I’ve never written anything like this before — not in the 33 plus years I’ve been publishing The Zephyr. Not ever. It’s personal and it’s painful; it’s about mistakes I have made, and regrets I will carry to my grave. It’s about loss and unexpected events in our lives, and how we deal with them. We all seek our own paths — some find comfort with family and friends. Others turn to their church. Some try to ride it out on their own….still others seek “professional help.”

In the context of this story, it’s also a cautionary tale –– a warning to you about the mental health system in this country and how badly it can be abused, intentionally or unintentionally, by the people who oversee and manage that system. I believe that mental health services, when professionally administered by people with true consciences and a genuine concern for their patients, can be of great comfort to those dealing with grief and despair–the pain that can create serious emotional problems. But it can also be abused. It can cause even more damage to the very individuals the mental health “professionals” claim they are trying to help.

Everything you are about to read is true. I base much of it on the pages and pages of hand-written notes I made during my nightmarish experience. As you’ll learn, it’s a miracle I was even allowed to do that. This story is mostly about 72 hours of my life.

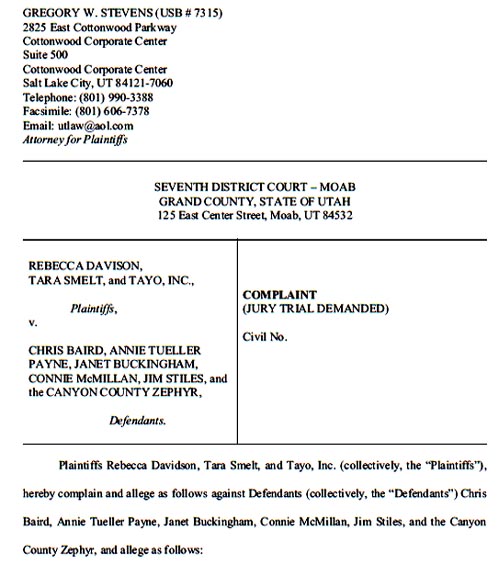

Finally, I don’t intend to to mention the real names of individual doctors, administrators, nurses, or even the hospital where all this played out. I have learned from personal experience that telling the truth and providing the unvarnished facts mean absolutely nothing in the realm of civil law. I don’t need to remind anyone that I (and others) endured almost three years of harassment, mental anguish, disillusionment, and financial loss, dealing with the defamation lawsuit that we faced several years ago. We won at every level of the justice system—all the way to the Utah Supreme Court. But in civil court, all one needs is the will and the financial resources to accuse anyone of anything. I’m not going to live through another nightmare like that. Not in this lifetime. But take this information seriously. This is what happened…JS

PROLOGUE: THE TERRIBLE YEAR(S)

It’s not my desire or inclination to dwell too specifically on personal events of the last few years, and many of you who follow The Zephyr already know some of the details. It probably helps to explain in general that I grew up in a very angry, unhappy family, with a mother who suffered from, but was never treated for, a lifelong mental illness. In fact, mental illness, alcoholism, and suicide, or the threat of it, has historically existed on both sides of my family. To quote Hank Williams, Jr,:

“Son, how did you get in this condition?”

“I’m just carrying on an ole family tradition”

Within my immediate family, an “unusual” childhood, to speak euphemistically, is one reason why I fled Kentucky for Utah so many decades ago. But in addition to my long ago personal history, this narrative requires at least a brief review of recent events in my life and how it led me to what happened next…

In 2016, as I mentioned, and most of you know, our lives were rocked by a $5 million defamation lawsuit that was filed by the former Moab City Manager; It was in response to a long investigative story I wrote earlier that year. The suit dragged on for almost three years. Though we won at every level, the experience took its toll on me and on my wife. It was like living constantly on the razor’s edge and I think it changed me, and made me edgier. Less patient. More critical. I was not a joy to live with, especially for those closest to me.

But beginning in 2020, the world fell in on us. In April, Tonya had a cancer scare and she endured surgery, just as the Covid-19 pandemic began; for eight months, we waited to see if she’d be okay. On December 2, 2020, after more tests, Tonya received news that there had been no reoccurrence.

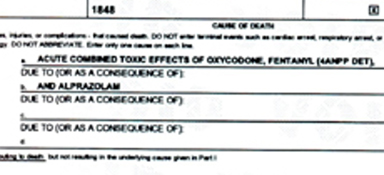

On December 3, the very next day, my younger brother was found dead in his home. The cause of death was kept quiet by his immediate family, who subsequently refused to allow us to attend his funeral. On my own, I filed for a copy of the death certificate. Weeks later, I learned that the “acute, combined toxic effects of oxycodone, fentanyl and Xanax” had killed him “within seconds” of ingesting those meds.

My 93 year old mother was in a nursing home in Lexington, Kentucky at the time, and the responsibility for her care fell to us. My brother had unilaterally managed her finances for years. Once I was assigned power of attorney, I was shocked to discover that he had misappropriated hundreds of thousands dollars of her retirement funds. Then my mother’s bank contacted me — two checks had been written on the joint account she shared with my brother. Combined they were for several thousand dollars. His signature had been forged and pre-dated to the day before his death. Someone in the Stiles family had found the checkbook after my brother died. The bank stopped payment and urged me to contact the county attorney, but no action was ever taken.

My wife did an astonishing amount of work, dealing with my mother’s remaining finances, taxes, medical payments, insurance issues, credit card bills, and trying to determine where all these previous credit charges and other extraneous expenses had come from. It was exhausting and spirit-crushing for her. Month after month, she dealt with the business end of this nightmare while I tried to deal directly and daily with my unstable and unpredictable mother. She sometimes called me as many as 40 times a day. At one point that spring, my mother was sent to the state mental hospital when she kept threatening suicide –– something she had done repeatedly since I was seven years old. The psychiatrist urged me to have her admitted for 60 days. My mother pleaded with me to let her return to her assisted care facility. I finally relented and she went back to Lexington.

In July, Tonya had yet another health scare, for another type of cancer. We waited two weeks for a diagnosis. Thankfully it was benign and surgery was not required. We both breathed yet another sigh of relief.

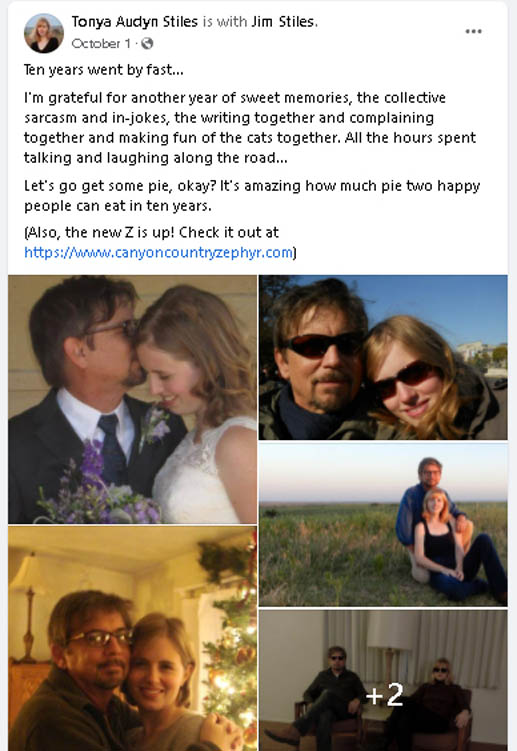

In late September, we learned that my mother’s physical and mental health had declined to the point where she could no longer remain at the facility in Kentucky. She was moved to a nearby hospital. Our tenth wedding anniversary was October 1 and we had planned another big road trip to the West Coast—to Oregon and Northern California, and then some time wandering the Great Basin of Nevada. Instead we spent the entire month arranging to move my mother to Kansas. We made a fast 2000 mile round trip to Kentucky to move her furniture and all her personal possessions from her assisted living facility. Tonya made virtually all of the hospital and insurance company calls, while I worked on the ambulance transportation.

But in the weeks before November 1, and my mother’s eventual move to a full service nursing home in Kansas by medical transport, I started showing worrisome signs of colon cancer. I had not been to a doctor in 20 years and had never submitted to a colonoscopy. I was really scared; it took weeks for me to share my condition with anyone. Finally I told Tonya and she urged me to see a doctor. We scheduled the test, and in mid-November, I endured the scope. To our surprise, it was not cancer. But I had a serious case of colitis, most likely related to stress. The treatment was miserable and only ended in early December.

Less than two weeks later, came the sudden breakup of my marriage. I did not see it coming at all. We had never discussed divorce, or separation, or even that our marriage was at risk. But I completely fell apart, turned to alcohol and Xanax and was either asleep or numb for almost a week. I had not put up a Christmas tree since I was a boy, but for the last twelve years, it had become a new and happy tradition for us. Suddenly knowing I would be alone for Christmas, after such an amazing, happy decade (for me at least), I even dragged our Christmas tree outside and left it on the porch. It was all despicable behavior on my part. Over the next few days, in a deep dark hole, I even contemplated, though never acted on, thoughts of calling it quits. I had the means to do it, but ultimately not the will. My wife flew to California to live with her mother; I never heard her voice again.

By Christmas, I had forced myself to stop self-medicating and though I felt terrible, my mind started to clear. But by then, my wife was fully and intractably committed to divorce, and nothing I could do or say now could alter her course of action. She wanted to move on and start a new life. I made a settlement offer which she accepted, and that was that (It took another four months to be finalized). But I was still in a very bad, very dark place mentally, and in terrible need of just talking to someone.

To make matters worse, it felt like The Zephyr was as dead as my marriage. I had no idea how to perform all the technical aspects of the online Z.; Tonya was brilliant at it and now, I didn’t know what to do. A day after Christmas, I posted its obituary online. I felt isolated like never before in my life.

JANUARY 3, 2022

Though I love the Great Plains and its people, most of them are, by nature, hesitant to intrude in the private lives of others. One almost has to be family or a lifelong friend to find that kind of intimacy. I get that and I respect their instincts to respect the privacy of others. And for me, it was hard, if not impossible, to ask for help. I guess it’s why, for the most part, I have fit in here. But I needed help from someone. I decided to make an appointment with a physician’s assistant (PA) I had met in a nearby town, when I was tested for cancer in November. I thought maybe she could recommend a therapist, or even prescribe an antidepressant.

On January 3, I drove alone to that small community for the appointment. But when the physical began, I experienced some kind of a breakdown, as I described the circumstances of my divorce and the events of the past year. It’s embarrassing to tell this story, but I began crying, and I could not stop. I told the nurse and the PA about the drugs and booze and dark thoughts that had affected me so profoundly a few weeks earlier. I had rarely used Xanax in the last ten years, and they always just put me to sleep. But this time, my reaction to the medication had affected me severely and in unexpected ways. Also, I rarely drank alcohol at all. I cannot stand the taste of the stuff. But in this situation I had resorted to many shots of whiskey.

But I could not stop crying. The PA and a nurse ran blood work on me (another lifetime first) and the results indicated that now, I did not have a trace of Xanax in my system. Nor any alcohol. In fact, as awful as I felt, the blood screen, according to the nurse, had been excellent, and did not suggest any chronic life-long addictions. But I continued to blubber like a baby and the nurse and PA were simply at a loss what to do. The Great Plains might be the last place in America, for better or worse, where being brave and stoic is the way most men try to deal with these kinds of crises. The medical staff simply didn’t know how to deal with me. Their awkward discomfort was as obvious as my lack of emotional control.

Finally, in desperation, the PA asked if I would speak with a counselor via Zoom about my emotional state. There are very few mental health options in this part of the country and she turned to the only facility she could think of. I finally agreed and spoke to a man I’ll call Casey, who was a screener for a medical center in a much larger community, about 75 miles away. I spent almost an hour talking about my recent difficulties in the wake of the pending divorce. I repeatedly blamed myself for the break-up, and we also talked about issues going back to my childhood. I was grateful to the therapist and found myself trusting him. He asked me if I might be willing to become an in-patient at a behavioral health unit at that larger hospital. He insisted that it would provide an opportunity for much more therapy and time away from my home. I had so many wonderful memories of the last decade and now it had ended so suddenly.

Being able to talk with a therapist at length appealed to me and I was under the impression, in fact, that Casey might be one of the people I would speak with. He acknowledged the fact that what I needed most was to talk to people who would listen.

He had also asked me if I was suicidal. Though I had described to him my terrible time weeks earlier, and my family’s history in that regard, I told him that I did not want to deliberately end my life. I admitted that “if I died tomorrow, I really wouldn’t care,” but that I didn’t want to take the path of suicide because, for one thing, I needed to outlive my mother. Second, I didn’t want that to be my legacy, though I have had other dark times over the last three decades. He said he believed me. I later learned he even included my comments in his report.

As I pondered a decision, both the PA and the nurse nodded enthusiastically —-they both felt that this was just what I needed right now. Up to that moment, I could have gone home, of my own free will. But l also recalled that for years, Tonya had wanted me to seek counseling to deal with my dysfunctional family issues. Until now I had steadfastly refused. But it occurred to me that perhaps, if I agreed to this, and showed I was willing to seek help, that she might reconsider the divorce. Finally I agreed. The staff thrust a stack of documents in front of me and I initialed and signed all of them. I didn’t know what I was signing, nor was I really capable of making a clear-headed decision. And I was by myself, with no advocate or friend to offer a more measured opinion. No one, including the screener, provided me with any specifics regarding the program I had just agreed to. I assumed, as he said, that it would be a quiet place, a sanctuary for me to relax and especially to talk. I had spent weeks totally alone, with rarely any contact with anyone.

No one mentioned any restrictions or elimination of my freedoms. But I didn’t ask; I assumed that everyone was acting in my best interests. I could have walked out the door, but I agreed to give therapy a try. Whether the PA was uninformed about the conditions at my next destination, or she withheld the information, thinking it was “for my own good,” I’ll never know. The PA wished me well and left the clinic. I never saw or heard from her again.

The behavioral unit in the distant hospital was unable to find a room for me on Tuesday so I was admitted for one night at the local hospital. The plan was to transport me the next day. I assumed that conditions at the behavioral unit would be similar to a hospital room, and again, with many sessions in therapy.

I inquired with the nurses about transportation and no one was sure. I told them I could just drive myself. One nurse thought that while it might be an ambulance, I’d probably just sit in a jump seat, since I wasn’t really ill or injured. I had a small pack in my car that contained toiletry essentials and no one thought it would be an issue. In fact, the nurse jokingly commended me for being so well-prepared. That evening, as the nurse in charge, I’ll call her Janie, made numerous calls to the Unit, I was sitting next to her. On several occasions, I noticed a puzzled look on her face as she tried to answer questions being asked of her about me. Finally she turned to me and said, “I don’t think these people really get who you are or what your problem is.”

I asked her what she meant. The nurse replied, “Well, like just now, they asked me if I thought you would try to sneak drugs into the hospital by hiding them on your body somehow.” It troubled both of us, but we concluded that perhaps they were simply standard questions that were being read from a form.

I sat with Janie and another nurse for almost two hours. They heated up a microwave dinner for me and we talked about our lives—theirs as well as mine. Janie was married to a farmer and it had been a rough year. Finally I was moved to a room. A couple more nurses made me comfortable and could not have been kinder. And no one treated me like I was a man with a serious substance abuse problem. I told them, in fact, that our conversations had been the best therapy I’d received since my life started falling apart, almost three weeks earlier.

JANUARY 4-6, 2022

The next afternoon, a man appeared at my door. He looked nervous. I was stunned to see that I was about to be placed in a heavy steel gurney with many nylon physical restraint straps. I hesitated and he looked like someone prepared for a fight. But he quickly realized I wasn’t a menace to him. He was the ambulance driver and he explained that it was their standard procedure. He promised not to make the straps too tight. I was shocked but allowed him to proceed. Then he saw my pack of toiletries and told me I couldn’t bring it along, which also surprised me. Why would this be a problem?

He put me in an ambulance where I met the nurse who accompanied me. She sat right beside me and hooked me up to a monitor; she explained to me that it was also required. I was still oblivious to what was coming and so the nurse and I chatted amiably for most of the trip. Finally she said, “I’ve never had a patient like you.” I wondered what she meant. She said, “Either they’re almost comatose from drugs or they’re sort of hyper. You seem real calm.” Again, I was just grateful to talk to someone. She started telling me about her own life. She had cared for an old man for years and after he died, she was shocked to learn that he had willed his home to her. It was a stunning surprise, but it gave her a warm feeling. I could understand why.

As we kept driving north, I noticed the beautiful sunset out the ambulance’s rear window. She let me pull out my phone and take a few pictures. She even allowed me to take a photo of her; she said, “I think you’ll get out real fast. You seem like a nice guy.” I thanked her, but still, even now, didn’t grasp what I was heading into.

An hour later we arrived at the hospital. I was removed from the gurney and placed in a wheelchair. Two uniformed, armed security guards accompanied us. I was taken to the 3rd floor, through two automatic heavy steel security doors, and into a large open room, with smaller private rooms along the perimeter. At Room 315 they stopped.

I was met by three female nurse/administrators who told me to go into the room, and remove all my clothes except my shorts. They handed me a gown. I said, “You must be kidding me.” None of them smiled. Then I had to surrender all my personal possessions to them. I was incredulous. They took my wallet, my phone and charger, my glasses, my wedding ring, my belt, my jeans, my watch, my shirt, and even my socks. I was allowed to keep my reading glasses. But they would not allow me to keep my regular glasses. “Only one pair per patient,” they said.

No one had told me that these were the conditions I could expect when I arrived. Had I known, I would NEVER have agreed to it. I tried to argue that this was not what the Zoom therapist had described, and I insisted that I be allowed to go home. I had not even locked my door that morning at the house and now the nurses would not allow me to make one phone call to a friend at home, to lock the door and deal with my cats.

I was particularly upset about my phone. On Tuesday afternoon, the official divorce settlement arrived as an attachment in an email. But the PA at the small clinic knew it was going to add even more grief to a really hard day. She suggested I wait until I reached the Unit and look at it with a therapist. I told them I needed my phone. But the staff was implacable.

After I put on the gown, the three staffers interviewed me with a series of questions that I would grow accustomed to (and weary of) over the next 48 hours. It was in the form of a standardized questionnaire and they were always the same. The answers were supposed to provide the “baseline data” for my emotional improvement or decline.

And so again and again, I responded to the questions—On a scale of 1 to 10 how depressed are you? How depressed had I been over the last 30 days? How sad was I? They asked me if I was suicidal over the last 30 days. They asked if I had had any homicidal thoughts. “one to ten.”

Then they asked me if I had contemplated or attempted suicide today. I told them “no,” and one of the nurses said, “Wait a minute…we heard that you tried to kill yourself today.”

I was dumbfounded. I explained that I had spoken with a counselor about the hard times before Christmas and how during that week, I had said crazy things that I regretted, but that I had not attempted suicide then or today, and referred her to my Zoom chat with Casey. It was clear that they didn’t believe me and the questions felt more like an interrogation than an effort to help me. They made me walk down the hall to a scale and weighed me, led me back to Room 315, and started to leave. I asked them about therapy sessions—when would they start? How many hours a day would I be able to speak with someone? They were vague, even evasive.

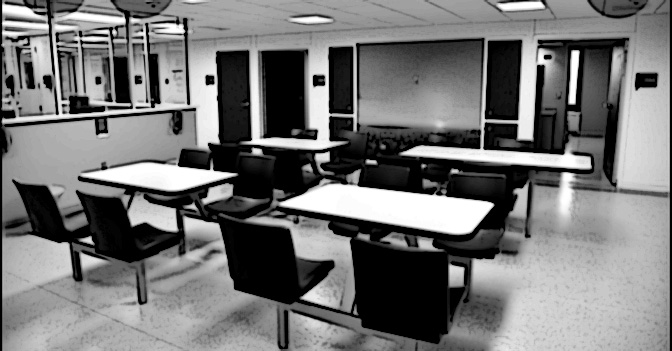

My room was barren. There was no television or a lamp, or even a clock. No pictures on the wall. The bed was very narrow and did not have sheets. Instead a nurse later explained that they used “safety sheets,” a quilt-like non-tearable material. It was non-tearable so that it couldn’t be torn into strips to presumably hang oneself. The pillow was tiny, about the size of a box of crackers, and of the same material. The room, in fact, was for violently homicidal or suicidal patients with chronic hard drug or alcohol issues. It was more intense than a prison cell. The blinds on the window were pulled tight, sealed within the glass and the lever to open them had been removed. The only light came from one severe fluorescent ceiling light. All the bath fixtures were covered up by steel plates and even the shower faucet handles were recessed into the wall. There were no sharp edges.

Sally, the night nurse came and gave me an old sweatshirt and a pair of sweatpants to wear. At 9 PM I was told it was “snack time.” She said it would be my last chance to eat until tomorrow. I ate half a sandwich and returned to my room. Nurse Sally advised me that they would be checking my vitals at 10 PM, 2 AM and 6 AM. I could not believe what was happening. In addition to the vitals checks, Sally returned every 20 minutes throughout the night to see if I had harmed myself. She wore rubber soled shoes that made a squishy, squeaky sound as she walked. I could always hear her coming, a hundred feet away— I could not sleep at all.

At the 2AM vitals check, she took my blood pressure and I could see the screen–it said 220/110 and I knew that was a dangerous level. I pointed it out to her, but she said nothing. The nurse left the room but came back a few minutes later and said that the BP I had seen was “someone else’s” and that MY BP after a second check, was now much lower. At 7AM, Sally returned with yet another person who had come to draw blood. I resisted at first but finally allowed it.

Again, I told the nurse that I had never been told I was coming to a place like this. When I asked her about therapy, she looked at me like I was crazy. She replied, “You won’t get much therapy here, maybe 40 minutes a day— THIS is a detox unit.” It was at this moment when I KNEW I must be in the wrong place. I said I was here for therapy, not this. I had come here to get better, not worse. She ignored me and left.

At 7:30 AM, I was given another “assessment” — the same questions about my attitude toward death, toward depression, suicide. I offered my honest opinions.

‘YES, I am depressed,” I said. “My wife suddenly left me after 12 years. I’m taking it badly. In the days after she left, I fell apart and abused alcohol and Xanax. It’s been a struggle. Would I like to be dead? Probably. Do I want to kill myself? No.”

The nurse was unmoved. All that mattered was that I answered her questions about my mood. On this “one to ten” scale. It was utterly absurd, but I couldn’t find the humor in any of it.

At 8 AM, yet another nurse advised me that breakfast was ready. All the patient breakfasts were “cooked” in a large stainless steel oven, and in it were trays assigned to each of the patients. To receive a meal, the nurse asked for your date of birth. I was told I had to eat at the tables in the center area, and could not take food back to my room. When I was done, I was instructed to return my tray to another multi-tray holder. Each tray was marked by name and then inspected to see how much I had eaten ( I know this because a staffer told me later they were concerned about my poor appetite; I lost almost 5 pounds in two days.)

The nurse handed me a menu and asked me to designate what I wanted for the next three days. I said, “No…I don’t plan to be here that long,” and handed it back to her. She looked at me scornfully, shook her head and said, “Listen to me…Play the game and things will go easier for you…Keep acting like this and who knows how long you’ll be here. It’s better to cooperate.”

I asked if she was threatening me. She said she was not trying to be threatening at all, but she warned me, there were rules on this floor that had to be abided by, and that my resistance would only make things worse. “If you want to get out of here, you’d better listen to me. Or there could be much more trouble for you.”

After breakfast and for the rest of the morning, I rarely saw anyone. The floor looked almost abandoned. I was told that the staff was in conference and that they would come talk to me later. There was no sign of a therapist giving assistance to anyone. I wanted to write down everything that was happening to me, so I asked the one nurse on duty, who occupied a highly protected glass enclosed nurses station in the middle of the room, for a pencil and some paper. I started to return to my room, but the nurse stopped me and said I could only use the pencil in the center room where the tables were. She warned that I also needed to return the pencil when I was done or it would “mess up our pencil count.” They counted these stubby little two-inch pencils.

I also asked the nurse if I could make a phone call. This was the process— there was a wall phone mounted just below the glass enclosure of the nurses station. (You can see it in the image above) The nurse sat a foot away, on the other side of the glass. If I wanted to make a call, I wrote the number on a piece of paper and held it against the glass. The nurse would dial the number, make the connection and advise the recipient that “Jim Stiles is trying to call you.. will you accept the call?” Once it was approved, the wall phone rang and I could talk. My first call was to the clinic I had first visited. By coincidence, it was Nurse Janie who answered. I had no privacy, and in almost a whisper, I explained to her what had happened and what the conditions were. Janie was shocked. “That can’t be!” she said. “You were supposed to just get therapy…they took away your clothes and your phone?” She promised to immediately contact the PA and she apologized. But I never heard from the PA at all. Whether she made a call on my behalf, I will never know.

Then I called my friend Dave Gerstner, who lives in my hometown. He was shocked and furious and told me he’d call an attorney. Five minutes later, the lawyer called the Unit and the nurse connected me. He was as shocked as Dave, but it was already Thursday and past noon. If he tried to get a court order to have me released, it would never happen before the following Monday. In the short term, it was an impossible situation. He told me to just ‘hang in there.’ I went back to the tables and kept scribbling notes.

Finally, the same nurse who had served breakfast, entered the big room and saw me at the table writing. She walked the length of the Unit and stopped. I’ll call her Angela.

“What are you writing?” she asked me.

“I’m documenting every detail of this wretched, miserable place,” I told her. I was desperate enough that I decided to play my “I’m a journalist” card. I wrote the Zephyr website on a piece of paper and asked her to give it to whoever was in charge. She asked if she could sit down and talk to me. Of course, I replied.

Angela glanced over her shoulder to be sure no one else could hear her. “Look,” she said, “I know you think I was threatening you a while ago, and it did sound like that, but I’m trying to help you right now, not hurt you…you don’t understand how this place works. The head psychiatrist wields all the power here. If she says you’re not ready to go, you won’t go anywhere. Your best chance of getting out of here the fastest is to just keep quiet and be cooperative.”

I looked at her differently now. I believed her; she was trying to help. But it still made no sense. I told her that I had never experienced anything like this, and it was coming in the aftermath of the worst month of my life. I said, “This place isn’t offering any help at all…it’s making everything even worse than when I arrived. This drives people to insanity, not away from it.”

The nurse smiled bleakly. “I don’t know what else to tell you except that what I just said is your only chance to get out of here soon.” While she was there, I had another question. The entire floor was cold…maybe 60 degrees. I asked if there was a problem with their heating system. She shifted awkwardly and said, “No…actually by keeping it cold in here, it reduces the chance of violent behavior by our patients. We don’t want any riots.”

There were only six or seven other “patients” residing on this floor, but I rarely saw any of them. Almost everyone stayed in their rooms. All of them looked utterly drugged out. Like zombies. Not once did any of them ever speak, or even look at me. I felt like I was in a scene from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” One man walked to the nurse’s station and asked if there were any books to read. She shook her head and said, “Just what’s on that shelf.” He walked over to the bookcase—it was empty.

Finally, in the early afternoon, two staff members came to visit me. I believe they might have been administrators there. They said that another person, the chief psychiatrist, would be visiting with me soon. As Angela warned, she was THE person in charge. But we waited and waited, and she didn’t show, so the two women proceeded without her. The administrators asked me to tell my story, my family history, and the incidents at Christmas with my wife. Then came more survey-like inquiries about my current state of mind, and as always, “on a scale of one to ten.” Finally, as I was about two-thirds of the way through my long narrative, the head shrink — I would learn later that she is always referred to by staff as “The Doctor” — came into the room and tried to get caught up on what we’d already discussed. It was difficult to regurgitate several decades of family history, but she insisted, and I did my best.

More than anything else, I tried to explain to them that I was never told these were the conditions I could expect and especially the fact that I had somehow, unknowingly surrendered all my personal freedoms. In my entire life, I had never found myself enduring these kinds of restrictions. I was really hoping that they might relent and release me and I thought that two of them were sympathetic to the idea. But the psychiatrist was unmoved. She told me that I would stay at least another night, and they would “reassess” my condition” tomorrow morning. She also told me that before I left, I must establish a “safety plan.” They wanted someone in my home town to go to my house, and remove all medications and all firearms from the premises.

She demanded that I agree to out-patient counseling and that I start taking an antidepressant. I was beginning to understand more fully what Angela warned me about— If I wasn’t cooperative, I wasn’t going anywhere. The psychiatrist controlled my future. I agreed to the plan and suggested they contact Dave Gerstner, who I had called earlier, and knew what was happening..

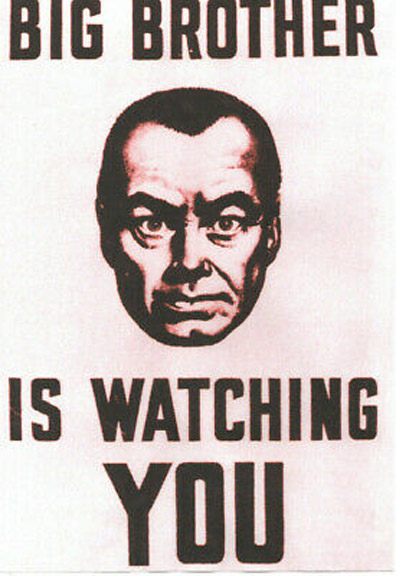

Throughout the remainder of the day, I was visited again and again by staff, but never for therapy. Basically my therapy ended with the Zoom call on Tuesday. Instead they seemed to be assessing and reassessing and re-reassessing me, and trying to decide whether it was wise to restore my freedom. And like the nurse, they both warned me that while they could make recommendations, it was “The Doctor,” as they called her, who had the final say. In fact, I began to get the same vibe from them that I received from Angela. All decisions channeled through The Doctor. To each of them, I would tell the same story—that I had come here for therapy because I needed people to talk to. I reminded them of my specific views on suicide to the Zoom screener. They also seemed sympathetic, but again—it’s up to The Doctor. They even used the term with a hint of sarcasm. And perhaps with a touch of fear for themselves. It all felt Orwellian to me —as if The Doctor was straight out of the dystopian future of George Orwell’s “1984.” Big Brother was now Big Sister. And The Doctor’s associates seemed almost as fearful of her as the patients.

The Doctor held the power; yet, she only spent about 20 minutes of the conversation in the room with me and the administrators— I never had any one-on-one chats with her at all. I thought later, maybe I should consider that a rare blessing.

By 5 PM, I was falling apart with fear. I had never been scared like this in my life. It was an entirely different kind of Fear. I had finally convinced Angela to retrieve the window blind lever and raise them so I could see the sunlight. I was surprised to discover that since I arrived, the weather had turned bitter cold and had dumped almost a foot of snow. Just beyond the glass I could see the real world and free people, just a hundred yards away, driving their cars, walking the sidewalks. I’d never been so envious of such simple movements that we all take for granted. All I wanted was my freedom.

It was becoming clear to me that my early release depended, in fact, on how well I could lie. Instead of being honest, my goal now was to please The Doctor. I was fearful of doing anything that might displease her or anyone on the staff. At one point that afternoon, I had started to put a pencil in my pocket as a souvenir of this nightmare, but then thought better of it. I was actually scared that if they found the pencil, I would somehow be punished.

It was straight out of 1984—“What number do you see?”

I had never found myself in a position where I could not walk out a door and leave, regardless of the consequences. Earlier I had told The Doctor that it should be my choice, not theirs, and I told them that I was even concerned about my physical health. My blood pressure had been swinging dramatically in the last few days and this was not helping. The Doctor said sternly, “We have meds we’ll give you for that.”

I said, somewhat defiantly, “What if I don’t want the cardiac meds? It’s MY choice.” She glared at me and soon left the room. Now I worried that my earlier candor would cost me dearly.

As I fretted over my “performance,” I started to feel dizzy. My head was spinning, and I kept losing my balance. I went to the nurses station and asked Angela if she could check my blood pressure. Later she told me that just looking at my pale clammy face worried her. She thought I was about to pass out. Now my BP was rapidly falling and she called it “worrisome tachycardia.” My pulse was 140 beats a minute. She said, “you’re getting into stroke territory.”

Up until now, I had refused any form of medication. Since they claimed I had an addiction problem, it seemed like a good idea to avoid asking for meds. But now I could barely stand and I was shaking like a leaf. I asked Angela if it would work against me to take something for anxiety. (Earlier, I had noticed that almost every patient in the Unit approached the nurses regularly with the same request). She immediately said, “No… it will not work against you…It will be to your favor if we give you something.”

That surprised me. Just like the other staff members, Angela advised, “It is very important for you to be calm and in good spirits when you are given your next assessments. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you?” I finally grasped the meaning. I needed to be much better for my next survey.

She gave me an “anxiety” pill and it helped. At 8 PM, the night nurse came by to assess my mood again. I said I was feeling better. I gave myself higher numbers for all questions. At 9 PM, the nurse came again to give me a sleeping pill. This medication, she said, was called Seroquel. It was prescribed by The Doctor. I slept for almost 16 hours. But not peacefully. I was severely overmedicated. In the middle of the night, I half awakened to a loud screaming noise inside my head, and my brain was flashing bright images under my eyelids. I felt like my heart was about to explode. But I knew that soon, the 2 AM vitals check was coming, and if I complained or even mentioned these symptoms, it might jeopardize my departure from this hell hole even more. When the nurse came, it was Angela…I said nothing and neither did she. By the next morning, I was just like everyone else on that floor— a zombie

The previous evening, when the nurse gave me the Seroquel, another nurse handed me yet another tablet. It was a vitamin pill. I asked what this was for and she said, “Well…we were told that you are an alcoholic.” Because I had told someone else, on another day, that I had briefly resorted, weeks earlier, to alcohol while dealing with the divorce, it had gone on to my chart that I was someone with a chronic drinking issue.

WAITING TO ESCAPE

On Friday morning at 8 AM, the nurse woke me up— time for another assessment. This was the ‘big one.” I reminded myself how much better I was supposed to say I felt. She went through the checklist. I raised my numbers significantly. I even injected some cheerful optimism into my voice. The nurse actually smiled.

“So,” she said boastfully, “Maybe all this has been more effective than you were willing to admit.”

“Yes,” I lied. “I guess it has.”

At 10 AM, The Doctor and the two admins came to my room and told me that they had spoken with Gerstner. He had agreed to remove those items from my home, and that he would also come and pick me up later that day. But I had to agree to the “Safety Plan” which required that I take the antidepressant medication, Cymbalta; they also insisted it was mandatory that I visit their affiliated counseling organization on Monday, January 10. If I didn’t agree, they would not release me. A sarcastic reply appeared inside my head, floating over me like a comic strip bubble. But I knew I was dealing with people who had been denied a ‘sense of humor gene’ since birth; for once I kept my mouth shut. At that point, I would have agreed to anything.

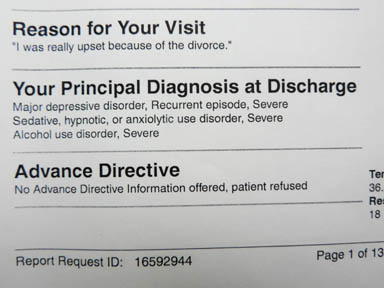

At about 3 PM, yet another administrator came to my room, and asked me to come out to the center area, to one of the tables. She had a thick stack of papers to review with me. Yet again, in order to be released, I had to promise to attend a counseling session the following Monday. According to the language in the document, it was compulsory. I had to agree to take an antidepressant and that I needed to fill that prescription before the day was out. I glanced at the pages as she flipped through them. I spotted a short “diagnosis” from the chief psychiatrist—The Doctor. She had written this:

“Major depressive disorder, Recurrent episode, Severe Sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use disorder, Severe Alcohol use disorder, Severe.”

Even though I had not spent ONE MINUTE alone with The Doctor, and even though my blood work had shown I was alcohol and drug-free, and even though I had told them I rarely if ever drank alcohol…despite all that… The Doctor had written into my hospital record that I was a severe drug addict and alcoholic. “Severe Alcohol use disorder. Severe.”

But what could I do? This most recent administrator was as brittle and cold as the chief shrink had been. I feared that to argue now with this insane diagnosis would have put me back in the tank. So I signed my discharge papers without comment.

The woman finally unlocked a cabinet and returned all my personal items to me– she had previously returned my clothes, except for my jacket. She said it had a drawstring on it and I might still try to hang myself. I looked at my wallet and immediately noticed that they had gone through it completely. Nothing was where I normally kept my various IDs and credit cards. Even a law enforcement officer needs permission to look inside a wallet. In the Unit no one even told me they intended to examine the contents. But again, I said nothing. I was too scared to complain. I just wanted out of there.

I went back to my room for a few minutes, and waited for word that Dave had arrived. Angela stopped to say goodbye. I thanked her for her honesty and advice. She nodded and told me she was relieved that I was able to decipher her subtle warning. And then she told me something chilling. She said, “Remember when, at first, you refused to fill out the three day menu?”

I nodded. Angela said, “If you had continued to disobey, The Doctor would most likely have sent you to Larned,” as an incorrigible. Larned is the state mental hospital for extreme mental patients. It has a notorious reputation. Almost in tears, I thanked her once more. She went off shift and I never saw her again.

Finally the administrator who had reviewed the documents with me, came to the room and told me that Gerstner was downstairs. She escorted me out of the Unit, through the double security doors, down the elevator, and to the main floor of the hospital. As we were entering the elevator, she asked me if I needed to retrieve my “notebook.” I had no idea what she was talking about, so I simply said ‘no.’ She looked at me disapprovingly and said, “So…it sounds like you haven’t been very cooperative during your stay. Did you refuse to attend the group sessions?”

I said, “Group sessions? There were no group sessions. There weren’t ANY sessions…in fact, there was no therapy at all during the entire 48 hours I’ve been here.” She looked puzzled but said nothing.

( It’s just an interesting side-note but during my stay at the Unit, I never saw one male employee–it was a 100% female staff, and most of them were six feet tall or more. So not only did their staunch defense of their actions make my state of mind even worse, I felt shorter than usual.)

Finally I could see daylight ahead. I was met at the main entrance by the most beautiful human being I have ever seen— Dave Gerstner. And by fresh air. It was the longest period of time in my life that I had been deprived of the outside, and of real God-made oxygen. It was a cold breeze but it felt wonderful. I gave Dave a hug and came damn close to crying again. But this time tears of gratitude.

Dave and I walked to his car and started for home. First we stopped at the pharmacy and picked up my prescription as ordered. Then we drove to the clinic where I had left my car on Tuesday. It was about 3 degrees out and Dave waited to be sure it started. My little car fired right up. He waved goodbye and I made the last 50 miles home in the twilight. It felt glorious to be free and alive in these wide open spaces; the afterglow of sunset lit up the western sky. It was the most beautiful sunset I had ever seen. All I wanted to do was to be home, to hug my cats, and sleep in my own bed. An hour later I was back. That part of my nightmare was over.

THE UNIT ‘FOLLOW UP’

I was supposed to see a counselor on the following Monday morning. In fact, as noted earlier, they had said it was required. But Dave and I talked about the situation, and in addition to returning all the items The Doctor had told him to confiscate, he agreed that this was pure intimidation. “What are they going to do if you fail to show? Will they have you arrested? The sheriff would be on your side in this mess,” he concluded. So on Sunday, I called the office and left a message. It was a 30 second version of what I’ve just written. The counseling office never called back..

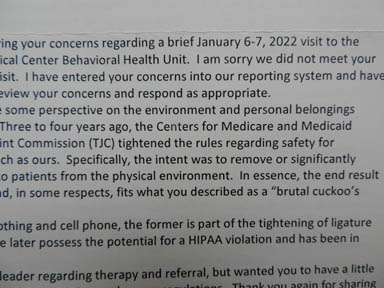

But I wasn’t done with the Unit or The Doctor. On Sunday evening, an email from the Unit appeared in my inbox. Incredibly it was an online survey from the Unit , asking me to rate my experience. Of course, I had grown accustomed to the “1 to 10” surveys I’d endured while I was incarcerated. Now they were sending them via the internet. But now I could also be honest. Referring to the experience and the therapy they were supposed to have provided, I gave them “ones” from the first to the last question, and in the limited space I was given for “additional comments,” I expressed them freely as well. Days later, I received a letter from their “risk director,” whose reply was as predictable as one could dread.

“Thank you for sharing your concerns…I am sorry we did not meet your expectations.” It was a boilerplate response, but he did want to reply specifically to my complaints about the physical restraints and the fact that they confiscated my personal belongings.”

He insisted that recent “tightening of rules” had made it necessary to “remove or significantly mitigate the ligature risk to patients.” Then he added, “In essence, the end result is a stripped-down unit and, in some respects, fits what you described as a ‘brutal cuckoo’s nest.’”

So the “risk director” even acknowledged the term himself— I had just been released from the “cuckoo’s nest.”

I replied by letter, and told him that for patients who NEEDED that kind of treatment and restraint, and stripping them entirely of their personal property was probably and regrettably required. But I wasn’t a chronic drug addict or an alcoholic. The blood work results proved it, and I had agreed to the visit in order to receive therapy; yet they had sent me to a “detox unit.”

A week later, I received another letter from the Unit—this time it was a six page typed letter from one of the staff. It was more of the same. The letter described in detail the protocol required for that unit and she insisted that they had followed all the rules. And then I started receiving the bills. Finally I copied the original letter I had typed when I got home, and mailed it to the CEO of the hospital corporation. He never replied personally, but a few weeks later, a letter came, advising me that while they felt they had done nothing wrong, the hospital administrator had decided to cancel the balance of my bill. To me it was a classic nolo contendere reply —they just wanted me to go away.

In a way, they still won. As I mentioned in the introduction, from The Zephyr’s previous legal nightmare, I know how civil law works. I know what kind of power the attorneys employed by a corporate hospital can wield against an individual. Facts don’t matter in the filing of a lawsuit. Ultimately they do, but getting there is the ordeal that I would never want to confront again. I’d love to expose “The Doctor,” who I believe had issues of her own, but it’s not worth it. For sure, all this has soured me on the viability, the effectiveness, and even the motives of the mental health industry — and maybe ‘industry’ is the word that tells it all.

EPILOGUE.

If there was one positive take away from my visit to the cuckoos nest, it was that the “experience” briefly took my mind off all the other difficulties in my life that had caused me to seek help in the first place. For three days, I had been consumed by the desire to simply survive and get out of there. Now, I was right back where I started, and with this nightmare added to the list.

I was never able to find a counseling service that I trusted and, to be honest, I didn’t try very hard. How could I possibly know, at first glance, that a change of therapists would be any better? Or worse? I wondered if The Doctor shared her “diagnoses” with other mental health services. Is there a database for people who have been diagnosed as “severe alcoholics?” Even if they can’t stand the taste of booze to begin with? Am I on some kind of a “watch list” now? Have I been “red flagged?” It reminded me of yet another Seinfeld episode, when Elaine seeks medical help for a rash, but her doctor takes issue with her ‘attitude.’ Her negative comments went on to her “chart,” and she was marked for life.

I have wondered since my escape if this was a rare exception to the kind of treatment these “behavioral health” agencies provide, or is this IT? Was this the way the industry operates now? One bewildering aspect of my experience still troubles me. As I mentioned earlier in this narrative, the therapist I spoke with via Zoom made some very intuitive observations, based on what I had shared with him about my life. His concerns about me seemed genuine; his suggestion that what I needed more than anything was the opportunity to talk to someone was correct. I repeated that need to him again and again.

So…even if the staff at the small clinic was unaware of the conditions at the Unit, surely this therapist was. Is it possible that even he didn’t know the hard facts about that prison? Or was he just lying to me, thinking he was going to lock me up and even take my socks away from me, because he was concerned for my safety and had concluded that it was “in my best interests?” Did he withhold information from me, for fear I’d then reject his suggestion?

Was his lack of transparency a corporate policy, based on economic concerns? The bill from the Unit was almost $10,000 for the 48 hours, and Medicare paid for most of it, so they probably still met their profit margin. Was his suggestion based on a genuine concern for my well-being or was it purely determined on a profit/loss basis? I don’t know the answer to that question and while I make no recommendations to others, it’s why I’m telling this story. I would never ever allow myself to submit to this kind of “therapy” again.

Instead, I came back to the life I had briefly left. Now I felt that it was up to me, and only me, to put my life back together. I could have used one, good solid lifelong friend. But in my life, most of those good friends died years ago—Bill Benge, Jim Conklin, Reuben Scolnik, Herb Ringer, Bill Koci, Gene Schafer…the pals I saw every day…all of them are gone.

I remember once, twenty years ago, I was caught in another sad hard time, and it had taken its toll on me physically and mentally. Gene Schafer heard I was in the dumps and rushed down to my place. He knocked on the door and at first I wouldn’t answer. He kept pounding and finally I relented and opened up. Gene stared at me a second, and then said, “Goddamn Stiles. You look like shit!….I’m gonna go get you some steaks.” He turned and went back up the street to his house. A minute later he was back at my door with a stack of butcher paper-wrapped meats from his well-stocked freezer. Gene died in 2011 …I will love and miss that man for the rest of my life.

Meanwhile many Zephyr readers contacted me, urging me to keep The Z alive. Readers continued to send Backbone contributions. I had many sustaining members and only two cancelled. I decided to give it a try. In early February, I drove out to Utah, where the Zephyr’s webmaster and one of my few dear remaining friends, Ricky Richardson, did his best to tutor me on the basics of WordPress and “SendinBlue,” the service we use to email Zephyr readers. He was as patient as he could be, and more than I deserved. I came back home, and tried to put his lessons to good use.

But at the same time, my mother’s health began to decline rapidly. She entered hospice via her nursing home in early February, just after I returned from Utah. She and I made a sort of uneasy peace between us, each of us forgiving the other for past transgressions, real or imagined. It seemed to help both of us. Or at least I thought so.

At 7 AM on February 16, the nurse called me and said my mother was “actively dying.” When I arrived she was still breathing, though semi-conscious and gasping for breath. I looked around the room and realized that since my last visit, she had ordered a nurse to remove every photograph of me and place them in a drawer. Only my brother’s photos remained. I met the hospice nurse soon after my arrival, and she administered more medications. The nurse was sure my mother would pass before noon, but she clung to life for another 10 hours. I was there the entire time, though I don’t think she knew it. Throughout her death struggle, she stared at the opposite wall, with an incomprehensible and bewildered look on her face. I held her hand and stroked her hair, and I’d try to talk to her, but she just kept staring at the wall.

Finally, at 6 PM, my mother died. She now lies in the earth, beside my father’s grave, at a lovely cemetery called Cave Hill, in Louisville, Kentucky.

While I dealt with matters related to my mother’s death—the Medicare and social security bureaucracy alone was bewildering — I continued to develop my skills using WordPress. Many calls with Ricky, the most patient man on the planet, followed. Finally, as all of you reading this know, on March 14, 2022, the anniversary of the very first Zephyr, and the day Ed Abbey died, I posted the first “Zephyr Blue Moon Extra.” I had a few missteps but overall I was satisfied and so grateful to Ricky, who I think was downright proud of me.

A month later, one of my beloved cats, Possum, who was born with bad kidneys, finally succumbed to his chronic illness and I lost him on April 25. I still have my other two “boys,” Rambo and Rascal, who give me comfort and a good laugh; they have both been a blessing to me. (In a future Zephyr Extra, I will explain why I believe one of them is an extraterrestrial from a distant star system). I think they may have provided the best therapy I’ve received so far, though losing Possum was one more blow.

There was still more to come, that caught me completely by surprise. In early May, a friend in Moab emailed me to ask if I knew that my ex-wife had started her own “social media platform,” and that three longtime Zephyr writers had jumped ship to join her. I had no idea. Tonya was under no obligation to contact me—she had already cut the ties. But the three writers had been friends of mine for as long as 30 years—the father of one of them had married Tonya and me a decade ago. I had known Pastor Don Falke’s son Damon since he was a boy.

Then I was made aware of a new book by former Zephyr contributor Paul Vlachos. Paul had been a Zephyr fan and supporter for 25 years. When I discovered his talents as a photographer, I invited him to be a regular contributor. Ultimately, after a decade, he turned his Zephyr contributions into books and we were delighted. I wrote the foreword for the first book, released a couple years ago. The second installment was published in March. This introduction was penned by Tonya. It was impossible to avoid mentioning The Zephyr at all, so she wrote this:

“For a while I was publisher of a bi-monthly online periodical—The Canyon Country Zephyr…Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately…a cosmic joke of timing occurred, and things went sideways for The Canyon Country Zephyr. As I’m writing this, the fate of that periodical is unclear. It may be dead. It may be on extended life support. All I can say with certainty is that the Z will not be what it used to be….And that’s ok. The website was always just a playground for Paul…I knew from the outset that his work was bigger than the address at which it happened to appear.”

*****

It’s been eight months since December 17— it feels like forever ago, and just yesterday—all at once. I still run my left thumb over my bare ring finger, where that special gold band resided for over a decade. Now I live my life day to day, and probably spend more time remembering the past, for better or worse, than looking forward. I no longer have a “best friend,” someone like Bill Benge, that I saw every day and who was like a brother to me for 30 years, But I am still lucky to have good friends like Dave, here in town, who had to leave his own business in the middle of a Friday afternoon and drive a hundred miles to rescue me from the Cuckoo’s Nest. And his wonderful wife Monica. I still see them often. And so many good people here, who care about my well-being, but are just lost for words.

Or far away friends, some back in Utah who still check in with me regularly, like Jami Bayles, Marjorie Haun, or Kay Shumway in Blanding, Brandon Hill and Ali Sabbah up in Salt Lake City. or Stacy Young in St. George. And Bill Seabold and Glenn Tindall in Kentucky. My friends, the Boothroyd sisters, Linda and Carolyn in Vermont. Cathy Berrier in France. Donna Andress in Nevada…And more. All of them have been very kind and caring — I don’t mean to diminish their importance to me. I value their support and goodwill. They’re just so far away.

But more than all the ‘stuff’ that came later, I still dwell on those awful weeks in December and January, more frequently than I should. And the year that preceded it. I’ve wondered if there was anything I could have done differently. Of course there was. Knowing it’s too late to change anything, it’s still difficult to avoid agonizing over the ‘what ifs.’ I also know that because of all these events, I barely resemble the man I was eight months ago, or a year ago, or five years ago. I think (I hope) that I have emerged from the other side of the Black Hole I’d been trapped in, a better person. But I really don’t know.

When I consider all that happened, was this the ultimate nightmare I had to experience in order to evolve, even a little bit, from the man I was? Or is it always the penultimate lesson to be learned? Always the next to last? There’s a quote from the Greek poet Aeschylus. I first found it many years ago, reading a biography of Robert Kennedy. The passage came to have so much meaning to him after the assassination of his brother, that he jotted down the lines on a scrap of paper and kept it with him every day. He was able to read it to a crowd of supporters on the night Martin Luther King was murdered in Memphis, in April 1968. It was in his pocket when he was shot to death eight weeks later.

I looked for that poem recently. Then I realized I had memorized it years ago, and somehow, somewhere in the recesses of my brain, it was still there…

“He who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep, pain that will not forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, until in our despair, against our will, comes Wisdom by the awful grace of God.”

But then I wonder if it’s even true. Another wise man once said, “The only thing we learn from history is that we do not learn.” Though so much of my pain was self-inflicted, the remedies I sought seemed to make things worse. If I am wiser than before, I fear it’s only incrementally so. Do any of us ever really learn anything from our stumbles and falls? And if it’s possible to learn from one’s mistakes, and be a better man for the ones we love the most, does it come too late to matter? I feel like the atheist at his own funeral—“all dressed up and nowhere to go.”

But then should any of us expect a reward for our efforts to be better people? Wouldn’t that diminish the sincerity and integrity and honesty of the effort? Ultimately, I can only hope that all this happened for some reason, even if it is beyond my ability, as a floundering and flawed human being, to ever fully understand.

Jim Stiles is the founding publisher and editor of The Zephyr, since 1989. (cczephyr@gmail.com)

NOTE: As you just read, my phone was confiscated at the Unit when I arrived, so I was unable to take any photographs. However, I found images online that the parent corporate hospital had posted, to celebrate a nearly half million dollar renovation of the Unit. Based on my own observations and from what the nurses told me, most of the “improvements” must have gone into reinforcing and fortifying the nurses station, an enclosed glass walled office that floated in the middle of the big room. I have no doubt that they have security concerns. But the improvements were not for the patients; they were for the protection of the staff. There were very few improvements that could have been made otherwise, other than re-paint a blank wall,..JS

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. WE GREATLY APPRECIATE YOUR INPUT & ANY ADDITIONAL INFORMATION YOU CAN ADD TO THE STORY…THANKS—Jim Stiles

You can still “like” individual posts. Why they can’t just

leave the site alone is beyond me, but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our amazing historic photo collections, be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

ONCE AGAIN, TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. I’D GREATLY APPRECIATE YOUR INPUT & ANY ADDITIONAL INFORMATION YOU CAN ADD TO THE STORY… ESPECIALLY IF YOU’VE HAD SIMILAR EXPERIENCES WITH THE MENTAL HEALTH INDUSTRY. THANKS—Jim Stiles

:

Jim I just read your moving, dismaying piece. I am a psychiatrist who works in a hospital system (medical, not psychiatric) and treats patients with mental health concerns. Some have been placed on an involuntary mental health hold for a psychiatric condition, being at immediate risk of self harm, and/or having symptoms that require inpatient treatment. I suspect you were held under your state’s statute which may be equivalent. Substance abuse impairment is specifically excluded.

My role is to sort through the circumstances and determine if the person meets criteria. If not, they must be released. If so, they are transferred to a receiving facility. The involuntary hold has a time limit and following transfer a decision has to be made to extend it through a legal process. If not extended, the hold expires after which the patient may decide to stay voluntarily or, again, must be released.

I do not see how you met criteria for an involuntary hold. You were asking for help, not refusing care! You were not imminently self lethal! Is the substance abuse with which you were (mis)diagnosed exclusionary for your state? It is in mine. If you were in a detox unit, what detox protocol was followed? Seroquel and anxiety meds are utilized as you point out but are not typically detox agents. Patients cannot be coerced into taking any psychotropic medication. They must first sign a specific form (unless a behavioral emergency for which there is a different process). I have never heard of compulsory outpatient treatment as a condition for release. A magistrate or judge would have to order it. Just about the only time I have seen that is related to a legal charge which you did not have.

Your rights and autonomy are paramount.

As bad as your experience was, even worse to me is how it shapes your view of the mental health care system. I hope you find supportive treatment that not only makes you feel better but allows you to grow. You can! I assure you it exists as others have also shown. So many heartening replies. Thank you for sharing your story.

Jim, your writing about this event helped you ( I hope ). No other circumstance I know of would take away your right to making decisions for yourself. We are always encouraged to seek professional help if we feel any struggles with our mental health. All the events in your life at the time would certainly cause most of us to struggle with out mental health. I have gone through my adult life with no close friends, we work- and provide. I regret letting relationships with friends fall to the wayside. Even though I am still married-it is like my wife and I are living apart together ( yeah that’s a thing these days ) for convenience, or out of respect. Hope you get out and take walks daily-just putting one foot in front of the other and doing the best you can for that day. Volunteer work ( service to others ) would make you feel better. And you might meet some new people that could become friends. And those people could probably use a friend like you. It is working for my one close friend, who is providing live in care for his 95 year old father- and needed an outlet. I visit my 90 year old Mom weekly in her assisted living home. I don’t think ( with her dementia ) that she even knows who I am. I think her 20 years ( after my Dad’s death ) living alone ( at her insistence) contributed to her dementia. But, I could not live with myself if I didn’t see her weekly. I always hope every visit may give her some happiness. She too expresses not having a reason to live, and wanting to ” get out of ” where she is. Keep trying to find things in life to look forward to, Jim. It is all we can do. Being a single adult ( through divorce- death- single parents when kids leave the nest ) is a struggle, too. Thank you for sharing.

This is a very moving account. It is disgusting first, that any insurance company, let aline Medicare/Medicaid, would blindly support them. Second, I am so pleased your friend stood with you and you had a lawyer offering good advice. Cookoo’s nest is the only apt description. May you forge your path to peace and fulfillment.

Dear Jim,

I am so, so, sorry you went through this nightmare that only added to the problems you were experiencing. Thank you for sharing this horrific experience. I’m hoping that by doing so, you may prevent someone else from living through the same nightmare you experienced. Hopefully, telling about your ordeal has also been cathartic for you. I really enjoy the Zephyr and encourage you to keep writing and publishing it. You have come a long way, gained a lot of skills, and accomplished a lot since the breakup of your marriage. Your courage and talent are amazing! I see a bright future for you and The Blue Moon Zephyr!