects of the current drought (if it continues for more years) are going to result in some very unpleasant surprises for LV, PHX and Tucson water managers. Wonder what the value of urban real estate and houses will be when there is not enough water in the Colo system and it has to be hauled in cubic containers from $$$ away.

Last mega drought caused an entire civilization (Fremont and other native groups) to abandon their villages and head elsewhere.

Brilliant research, writing and presentation.