When will environmentalists acknowledge their own contribution to the destruction of the wilderness they claim to love and want to protect?

EDITOR’S 2022 PROLOGUE: By the spring of 2001, I had become disillusioned with my very own allies–the mainstream environmental organizations that oversee the use and abuse of public lands in Utah. I had begun to see real impacts coming from the tourist industry–what we would come to call Industrial Strength Recreation and Tourism. And yet most of these groups turned a blind eye to those kinds of impacts. In fact, they embraced this new burgeoning economy as a way of replacing the old west economy of ranching, oil, gas development, and mineral exploration.

Further, their opposition to these “Old West” industries had taken an ugly personal turn. It wasn’t just that they hated cows—they hated the ranchers who raised them. The environmentalists didn’t just loathe the oil wells, they hated the people who worked on them—from the CEOs to the tool pushers. It was really the beginning of the cancel culture mentality that pervades American life now. What was most difficult to swallow, for me at least, was the utter hypocrisy of environmentalists’ arrogant condescending attitude toward Old Westerners and their way of life.

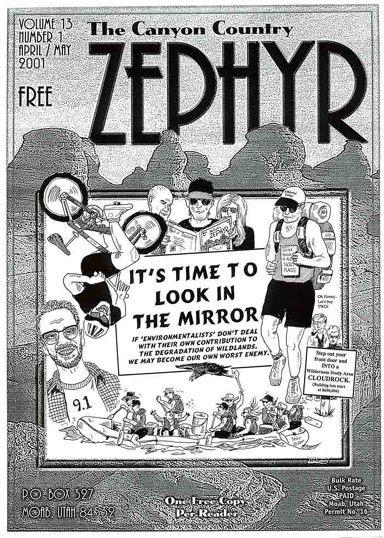

To me, the situation was just getting uglier and uglier, as the landscape of Southeast Utah continued to be degraded. And much of the damage was coming from “our” side. I dedicated the entire April 2001 issue of The Zephyr to this cover story. I called it: “Its Time to Look in the Mirror.” Here are major excerpts from those two articles, written almost a quarter century ago…JS

PART 1

In the Spring of 2001, the polarization between the Rural West and the New West could not be more profound. Or more counterproductive. If it gets much worse, the consequences for the land–the wild country that both sides claim to cherish and revere–is destined to be the true and everlasting loser of this hopeless fight. And it’s about time that BOTH sides come to grips with their own culpability, and their own contribution to the ongoing degradation of wildlands in the West.

And yes…I’m talking about US. Environmentalists. Eco-Warriors. Non-motorized recreationists. It’s time we take a long hard look into the looking glass and acknowledge our own sins. This is no longer the black and white, “us versus them” moral war that we have attempted to promote for the last 20 years. We cannot, with a straight face and an honest heart, continue to insist that the environmental movement represents the knights on the white horse, here to save our wilderness from the Rural Americans who we portray as ignorant at best, downright evil at worst.

Maintaining the Rural Stereotype

We are now contributing our own kind of destruction to the last remnants of the Wild West. Our recreation, our money, and our sheer numbers are poised to do the kind of long-term damage that should be setting alarms off in our heads. The changes we’re making may be harder to detect and more insidious. But in the next 50 years, we are poised to recreate the Western landscape in ways our cowboy cousins could never imagine.

Certainly environmentalists can always find ignoble adversaries out there in the Rural West that will lend credibility to the myth we have created for them. We don’t have to wander far to find the reckless damage caused by a small minority of rural yahoos (not to be confused with urban yahoos) who love to show what they can do to pristine desert with an ATV.

But it’s not fair to paint all, or even most, rural Westerners with such a broad stroke. I like these guys–or at least many of them. I enjoy the diversity and the opportunity to see and learn a new perspective, even if I vehemently disagree with it. Ultimately the greatest failing of the environmental movement may prove to be its self-imposed isolation from everyone else, and its inability to listen to a different opinion with an open mind. Its vision is so specific that it cannot see the bigger picture.

Both sides have become victims of their own rhetoric and their own ideology. They are so entrenched because they have no contact with each other. If professional environmentalists only talk to other environmentalists, and cowboys only talk to cowboys, what chance is there for anyone to learn something? It’s a self-inflicted stalemate on both sides.

As the Old West becomes the New West, many have come to regard the rural lifestyle with contempt and ridicule, content to see it vanish from the American Landscape. Someone could make the argument that it’s a case of justice and retribution. More than a century ago, White Americans came West and encountered the Native American culture and could detect no value to it…none. And so we set out to obliterate that culture until now, a hundred years later, Native Americans across the country struggle to maintain their identity and integrity. It was a form of cultural genocide.

Now in the 21st Century, many urban newcomers to the Rural West–New Westerners, if you want–express the same derogatory opinion of the descendants of those first white settlers. Many of us can see nothing in the rural culture worth saving.

It’s not that I haven’t had some awful experiences with the Rural West over the years. I learned early on that identifying myself as an ‘environmentalist’ in San Juan County, for instance, would not win me a lot of new pals at the local hardware store. But when we can all get past the labels, I have also been impressed and moved by the generosity and kindness of those same individuals. Simple acts of kindness must count for something out there and I certainly cannot ignore them.

Some will argue that I’ve just been lucky. Or delusional. Or that it doesn’t matter. I recently shared some of my experiences with one of my favorite environmentalists and he called me “a brainless idiot…What has that got to do with wilderness?” he yelled. And it’s true that my buddy has had more than his fair share of abuse from Westerners who’d like to see a Wilderness Society representative heading east with a Sierra Clubber under each arm. In parts of the West, from Ely, Nevada to Escalante, Utah, it has become ugly, and I make no effort here to defend those people in any way. I become particularly discouraged when I see Rural Westerners, who should know better, and who are better, failing to condemn the actions of the foolish few who give all of them such a bad name. But then how can we expect any different behavior from them when we do exactly the same thing ourselves?

The Great Contradiction

And isn’t that the point? How can we continue to condemn the irresponsible and unacceptable behavior of people that we believe are damaging our irreplaceable natural resources, while ignoring or playing down the ever-growing destruction caused by us! Non-motorized recreationists–hikers, group hikers, bikers, climbers, rafters, kayakers, runners, action tour groups!–all those enlightened sportsters who wrap themselves in the environmental flag and send money to the Sierra Club while wreaking their own kind of enviro-havoc?

The West has changed dramatically in the last decade. A good argument could be made that the New West is at least, in part, a product of the environmental movement. More than ten years ago, Rural Utahns produced a document called the Leaming Report–it was funded by member counties of the Utah Association of Governments and made the case that wilderness in Utah would destroy the rural lifestyle, bring an end to the extractive industries in the West, and cost rural counties millions of dollars in lost revenues.

In this very publication, environmentalists countered immediately with their own observations. Among them was the claim that tourism, linked directly to wilderness designation, would create a new industry in the Rural West and would bring enormous benefits to the region. “Designated wilderness,” The Zephyr article read, “acts like an advertisement that says: ‘Here is a treasure house of environmental amenities!’ …This ‘advertising’ attracts people that economists call ‘amenity migrants,’ causing twice the growth in rural areas with designated wilderness than in areas without wilderness.”

These pro-wilderness comments from 11 years ago could not have been more prophetic. But that is the route we took–instead of taking the noble route and simply stating that the designation of wilderness was the right and courageous thing to do, we tried to promote the economic advantages of wilderness. Wilderness Pays in Spades! Since then, the cumulative effect of billions of footprints and tire tracks, and the transformation of rural communities into ‘tourist towns’ from millions of ‘amenity migrants’ have left an indelible mark. In short, the natural beauty of our land was packaged and commodified and sold. By us. We’re not just talking “surface rights” anymore. This goes right to the soul.

Now, we have created a new kind of speculator in the New West–the enviropreneur. These are men and women who see a way to make money out of the beauty of the land and who pay lip service to environmental issues in order to enhance and legitimize their own credibility. Too often, it seems all anyone has to do in Utah is to proclaim for the Utah Wilderness Coalition’s 9.1 million acres proposal to gain serious consideration as a protector of the land, despite the obvious contradictions.

No…that’s not quite right–we won’t acknowledge the contradictions. We environmentalists are scared to death of crossing our own constituents. This isn’t consensus building…this is the politics of acquiescence, pure and simple.

It’s been difficult for environmental groups in Utah to acknowledge these facts. Why? Because these recreationists and enviropreneurs represent a significant portion of the environmental groups’ membership. They will privately acknowledge the threat but they don’t want to say it out loud. “Look,” one of my friends explained to me recently, “We already get accused of wanting to ‘lock up’ the land for the few. If we now come out and express opposition to these guys, we’ll be accused of being against everybody.”

But I don’t agree; nothing knocks the stuffing out of credibility like hypocrisy. How can anyone take us seriously when we turn a blind eye to our own contribution to the destruction? We must speak up and speak out against anyone who uses the land for profit at its own expense. If we’re going to criticize an irresponsible rancher, then what about the irresponsible tour guide? Why don’t we discourage overuse of pristine places by hikers and climbers?

It has been ‘explained’ to me that the fight over non-motorized damage will just have to wait until we deal with these other threats. But that’s like the captain of the Titanic saying, “It’s too dark to worry about icebergs now…wake me in the morning when I can see the damn things.”

Some environmentalists have recognized and grieved over these contradictions for years. In 1991, Ken Sleight recorded his oral history with the University of Utah at the Marriott Library. Part of his comments from that interview reflect his concerns:

“I always feel like you can use a resource, and if you’re damaging it then you learn how to take care of it…When I took the Sierra Club down the Escalante once, they had fifty Sierra Club people coming on that trip. I was going to carry all their gear and so forth. So I had to get twenty-six horses and seven wranglers to take those people down the Escalante. I realized at the time that with all those horses I was really exploiting the area because it is not good for the sand banks; it was not good for the ecology of the area to have that big of a group. I went specially to San Francisco to talk to the Sierra Club, and I said, ‘This is not good for the Sierra Club and so forth.’ Well they dropped me from taking the trips anymore because I would refuse to take big trips.”

Those were comments made by Sleight a decade ago about an incident that occurred in the early 1970s.

More contradictions…

Utah environmental groups spend an enormous and frustrating amount of time trying to stop oil and gas exploration on the Colorado Plateau. I know that these endless battles can drive SUWA’s field reps to tears at times. But, in a way it’s no wonder–ten years ago, the Utah Wilderness Coalition was trying to keep the extractive industries out of its original 5.7 million acre proposal. Now with the UWC proposal exceeding 9 million, the challenge is even more daunting.

But who needs the oil? Old timers have been reminding us forever that we use that oil too, and we’ve rolled our eyes and sneered smugly as if their comments were somehow beneath us. But why do we dismiss those comments? Energy costs associated with tourism are enormous. We take pride in the fact that we’re non-motorized recreationists, and I have to laugh. We climb into our gas-guzzling SUVs and travel hundreds or thousands of miles so we can recreate for a day or three in a non-polluting fashion. Our defense is weak.

Common Concerns…

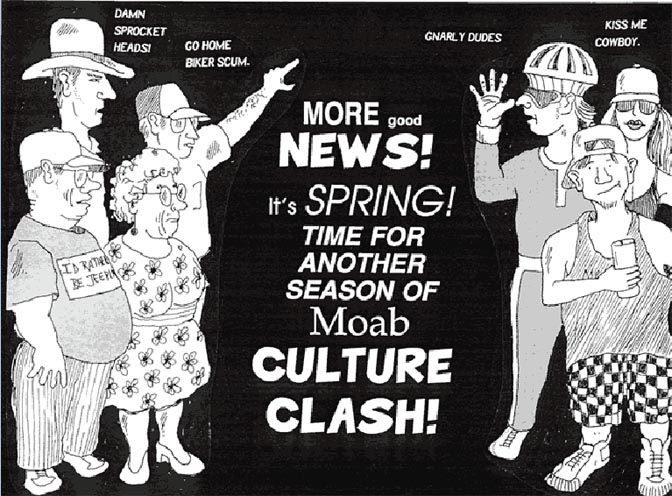

Consider an example that cries for consensus from both sides. In San Juan County, most of its citizens will, if you tell them you’re from Moab, shake their heads and say, “We sure don’t want to end up like you guys.” And they don’t. They can’t bear the thought of it. But some of their elected officials and some of the bureaucrats in the BLM and Forest Service continue to make decisions that are putting towns like Blanding and Monticello in a position to become just that.

In particular, new roads and “improved” roads in San Juan County will simply create wide-lane conduits for more tourists. Last summer, San Juan County, in conjunction with the Forest Service, dramatically expanded the size of the Blue Mountain Road. Hundreds of Ponderosa Pines were cut down, the shoulders denuded, the pavement widened and the curves straightened. It paid a few contractors well for a season and will create an improved road to the Needles.

But to what end? Who benefits and who likes the road? Many Monticello citizens have privately expressed dismay but will not confront their elected leaders. Why? Because they don’t want to side with the environmentalists. Farther south, the Forest Service is already looking at the South Cottonwood Wash road to Elk Ridge and the connecting road over the Bears Ears to Natural Bridges. They want to upgrade the road, one step at a time, over a few years, until one day, we’ll find the road paved and San Juan County citizens will find themselves another step closer to the Moabization of Blanding. This is a battle that could be fought shoulder to shoulder with San Juan County citizens and won. But if we’re ever going to stop that kind of reckless road building, it will absolutely require that kind of cooperation.

As for ranching, my enviro-pals will look me squarely in the eye and swear that they don’t want to put any rancher out of business and they’ll laugh at the “cows versus condos” debate. It may be true that environmentalists want to eliminate public lands ranching, they’ll concede, but they say they don’t want to put the ranchers out of business. Of course, you couldn’t hope to find a more disingenuous argument–without the allotments, the ranches will fail. As for the condos, of course they won’t be built on the grazing allotments, but they will eventually replace every alfalfa field in the Rocky Mountain West. What a vision for the future that is.

I’ve even heard it said that what’s happening to ranches is inevitable and has nothing to do with the urbanization of the Rural West, as if our efforts are performed in a vacuum and disconnected from the real world. But regardless of who is to blame, we environmentalists should NOW be doing everything in our power to work with the ranchers to find alternatives to development. After all, the Nature Conservancy can’t buy all the agricultural lands in the West.

Where the Line in the Dust Needs to be Drawn

I keep thinking about my enviro-pal’s “brainless idiot” comment. He could not understand what being a nice guy had to do with land stewardship; in fact, when all the chips were laid on the table, he stated his case quite honestly–the only way we will be able to preserve the remaining wild country of Utah is to close the roads. My retort was that we’ll never be able to get all those roads closed and that our own hope is to increase the sensitivity of ALL people to this fragile desert, whether it’s ‘designated wilderness’ or not. I absolutely support wilderness and I also absolutely support the respectful and even reverent treatment of land outside those politically designated wilderness areas.

After 20 years of being an equal opportunity antagonist, I’ve now experienced corruption, dishonesty and deceit from both sides of the aisle. I’ve observed the crooked politics of dishonest Good Ol’ Boy politicians and I’ve swallowed a big dose of arrogant, elitist yupster enviropreneur dishonesty as well. But because we’ve drawn these lines in the dust–trenches is more like it–many of us feel obligated to defend our ideological peers, even when we know we’re wrong! We refuse to acknowledge just how stubbornly similar the two ends of the spectrum have become.

Rural Westerners look at the damage caused by oil and gas and overgrazing and logging and shrug and say, “So what?” Then we look at the impacts from tourism and condo developments and the urbanization of rural communities and we shrug and say, “So what?” How can we mock the insensitivity of the other guys when we do exactly the same thing?

Perhaps consensus between the environmental community and the Rural West is being too optimistic–consensus calls for a conclusion and a resolution of differences and I can’t imagine such a feat in the near future. But dialogue is not only possible, it’s essential, if for no other reason than to remind ourselves that we’re all human. There’s nothing like a good face-to-face argument over a cup of coffee to de-mystify the opposition. What do any of us have to lose?

It’s time for a new line in the dust, one that makes sense and recognizes the common bond that many of us share but try to deny because the labels don’t fit. To hell with labels. Environmentalists v anti-environmentalists. Liberals v Conservatives. Urban v Rural. These labels are just getting in the way and preventing any kind of united front against the one true threat that all of us who love the West should unite against.

It’s Greed, plain and simple..

Follow the money. It has been like this forever and if we don’t acknowledge our common adversary–the voracious and insatiable quest for material wealth by the few–we will indeed transform the Rural West into the money machine they want it to be. But all of us who have come to live in the Back Blocks of the West, simply because we love to be here, must find a way to speak together against those who simply see the beauty of the West as a way to make a buck…another buck. To these people, you can never have too many bucks and they’re using us, conservatives and liberals, to reach that end.

If we ever could put aside the acrimony, what could we hope to accomplish? I think we can find a consensus (someday) on the future of our public lands. We have to understand that respect for all public lands, regardless of their specific designation, is critical to the survival of the West. We can’t create islands of wilderness and abandon the rest of the land to the reckless and destructive whims of the foolish few. And that is exactly what our side is doing. We are so specifically tied into this wilderness battle, that we’ve abandoned the rest of the land.

Finally, the only way we’ll ever be able to have an honest exchange with our environmental adversaries is if we can be honest with ourselves. But we weaken our own position if we speak less than candidly—the unvarnished truth is a powerful ally. Walt Kelly’s “Pogo” first said it 30 years ago, and it’s become a cliche’, but the truth is what makes them cliches. When Pogo said, “We have met the enemy and they is us,” he knew what he was talking about. Are we wise enough to acknowledge the truth as well?

PART 2

NOTE: what follows here is a discussion of the impacts on wildlands in 2002. Imagine that all these kinds of destruction were already happening, almost a full decade BEFORE smart phone and social media and Instagram and facebook. The threat was clearly there, waiting to explode. And that is exactly what has happened in these last 21 years…

THE FUTURE RECREATION THREAT

Twenty-five years ago, as the wilderness movement was just beginning to gain momentum, environmentalists prepared to do battle against those who were mostly likely to destroy the dwindling wildlands. For most of us, the enemy was easy to identify–the extractive industries in the West posed a constant threat to the deserts and mountains of the region. Cattle ranching, strip and hard rock mining, oil and gas exploration, clear-cut logging–all of these industries had, for almost a century, enjoyed carte blanche access and approval from the government to exploit the natural resources of public lands. Now, finally, these operations were receiving the scrutiny and criticism that they had always deserved.

In the early 1980s, I still remember a flurry of seismic activity by the oil and gas companies along the edges of Arches National Park. As a seasonal ranger, I took a dim view of the work. The crews dozed new roads for their equipment right to the park boundary. Many of those tracks are there today, almost twenty years later.

If there was any consolation in all this, it was the fact that, once the seismic crews had done their work and recorded their data, they left. The heavy equipment was loaded and hauled away and, despite the scars the desert otherwise returned to normal. The silence came back as did most of the critters that had been run off by the noise.

We had hoped and even assumed that those equipment tracks would now slowly disappear as the desert began the slow process of restoring itself. But it never got the chance. Today many of those tracks are used regularly by mountain bikers. The scars never had the chance to heal and the silence never really returned, at least not in any way similar to two decades ago.

Recreation is now leaving its own ugly scars.

The increasing impacts from non-motorized recreation are only beginning to be recognized by many environmentalists as a real threat to the future of wildlands. The last decade has brought staggering increases in visitation to places like the canyon country and we’ve heard the national park statistics–at Arches National Park, visitation has jumped from less than 300,000 in 1976 to numbers approaching one million in 2000. (NOTE: In 2022 it’s approaching 2 million) Numbers are similar at other parks in the region. But park statistics don’t even begin to tell the true story of public land use–in the Canyonlands area, for example, those vast oceans of BLM and Forest Service lands that surround the parks were virtually untouched by recreation before 1985. If the public lands could survive Jeep Safari, they were pretty safe for another year. A few jeepers made their way onto the back roads and jeep tracks; otherwise it was pretty quiet out there. Virtually nobody hiked in the BLM backcountry and mountain bikes had not yet found their way to Moab. Guided tours were limited mostly to jeep excursions and river trips.

Today, on any given weekend, the dirt road junctions with US 191, north and south of Moab, are choked with bike-toting SUVs and Saabs. Tens of thousands of non-motorized recreationists launch their non-polluting vehicles onto old dirt tracks left from the uranium age. Even off-trail backcountry gems and “secret” places, unknown to most until a decade ago, are visited daily. Surely the wilderness is not what it used to be.

This assault on the wild country is a bit more insidious than the groan and crunch of a D9 Cat or a Husquavara chainsaw. The degradation to the land is there and getting worse by the month, but doesn’t bear the catastrophic scars of heavy equipment. The physical damage comes from footprints and bike tracks, stomped into the desert over and over again, by thousands of recreationists who have no idea what damage they’re causing. And they are attacking an element of wilderness that is more difficult to quantify than simple physical degradation of the resource. It’s called solitude and, unfortunately, its definition seems to be changing.

Solitude, according to the dictionary means:

The quality of being alone or remote from society, implying a condition of being apart from all human beings, or of being cut off by wish or compulsion from one’s usual associates.

This was one of the criteria for wilderness when the government and environmental groups began to inventory public lands in the 1970s. Solitude meant not so much an escape from the human race, as an escape to an unfettered and unmarred natural world. For as long as I can remember, managers of public lands have set limits on the size of hiking groups and attempted, at least, to minimize the impacts from overuse–even from the most well-intentioned. But lately, solitude has come to mean different things to different people. Bikers and hikers come in large groups now, ten, fifteen, as many as twenty, to “explore” the backcountry. They have a limited amount of time and they all want to know, all these thousands of recreationists, where all the “secret places are, where nobody else goes.

Right. There are indeed secret places out there, but not nearly as many as there used to be. The best way to destroy the anonymity of these hidden wonders is to talk about them. And everybody seems to be talking.

Guide Books make good kindling

Guide books are responsible for much of the destruction. Until 20 years ago, guide books were benign, even helpful publications that provided information and advice to tourists about places they already knew existed. We can all use some help finding our way through New York. I’ve used guide books to help me avoid making a fool of myself in Australia. They can be a useful tool and can also be a benefit to small towns like Moab. They can tell you about the offbeat bed & breakfast or the struggling high-quality cafe’. I think they’re great.

But especially in the last 15 years, the proliferation of backcountry guide books and specialty tour guides is changing the face of public lands, diminishing its solitude, and causing ever-increasing resource damage. Often the authors of these books and the leaders of the tours are well-intentioned and love the land and honestly want to share that love with their readers. Others are motivated by factors not nearly so pure. But regardless of motive, the results are often the same.

I first recognized the dangers of tour guides more than 25 years ago. I loved hiking in the Grand Canyon, and even then, the two main trails on the South Rim were beginning to resemble a New York City sidewalk–it even smelled like urine (although in the case of the Canyon, mules were to blame). But the crowds were more than I could endure and I asked a ranger for a solution. He suggested I check out some of the abandoned South Rim trails. Nobody ever uses them, he said; I didn’t even need a permit. But the topo maps still showed some of the old paths and with a little work, I was able to locate the trailheads of the Hermit Trail, the Grandview Trail, and the Hance Trail. The old trails were in disrepair and rock slides had taken out sections over the years, but they were empty and quiet and I loved hiking them. I had not received special treatment–I had simply been imaginative enough to ask for an alternative. I hoped to come back there forever.

But just a couple of years later, on a return trip to the South Rim, I was loitering in a Fred Harvey gift shop when I spied a small booklet among the post cards and picture books. It said:

A GUIDE TO THE PRIMITIVE TRAILS OF THE INNER CANYON

I can still remember that title and the feeling that someone had hit me with 240 volts. I’ve felt it many times since, but that was the first time and I knew that “forever” just didn’t exist. In just sixteen months, hiker use on the old trails had increased so dramatically that a permit system was initiated and the waiting list for the Hermit Trail was a year. A YEAR!

In the years and decades to follow, the primitive trails of the Grand Canyon were on their way to becoming bumper-to-bumper, and although the strictly enforced permit system imposed by the Park Service has helped to ease impacts from overuse, waiting to get a permit can be a lifetime experience.

And since those early guides to primitive areas first made their way to book store shelves, hundreds of others have been whiten for every natural area in America–or what WAS natural.

No guide book writer is as prolific as Michael Kelsey. Over the last 15 years Kelsey has penned numerous guide books for southern Utah and the world. I met Kelsey once near the summit of my favorite mountain in southern Utah. He wasn’t interested in chatting and seemed to be in a hurry on that beautiful June morning and it turned out he was. Kelsey is always in a hurry. I learned that he times his hikes and rarely if ever returns to the same place. His sprints up mountains and down lonely canyons are legendary and he advises his readers to double the times he records in his books.

Kelsey and other writers have opened the doors to hundreds of pristine canyons and valleys and mountain meadows that no one simply thought to visit before–it just didn’t occur to them. And now many of those places are threatened. Several years ago, in Canyonlands National Park, the superintendent actually closed sections of the Needles and Maze districts because impacts caused directly by Kelsey’s books were causing irreparable damage. Here’s what Kelsey had to say about one of those locations:

“The NPS considers this to be a special place because it was left more pristine than any other place. They have never promoted it in any way and will not mention it to you, unless you mention it to them first. They have never put it on any maps either, so few people know about it.”

In the very next sentence, he gives detailed directions. “The rangers will tell you it’s difficult,” he warns, “but it’s not.”

Some environmental groups have repudiated guide books–it has been the policy of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance to publicly oppose backcountry guide books, but others have embraced them and use them.

Today guide books continue to occupy ever-expanding shelf space in regional book stores and show no sign of losing popularity.

Adrenalin Tours

I always thought that no one could come up with an idea that posed a greater threat to backcountry treasures than some of these guide books. But, as always, I underestimated the free enterprise system and the imagination of enviropreneurs. If there is a way to make money off the beauty of the land, someone will think of it. And someone has.

About 45 years ago, Ed Abbey was out in the hot red rocks of the Canyonlands, wandering, as was his habit, and discovered an arch. It wasn’t a huge span, but the setting was incredible..it sat on the rim of a 150 foot canyon and across the gap, the varnished walls climbed another hundred feet. It was as peaceful and serene a spot as he had known. But it was rarely visited by others and became another forgotten place, supremely protected by its own anonymity. Twenty years later, I was hiking in the area and accidentally stumbled upon the same arch, or at least I thought it was. It had the same effect on me. It was so precious that its location became a well-guarded secret. I felt like my own presence was an intrusion and I limited my visits, simply because I often think the best way we can show our love for special places is to leave them alone.

Then one day, I was having coffee with a friend of mine when she began to describe a hike she’d taken the previous day. The more my friend talked, the more familiar the hike sounded. It was the arch and she’d been led to it on a guided tour. She was part of a trial run for a new company that intends to lead hikers to the arch, rappel them into the canyon and return them to their cars–an eight hour hike for about $120. They’ll take up to six hikers per trip which is pretty good money for a day’s work, especially when you consider that the hikers have to provide their own transportation.

Then I learned that another company had been leading the same hike for more than a year. In fact, since 1999, this company, owned by a sometime-BASE jumper and accustomed to a few thrills with his hikes, has led close to 100 tours and as many as 500 people to the arch. There were no trails in that area, but there are now. And at the arch itself, the company leaves its climbing harness tied to a pinion tree. Incredibly, most of the customers are healthy men and women in their 20s and 30s.

The owners of these companies have not been impressed by my concerns. One called me a hypocrite and thinks Ed Abbey would be proud of him for being “adventurous.” A group of Twenty-somethings being led to an arch and a quick rappel for 120 bucks a head. Some adventurers.

Neither of these enviropreneurs sees the danger in taking ever increasing numbers of recreationists into the backcountry. “There’s no evidence that what we’re doing is causing any damage,” one insisted. The damage is already there, but I asked him to consider this: A year ago, there was just one adrenalin tour company leading helpless young jocks to these hidden wonders. And he’s been quite successful. Now another company comes along and, of course, he wants to be just as successful as his competitor.

What could happen next? Eventually yet another enviropreneur will see an opportunity and will establish a third company–all of them going to the same places. And then another. And another.

Some day, maybe sooner than later, these pioneer enviropreneurs will see the increasing damage and decreasing profits from all the copycat competition and they’ll rise up in self-righteous indignation. They’ll be furious. “The place is ruined!” they’ll scream. Their only option will be to find a new place to exploit–one that hasn’t been discovered–yet.

Where does it end?

In the next 50 years, the population of the rural West will increase exponentially, particularly in the New West magnet towns like Moab. We are watching a dramatic change in the way the canyon country of southeast Utah is used. People come to recreate–to hike and bike and to run their rafts and kayaks. They come to challenge the sheer vertical sandstone cliffs with ropes and pitons and carabiners. But enjoying the Great Outdoors is a privilege and carries with it a responsibility. It’s not enough to be an “outdoor enthusiast” or a “recreationist.” We come here to play, but this is not a playground. Many of us make a living, directly or indirectly, from the beauty of this land, but we cannot make a living at the land’s expense.

What happens in the years and decades to come depends upon our own respect and reverence for these canyons and mesas and mountains–or the lack of it.

—Jim Stiles, April 1, 2001

POSTSCRIPT: We all know what happened in the years and decades that followed. Social media. Instagram. Facebook. Tik Tok. Whatever…We watched massive multi-million dollar tourist promotional schemes with no resistance, even from the Greens. The mainstream environmental movement somehow believed that Industrial Recreation was a preferable economic alternative to the extractive industry— they rarely if ever mentioned the impacts of tourism until a couple years ago. In fact, after the publication of the “Mirror” issue in April 2001, Utah environmental organizations broke all ties with The Zephyr and we came to be regarded as an enemy of wilderness, and a “pawn to Big Oil.” The Zephyr Pariah… It was a very strange time.

Now…for Moab at least…there is no going back. Its future has truly been written—in granite. Whether San Juan County and other rural parts of the Southwest learn from the disastrous impacts on other “New West” population centers (I can hardly call them communities), they are doomed to the same fate. I’m not optimistic….JS

For an update on the incredible destruction that is being caused by Industrial Recreation and the alliances (collusion?) between mainstream environmental organizations and the recreation industry (yes, including Patagonia) checkout these Zephyr stories:

Moab Greens Confess: Industrial Tourism Exists! (and now their “solutions”) (click here)

MOAB: Still Doing “Something Physically Impossible (to itself)” (click here)

and for our complete coverage of the Bears Eears National Monument debacle, follow this link to all our contributions to the debate:

How The Zephyr Covered the Bears Ears Debate (click here)

Jim Stiles is the publisher of The Zephyr

To comment on this article, scroll to the bottom of the page. We welcome constructive criticism and new ideas. We won’t tolerate personal, mean-spirited attacks on anyone…JS

Wildlife Need Habitat Off-Limits to Humans!

https://mjvande.info/india3.htm

The Impacts of Mountain Biking on Wildlife and People – A Review of the Literature

https://mjvande.info/scb7.htm

Dude l couldn’t agree with you more and more and even more. Welcome to our Kanab the show that never ends, come one come all until making long lead reservations become as restrictive as living on a reservation itself. Production we need more productive souls tramping and trekking so they to can witness what is and never knowing the loss of what was. Good bye.

Yep, yes, exactly and yeah, ‘we’ all saw it comin’ and, sadly, ‘we’ were also a part of the problem, perhaps only the advance wave. ‘We’ were there when we ‘thought’ canyon country was wide open and empty of humanity’s not-so-humble embrace. But even in the early 80s, I never once had to create a new campsite along a southern Utah dirt track. The campsites were already there. Yeah, I was a part of the problem. But like I say, a member of the advance guard. No jeeping or mountain biking for me. I regarded jeep and bike safaris with horror. The same horror that I regarded the Boy Scouts as a teen discovering the mountains. Who wants to camp out with 30 other people? Apparently, not everybody seeks solitude in wild nature. After 40-years-plus of living “out west”, I realize that the west I loved was always, in part, an illusion. But it was such a lovely illusion and I often think that only the illusion was ever real.

Harsh truth is truth never the less and I suggest that the harsh truth in this prophetic piece will continue to be ignored by those with skin in the game. The selfie of the helmeted freak “getting in touch with nature” was the perfect photo for the end of the article.

Moab, adventureland capital of the southwest, and all it entails is moving south at speed and the only thing stopping it is the San Juan River and the Navajo Reservation Border.

I too am not optimistic.

Social media has done so much damage to natural places by popularizing and letting everybody in the whole world know where these “secret” places are. So much so, that the only thing people do, is go to a now popular place just to wait in line to get a selfie to show that they were there. Just absurd.

I was shocked and saddened when I went through Moab in 2019 after not having been there since 1977. I couldn’t wait to drive on through Moab just to get out of the place. Zion was even worse having to wait 1.5 hours just to get on a damn bus to get in to the park. My wife and I vowed never to go back to Zion unless it was to a

https://betunada.com/2013/03/06/mountain-bike-green-river-the-poor-mans-moab/

Promoting tourism is promoting trash where terrain is clean; tired, tedious predictions of solutude on well trodden paths, and travesty for over taxed counties who are wagering on economic benefits from too many uninfotmed tourists.

I remember reading this 20 yrs ago. Growing up in New England, it was Go West Young Man! I made it to eastern Idaho in 1984 and was so excited. I got into Utah slot canyons before anybody really knew about them. Slots are mainstream now, a Facebook Group for canyoneering came into being about a year ago. There is a FB post every day now. Talk about neat “secret” places being unearthed.

Yes, money corrupts, even when the recipient thinks they have good intentions for that money.

But partisan tribal thinking might corrupt even more. I suggest that the Sierra Club position on illegal immigration had as much to do with politics as with money. Assuming most Sierra Club members and donors are on the political left, they, like many on the political right, were told that they had to accept the entire ideological package. And on the left, that meant defending immigration, legal and illegal.

Decades ago, I described myself to others as a “western states Democrat”. I might have been naive, but I thought values of Democrats in the west (not including the coast) were still more pragmatic and open to smart use of natural resources. Now we have a nation of bizarre cartoon politics, with two parties dominated by their crazy extremes. And I find both disgusting.

I have always thought that the ultimate test for “wilderness” advocates would be the total exclusion of all people, including said advocates. I suspect that most would then admit that they didn’t mean that kind of wilderness.

(Jim, I noticed that in your 2002 piece, you mentioned Saabs. If you had been truly prescient, you would have written Subarus. I suggest that Outbacks(!) and Foresters(!) are nicely symbolic today of the new hypocritical land abusers: people who would never own a Jeep, and are aghast at those who do, but are equally inclined to bounce up some Utah two-track in search of a special camp site.)

Yep, wilderness as biodiversity reserves, where not even the wildlife biologists are allowed in…let’s see if we can get any “environmental” support for that, right? But even better, there’s Loch Wade’s idea, still my favorite all time wilderness piece in the Zephyr:

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2017/08/04/do-we-really-need-wilderness-it-depends-on-your-definition-by-loch-wade/

Thanks, Jim!!

This aggression will not stand, man. The people getting rich off this aren’t just selling real estate or tours. They are selling out a way of life that isn’t even theirs. Consider how places like Espanola or Truchas have kept their towns “their” towns.

This is all about class warfare by the spawn of the Ownership Caste from Kali running working Utah & Arizona out of their own towns in the name of more kicks. It is some of the sickest privilege I’ve seen. Eco-Tourism is just Industrial Recreation virtue signaling with a bigger markup. The state tourism pimps call it “glamping,” “destination tourism” or “the Mighty Five.” What these bastards at Instagram & Facebook have done to the Paria-Vermilion Cliffs-Grand Staircase area is criminal. Just taking one of Zuck’s hands won’t suffice for justice any more. “Get a rope….” The little weasel thinks he’s an environmentalist because he hands out money to other weasels who think they’re environmentalists. I’m sick of luxury SUV crossovers & $3,000 mountain bikes. They create a “servant sector economy” wherever they go, where the cost of housing is Kalifornicated and workers’ wages are in the toilet. The era of Salt River Power & the Bureau of Reclamation is viewed as a lost golden age here. Their workers even received “benefits”…WTF? Local, small business has been bought up by distant capital or driven out by national chains. There’s a new, over-priced brew pub in Page next to the shuttered Windy Mesa…. Now, the Mormon church has even bought back into Big Water (Glen Canyon City). They sold out and left 42 years ago when the town incorporated with Alex Joseph as mayor. They excommunicated members for just talking to him.