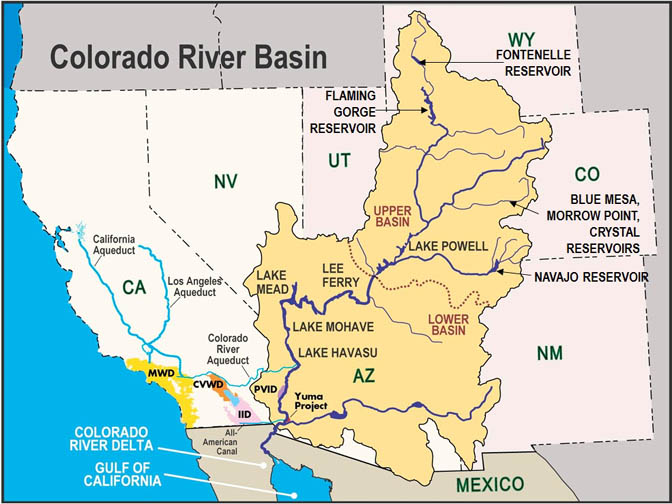

The river of menace and destruction… In the early 20th century, that’s the way farmers in the Imperial Valley of California viewed the Colorado River after it breached its banks and flooded into the Salton Sink in 1905-07. This wasn’t the first time the mighty river had jumped its banks, but the agriculture industry was determined this HAD to be the last. And it was – maybe. I’m not going to rehash how the Colorado River Compact of 1922 came to be passed by a bunch of politicians who gathered together in some isolated resort lodge near Santa Fe, New Mexico. But one key player is seldom mentioned when the history of the grossly inaccurate Compact is discussed. Or the devastating effect it poses on the future of the Colorado River Basin. His name was Eugene Clyde LaRue.

Even though erroneous assumptions were made and compiled in various tables, E.C. LaRue knew the Colorado River better than almost anyone, and was the most experienced engineer, even if his goals for the river were as wrongheaded as everyone else. He had personally surveyed just about every tributary and segments of main stems of the entire Colorado River Drainage Basin. Why did his compatriots give him a place at the table? Who was this guy anyway?

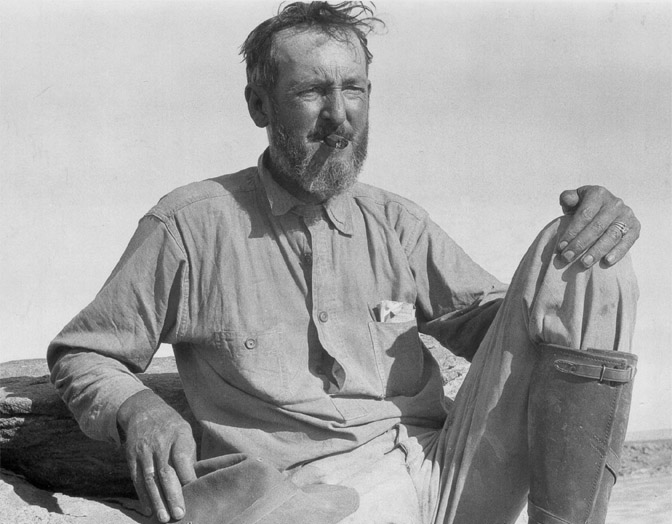

Eugene Clyde LaRue (1879-1947) received his BS Degree in Engineering from U of Cal in 1904 and began working for the Bureau of Reclamation to “promote economic development” of the western United States. The newly established bureau was originally established under the USGS in 1902, but in 1907 the Secretary of Interior separated USGS from the Reclamation Service and formed an independent bureau within the Interior Department.

LaRue began work as a junior engineer and was promoted to senior engineer in 1910. He did what he was good at. He investigated sites for potential dams, did the calculations and recommended the best sites, regardless of what would be flooded by this madman. He worked out of the Great Basin District in Salt Lake City until 1911 and then moved to Pasadena, California where he remained with the USGS until 1927. The BurRec/USGS surely found their man, because he mapped out just about every possible spot in the entire Colorado River drainage basin to place a dam. He was obsessed with building dams..

However, irrigation of the Imperial Valley and supplying southern California with water was, by far, the foremost objective in controlling the raging Colorado River. Nathan C. Grover said as much in his Introduction to LaRue’s 1916 Water Supply Paper: “Mr. LaRue has attempted the pioneer work of assembling the principal facts relating to the subject, and especially of studying the possibility of controlling the flow of the whole river by means of storage reservoirs in order to avoid further danger of overflow to the Salton Sink and to render available for profitable use the enormous quantity of water which now flows unused and largely unusable to the Gulf of California in the form of flood water.”

“The Colorado River – river of menace & destruction,” was repeated frequently by Secretaries of Interior Hubert Work and Nathan C. Grover in forewords to E.C. LaRue’s reports of 1916, 1925 regarding water power and flood control of the Colorado River. The Bureau of Reclamation has maintained that mantra to this very day.

Secretary Work insisted that the “most urgent needs of development relate to flood control, in order that lives and property of the lower river may not be subjected to the annual menace of destruction” [emphasis added]. The BurRec thought that when favorable dam sites had been identified and built, this great river would become a manageable and productive national resource. Besides ensuring controlled irrigation flows into the Imperial Valley, it would also continue to supply a reliable amount of water to the growing metropolis of Los Angeles. None of them could have imagined how much LA, and the rest of the arid Southwest would grow.

Note: Imperial Valley aka the ‘Salton Sink’; the dams were planned so that the 233-mile-long Los Angeles Aqueduct (completed in November, 1913) while William Mulholland (1855-1935) was head of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

A MAN WHO LIVED FOR DAMS

Two USGS Water Supply Reports by E.C. LaRue (#395 published in 1916 and #556, published in 1925) provided summaries of his work involved with flood control and storage, including the Colorado River and its watershed from Wyoming to the Gulf of California delta. He was passionate about his work — LaRue calculated the required heights of dams, the volumetrics of water stored, evaporation rates, etc. He researched sites for potential dams with historical information on floods in the area, precipitation records, stream flows— he sought any relevant data he could get his hands on for controlling water flow and preventing flooding and “waste.” He strongly believed in conserving water which meant storing it and controlling it so that it could be used for human activities. Like almost all of his colleagues, natural resources were here to serve the needs of humanity. Water that reached the sea was considered a “waste”. And though he also recognized the voluminous quantities of sediment that was carried by high gradient streams, his calculations were grossly underestimated.

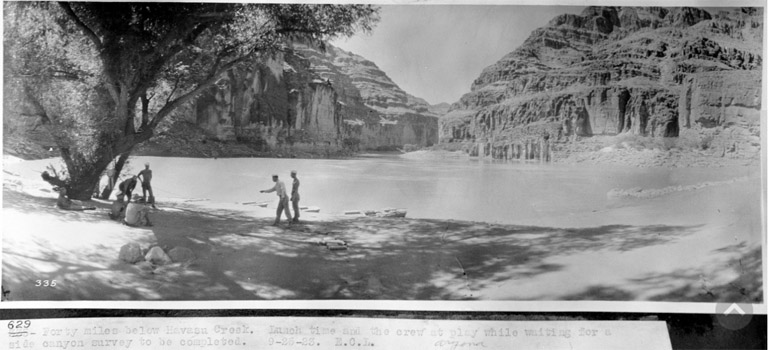

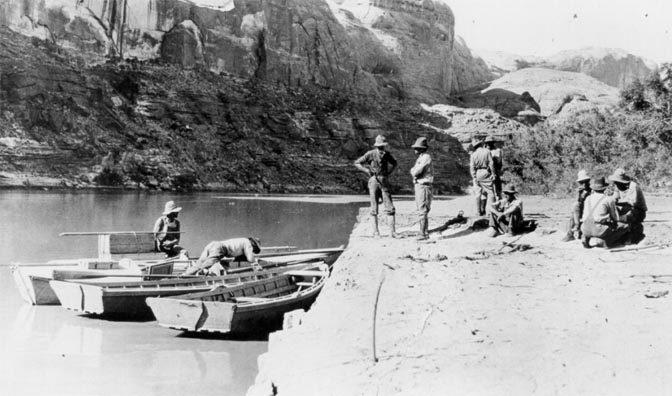

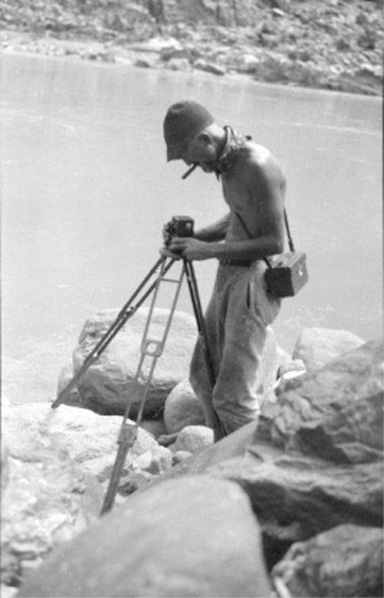

From 1914 to 1921 LaRue made numerous river trips, (both down river and upruns) for nearly every boatable segment of the Green from Green River, Wyoming to the confluence in Cataract Canyon. to Moab, Utah. In 1922 he traveled downriver from Green River, Utah through Cataract Canyon and Glen Canyon to Lees Ferry, Arizona. But his year wasn’t done—also, in 1922, he boated from Boulder Canyon to Yuma, Arizona. The following year, he was back again; in 1923 he ran the river from Lees Ferry, through the Grand Canyon, and finally to Needles, California.

Although he participated in these numerous river trips, E.C. LaRue is probably best known for his role in the Birdseye Expedition through the Grand Canyon in 1923. This expedition was launched to survey the remainder of the river which had not yet been accurately surveyed. This 251-mile stretch of the Colorado ran through the Grand Canyon from Lees Ferry to Diamond Creek.

However, as a Bluff resident and longtime San Juan River observer/river runner, it’s ironic that in all his treks down rivers, he never set foot into the canyons of the San Juan River, the largest perennial tributary to the Colorado River below the Green-Colorado confluence. Instead, he relied on measurements made by R.C. Pierce (1916, USGS WSP #400) who also grossly underestimated both the flow and sediment content of this major tributary.

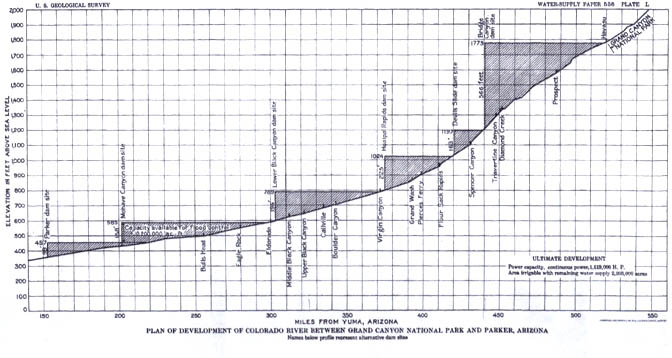

The purpose of La Rue’s synopsis was to provide data for dam sites between Cataract Canyon and Parker, Arizona, and to provide “a comprehensive plan of development” of a contemplated 13 dams. His plan would create 3,383 feet of head for the development of power and a maximum of 42,000,000 acre-feet of storage capacity for the control of floods, equalization of flow, and storage of silt.” His proposal failed to include the innumerable proposed smaller dams scattered throughout Grand Canyon National Park.

“GUESTIMATING” GAGES

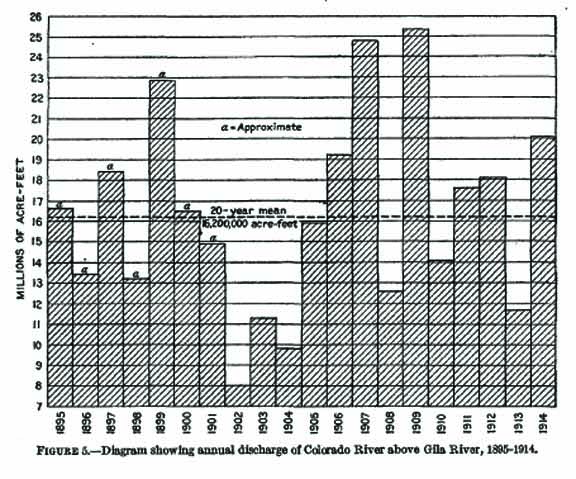

Information from gaging stations maintained by the USGS and arranged in downstream order along the main stems and tributaries, were used bt LaRue to support his proposals. Data was collected from 1891 to 1915, but was far from reliable — most stations were only operational for single years, or a limited few. Many gages were flooded and never replaced. The oldest continuous operational gage was on the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona. It provided records as far back as 1891, when LaRue compiled report data. Many other gages ended operations in 1911 (after the big flood). The water gages on the Upper Colorado, Green, Yampa, Gunnison, most of Uncompahgre, Dolores, Muddy, and most tributaries to upper San Juan including Animas, La Plata and Mancos were sporadically operational (1904-1915, but at 1-to-2-year periods).

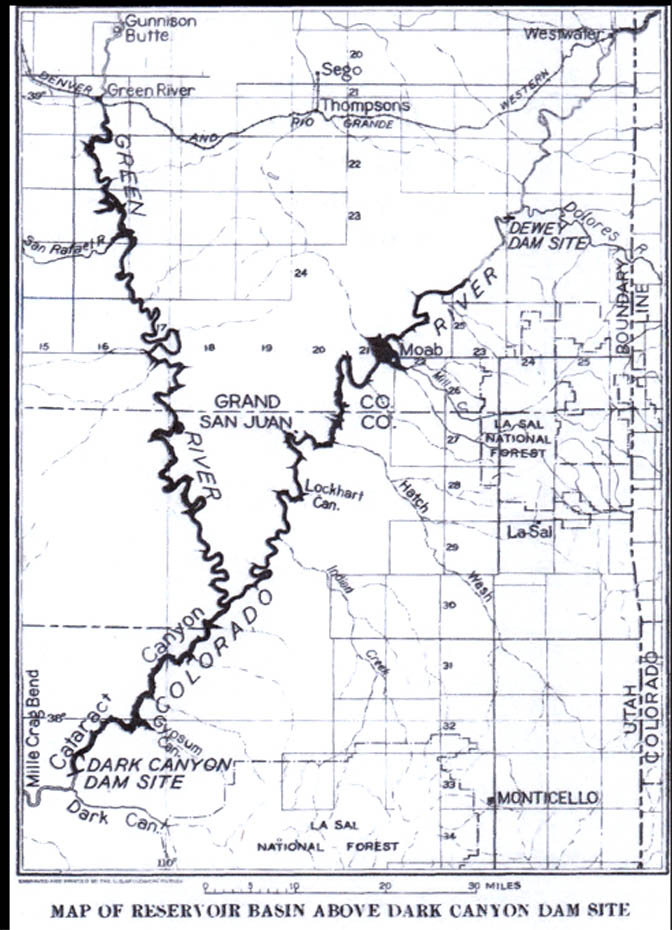

LaRue noted that the middle section of the Colorado drainage basin was probably the most remote and inaccessible region in the conterminous USA. From the mouth of the Green River confluence with the Colorado above Cataract Canyon, to Grand Wash cliffs —- a distance of nearly 500 miles — there were only three locations where the river could be reached “with a wheeled vehicle.” Because of this inaccessibility and the absence of inhabitants in the region, no stream-gaging stations were established until years after his reports. (Map of reservoir basin above Dark Canyon dam site)

Between 1921 and 1923, the USGS & So. Cal Edison Co. established a gaging station at Lees Ferry and at the mouth of Bright Angel Creek in the Grand Canyon. Since these were so new, he still depended on stats from the Yuma gage, where there were continuous records since 1902; LaRue mentioned evaporation losses especially from Yuma to Pierces Ferry; but it was impossible to calculate the amount of water lost. Therefore, he suggested a more accurate flow estimate could be obtained from main-stem and tributaries in the upper basin. But the lowest gage on the Colorado River was at Fruita, Colorado, above the mouth of the Dolores River. Various new gages, that were also maintained and monitored, but not regularly, were established at Cisco, Moab, along the Green River at Little Valley , and the San Rafael River, They were monitored at various times between 1908 and 1923.

Other tributaries below the confluence of Green & Colorado Rivers and Lees Ferry included the Fremont, Escalante and San Juan Rivers. Gages on Fremont 1909-1914 (avg annual discharge of 200,000 ac-ft) led LaRue to assume that outflow from the Escalante River would be similar. Pierce’s (1916) estimate of 2.5 maf/year was used for the San Juan River.

LaRue’s final tally from 1911 to 1923 concluded that the annual discharge estimates at Lees ranged from 10.48 million acre feet (maf) per year in 1919 to a high of 20.47 maf/year in 1917.

LaRue summarized his best guess estimate (guestimate) of the water supply available in 1922 stating that it was based on highly variable and scattered gaging points throughout the Colorado River Drainage Basin. He stated that the 13-year period 1911-1923 did not include low-flow years of 1900-1905 and that the 1911-23 years were higher than the 29-year average if flows from 1895 to 1923 were factored in.

He somehow assumed no loss of water in transportation, but suggested a 20% loss due to evaporation or water just “wasted” by improper regulation. And because the storage areas would be hundreds of miles above lands to be irrigated, then it would be necessary to “deliver more water than actually required in order to avoid” any shortage. Therefore, he foresaw that an aggregate amount of 18 maf of water would be needed to meet its requirements to lands below the mouth of the Virgin River, and to make up for low-flow years like 1902 to 1905. And to meet those needs LaRue suggested that the best reservoir sites were on the upper Colorado and its tributaries.

LaRUE’S GLEN CANYON DAM DREAM

LaRue wanted in the worst way for Glen Canyon Dam to be built before Boulder Dam as he envisioned a gravity fed aqueduct to be built to supply water to the lower elevation desert communities of Phoenix and Tucson. His desires were overruled at the time, however, by 1994 a 336 mile-long Central Arizona Project (CAP) diversion canal system had been completed across central and southern Arizona.

Rather than following LaRue’s suggestion of natural gravity to move water from higher elevation to lower, the CAP system diverts water south of Lake Havasu near Parker, AZ where 1.4-million-acre feet of water is lifted 2,900 feet by using 14 pumps requiring 2.5 million MWh of electricity per year, thus making it the largest power user in Arizona. Additionally, the canal loses approximately 16,000 acre-feet of water each year to evaporation. It also loses approximately 9,000 acre-feet annually from water seeping or leaking through the concrete.

Furthermore, even though LaRue and the “Silbert Board” report had lower averages [the Silbert report was totally dismissed by Hoover], Herbert Hoover and the boys from the seven western states along with the Washington, D.C. bureaucrats went about cherry-picking intervals of high-water years to come up with the magical 15 million ac-ft per year number that was politically agreed upon for the Colorado River Compact in 1922.

Throughout 1924 and 1925, LaRue continued to advocate for the first large dam to be built near Lees Ferry and was vociferously against the Boulder or Black Canyon site. He was acerbic and sanctimonious in his views and presented them wherever he could. In 1924 he presented his views to a Senate Committee on the Development of the Colorado River. He considered the controversial Boulder Dam a waste of taxpayers’ money and a waste of river water primarily due to the expected evaporation from the large surface area of the resulting reservoir. He felt that building the dam at sufficient height to produce power in order to pay for the construction was not in the best interests of anyone. In his papers and articles, he presented a good case in support of his ideas.

For years he promoted his plan for control of the Colorado River and adamantly insisted on a dam near Lees Ferry in spite of the ‘official’ emphasis on Boulder or Black Canyon for the main control structure. LaRue maintained that the alleged available amount of water was based on recent higher precipitation rates, and that it was vastly overestimated. His superiors were not pleased. In June of 1926 LaRue received a telegram from the Director of the USGS; they ordered him to keep quiet because his views contradicted adopted policy. LaRue called this his “muzzle telegram.”

Finally, in 1927, he resigned from the USGS and went into partnership with B. F. Jakobsen as consulting engineers, based out of Los Angeles. Both Jakobsen and LaRue continued to offer their professional advice regarding the control and use of the Colorado River, as well as other engineering and water control projects. In the late 1920s they were involved in the controversy over the siting of an aqueduct to carry Colorado River water to the Los Angeles area.

As proponents of a dam site at Bridge Canyon, they believed that a better and cheaper dam could be built than at Boulder (or Black Canyon). The dam site they proposed would store more water and could deliver water to the Lower Basin states, using gravity flow and a minimum of pumping. Again, LaRue fought the political system that continued to favor Boulder Dam. Ultimately that location (now Hoover Dam) was authorized by Congress in 1928. Jakobsen and LaRue dissolved their partnership in 1933.

Eventually, E.C. LaRue went to work for the Army Corp of Engineers in Los Angeles. He worked with the Los Angeles Flood Control District until his death in February 1947.

AFTERMATH

Instead of 13 dams across the Colorado River Drainage Basin, as E.C. LaRue dreamed of, nine were eventually built, including Hoover Dam, which was completed 1936, and in 1963, Glen Canyon Dam . Neither dam was located where LaRue wanted. His concept of gravity fed aqueducts from Glen Canyon never happened. He was correct in his warning that annual discharge rates past Lees Ferry were overly optimistic, but he had no idea what a 30-year, or longer, extended drought could do to a region that continued to grow in population that now exceeds 40 million users, as well as continued agricultural use.

And LaRue, as well as others, horribly miscalculated the voluminous amount of silt and sediment that the Colorado River system carried and deposited in each dammed reservoir. After all, LaRue was a Reclamation engineer that worshiped at the altar of technology. Conversely, the earth sciences longer-termed holistic analysis failed to demonstrate that impounding high gradient, silt-laden streams wildly ranged in their seasonal and annual supplies of water, and could not be controlled with dams. Dams built on muddy rivers were short term solutions to long term problems.

The State governors from the seven Colorado River Basin states were complacently blinded by the BurRecs promise to “promote economic development;’ the only assumed beneficiaries were the farmers in the Imperial Valley, or Los Angeles residents who would receive water via the aqueduct. Note that both Havasu and Mohave reservoirs remain full, to accommodate the original users, while the larger reservoirs upstream continue to drop precipitously to “dead pool” elevations.

They ignored the relatively short time that these dammed reservoirs were capable of providing water, and electricity, to an exploding population across the entire western U.S. And they certainly didn’t take into consideration that much of the basins’ water would be siphoned across the Continental Divide to places like metro-Denver, or Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

Nor did they ever contemplate that Phoenix, Tucson and Las Vegas would grow exponentially, or that Native American tribes would dare ask for what had been promised to them, or to honor the agreement with Mexico to keep water flowing to the Gulf of California. And yet, even today, more and more diversions are being proposed for this over-subscribed river system.

John Wesley Powell said it first, later articulated by Wallace Stegner about limiting human settlements west of the 100th Meridian. Now, 100 years after the signing of the Colorado River Compact, it is time to have a new meeting of the governors, and Federal bureaucrats, and this time, the public at large should be included in the discussion and face reality. The

“menace” isn’t the river, or climate change; it’s simply that too many humans have moved to

arid lands that would never support the population and consumption explosion that has and is devastating the American Southwest.

It’s important to remember, with all our technology and engineering skills — Mother Nature Always Bats Last.

POSTSCRIPT

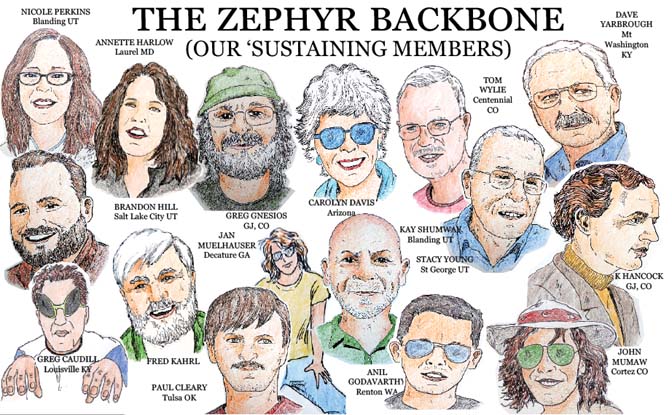

When I read Jim Stiles “America’s Insane…” paper last in the Canyon Country Zephyr where he listed 1950 census numbers, I thought it might be of interest to list population numbers of 1910, 1915, when water studies resulting in the 1922 CRC were in progress – just about 100 years ago. WOW, how populations have changed! Water availability and floods and silt, etc was all about irrigation of the Imperial Valley, with far, far fewer people relying on Colorado River water.

An estimate of the population of the Colorado River basin in 1915 & 2021, including a a list of the principal cities, then and now…

Estimated population in Colorado River basin, 1915 and in 2021

Arizona………………….. 200,000 7,276,316

Colorado…………………. 127,000 560,291

Utah…………………………. 47,000 459,631

New Mexico……………… 44,000 252,967

Wyoming………………….. 30,000 91,099

Nevada…………………… 7,000 2,297,001

California………………… 2,000 103,900 (but a much larger population extracts water from the river)

Mexico…………………… 75 At least a million

Population of important cities in Colorado River basin, 1910 vs 2010 [source: Wikipedia]

Tucson, Ariz………………… 13,195…………….42,629 Pima Co.

Phoenix, Ariz………………. 11,134 ……………..1,608,139 Maricopa Co.

Grand Junction, Colo……… 7,754 ……………..65,560 Mesa Co.

Globe, Ariz……………………. 7,083 ……………..7,532 Gila Co.

Rock Springs, Wyo……….. 5,778 ……………..23,036 Sweetwater Co.

Prescott, Ariz………………. 5,092 ………………45,827 Yavapai Co.

Morenci, Ariz……………… 5,010 ………………..1,500+/- Freeport-McMoRan Copper largest in No. Am.

Clifton, Ariz………………… 4,874 ………………..3,700+/- copper town; Greenlee Co. seat

Durango, Colo……………… 4,686 ………………55,638 (metro) La Plata Co.

Nogales, Ariz………………. 3, 514 ……………….1,027,683 (Santa Cruz Co., USA + Nogales, Sonora)

Yuma, Ariz……………….. 2, 914 ………………….93,064 Yuma Co.

Lowell, Ariz……………….. 2, 500 …………………5,575 Cochise Co. (combined w/Bisbee)

Jerome, Ariz……………….. 2,394 …………………444 Yavapai Co. (>10,000 in 1929s mining boom)

Winslow, Ariz……………… 2,381 ………………….9,655 Navajo Co.

Gallup, N. Mex…………….. 2,204 …………………21,899 McKinley Co.

Silverton, Colo……………… 2,153 ………………..637 San Juan Co.

Glenwood Springs, Colo… 2,019 ……………….9,614 Garfield Co. (metro 79,043)

Telluride, Colo…………….. 1,756 …………………2,325 San Miguel Co.

St. George, Utah…………. 1, 737 ………………..72,897 Washington Co. (2020 pop= 95,342)

Ouray, Colo………………… 1,644 …………………..1,000 Ouray Co.

Green River, Wyo…………. 1,313 ………………….12,515 Sweetwater Co.

Las Vegas, Nev…………….. 1,275 ………………….583,756 Clark Co. (2020 pop= 641,903; 1910 pop 800)

Steamboat Springs, Colo.. 1,227 ………………….12,088 Routt Co.

Gunnison, Colo…………….. 1,026 …………………..5,854 Gunnison, Co.

Price, Utah………………… 1,021 ……………………..8,715 Carbon Co.

Fruita, Colo……………….. 881 ……………………….12,646 Mesa Co.

Kemmerer, Wyo……………. 843 …………………….2,656 Lincoln Co.

Los Angeles, CA …… 319,198…………………….. 3,792,621 L.A. County, CA

Palm Springs, CA incorporated in 1938 ……………44,552 Riverside Co., CA (In 2001 the 100th golf course was opened)

FACTOID

Three expeditions were amassed to explore the Colorado River region. Hernando de Alarcón sailed in May, 1540, to explore the region north of New Spain, and at last reached the head of the Sea of Cortez. Alarcón named it Rio de Buena Guia (good guidance), from the motto on the Viceroy Mendoza’s coat of arms. He said: “And it pleased God that after this sort we came to the very bottom of the bay, where we found a very mighty river, which ran with so great fury of a stream that we could hardly sail against it.” Here began the acquaintance of Europeans with the river later to be known as the Colorado of the West. Alarcón proceeded up the Colorado in small boats to a point about 100 miles above the mouth of the Gila River.

Melchior Diaz, in the fall of 1540, while attempting to contact Alarcón for Coronado, saw the lower part of the Colorado River and named it Rio del Tizon. He proceeded to explore the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers and surrounding country in the vicinity of the Chocolate Mountains. At about the same time (1542) Don Garcia López de Cárdenas reached the south rim of the Grand Canyon where they could see the Colorado River thousands of feet below. The canyons of the river, however, remained unexplored for 327 years thereafter until 1869.

RESERVOIR DATA: June 15, 2022 [day 261 of 365 for water year 2022; or 72% through the water year]

RESERVOIR NAME & ELEVATION

Location: Gunnison River, CO

Year built/completed: 1966M Blue Mesa: full pool: 7520.00’ 829,500 ac-ft, present level: 7461.78’

Percent of Full pool 45.59%

Location: Green River, WY/UT border:

Year built/completed: 1964M Flaming Gorge: full pool: 6040.00’ 3,788,900 ac-ft ,

present level: 6015.21’ Percent of Full pool 72.6%

Location: San Juan River, NM/CO border

Year Built/completed: 1963, Navajo Dam: full pool 6085.00’ 1,696,000 ac-ft

present level: 6028.11’, Percent of Full pool 55.5%

Location: Dolores River, CO

Year built/completed: 1984, McPhee Res: full pool: 6929.00’ 381,051 ac-ft

present level: 6889.89’ \ Percent of Full pool 65.01%

Location: Strawberry River, UT

Year built/completed: 1972, Strawberry Res: full pool: 7612.00’ 1,106,500 ac-ft

present level: 7588.22’, Percent of Full pool 79.04%

Location: Colorado River, AZ/UT border

Year built/completed: 1963, Lake Powell: full pool 3,700.00’ 24,322,000 ac-ft

present level: 3537.18’M Percent of Full pool 27.56%

NPS update on ramps: 13 ramps listed as “unusable, go to main marinas.” Lake level ranges from 13.82’ to 142.82’ below absolute minimum lake level

Location: Colorado River, NV/AZ border

Year built/completed: 1936, Lake Mead: full pool 1219.60’ 25,877,000 ac-ft. present level: 1044.56’

Percent of Full pool 28.19%

NPS: No data available for marinas or ramps

Location: Colorado River, NV/AZ border

Year built/completed: 1951, Lake Mohave: full pool 647.00’ 1,809,800 ac-ft, present level: 644.16’

Percent of Full pool 95.62%

NPS: No data available for marinas or ramps

Location: Colorado River, AZ/CA border

Parker Dam: Year built/completed: 1934-1938, Lake Havasu: full pool 450.00’ 619,400 ac-ft, present level: 448.76’

Percent of Full pool 96.03%

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE:

THE ZEPHYR BLUE MOON EXTRA’S MOST READ RECENT POSTS

“GRIEF MEETS ORWELL & THE CUCKOO’S NEST

(My Recent Encounter with the Mental Health Industry)

—by Jim Stiles https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/08/07/grief-meets-orwell-the-cuckoos-nest-by-jim-stiles-my-recent-encounter-with-the-mental-health-industry-zx20/

By Bill Davis

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/06/26/my-pelvis-and-its-place-in-the-universe-bill-davis-zx14/

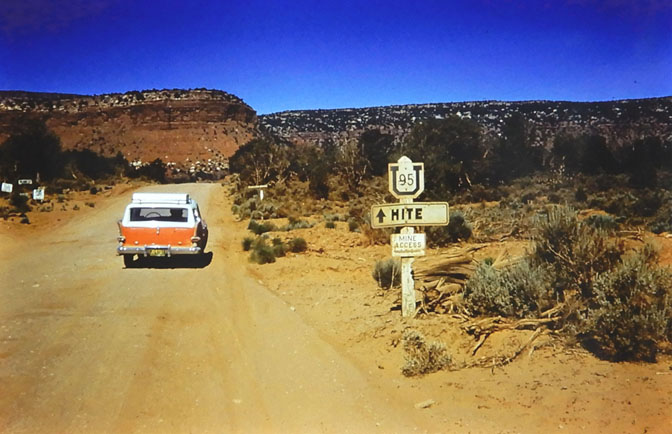

(1959-1963

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/07/10/ut-hwy-95-the-road-to-glen-canyon-hite-ferry-w-edna-fridley-charles-kreischer-1959-62-zx16/

Very revealing history of past people and influences that have resulted in current difficulties affecting the Southwest today. Thanks for this interesting account of past unfortunate actions that have caused tragic problems for the environment and water supply today.

( a … big … sigh) — i’ve lived within 2 miles of the colorawdough river (grandjunxion area) for over 40 years. and yet have no sense of “knowing” the critter. however, your detailed story does an excellent job detailing all the over-expectations, the over-(gu)estimations, all the “over-over”s which probably will not, in my lifetime, have any hope of a happy nor reasonable resolution.

Forgive their sins for they knew not what TF they were doing.

https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/science-be-dammed

Here’s an entire book about LaRue and how the dam builders ignored his numbers. It’s a little dry (much like the river itself), but is a fascinating read for the curious and the concerned. This article certainly does the story justice.

[…] much closer to the long-term reality were parallel analyses from U.S. Geological Survey scientist Eugene Clyde (E.C.) LaRue, which relied on limited data and proxies from the drier decades of the late 1880s. His work […]