AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION:

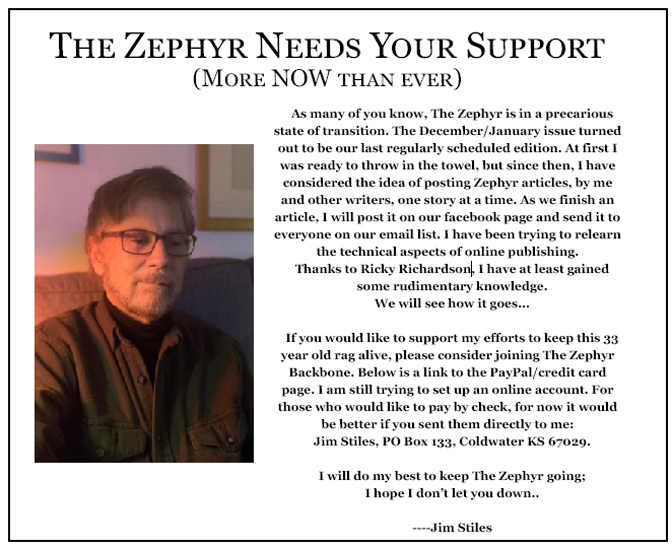

This is an experiment. Throughout my career, I’ve written in the bite-sized chunks of traditional print journalism. Three thousand words was a reporter’s novel. When Jim indicated The Zephyr might halt publication after 30-plus years, I had already started a column on a topic I have avoided for decades: the motorcycle accident that has become a lifelong story arc. I was reluctant to tackle it. I have found each time I dig up a memory for publication, I live with it for a couple of weeks. Most of the time, the process is fairly pleasant; but occasionally, such as with the Doxol fire and other disasters, it is not. The accident is the biggest “not” of my life. I didn’t want to write it, I wanted it to have been written, as the old author’s saying goes.

When Jim gave me the shattering news that The Zephyr might be no more, I decided to complete the piece anyway, making it, without space constraint, “as long as it needed to be,” which proved to be 10,365 words. I couldn’t think of any other publication that would run it, although I joked at the time I was going to send it to a motorcycle magazine as a travel feature.

Jim and I kicked things around. What to do with The Monster, which isn’t, one must admit, truly a Zephyr-type story? Subheads? Done. Break it into thirds to run in consecutive issues? Did that, too. Art? Not much. Then I got chicken a couple of times and recommended against running it at all. My number-one critic and editorial consultant, Kris, had a variety of reactions to the article over the couple of months I wrestled with the thing: First, “I like it,” but “it’s too long” for a Zephyr column, and, weeks later, after a reread, “It’s weird.”

She’s probably right; she usually is.

Now it’s your chance to participate. Options are available: 1. Read it in one chunk. 2. Ignore it in one chunk. 3. Skim it. 4. Break it up into column-sized pieces; I recommend three: 1. Accident. 2. Hospital. 3. Universe, with a beer or gummy break (now that such things are legal over much of the West) between each. Whatever you choose, don’t blame Jim; he’s brave to include The Monster in the new Blue Moon edition during its formative period. And while I might question his editorial judgment, I certainly salute his courage.

And now it’s even longer. . .Bill Davis

********

I am certain Zephyr readers frequently find themselves wondering, “Gee, what’s it like to be hit by a car?” The answer? It’s complicated.

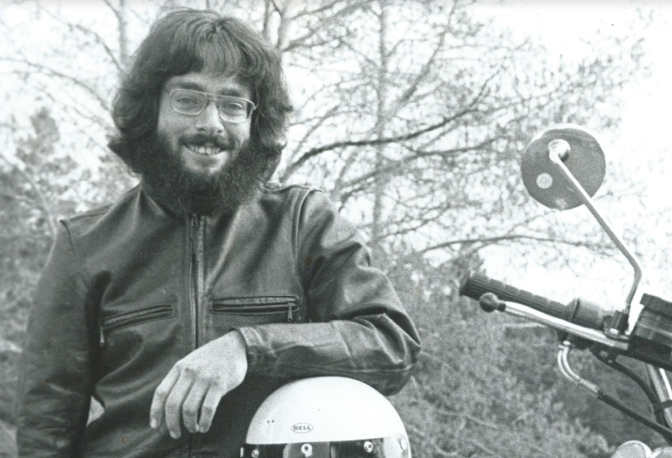

In my opening column, April/May 2020, I mentioned in passing a motorcycle accident that contributed to a less-than-wonderful period of my life following graduation from Utah State University in 1973. The accident had a much more profound impact (so to speak) than indicated in the initial column, generating effects continuing from that day to this, and opening a broader realm of discussion than merely a young man getting splattered at a remote intersection 50 miles southwest of Denver.

Major life changes are sometimes a matter of miles: You decide (or it is decided for you by your high school grade point average) to attend a college far away from your home; you accept a job on the other side of the country, or you fall in love and follow her or him to elsewhere.

Occasionally, however, your life can be forever altered by inches. Take a few minutes now to voyage with me back to Sept. 12, 1975—to Colorado this time, rather than Moab.

It was a day of disaster, choreographed like a ballet; and I’m convinced I was at least partially responsible for the pattern of the dancing. We’ll discuss all that after the scene is set.

Desperate to move out of Denver and get into the mountains, yet still hold on to my job at a mom ‘n pop graphics firm on South Birch St., I had moved into an un-insulated, field mouse-infested summer cabin with inadequate electric baseboard heat, 44 miles southeast of the city up Highway 285 in beautiful Deer Creek Valley.

The commute proved problematic, as, during some months, I spent more on gas, tires and repairs for my 1969 International 4WD pickup than I made at my $155 per week job. Something had to give, and that something turned out to be my good sense.

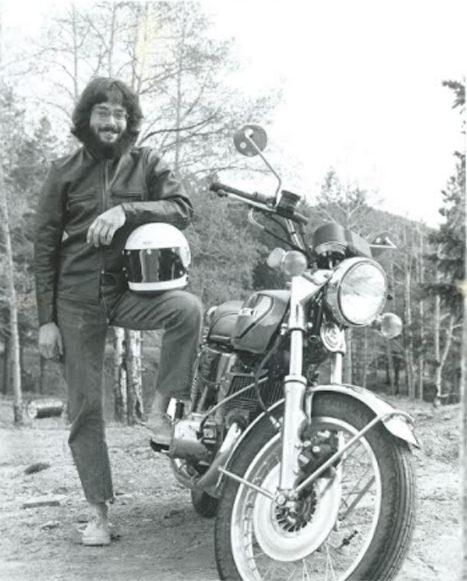

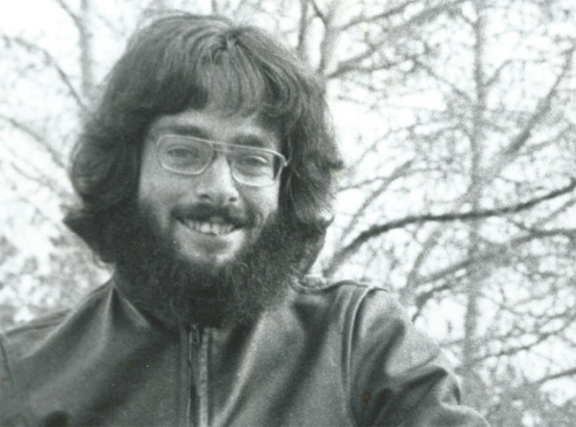

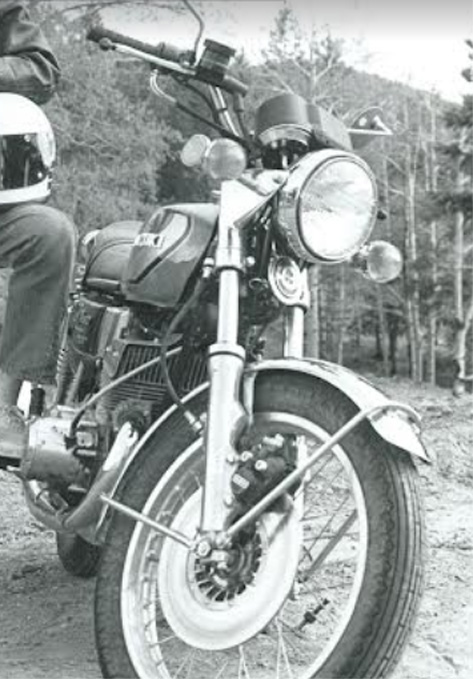

I went to the opposite extreme from a gas hog four-wheel-drive pickup, purchasing a one-year-old Suzuki 550 two-stroke, triple-cylinder motorcycle. The highway cruiser was no lightweight, checking in at 465 pounds, gassed up and ready to go, but still got between 36 and 44 mpg, depending upon how hard it was honked, far better than the 10 or so mpg offered by the large V-8 International on its best day.

“Honking,” in this case, was relative. The engine, which was considered fairly high performance in its day, produced 50 brake horsepower, anemic by today’s standards, when a modern crotch rocket can offer 170 or more horsepower, resulting in that many more ways for the owner to kill him- or herself stylishly, although I confess I’d love to try one on a closed course. There’s a reason, however, emergency room personnel, then and now, call bikes of all descriptions “donorcycles.”

Lacking Joy

I wasn’t a neophyte rider in 1975, as I had owned and ridden bikes for years, riding many thousands of miles throughout high school and college, happily bending them around mountain roads with age-appropriate invincibility. I hadn’t fallen off since my beginning days rat-racing on dirt Forest Service roads in the mountains above Santa Barbara, and had never hit anything solid or vice versa.

Something was different with the 550, however. I never felt totally comfortable on it, and, with the exception of one quick run from Deer Creek to nearby Bailey, never rode it for pleasure; it was just a cheap way to make the hour-long run to work. At the ripe old age of 25, my invulnerability had vanished.

I should have paid more attention to that lack of joy, although it does make a nice lap dissolve into consideration of both the timing and the more metaphysical aspects of the incident, which follows.

The uneasiness intensified on Thursday, Sept. 11, 1975, the day I was supposed to pick up the bike from a Denver Suzuki dealer, where it had been tuned and the oil changed, in preparation for winter storage. Thursday was the last day I had planned to ride before shifting to riding the bus to town, a patently illogical plan (I was young) which would result in my seeing the Deer Creek house in daylight only on the weekends.

Friend Carol, who worked in the same building, offered to run me over after work to pick up the 550. My unease, which had no apparent cause, made me delay the pick-up for one more day, and I took the bus home. With Carol’s help, I did pick up the bike the following day, Friday, the 12th, and headed out of Denver toward the mountains on Highway 285 (a lovely drive, if you ever get the chance to take it.).

As protection against the cold drizzle that developed on the way, I was wearing a rain shell over my down parka, but no gloves. I also wore a full-coverage helmet, which kept my head warm and dry. From the waist down, however, my jeans and running shoes were quickly soaked by the chilly rain.

On the way home, I did something I had never done before; I stopped for a cup of coffee at a convenience store in the tiny community of Conifer, 29 miles from the office and 16 miles from where my final ride came to a halt, a half-mile from my house. Along with the coffee, I also picked up a copy of Playboy (I only read it for the articles), which I shoved under the down parka.

It was a brief stop, and I was soon back on the highway headed west, not noticeably drier than before. After a miserable 12-mile ride, I turned off 285 onto Deer Creek Rd., at the volunteer ambulance station about to figure prominently in my personal timeline. It was at this point that the coffee hit bottom, and my need for a bathroom became acute. With only six miles to go, I pushed for home, turning right from the blacktop of Deer Creek onto the dirt of Hangman’s Rd.

Cute Names

We must pause here for an explanation of the road names in the area. Some developer obviously thought a collection of cute “western” designations would help sell real estate. In the development were (and are) Gunsmoke Drive, Bounty Hunter’s Lane, Silver Garter Road, Tincup Terrace, Bad Bandit, and Stagecoach lanes. I lived, I swear, on Vigilante Avenue, about a mile off the pavement of Deer Creek (That fact becomes important, um, on down the road a piece, during the winter of ’75-’76, as we shall see). All of the development’s roads were dirt at the time; some are paved now. The houses were widely scattered 45 years ago, not so much nowadays. The terrain is fairly level, dotted with pine groves and scattered meadows.

The leaden sky was turning dark as I approached the intersection of Hangman’s and Vigilante. Due to the delay picking up the bike and the stop in Conifer, I would arrive home considerably later than normal. It was here that events took a literal turn toward the strange.

The point of impact was eight feet north of the intersection on the dirt part of Vigilante, just to the right of center. My body ended up in the shallow drainage ditch near the southwest corner of the intersection, where the paved part of Vigilante meets Hangman’s

I was turning cautiously from Hangman’s onto Vigilante—“cautiously,” as one does not toss around a near-500-pound street bike on damp dirt and gravel—downshifting into first gear and slowing to about five miles per hour.

Unbidden, and without apparent cause, my internal voice, the one most of us live with constantly, inhaled sharply and said, “Well, here we go.”

Where the hell, I wondered, did that come from? As I exited the intersection, I looked up Vigilante and saw the car.

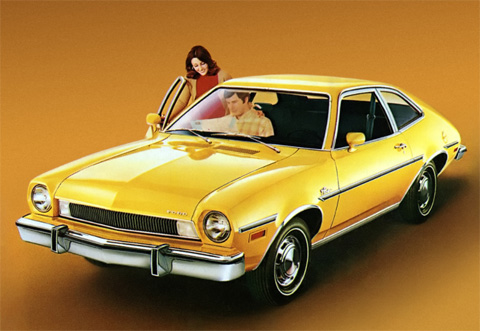

The mustard-yellow Pinto was headed toward me at a high rate of speed, somewhere north of 45 mph, I would guesstimate, way too fast for the dirt surface and the wet conditions. He apparently didn’t know the area, as there was no way he could have stopped before the uncontrolled intersection with Hangman’s Rd. He obviously didn’t know the crossroad was there, and I must have appeared to come from nowhere, screened by trees on the northwest side.

I should point out here that reading about the incident will take considerably longer than the event itself, which lasted no longer than five seconds, beginning to end. I saw the front end of the Pinto dip as the driver slammed on the brakes, rocks spurting from all four wheels as they locked up. As any even marginally competent driver knows, once the wheels lock, all steering control is lost. The car drifted toward my lane.

I was right of center, near the middle of the road, anticipating the driver would release the brakes, regain steering, shoot past me and across the intersection—bad, but better than hitting a motorcycle and rider head-on.

He didn’t.

The car continued to slide into my lane. Unsure what he was going to do, I had come to a near stop, although my feet were still on the pegs. Finally realizing he wasn’t going to do anything but stand on the brake pedal and continue to slide into my lane, I began to angle the near-stationary bike to what would nominally be his side of the road. With the wet dirt, I didn’t dare gun the engine, as the motorcycle’s rear street tire would have spun uselessly. By this time, the Pinto was fully in my lane, and I was broadside to his right front.

Flying Lessons

Without conscious thought, I did something I would have sworn was impossible: I put my right foot down as a pivot and blipped the throttle, breaking the rear end loose and swinging it 180 degrees, as a matador would sweep his cape away from the horns, allowing just enough room for the bull, or Pinto, to pass by with a few inches to spare.

I screwed it up, over-rotating the rear end, perhaps 250 degrees. I was now parallel to the car, facing the same direction. The next memory picture is the sharpest I have experienced in my 71 years: Entering the very edge of my peripheral vision, I saw for a millisecond the yellow front fender. I still thought he was going to miss by inches.

Surprise.

I’m tempted to call it “the impact,” but it wasn’t. It was an explosion, almost indescribably violent; I felt as if my body was being torn in half. I was launched off the bike and into the air, head forward and face down, my arms stretched out like Superman in flight. I was in the air long enough for my internal dialog to finish two complete sentences (Please excuse the language, but I am a journalist, and this is the truth):

“Oh my god, he hit me!” And…

“Boy, are my hips f—-d up.”

The trajectory was flattish, my body never more than four feet off the ground. I flew just under 40 feet, clear across Hangman’s Rd. In the downward arc before landing, my body flipped over so I was flying feet first. I landed on my left hip, the one hit by the car, and slid a few feet into a shallow ditch.

The pain started, and built to a level I had never experienced before. Here is something most accident descriptions don’t include: Broken bones make noise. Each breath was accompanied by grinding and cracking sounds which could be heard from a distance. I was in deep, deep trouble, and far from medical help; the closest hospital, in Denver, was 50 miles away.

In shock, I twice raked my right hand through the mud, chanting, “Oh god, it hurts. Oh, god, it hurts.”

“Stop it,” my internal voice insisted. “You’re acting like an animal.”

I pulled my arm back and lay still. I was having trouble breathing, and was concentrating on getting some air into my lungs when the driver of the Pinto, who looked to be about 17, ran up, also breathless, and produced the single dumbest question I’ve ever been asked.

“Are you okay?”

I responded, and this is a precise quote (Again, please excuse the language—and the grammar—but, you know, journalism):

“Christ, no, I’m hurt bad. Get an ambulance, and for god’s sake tell them to hurry!”

He took off at a run to a house nearby. His useless lump of a passenger, I found out later, never left the car. Still trying to stop the grinding of the broken pieces, I made an effort to move my feet, fearing I might be paralyzed. I couldn’t move from the waist down, but if this was paralysis, why was there so much pain from my ribcage to the upper legs? I knew help would be a long time coming, so I lay my head down, cushioned within the helmet and protected from the rain. I was alone, with time to think.

Wreckage

From where I lay, I had a clear view of the Pinto, which had slid two-thirds of the way across the intersection, a view that was not reassuring. The right front fender was completely crumpled, the hood buckled, and the right front wheel broken off and lying flat under the frame at the aft end of the wheel well. The Suzuki, which had tumbled in a more or less straight line in front of the car, was junk.

“My hip did that.”

It seemed a logical conclusion that this might be my ending point. If I had any internal damage, which seemed likely, I could bleed out from a ruptured spleen or liver long before the ambulance arrived. This thought appeared to trigger something in my brain. Suddenly, I was not seeing the wreckage and the rain, but scenes from my memory, hundreds of them, sliding by incredibly quickly.

“Wow, your life really does flash before your eyes.”

Not my whole life, however; the scenes were all of a kind: pleasant, non-important, but enjoyable events over the span of 25 years. They passed so rapidly I was only to grab hold of one. Years before, visiting home while I was still in college, my sister and I, and mutual friend Linda, spent a pleasant day puttering around Lake Casitas, near Ojai, Calif., in a rented boat. Nothing cosmic, but it had been fun. That’s the sort of memory that flashed through my mind. When the brief show ended, I was left with a major question that seemed to make sense at the time:

“Am I dead?”

Instantly, I found myself, well, my disembodied consciousness anyway, floating about 40 feet in the air, about the height of the surrounding trees, looking down at the still figure in the shallow ditch below. The pain, although still present, was greatly reduced. I regarded my body with what can only be described as mild and transitory regret, as if one had dropped and broken a favorite cup—nothing more.

“It always worked so well, and look what I’ve done to it.”

I continued to drift upward, and found myself looking over the spectacular mountains surrounding the towering height of Mt. Evans, the valley of Deer Creek far below; only now it wasn’t dark and rainy, but clear and sunny, with the cotton-ball clouds typical of the area pulling their shadows over the uneven slopes. I could see clearly in all directions. The view was sharp and clear, and the feeling not at all dreamlike. What I saw is just as firmly imbedded in my memory as the impact and its aftermath.

Over the intervening years, I’ve described a couple of different examples to friends of my mental state during this out-of-body excursion. The first was how an athlete might feel after a tough game, where one had done his or her best, was satisfied, and ready for a rest: “Nice work, kid.” The second is the way one might feel after hiking in a snowstorm, enjoying the quiet and beauty of the scenery, and approaching home, where golden light is spilling from the windows, along with the sound of friends’ laughter, knowing a warm welcome awaits.

One feeling was overwhelming: familiarity.

“I know this place. I’ve been here.”

After what felt like a few minutes of observing the pristine scene, an additional thought arose:

“At least I got to die in a beautiful place.”

Without transition, I slammed back into my body, back to the wet and the overwhelming pain, and the (fairly) certain knowledge I would survive. And I did not want to; I was pissed. Speaking of which, my bladder, which had been an issue even before the accident, felt as if it was about to explode, and I knew I was hours away from relief. I was not happy. At age 25, I had been more than willing to check out permanently, which lets you know just how pleasurable the separation from my body had been.

“I Thought You Were Dead”

When I came to, or returned from my brief near-death experience, or whatever it was, I noted several drivers-by had stopped to offer assistance, some of whom held a tarp over me, trying to keep the rain off. Months later, I ran into one of the witnesses, who apologized for not coming over to check on me, “because I thought you were dead.”

“That’s okay, so did I,” I reassured him.

One of the bystanders was attempting to remove my helmet. Unfortunately, he didn’t realize the only way to remove a snug, full-coverage helmet when one is wearing glasses was to remove the eyewear first, through the small opening in front, before attempting to pull off the helmet. He yanked on the thing, jamming the glasses into my eye sockets. When I fought back, he commented to the other people standing around:

“He’s hallucinating. He thinks he’s still on the motorcycle.”

Hardly. I finally convinced him I was lucid and knew what I was about. In addition, I thought, what was the point in removing my head from a warm, dry, well-padded resting place, only to set it down in the mud at an awkward angle? I finally gave in, however, and sure enough, it was cold, muddy, and uncomfortable.

Shortly after the helmet came off, a Colorado Highway Patrol trooper arrived. From the outset, he was brusque, even complaining he couldn’t find my driver’s license in the proffered wallet. Hoping to die in peace, if that was possibly still on the menu after the certitude of the near-death episode, I finally snatched it from his hands and removed the clearly visible license.

My first impression was correct. I later discovered he had a profound dislike for (fairly) long-haired motorcyclists with beards. Despite producing an exceptionally accurate diagram, which my attorney used to our advantage in a later trial, the trooper blamed me for the accident, writing me up for an illegal left turn a month after the accident, while refusing to charge the driver of the Pinto with anything. Shortly thereafter, approximately a half-hour after the impact, an ambulance arrived. The volunteer service required Emergency Medical Technicians on call to drive from their homes to the station, thence to the scene, resulting in the delay.

In contrast to the trooper, who was positively crabby, the EMTs, two men and a woman, were concerned, friendly, and efficient. After an examination hampered by layers of clothes, one of the men gave me their assessment.

“We think your back and both your legs are broken up high. Try not to move.”

No problem there; I couldn’t have moved had my pants been in flames. Given the darkness, rain, and inability to remove my rain shell, parka, or jeans, the in-the-field diagnosis proved to be surprisingly accurate. The ambulance crew carefully and methodically prepared me for transport, rolling my body onto a backboard, accompanied by loud crunching and grinding from broken bits, causing me to grunt from pain. They finished by strapping me down and using cloth sandbags to keep body parts from moving. As might be expected, the process was excruciating.

The Golden Hour

By the time they had me loaded, an hour had elapsed since the accident—the Golden Hour EMS providers describe as being essential to the most successful treatment of trauma victims—yet I was still at least an hour distant from an emergency room in Denver. During the interminable drive I was fully conscious, although hoping desperately I would pass out.

“If you do, we’ll just have to wake you up again,” one of the EMTs said. There was a high likelihood I was bleeding internally, and losing consciousness would be a sign that things were going south.

During the ride, they cut off my beloved Egyptian cotton rain parka (an amazing garment that was completely waterproof, yet breathed.), although I begged them not to.

“We’ll cut along the seams,” one of the guys said. Liar.

He opened the scissors on the cuff of my down parka.

“Stop!” screamed the other. “You’ll get feathers all over the unit!”

So the down parka, they managed to wrestle off my torso. No one said anything when the copy of Playboy fell out, but it showed up later on top of the pile of clothes in my hospital room. The pile included the remains of my beloved rain parka, which was a total loss, and I could never find another—odd, since it came from REI.

As the crew consisted of EMTs rather than paramedics, they were not able to provide pain-relieving drugs, something in which I had developed a profound interest. During the trip, the female member of the crew held my hand, which I thanked her for, when the crew came to visit while I was in the hospital. The simple human contact meant a great deal, I said, not adding that her being very attractive wasn’t the worst thing that could have happened (She was married, as it turned out).

En route, the crew asked where I wanted to go. I had no idea.

“Whoever has the best orthopedic department,” I responded.

“St. Anthony’s,” all three said in chorus.

So that’s where we went. At the time, the St. Anthony’s Hospital campus was right next to Sloan Lake in Denver; they have since moved west to a much larger facility in Lakewood. After what seemed like forever, we finally arrived.

Here’s a hint for the next time you want immediate service in an emergency room: Arrange to be rolled through the sliding doors on a gurney by three EMTs shouting, “Motorcycle accident!”

You’ll be amazed how many people in scrubs materialize to run along with the stretcher. Be warned, however, the price you pay for that attention is high. And yes, the ceiling lights in the hallway really do whip by as intense faces look down, just like every hospital movie you’ve ever seen. And yes, you really do think about things like that, even when you’re busted up and very, very concerned about your future.

Levitating

At this point, things began to get a bit hazy, as shock settled in.

“Okay,” I thought. “I’ve maintained to this point; now you guys handle it.”

A nurse began to cut my jeans off. As she did so, gravel and mud that had been jammed under my pants by the impact cascaded out on the gurney and floor. She drew back involuntarily.

“Ewww!”

“Hey, lady, I didn’t do it deliberately,” I thought, but didn’t say. The mess did seem incongruous in the sterile examination room.

A surgeon appeared and bent over the gurney, gently feeling my pelvis.

“How long has it been since the accident?” he asked the ambulance crew.

“Two hours.”

Without a word, he whirled around and leaned on a chunk of my pelvis that was popped up above the rest, cut off from a blood supply. The large piece of bone dropped about two inches. I screamed and levitated.

“That will be the low point in our relationship,” he said. “I won’t have to do that again.”

“Good,” I gasped. “Sorry about the sound effects.”

This became the baseline for my interpretation of the universal 10-point pain scale using the happy-face to crying-face emojs one sees in every hospital room nowadays. Starting the evening of the accident and continuing to the present, to me, stage 7 is when conversation became difficult. At stage 8, only short, gasping phrases are possible. When you hit 9, you can choke down the screaming only long enough to manage a single-syllable word. If 10 arrives, the screaming becomes involuntary. Anything above that: You pass out.

This was a 10.

I learned a valuable lesson that night: Pain is actually as open-ended as the Richter Scale. Whatever pain you are experiencing, it can get worse; there is no limit. It has given me a lifelong appreciation of, and sympathy for, victims of torture, soldiers surviving explosions with traumatic amputations, and burn victims undergoing debridement, which, I have heard, is horrible. In a multi-decade attempt to control severe lower back pain from that day to this, I have spent countless hours in pain clinics and orthopedic surgeons’ offices, occasionally overhearing conversations like the following:

“Oh, doctor, this is the worst pain I’ve ever experienced. It’s definitely a 10!”—frequently followed by a request for pain meds.

Sport, if you are capable of speaking in complete sentences, it ain’t a 10. I later obtained the surgeon’s intake notes from the night of the accident, for a lawsuit I filed against the kid who hit me.

“The body is that of a pleasant young man in his mid-20s, in moderate distress,” the doctor had written.

“Moderate”? Buddy, you give me a baseball bat, and I’ll show you “moderate distress.”

It made me wonder how he defined a 10. I also have no idea where the “pleasant” came from. One of the ambulance crew members mentioned to the ER staff that I had an extreme need to urinate prior to the accident; by this time, that was a serious understatement. The EMTs had advised me to pee in my pants during the ride down, but I hadn’t been able to.

A nurse (to whom I hadn’t even been introduced) grabbed hold of a 25-year-old male’s favorite body part and proceeded to thread a 27-foot-long eight-inch wide plastic tube wrapped in barbed wire up to my tonsils (Well. . .). I screamed and levitated again, a little lower this time. Barbed wire or no, the instant relief was the most profound I have ever felt. Finally, about three hours after I got hit, I watched a syringeful of golden liquid flow into the IV line—morphine (or more likely, one of the synthetic opiates; I wasn’t fussy). This was my first experience with a narcotic. I quickly learned the pain relief was not absolute; it just put the pain into the next room, and made the patient so dopey he couldn’t complain.

The next stop was X-ray. After the care of stabilization demonstrated by the EMTs, the X-ray visit was an eye-opener: The technician rolled my body around like a sack of potatoes, generating loud grinding noises that were truly impressive. I was doped up enough I didn’t really care. The surgeon met me when I was rolled back to the examining room, and told me exactly what I needed to hear:

“It’s your pelvis, not your back. You’ll walk again.”

Make a Wish

“You’ll walk again” may not be the equal of “I love you,” in importance, but it ranks right up there with “The growth is benign,” and “We find the defendant not guilty,” a phrase which also turns up later in this little adventure.

Over the 17 days I was in the hospital, I picked up some more detailed information on what had apparently happened during the accident. When the car hit my left hip, for milliseconds, the leg was trapped between the fender and the bike. The motorcycle was kicked violently sideways, forcing my legs farther apart than design parameters permitted—a “make a wish” break.

Both iliac rings were fractured top and bottom in multiple places. In addition, as the pelvis is a circular structure (when viewed from above), something had to give on the back side, and that something was both sides of my sacrum, vertically, along both rows of holes through which lower body blood vessels and nerves pass.

Depending upon how one counts (i.e. Does a free-floating chunk of bone count as one or two? It’s a problem.), somewhere around eight or nine fractures were bobbing around. The surgeon called it a “shattered pelvis,” and that was good enough for me. At the time, not much could be done medically for multiple pelvic fractures; putting a cast on bones underlain by squishy internal organs was useless, as the pieces could not be held in place.

Back in the emergency room, while the painkiller was blessedly kicking in, the doctor grabbed the wall phone.

“Get me an operating room and two surgeons. If this kid is bleeding, we’re going to have to crack him right now.”

Actually, I was surprised I wasn’t on the way to an operating room already. Weren’t they going to screw things back together? As it turned out, no. However, an E.R. nurse explained that the sharp pieces of a fractured pelvis inevitably cut something underneath, frequently requiring immediate surgery. In my case, my much-abused bladder had been lacerated, but not ruptured—fortunately—and the liver had a contusion. Had anything essential ruptured, I never would have made it to the hospital: Lucky. Fortunately, the bleeding stopped the following day.

Approximately an hour after I arrived, they shipped me upstairs to the orthopedic floor. An attendant left me in front of the nurses’ station, still on the E.R.’s gurney. A few minutes later, a nurse leaned over the countertop and looked at me closely.

“Hey,” she announced, “someone get a doctor. This guy is bleeding all over the gurney!”

Bleeding? Here I had been congratulating myself —even though stoned out of my mind—on having the good taste to confine all my injuries internally, where they wouldn’t upset bystanders, or the patient, if I’m honest. Also, I had just come from the E.R. Wasn’t someone down there supposed to notice such things?

They flagged down some poor resident who was on his way to the cafeteria, and brought him a suture kit. Somewhere during the accident, a sharp part of the bike or car had cut a gash into my leg just below the inside of my right knee. I had been suffering from exposure so severe no one in the emergency room noticed the opening, which didn’t start bleeding until three hours after the incident, when I finally warmed up. The doc, who visited me in my room the next day, said he could have stuck all four fingers into the cut up to the first knuckle. I’m glad I never saw it in its raw state. As the edges were too ragged to bring together, he folded them under, then put in five gigantic, Frankenstein-variety X-shaped stitches and a rubber drain, right there in the hallway. He didn’t use any numbing agent, as he apparently figured I was plenty doped up. I wanted to tell him it hurt, but couldn’t talk.

This was yet another lesson for me in modern medical science: Just because you can’t speak doesn’t mean things don’t hurt; it does make for a quiet ward, however, which was possibly the goal.

Replay

For about a week, I encountered a phenomenon several acquaintances over the years have said they have also suffered after a trauma: endless repetition of the incident. A mental videotape of the accident ran through my mind continuously for days, until I wondered if I were going nuts. I wasn’t, and you’re not, any of my readers who have experienced something similar; it is apparently fairly commonplace, and will ease over time.

A couple of days after I had been admitted, a group of about six nursing students came in to change the bed, although they hadn’t yet been trained in the technique. How hard could it be? Three stood on each side, rolled up the edges of the sheet to lift it like a hammock. I tried to ease the load by lifting as much of my body weight on the metal triangle hanging from a frame over my head: big mistake on all our parts.

As they lifted, my fractured pelvis folded in so my hips were facing each other, which I wouldn’t have imagined possible in my worst nightmare. I screamed and again levitated as I had in the E.R., which scared the students, so they dropped me. An R.N. who was out in the hall investigated the noise, and, expressing considerable disgust, showed us how it was done: lengthwise, a side at a time, sliding the patient out of the way. I offer this in case my readers ever face a similar challenge.

The rest of my 17-day stay was peaceful, albeit boring. I simply held still and healed. The only treatment I received was a half-hour of physical therapy, which consisted of learning how to navigate stairs using crutches. That was it. The long days were interrupted only by meals, and a few visitors, including Carlotta, one of my coworkers at the graphics firm, a lovely, but overly sensitive soul. During her first visit, the crunching and grinding of bones as I breathed (which finally stopped after about a week, and I promise not to mention again) made her so ill she had to leave. Shortly before I was discharged, she happened to visit right when I had pulled myself upright and balanced in a standing position for the first time—Ta da!

It was a real moral victory: I was vertical, although I couldn’t move my legs. I was so wasted-looking, however, that Carlotta burst into tears and ran from the room: sensitive, as I said. We didn’t see each other again until I went back to work, a month after the accident.

I was finally released during the first week of October, and hitched a ride home with a friend who lived in the area. Jimmy and Michelle, my roommates, who had planned to move closer to town around the time I got hit, stuck around for a week to help me settle back in and adjust to life on crutches. One of the biggest challenges turned out to be getting into bed, a mattress on the floor, each evening. I would lay the armpit end of the crutches on a nearby chair, and use them as a ramp to slide down between the sheets. Getting out of bed was considerably more difficult.

When the week was over, I simply had to go back to work, as I had no money. I established a new routine: I rose (slowly) around 5 a.m., then crutched my way one mile down to the pavement on Deer Creek (passing the site of the accident at the halfway point), where I hitched a ride to the nearest stop for the Denver bus, an eight-mile jaunt. A lengthy bus ride down to the city, a transfer to a city bus, a third-of-a-mile of crutching, and I was on the job at the graphics firm, after which I would spend eight hours in the darkroom. Reverse the trip, and I was home sometime around 7 p.m.

Creative Crutching

The weather turned cold while I was still on crutches, altering the schedule from a challenge to an expedition. It snowed early that year, and my house was right on the 10,000-foot line of the topographic map I had on the bedroom wall, so the snow and ice stayed as the temperature dropped.

I am here to tell you that crutching a mile in the dark on a snow- and ice-covered dirt road is an ironclad bitch, especially when you are trying desperately to avoid falling and breaking recently healed bones. I distinctly remember pausing one November morning halfway down Hangman’s Rd. to catch my breath.

It was 10 degrees below zero, and I was bundled up in all my winter gear, including the down parka the EMT hadn’t cut off in the ambulance, with the hood cinched down so only my iced-over glasses were exposed.

“Well, kid, this is about as rough as it gets,” I thought (especially since the woman I had lived with for five years left me heartbroken six months before). If you don’t feel depressed and suicidal now, you never will.”

I didn’t. In fact, I marveled as always at the snowy beauty of Deer Creek Valley, rimmed by the looming peaks of the Rockies and Mt. Evans, with the first hints of pink morning light painting the sky to the east. I knew I was getting better, and that my own decisions had resulted in the accident, even though I hadn’t caused it.

The healing, however, was proceeding slowly. The nerve damage in my legs was so severe, even two months after the accident, when I was sitting in a chair, I could not lift my feet from the floor. This presented a challenge at work, as part of my job included picking up bundles of newspapers at the printing plant and delivering them to our Denver customers. As I was at the time vehicle-deficient for obvious reasons, I had to use my boss’s Mustang, which had a stick shift.

I never explained the specifics to him, but I drove around Denver for a couple of months lifting my feet onto the pedals with my hands and pushing down on my knees every time I had to shift or stop; the steering kind of took care of itself. Amazingly, I never hit anything. I also learned to carry a bundle of papers on each crutch, hooking my fingers through the wrapping strings below the handhold. Not surprisingly, with all this driving, crutching, and carrying, the quick discharge from the hospital and the lack of aftercare, my pelvis healed in a distinctly crooked fashion, with the left leg about two inches shorter than the right.

Shortly after the end of my Crutch Period, I had to deal with the legalities of the accident: As the highway patrol trooper had blamed me, and written me up for an illegal left turn, while failing to charge the Pinto driver with anything, I wouldn’t be able to collect from the kid’s insurance unless I proved my innocence. In addition, I was stubborn, and refused to accept responsibility for something that had so clearly been the other guy’s fault.

Trial by Jury

My attorney (wisely, as it turned out) recommended a jury trial. The entire experience was surreal, right out of a TV courtroom drama. It was appropriate the drama played itself out in the Park County seat of Fairplay.

The trial took all day, from jury selection through deliberations, not ending until after dark. While awaiting the jury’s decision, the judge, prosecutor, my defense attorney and I shared a bowl of peanuts, oddly convivial after a contentious day. While we munched, the judge commented that a majority of recent disputed traffic cases appearing before him had involved the trooper who handled my accident. The cop, the judge said, seemed to have a habit of drawing the wrong conclusions.

I was concerned the jurors might be cranky after wasting 10 hours on such a minor charge, involving a bearded motorcyclist yet, but the result rejuvenated my faith in the jury system. They grow good people out there in the mountains.

As they walked in after concluding their deliberations, one of the jurors, a grizzled old rancher clad in worn jeans, denim shirt, cowboy hat and boots, caught my eye and winked. I knew I had won before the clerk read the verdict.

Nearly a year later, the Pinto driver’s insurance settled out of court minutes before the civil suit I had filed against him was scheduled to begin in Golden. The kid’s attorney also agreed to drop the countersuit for the damage my hip had done to his car. Gee, thanks. We settled for a measly $10,000, of which my attorney got half. For some reason, ever since the original incident I have had an unreasoning hatred of Pintos, more so, bizarrely, than my dislike of the driver who had caused the whole mess.

My real annoyance was reserved for the lump of a passenger in the car, who had never exited the vehicle to get help, or even check if their victim was still breathing. My attorney, who hoped the teenager might be a useful witness in the suit, had located him in Canada. We dropped the idea when he claimed I had come through the intersection at over 50 mph. You bet—on a 500-pound street bike, on dirt, in the rain, in first gear.

Fortunately, a few months after the collision, things healed up, and I returned to most of my familiar activities, with a few exceptions. I gave up downhill skiing after one of my friends commented on my first attempt in late December, “You’re skiing like an old lady.” He was right; I didn’t fall all day.

Backpacking also went out the window after my first post-accident trip; I couldn’t stand hiking with the hip belt fastened, as the pain was too intense, and you really couldn’t use a packframe without the belt. I did, however, return happily to day hiking. As might be expected, riding motorcycles was out. I had decided I would never be injured or killed in a motorcycle accident, and there was only one way that could be ensured. “Never again,” I decided, although there was one exception during my tenure as news editor of The Times.

My college roommate dropped by for a visit one day, with two kayaks in his van. We decided to run the Daily section on the Colorado River, launching just above New Rapid in Professor Valley and finishing up below White Ranch. After we pulled out below White’s, Ned hitched a ride back up to his van, while I kept an eye on the boats in a dirt pullout along Highway 128. As I waited, friend Bob Lowrey, who had been both a Grand County deputy and Moab City Police officer, passed by on his new Kawasaki KZ1000 (one of those road bikes with the really wide, air-cooled transverse four-cylinder engines one doesn’t see anymore). At the time, it was one of the fastest motorcycles on the market, the first mass-produced bike to have fuel injection. With 90 horsepower and weighing 565 pounds with fluids, the KZ was considerably more powerful and heavier than my destroyed Suzuki. He was accompanied by his then-girlfriend, who I also fancied a bit.

Bob was well-aware of my aversion to bikes, and the reason for it, as we had traded life histories during a lengthy ride-along to the Book Cliffs one day. He pulled over to say hi, and, with a bit of a smirk, asked if I wanted to take the Kawasaki for a spin, knowing what the answer would be.

Guys will do silly things when an attractive woman is around.

“Sure,” I said. He cocked his head to the side and gave me a questioning look as the two of them climbed off.

Back in the Saddle

I got aboard, sans helmet, revved the engine and dumped the clutch, gunning it just enough to step the rear wheel to the side, spraying dirt and making the rubber chirp when I hit the pavement. I’ll show you, smart guy.

I took the engine to its 8,000 rpm redline and ran through three gears leaning hard around a half-dozen corners. I turned around and came back in the same fashion, hitting the rear brake just hard enough to kick the rear wheel out to the side again as I slid to a stop in the dirt.

“Nice bike,” I said, feigning casualness, as I handed over the KZ, strolled over to a rock, sat down, and took out my cigarettes (I hadn’t yet quit). Bob looked at me oddly again as the two of them mounted up and roared off.

I took out my lighter while they disappeared up the river road, but my hands were shaking so badly I couldn’t hold it to the end of the cigarette and had to give up. The body remembers. I was so rattled I have never again thrown my leg over a motorcycle—nor will I.

I lived with a crooked pelvis for 34 years, with the misshapen structure applying pressure on my lower back. The resulting pain was continuous, varying in intensity from 3 to 7 on my personal scale. Most of the time, I could get some relief by lying down for 20 minutes. This carried me through 18 months playing in a rock band, six-and-a-half years as news editor of the Times-Independent, and two years in graduate school.

Once I started my career as a community college professor, however, with decent insurance and income, I tried to find permanent relief. That effort lasted for the next two decades, without success. I tried everything: shots, surgery, having an electronic stimulator, physical therapy; you name it. I also during that period had extensive experience with opiate pain pills, both organic and synthetic. I don’t, by the way, recommend them for extended use; they lose their effectiveness, and you still end up addicted, even when the drugs are legal and prescribed. One can get off them, as I eventually did, but it’s not a pleasant experience.

The last couple of years of my teaching career, the pain was getting out of hand. It got to the point where I couldn’t walk more than 100 yards without stopping to hold onto something or sit down while I caught my breath. At work, I had to stop a couple of times between the parking lot and my office, which was intolerable for someone who loved outdoor activities.

In 2008, a friend mentioned an orthopedic surgeon in Santa Monica she had heard about, who was developing a procedure where crooked pelvises like mine could be straightened by surgery. The operation was involved, lasting from 10 to 12 hours, followed by 10 weeks in bed holding as still as possible.

It took about a year to make the arrangements, including scheduling the procedure for early June, which would give me the summer to recuperate, nursed by my wife Kris, before returning to the classroom in August. The surgeon explained that the results would not be ideal. The back pain would remain, but I would again be able to walk several miles, rather than 300 feet at a time. It was a compromise I was willing to make: I could live with the pain, as long as I could hike again. As arranged, we flew from Sacramento (the nearest airport) to LAX in early June of 2009. On the assigned date, Kris was the first person in the waiting room at 5 a.m., and the last to leave 12 hours later, when I was finally in recovery.

Broken Again

Simplified, the operation involved re-breaking the pelvis, rearranging the pieces, then bolting and screwing things back together as close to the original configuration as possible. The procedure was rarely done, and about as major as orthopedic surgery gets.

I told family and friends the hardest part of the operation was finding and sterilizing a 1975 Ford Pinto.

Actually, as one might expect, the repair was a good deal more sophisticated than smacking the body with a car. The patient was placed onto a table that could be flipped over for access to both the front and rear. The pelvis was secured to the table with bolts screwed through vertical tabs and into the bone just above the hips on each side. Two additional bolts were screwed into the femur of the right leg, just above the knee. Cables were attached to the bolts, which ran to a winch, used to pull the leg, moving pieces of the pelvis back into place after the old fracture lines had been cut with a bone saw.

The front of the pelvis was opened first, the bone cut and rearranged, then the incision closed temporarily. The table was then flipped, and the back of the pelvis opened. Vertical cuts were made (with great care) through the bone along the holes of the sacrum, through which the nerves and blood vessels to the lower body pass.

The pieces were secured in place with a stainless steel plate screwed into the bone and a 9 ½-inch lag bolt inserted from one side of the pelvis to the other. After the rear incisions were closed, the table was again flipped and the front reopened. The winch was again used to make final adjustments, then two more plates installed at the top of each iliac ring, with 11 screws reaching across the gaps to secure the lower iliac rings, all of which had been cut with the saw.

Something over 160 staples were used to close all the bolt holes and incisions. Six months later, the lag bolt and rear plate were removed, but the front plates and screws remain. After 10 weeks immobile, I went back to work while spending a month in a wheelchair and another month on crutches. I really hate crutches.

When combined with the later replacement of my right hip and shoulder, I’m surprised TSA alarms don’t start going off when I walk into an airport terminal building. I do get the stink eye every time I pass through a security detector.

Ultimately, the surgeon proved to be as good as his word: I walk two miles a day with the dog now, could easily do five, and could probably make 10 to 12 if I had to. Also, as per the doc, the pain remains, usually at the 3-4 level, until I bend over, sit down, or stand up—which causes a momentary spike to 7 or so. I’m not complaining. One word describes my overall feeling about the whole experience:

Gratitude.

Gratitude that things weren’t much worse. I could easily have died, ended up in a wheelchair, or worse, bedbound for life. As I said in the opening, this is a tale of inches, and many people have gone through ordeals that were much worse, where the inches didn’t break in their direction. I’ll save any sympathy aimed my way for them.

Analysis

But the story does raise broader questions. There are, basically, two possibilities for life after death:

1. There is.

2. There isn’t.

My accident and its aftermath feature elements of each. The out-of-body experience didn’t include meeting any religious figures or welcoming dead relatives frequently associated with near-death events; in fact, it didn’t include people at all, but it did involve seeing my body (and not being particularly concerned), and witnessing the incredible beauty surrounding me in bright sunlight, rather than the dark and rain I knew were present. In addition, I was flying, which was neat.

Yet the experience felt as real as everything else associated with getting hit by a car: the impact, lying in the ditch, the ambulance ride to the hospital. Also, the overwhelming feeling of familiarity was real. “I know this place.”

Some researchers have postulated that near-death experiences are physiological, the result of a severe injury, followed by a massive influx of adrenaline and endorphins. If so, it’s an evolutionary development

that is both useful and calming.

On the other side of the coin is the 12-hour operation, and the anesthesia associated with it. If you’ve never been anesthetized, it’s an interesting experience. I clearly remember being wheeled into the operating suite, a shot, and the gas mask being placed over my face. There was no counting backward from 100 or any of that. It was like flicking a light switch; I was on, then off.

I’ve described much of what went on during the operation, some of it pretty seriously ugly; I’m glad I wasn’t there. I remember nothing—zip. It was oblivion: no dreams, no half-remembered sights or sounds, no awareness of the passage of time. To me, those 12 hours never existed and never will. Extend that by whatever time you wish, and it could be the oblivion of death, which many philosophers have described as a condition we cannot imagine. To imagine oblivion, you must have an observer, and, in the case of death, you don’t. To many non-religious or non-spiritual folk, that is what is in the wings when life’s play closes. In an odd, way, I guess I got a taste of it, or, at least, as much of a taste as a living person can ever get of being dead.

I am not, nor have ever been, religious. I was not raised in a church, was never baptized, and am not a believer in any organized (or disorganized) religion. I simply have never found a church-based belief system I can accept. Yet, while agnostic, (what Kris calls “waiting to find out”) I lean fairly heavily toward number one listed above, because of events surrounding the accident—the “if onlys.”

If only I hadn’t delayed picking up the bike by a day; if only I had left work earlier, or later; if only I had ridden faster or slower—10 seconds would have done it; if only I hadn’t stopped for coffee in Conifer—the first time I had ever done so; if only that idiot kid knew how to drive; if only I hadn’t spun the Suzuki around quite so far.

If only I hadn’t bought that damned motorcycle.

The coincidences necessary to bring me to the point of impact at that precise second strain credibility. And to me, the biggest mystery of all was: Why had my inner voice said, “Well, here we go,” with a sharp intake of breath, seconds before I had seen the car, or known I was in trouble? That memory remains as sharp and clear as any from that evening. It sounded to me then, and does now, as if a plan had been in place, and at least part of me knew what it was. The thought has followed me for 47 years.

If the whole thing was a life lesson, though, it seems a bit harsh. By age 25, I had already decided kindness was the way to go, and caring for other beings, both human and non-human, was part of my belief structure. Yet the feeling—the strong feeling—I had, and have, is that the event was not forced upon me. For some as-yet-unfathomable reason, I seem to have been at least partially involved in the arrangement.

The (Really) Big Picture

I’ve always been of a scientific bent, having been educated in that direction, but have always felt there might be some “looseness” to existence. This is especially true when you get down to the quantum level, where giggly things take place, such as a particle being in more than one place at a given time, or binding between particles continuing, no matter how far apart they are. Given all that, a non-physical afterlife for us doesn’t sound all that weird.

However, if science is correct (and I think it is), and the universe (visible and non-visible) is anywhere from 94 billion to seven trillion light years across (depending upon the model), containing somewhere around 200 billion trillion stars (and that’s a very rough estimate), I simply cannot believe in an all-powerful being whose only concern is one tiny planet near the outer edge of a typical galaxy. In a universe that big, I suspect there’s room for all of us, religious and non-religious alike. One suggestion I find appealing is that the universe is a self-aware entity, split into near-infinite parts, of which we are infinitesimal, but important (to ourselves, anyway), fragments. These fragments, individually, would make up what we call souls, and together, the godhead. It’s something to think about, anyway.

Feel free to disagree, of course; I certainly don’t have The Answer, and I do find much that is valuable in the religions I’ve encountered over the years. Over what is becoming a fairly long life, however, I have noticed two items upon which I think we can all agree. How’s that for a claim?

1. It seems to be hardwired into the system that each of us will encounter pain during our experience, and here, I don’t mean the minor stuff: “He didn’t ask me to the prom,” or “It’s tragic I can’t find another one of those Egyptian cotton REI rain shells they cut off me in the ambulance.” I mean the soul-searing sorrow and depth of black despair that come with events such as the sudden death of a loved one, watching someone essential to your life depart, never to be seen again, suffering a severe illness or injury: any sort of emotional or physical impact that makes you wonder how your existence can continue.

I’ve heard this described as “Everyone is mourning someone.” Count on it; if this hasn’t happened to you yet, it, will. Again, it appears to be built into the system, no matter how much we wish it wasn’t.

It would be nice if we could say:

“I appreciate the offer, but I think I’ll skip the part where my psyche is shattered, and I must completely rebuild my life. Thanks, anyway.” We are not allowed to do that; at least, no one I have known has. The second point, however, is the opposite:

2. We have absolute, total, and complete freedom in one area, which also appears to be part of the system.

It’s how we treat one another. If you really wanted to, and had the necessary drive, you could devote your entire life to being an asshole to everyone you encounter. I don’t recommend it, but you could. You could be nasty to family members, insulting to co-workers, and drive away anyone who tried to get close to you. That’s freedom—of a sort. I’ve met a few people like that, not many, but a few. Well, maybe two or three, and in answer to your question: none of your business.

Walking Each Other Home

Conversely, you could devote your life entirely to helping others, lifting them up, being constantly available to assist where needed, while ignoring your own needs. I’m not sure I’ve ever met anyone that all-fired devoted to doing good, but I’ve known a several people who come awfully close.

Most of us, I suspect, fall somewhere in the middle. Wherever we are on the continuum, we made a conscious decision to be there. This decision just might be the reason for our existence, if there is one.

A quote from Ram Dass summarizes what I think is a good, and practical, attitude toward life:

“We’re all just walking each other home.”

He assumes our existence continues after death. In addition, he says, we should help each other along the way. My interpretation is that when someone needs help, perhaps during one of those unavoidable No. 1 experiences, we should offer a shoulder, or, when offered assistance, accept it gracefully. We should offer assistance not to gain a reward, or avoid punishment in this life or what follows, but because it is the right thing to do. In addition, such assistance makes both the person offering help, and the one receiving it feel better, and brings us closer.

An additional point is reflected in that ancient cliché I experienced: “My life flashed before my eyes.” Well, no, not the whole thing, just hundreds of perhaps inconsequential, but enjoyable, memories—pleasant things. It seems only logical to make more of those. Having started my eighth decade on earth fairly recently, it is obvious the ending is now much closer than the beginning; I can read actuarial charts.

I’m not in any rush, though; the older I get, the more I savor each day, but as the years, dings and dents accumulate, death is looking less like a big, scary, featureless void, and more like a finish line. If, as I suspect, there is something after our bodies (so to speak) give up the ghost, new adventures await. However, if it is oblivion, we will never know.

In either event, at least our backs won’t hurt.

Afterword, the first: Some readers may remember Bob Lowrey as Robin. Bob died Aug. 11, 2016, in Logan, Utah, at age 62, way too soon. My condolences to his family and friends.

Afterword, the second: Before anyone yells about the universe being only 14 billion light-years across, which is what we can see from Earth, some recent info: When an astronomer looks as far away as possible, of necessity he or she is looking into the past, as well; we are never seeing the universe as it is. Several scientific teams have used a variety of data to attempt an estimate of the current size of the cosmos, allowing for expansion to the present. Most estimates describe a sphere approximately 92 billion light-years in diameter, given a constant rate of expansion. However, a University of Oxford team, allowing for differential expansion rates, recently came to the conclusion that the size of the universe is about 250 times larger than previous estimates, hence the seven-billion-light-year conclusion.

Here’s a link to an article on Space.com:

https://www.space.com/24073-how-big-is-the-universe.html. A safe assumption: No one knows for sure, but it’s real, real big.

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

TO COMMENT on this story, please scroll to the bottom of the page.

.

Bill Davis,

Thank you for sharing this story. I have been restoring two neat Triumph motorcycles given to me by my father’s friend. I am enjoying the restoration however, I have been wrestling with the decision of how involved I want to get in riding them. You provided the answer, loud and clear. Thank you for helping me with this. I’ve had enough enjoyable motocycle riding, dirt and street, in my life. Time to call it quits…. Peace to you Sir.

A gripping story! This is just one reason why the Zephyr needs to conyinue. I’ve only been on a motercycle once, as a passenger and thanks to my Father I was terrified for the whole 7 mile ride. My Dad was a pathologist who did autpsies of all kinds. I remeber a dinner conversation when I was a teenager and contemplating a motercycle. Wisconsin had just passed a law requiring helmets. Over a plate of food that I was devouering with abandon, as teenagers do, he said that he was glad the law had passed. Now he had a container from which he could scrape out the brains and what was left of the victoms head. The plate of food went unfinished….

Great read. Thanks Bill.

espesh liked the O-of-B bit. i sus/ex-pect you, too — recall the Ernest Hemingway bit of the same thing. neat that you came a little bit close to describing Ꝏ all due to a few seconds of pure heck.

Hey Bill, I have never met you as far as I know but I related very well to your story and especially the part about your out of body experience and your musings about life after death. Discussing “life after” with an atheist friend years ago when I lived in Pullman, Washington he said, “I think we are both in for a surprise when he die”. That is true for me I am sure but if he is correct we simply vanish and no awareness will continue.

I found your writing fun to read and your ability to describe events, especially pain, excellent. I recently enjoyed nearly two weeks in a hospital as a result of pain at about a 7 that made me finally listen to my wife and agree to take an ambulance ride to the local hospital. While in the hospital a good friend named Jim Stiles appeared at my bed side. That visit made me more determined to recover.

My Dad broke some bones on his motorcycle and discouraged me from ever owning or riding on a motorcycle.

You are correct. After 10 one mercifully passes out.

Thanks Bill and Jim too. So many parts of the story resonate for me, both personally and professionally (retired NPS Ranger). The most meaningful to share with all is the time when doing CPR on a young girl who had stopped breathing for a while, I felt a presence hovering above me watching. Eventually Iwas able to revive her and assist her breathing while waiting about an hour for an ambulance to arrive in the mountains outside Boulder CO. I felt that same presence a day or so later outside her hospital room when I went to see her. All this because I “happened” to meet some people in a campground pool in New Mexico while on a cross country trip and spontaneously altered my plans quite a bit to go climbing with them in the Boulder area a couple of weeks later.

Thanks Ed…I was involved in several CPR situations at Arches, but they were all very old and I was never successful in bringing someone back. That must be an amazing feeling to have been able to restore her life. Good work. Did you ever hear from the girl or her family again?

Thanks Bill. You answered all my questions and I’ll bet most of yours!!!

It may not be a “Zephyr-type” story, but I’m glad you published it Jim. A worthy read.

Thank you for writing this story; I enjoyed it very much and am forwarding to a friend. I certainly found material to think about and I believe he will as well. I’ve changed my two wheel experience to bicycles; largely through fear of an experience like yours. I don’t like my actions to be bounded by fear; but there you go. I’ll see if I can help walk some people home tomorrow.

PS, sending in a long-overdue donation to Stiles.

Boy that was Long! Great human spirit! Ultimately you have to live within yourself, I’m constantly encouraged when that prevails… good luck.

A very good read. At 68 I recently broke my hip in a fall. After 6 months I have healed well but I believe after a certain age “walking bones” only heal so much. I identified with the grief/mourning pain as I lost my wife when she was only 46. I learned that when you are walking through hell, keep walking. There are many mysteries in life but the big one remains what comes next. We can’t know until we get there. It sounds to me as though you have found much peace. I hope you keep it. Thanks for sharing your story.

Thank you Bill, and Jim, for this story. I get the reticence to publish. I did have to take a cringe break in the hospital part. Much of it hit home for me. I had a life altering bicycle accident in Needles CANY in ’81, Moab ER sent me to G.J. It was a magical experience, but for me, despite the cringe-worthy damage, the only pain I felt was during treatment. It is amazing the impact a 2 second event can have on the rest of your life. Your Big Picture resonates with me. Mahalo

Wow!!! What an account! I worked in the medical records at the I. W. Allen Memorial Hospital in Moab, Utah one summer. It was an apprentice-type program. I learned a lot, though I decided not to go into the medical field. One thing I did note is that during that summer, broken bones were the most common condition treated in the ER at the hospital. One little boy broke an arm (I can’t remember how he broke it), and an elderly lady broke her hip in a fall. All the other incidents involved motorcycles. Before I married my husband several years later, I announced to him that he would not be riding motorcycles. So far he has complied!

Great read. It wasn’t really too long as time stood still while I read it because it was so damn compelling. I have strange parallel experiences…I too rode a large 2 stroke Suzuki in 1973 (T500), my then GF drove a Pinto, I’ve been on the pain scale many times and while I have not gotten to the 10 level, medical professional have told me I rate my pain too low. I especially appreciate the adice at the end.

Incredible real life story! thanks for sharing. I’ve always had a 400cc bike for my short commutes and errands around town. Even an older KZ400. Had a couple of “mishaps” but nothing major, very fortunate. Girlfriend, now wife, bought a brand new 1980 Pinto that we drove all over the place and road trips.

Thanks Bill, I feel blessed to have survived my motorcycle days. I volunteered for ambulance service here in Vernal, Utah, and even took a ride in the back once having broke my ankle in a MC accident. My boys saved me much worry by not getting the motorcycle fever in their teens and twenties.

I’m glad you wrote it and glad I got to read it.

Bill. I sincerely admire your ability to endure this horrible trauma. Your courage is remarkable. So happy you survived and lived a long productive life. You are really a miracle. And, I am so sorry you had to endure a life of pain caused by a negligent, irresponsible, immature driver, but you never gave up. You are an inspiration.