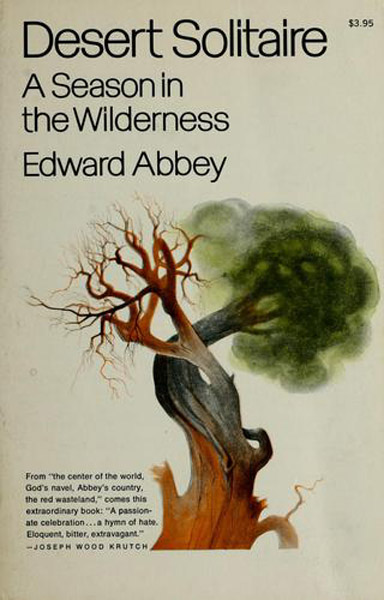

Some of my first images of Glen Canyon were through the eyes and camera lens of Philip Hyde. Years earlier, I had discovered Edward Abbey’s book, “Desert Solitaire,” and had read his account of a final float down Glen Canyon, before the dam flooded it and created the Lake Powell reservoir. Abbey’s narrative created a montage of images in my mind of this once magnificent and relatively unknown part of the Colorado Plateau, which now resided under 700 feet of stagnant water.

“Desert Solitaire” was published in 1968, but living far from the canyon country in Kentucky, I did not discover the book

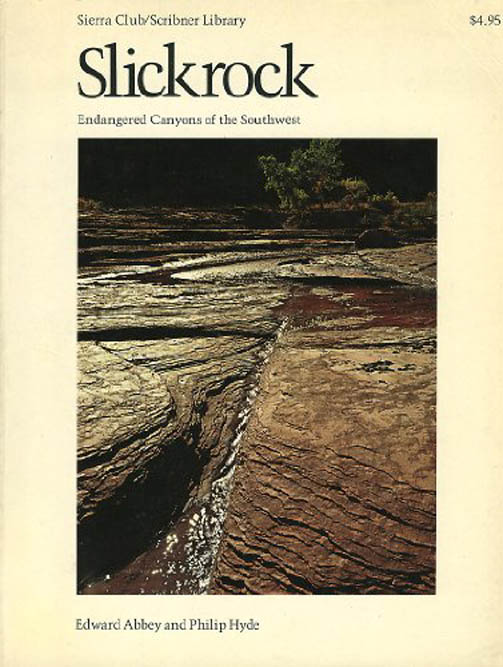

until three years later. In October 1971, I was at my local bookstore, now a full-fledged Abbeyphile, searching for another paperback copy of Abbey’s book for a friend. As I perused the shelves, I came upon a magnificent, recently published, hardbound coffee-table book called “Slickrock.” I immediately saw Abbey’s name as one of the co-authors, but I had never heard of his collaborator—Philip Hyde. At the time I was as broke as I’ve ever been, and the $25 price set me back, but I was determined and so I invested about 20% of my net worth and bought “Slickrock.” I never regretted it.

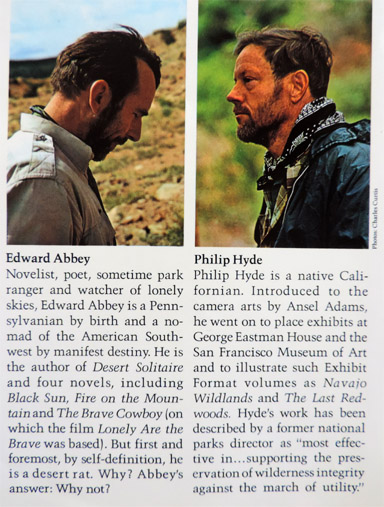

Two epiphanies would come from that moment. On the back jacket, I read both biographies and realized that Abbey had written the 1956 novel “Brave Cowboy,” upon which the 1962 film, “Lonely are the Brave” was based. I had seen that movie on television, a decade earlier, and it had a profound effect on me and on my future. To this day, it’s one of my favorites. The bios also included photos of both men. I studied them closely and decided to learn more about Mr. Hyde as well.

I soon realized that Philip Hyde was one of the most recognized and honored landscape photographers in America. He had been part of the conservation movement for decades, long before most of us knew there was a “movement” to begin with. I hoped that someday my path would cross, hopefully somewhere Out West, with both of these men, who were now heroes and role models for me.

///

The good luck that came my way in the next few years still amazes me. My dog Muckluk and I headed for Utah in my beater VW bus in 1975—the future was completely unknown. I had no plan. No prospects. I threw caution to the wind and hoped for the best. Within six months I had moved to Moab, met and befriended Ed Abbey, landed a seasonal ranger job at Arches National Park, made many new friends, and received an invitation from E.P. Dutton Publishers in New York, at Abbey’s insistence, to illustrate his next book of essays, ultimately titled “The Journey Home.” Those were happy times. Almost surreal. I don’t think Ive ever experienced a period of my life quite like it.

In the Spring of 1978, I was into my third year rangering at Arches. I lived at the Devils Garden campground, in a government trailer that some tourists always thought must have been Abbey’s. On one very cold, snowy spring morning, two men knocked on my door to report an abandoned campsite. They were leaders of a photographic workshop that had been set up in the small groupsite, just adjacent to the campground entrance. What they described to me was certainly troubling. While leading their students cross country through some sand dunes, about a mile from Landscape Arch in the Devils Garden, they had discovered the site. An open pack and sleeping bag lay in the sand, half buried by the March winds. Various items lay scattered about and an open dog-eared copy of “Desert Solitaire” was tucked inside the bag, bookmarked to page 167. Clearly, the backpacker had walked away from his site and never returned.

The discoverers of the site only identified themselves as Art and Phil, and the three of us scoured the canyons for hours in search of the missing camper. But before the camp had been found, days had obviously passed and even footprints had been blown away. We emptied the backpack, searching for clues and only found a scrap of paper with a doctor’s name and the town of Springfield. The paper was torn and we could not determine what state it referred to. But it was a start. I reported the information to my boss, Chief Ranger Jerry Epperson and we continued our futile search.

As the three of us finally gave up and made our way back to the campground, a light came on in my head. For the first time I noticed the striking resemblance between the man who had reported the missing camper and the author’s photograph in my beloved “Slickrock.” I stopped dead in my tracks. Puzzled, Art and Phil stopped too.

“Wait a minute,” I finally said. “You’re not Philip Hyde are you?’ He smiled modestly and said, “Just call me Phil.” He never felt the compulsion to tell me that he was one of the most revered and respected photographers in the world. He was that kind of guy. When we got back to the campsite, he and Art Bacon and I talked for hours. I told Phil about my investment in “Slickrock,” and he almost looked embarrassed. Art was a highly regarded man with a camera in his own right, and is still hard at work in 2022, producing magnificent images (check his website). But we were all more interested in the future of the American West. I asked Phil about Abbey who noted that he liked him and admired his work, but found Ed to be a tad reticent when it came to conversation. It was true that sometimes Abbey was a tad restrained.

When I got ready to leave and resume my feel collection duties, Phil reached into his wallet and handed me his card. He lived in Taylorsville, California and told me to stop by any time. We shook hands all around and they prepared to break camp. . I held onto the card and put it in a safe place.

But just as Phil and Art were saying our farewells, I got a call from my boss via the two-way Motorola radio. Jerry said simply, “Discontinue your search. The missing hiker has been found.” I was shocked and asked, “Where was he?” The chief ranger replied, “Missouri.” As it turned out, the hiker had wandered away from his campsite a few weeks earlier, but then couldn’t find his way back to it. After searching futilely for several hours, he finally gave up and went back to Springfield, Missouri. Phil and Art and I collectively shook our heads. The future of inexperienced bonehead recreationists was already upon us. Ultimately I hiked out to the site and carried his 50 lb. pack to the trailhead and we shipped it to Missouri, paid for by the U.S. Government.

///

Eleven years later, when I started The Zephyr, I knew exactly where I had stored Phil’s calling card, so I signed up Phil Hyde as a complimentary Lifetime subscriber. A few months later, to my surprise, I received a card from Phil. He still remembered our encounter from 1978 and wrote to thank me for the complimentary subscription and to wish me well in my endeavors. Over the years, he became a Zephyr supporter and contributed a few letters to the Feedback page.

He even became personally involved in some of The Zephyr stories that I had covered, especially public lands issues. Phil was passionate about preserving and protecting those lands but he also made a living as a photographer documenting the pristine nature of what still remained wilderness. Keep in mind this was almost half a century ago, before social media and Instagram. Commercial photography was a real niche profession, reserved for the very few with the talent and the technical skills to produce fine photographic art. Phil was the best. But there was a new generation of photographers out there and more opportunities via magazines to get them published.

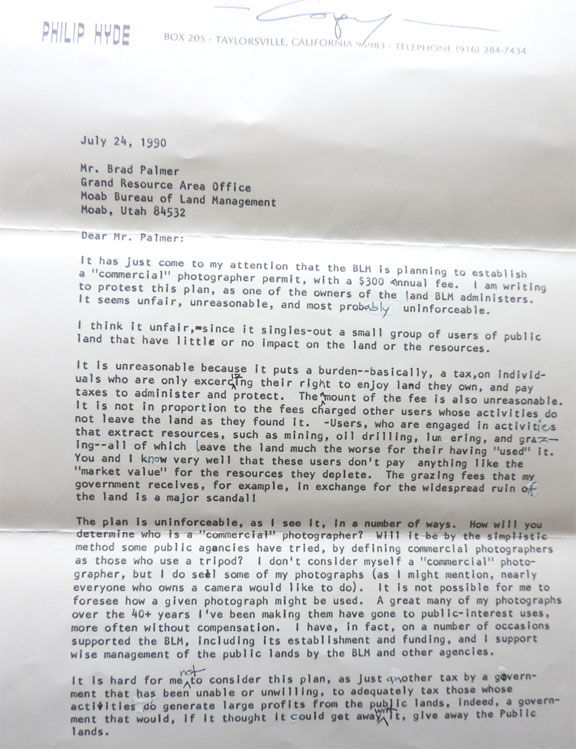

I had only been producing The Zephyr for a couple years, when I came across a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) news flash; it was about a new restrictive regulation and associated fee that was so absurd in its concept that I had to go visit the local BLM bureaucrat in charge, just to be sure I was interpreting this new “rule” correctly.

The new regulation stated that anyone who was a commercial photographer, or possibly aspiring to be, who took pictures in Southeast Utah, was required to obtain a $300 permit from the local office in order to continue shooting. The language was vague—did it mean known commercial photographers or did it mean any citizen photographer who took a picture on public lands with the hope of possibly selling it to a commercial enterprise, be it a magazine or even a business? I decided to ask the BLM official who invented the rule. Marty Von Kookenberg (not her real name) greeted me warmly when I stopped by her office for clarification. I had honestly expected her to diss the idea and blame it on some government functionary back in Washington, but instead she stood four square behind the idea.

“You have to understand, Jim,” she patiently and somewhat condescendingly explained, “if people are going to make money off our public lands, they need to pay for that right.” But I persisted. “How would they even know if they’ll be successful in selling their photographs? You’re suggesting that even the motive of taking photos for profit should require a permit.” To my astonishment, she agreed.

Finally, being the smart ass that I sometimes I could be (I’m much less combative these days). I asked a ridiculous question that I assumed would generate a chuckle. I asked this…

“Okay, so let’s say you’re standing on Main Street in Moab and you’re taking a photograph of the buildings and the traffic, but in the far distance are the two thousand foot sandstone cliffs of Moab’s West Wall. That land is public–all administered by the BLM. Consequently since half the photograph is on private land and half of it includes public lands, would a photographer be required to pay half the fee?”

I fully expected Marty to break out laughing. Instead she furrowed her brow and gave it a deep think. After a few moments she said, “Excellent question, Jim. I will need to contact the Washington office and get a ruling on that.”

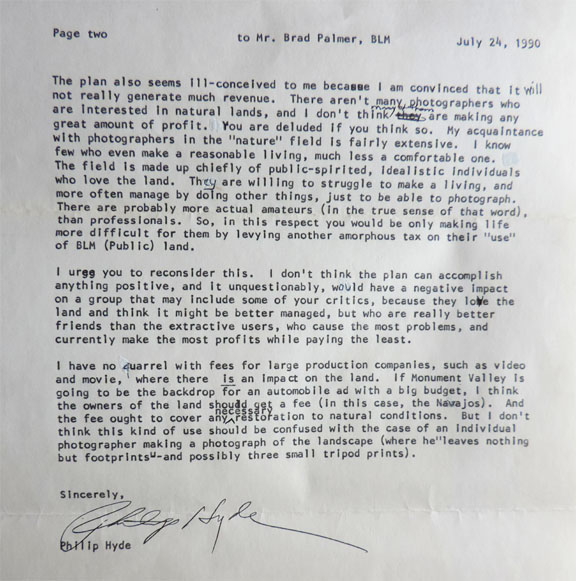

I sat there, my eyes glazed and my mouth agape. I replied, “Okiedokie Marty. I have all the information I need.” I left quickly. I was clearly dealing with crazy people. I wrote up the story and the BLM comments and put them in the next Zephyr. A week later, I heard from the great Phil Hyde. Actually he sent me a card and a copy of the long letter he had sent to the BLM in care of the resource manager. Hyde was pissed. He wrote, in part:

“It has just come to my attention that the BLM is planning to establish a ‘commercial’ photographer permit, with a $300 annual fee. I am writing to protest this plan, as one of the owners of the land that BLM administers. It seems unfair, unreasonable, and in my mind most likely unenforceable…

“…The plan is unenforceable, as I see it, in a number of ways. How will you determine who is a ‘commercial’ photographer? Will it be by the simplistic method some public agencies have tried, by defining commercial photographers as those who use a tripod? I don’t consider myself a ‘commercial’ photographer but I do sell some of my photographs (as I might mention, nearly everyone who owns a camera would like to do). A great many of my photographs…have gone to public interest uses, often without compensation. I have, in fact, on a number of occasions, supported (and donated to) the BLM…

“…I have no quarrel with fees for large production companies…if Monument Valley is going to be the backdrop for an automobile ad with a big budget, I think the owners of the land should get a fee…But I dont think this kind of use should be confused with the case of an individual photographer (where he “leaves nothing but footprints”—and possibly three small tripod prints.”

Phil signed his letter, “sincerely,” and he surely was. Eventually the idea was dropped, based I believe to a great extent, on Philp Hyde’s protests. (and note, I have no idea whether now in 2022, the fee hasn’t at long last been implemented. I can no longer bear to follow the politics of Moab and surroundings).

///

Hyde and I didn’t agree on everything. He was a strong supporter of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, proposed and proclaimed by President Bill Clinton in 1996. But Phil had not been to Utah in years and had not seen the creeping cancerous growth of the Industrial Tourism Industry in Utah. I was ambivalent about the designation. It was intended to stop the Andelux Coal Company from moving forward with a strip mine on the Kaiparowits Plateau in Southern Utah. Though proponents argued that there were 400 years of coal to be extracted from the plateau, I argued that there was a fair chance we wouldn’t be using much coal in the year 2496. As it turned out, the mine was never built which probably saved the company millions of dollars as the coal industry continued to plummet. But the tourists came—in droves over the next 20 years. Escalante is not the same town it was in 1996. But the Industrial Recreation Scourge stretched much further than Garfield County. There is no need here to regurgitate the details of the Insane Tourism Plague and its devastating impacts on much of Southern Utah and the rest of the Rural West.

But this was 25 years ago. The threat wasn’t as apparent, and Phil still adhered to Abbey’s admonition: “The idea of wilderness needs no defense; it needs more defenders.” Hyde, like Abbey, never imagined the amoral kind of recreation ethic that would profoundly change the West decades into the future.

Still, like so many other friends of mine back then, our differences of opinion never affected our friendship.

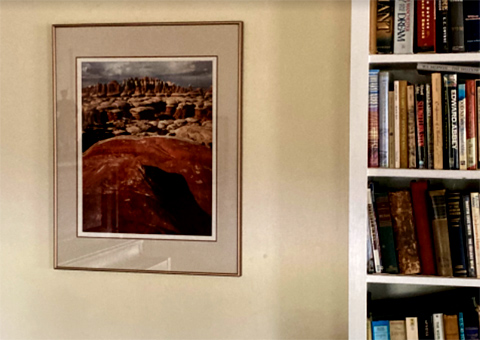

In fact, a year later in 1997, a short letter from Phil arrived. He wrote, “I’ve always felt a bit guilty that I’ve never paid for my subscription to The Zephyr over all these years. I was wondering if I might re-pay you in some way. Would you consider one of my photographs as a trade?”

I was speechless. A week or so later, a large black portfolio arrived by mail. In it was a spectacular image of the Needles country in Canyonlands, signed by one of my heroes, Philip Hyde.

“The print is a Cibachrome of the Needles, from Elephant Hill, vertical— I hope that a vertical will fit the space you indicated, but I am a little distressed that I’ll be replacing your Aunt Nora. You’ll have to show me that the next time I get to Moab (The painting Phil refers to is a scandalous nude of my great Aunt Nora Montfort, painted by her then-husband Fred Haspell in the 1930s. The work had been the scandal of the Montfort Family and they willingly gave it to me.).”

Phil added modestly. “Maybe you could put the Needles on the back of Aunt Nora, so you could be prim on occasions demanding that–you rotate the picture, when expecting important (or undiscriminating friends) …(Freudian slip—does your Aunt Nora have one handy—a Freudian slip, I mean?)”

In the same letter, he also mentioned Katie Lee. “Never met her, though we should have crossed paths on some river or other. Ardis (his wife) and I are fans of hers. We play (her music) for river-running friends, mostly ignorant youngsters who haven’t heard it. It sure captures the spirit of the river!”

Hyde, who loathed Lake Powell and the dam that flooded Hetch Hetchy near Yosemite, added a handwritten postscript.

“Dave Brower says he has a plan to restore Hetch Hetchy. I’d like to see one to bring back Glen but gradually—no dam busting that would flush out Grand.” Then he grew a bit more philosophical, noting in a way that our presence here is just a blink of the geological eye. He concluded:

“We’ll come back a few millennia from now & watch Colorado erode the Glen away…one grain of sand at a time. But it’ll happen.” He clearly opposed Abbey’s “monkey wrench” philosophy, though I was never sure Ed took himself seriously either.

Hyde’s Needles Cibachrome is still one of my most treasured possessions and has an honored place in my home.

In the early 2000s the letters from Phil were less frequent but in one note, he acknowledged that his eyes and his health were beginning to fail him. I cannot imagine anything more painful than a brilliant artist like Hyde, whose visual sense meant everything to him, losing his vision. Then the letters stopped.

A couple years later, I heard the news that Phil Hyde passed away on March 30, 2006 at the age of 84. He left behind a stunning collection of images, of a land he loved for a lifetime and beyond. I will remember him equally for his gentle manner and his quiet integrity. And his enormous generosity. He was another man whom I revered and loved like a friend, not just for his talent but for his humility and his decency and his kindness toward others. Men like Phil Hyde are vanishing from this world. It is our great loss.

Jim Stiles is publisher/editor of The Zephyr.

Jim,

I read your memoir of Phillip Hyde with interest. As a professional photographer with a deep love and appreciation for the landscape, not to mention public lands, Hyde was one of my heroes also.

What also stood out in your eloquent and provocative story was your long-ago cross-country ramble in a VW bus in 1975. I too share such a ramble, only I was making my own migration from Tidewater Virginia as an upcoming junior at the University of Colorado and it was 1971. I lived in my van for the entire summer. After stowing my possessions in Boulder, I continued to wander, up through Yellowstone Park and on into Montana where I visited a female classmate whose uncle was the Dean of the divinity school at Yale and owned a home on Flathead Lake out of Polson,MT. From there I made my way down to New Mexico where I searched for my old college roommate and chased a few comely hippies girls.

I digress.

You honored Hyde and as a photographer who has long felt that I occupied a tenuous existence somewhere off to the side, it’s good to see such an artist receive his due.

excellent story, brings back a lot of memories even though I never knew these folks. I did see the pictures and read the books. Just as I found myself wondering how many more old Moab stories do I need to read, you come along and tell a new one I needed to hear.

chute/shoot: azz yoozyoo-all, i have nuthin’ to add to the previous sentimentations & such. still — reading thru’ yet another excellent JStiles reminiscence with all the history, the side-bars, the sand-bars (jes’ kiddin), the implications — briefly makes me FEEL like i’m there in the time and place(s) you describe. thanx again ~

Hyde is right in there with Eliot Porter who also did a book with David Brower about Glen Canyon, which was a project that tried to visually persuade people to save Glen Canyon. Unfortunately the project didn’t work, but possibly made more people aware of what was happening.

I was able to find a copy of Slickrock on Amazon for considerably less than you paid for your original copy.

Thanks for this article in particular and everything you do in general.

Gary O’Brien

Photographer

Tucson, AZ

704.661.1469

FB: garyobrien1

IG: garyobrien321

http://garyobrien.com

“May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the

most amazing view. May your mountains rise into and above the clouds.”

-Edward Abbey, naturalist and author (1927-1989)

Touching. Phil is a treasure. Thank you for sharing his letters and photograph. But tell us more about Aunt Nora please.

Slickrock was one of those iconic books for me. I, too, bought it as soon as it was published, having already been indoctrinated to the experiences of SE Utah in a slightly abbey-esque way. I did not meet either author, but feel connected to both. And in my recent 4 seasons as a Park Ranger at Natural Bridges NM (going back for another short stint this August), I never fail to take Slickrock with me, and have found its pages and passages very resonant.

Terrific article, Jim. I’ll pony up a contribution for continued work later this summer.

I enjoyed the memoir of Philip Hyde…I own Slickrock. I think I’ll pull it out and read it with a new perspective.

Thanks for the write up on Phillip. I, too, spent a significant portion of my available funds on a copy of Slickrock, as well as his Glen Canyon Portfolio. I’m looking forward to watching the canyon re-emerge!