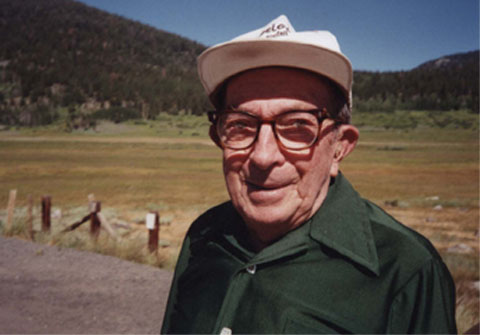

NOTE: I’m posting this in the late afternoon of December 11. Herb Ringer died 24 years ago today. I have shared his pictures and stories for the entire life of this publication. And I’ve written a few stories myself about my dear friend. This story combines parts of past stories and introduces some new ones as well. And more pictures, of course. He is still missed after a quarter of a century, especially by me—JS

*****

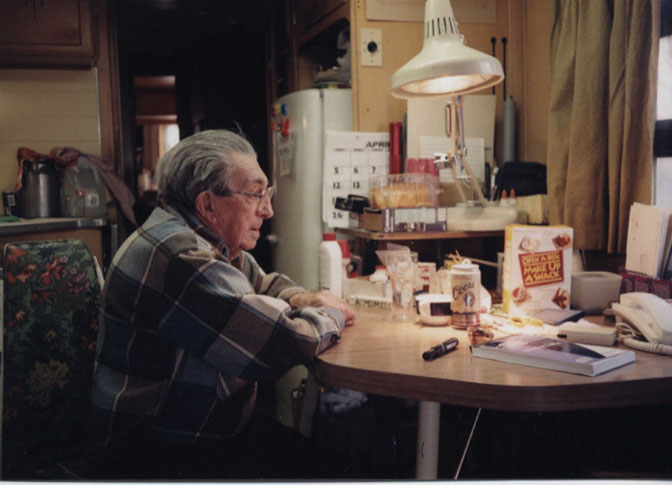

February 1997. A gray morning in Fallon, Nevada. “Let me show you something.”

Herb Ringer paused for a moment, then pushed his chair slowly away from the table and stood up. He turned and walked down the darkened hallway to the bedroom of his trailer, the same travel trailer he has lived in since 1954.

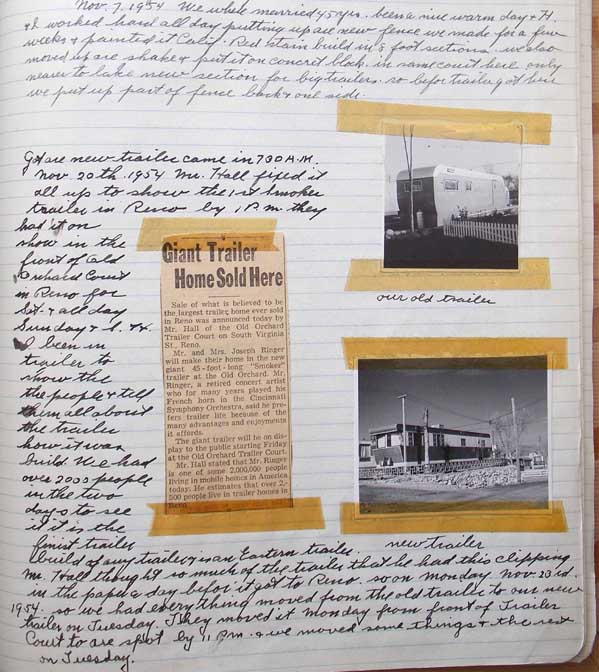

On November 21st of that year, the local Reno, Nevada newspaper reported:

GIANT TRAILER HOME SOLD HERE.

Sale of what is believed to be the largest trailer home ever sold in Reno was announced today by Mr. Hall of the Old Orchard Trailer Court on South Virginia St. Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Ringer and son Herbert will make their home in the new giant 45 foot “Smoker” trailer at the Old Orchard…The giant trailer will be on display to the public starting Friday.

It was quite an event. Herb saved the clipping, now faded and yellow, and tucked it away with a few thousand other tokens and artifacts of memories that document his life, an adventure now almost 85 years long. Each of those tokens is a story and all one has to do is wave the memento beneath Herb’s nose and everything comes back, in extraordinary detail. He looks at a photo and he remembers the date it was taken, the place and the people who were there. But he also remembers the smell of it, the angle of the light, the warmth of the breeze…the feeling of that moment. He wraps himself in the memory and the glow of it warms us both.

THE CRYSTAL-CLEAR VISION OF A CENTURY

His mind is as clear and crisp as the Rocky Mountain streams he spent summers by in years past. But his body is failing him. As I watched Herb disappear into his darkened bed room, I knew he was making his way there by memory as well. His eyesight has deteriorated to the point where he can’t even see the vast collection of photographs he took of his favorite places over the last half a century. But he can still enjoy them.

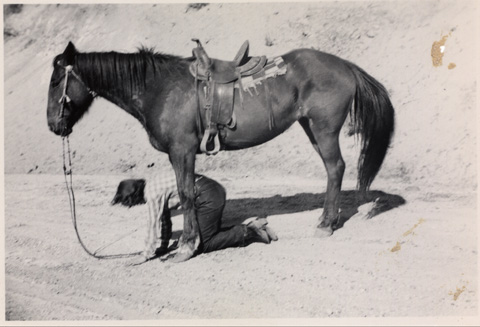

“Herb,” I’ll ask, “Here’s a picture of you on horseback and in the next picture there’s a girl on her hands and knees under her horse. What’s that all about?”

His worn out eyes sparkle.

“Yes!” he smiles, “That’s Skippy. That was in the High Sierras in about 1942. She loved her horse and the horse would do anything for her. She bet me she could sit right under it and I didn’t believe her. So she climbed down and crawled right under the horse’s front legs. So, I took a picture. And that night I bought her a steak dinner.”

I could hear Herb moving things about in his closet and a few moments later he emerged from the bed room, a manila-covered album held tenderly in his hands. He returned to his chair, a bit winded from the short trip, and then he placed the large book in my lap. It was the size and shape of a photo album but was covered with brown wrapping paper and held together with yellowed Scotch tape. I opened the binding to the first page. In block letters it read:

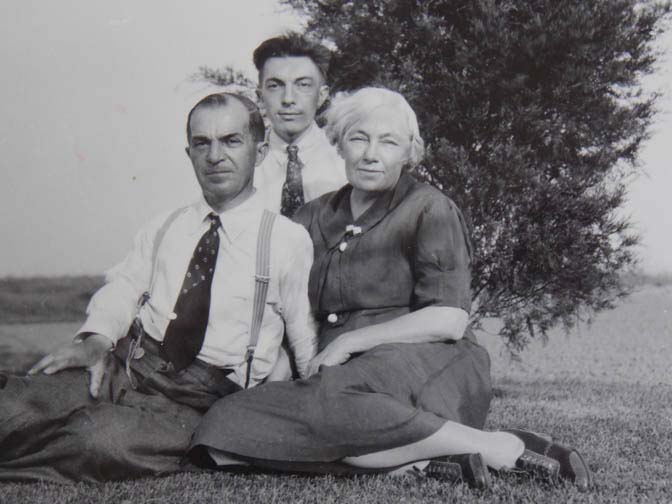

1944 RENO, NEVADA STARTED ON XMAS EVE

GIVEN TO ME AS A GIFT THIS BOOK BY MY SON HERBERT.

“This was my father’s journal,” Herb explained. “I gave the blank book to him a couple of years after I moved my mother and him out here to Nevada from New Jersey. He kept it going until just a few months before his death in 1963. Now my eyes are so bad I can’t even read from it any more…Would you read a few of the entries for me?”

I carefully thumbed through the hundreds of handwritten pages; Herb’s father painstakingly recorded the events of their lives with a fountain pen and supplemented the text from time to time with old black and white photographs, newspaper clippings and telegrams.

“Well Herb,” I said, “Why don’t I start at the beginning?” Here’s your father’s first entry…

Christmas Day Dec. 25th 1944

We are in Reno, Nevada and it is our second Xmas here. We lived at 988 Watts Street and I have been working at the Washoe Market with Herb. Herb took us on a trip this day . We left Xmas Eve and got home tonight as we had two days off from the store. We left at 7 a.m. for Winnemucca and got there at 3 p.m. We took a hotel overnight so we walked around town and after supper went to the movies. We had a swell time.

“Yes,” Herb nodded. “I remember that day so well. That was such a long time ago.” He looked at me and strained to see the outline of my face and he smiled again. “It’s even been a long time since we became friends hasn’t it?”

I nodded. “Where have the years gone, Herb?”

A CHANCE ENCOUNTER WITH A REMARKABLE MAN

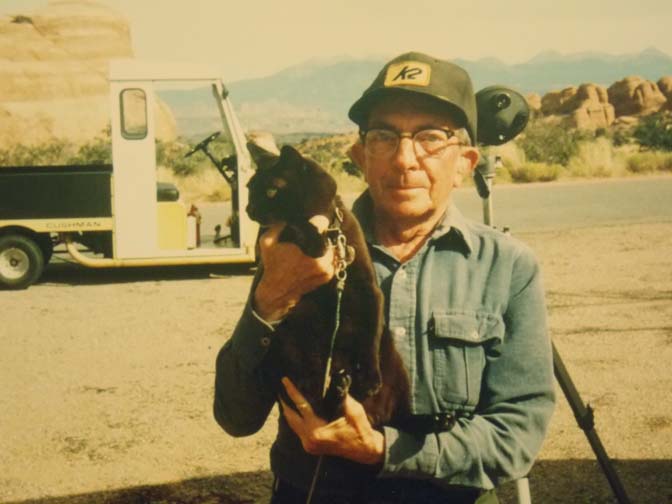

I met Herb Ringer in the early autumn of 1981 when I was a seasonal ranger at Arches National Park. In the evenings we used to walk the Devils Garden Campground to collect fees and to say hello. I found fee collection to be a tedious task most of the time, but the opportunity to occasionally meet someone special while making the rounds kept me hopeful. It was like that with Herb.

From the first evening, I found myself fascinated by his stories of the West and the passion with which he told them. After several days we traded a few details of our personal lives. I was enduring the aftermath of a divorce (#1) that summer and when he asked me if I were married, I gave Herb the two minute version of the ordeal.

Herb placed his hand on my shoulder and nodded empathetically. “Yes,” he said. “I know…I know what you’re going through. I was married once…”

His eyes drifted away from me as he remembered and talked and it appeared as though his gaze had settled on the distant La Sal Mountains. But I had the feeling his stare was cutting through the haze of time, not miles.

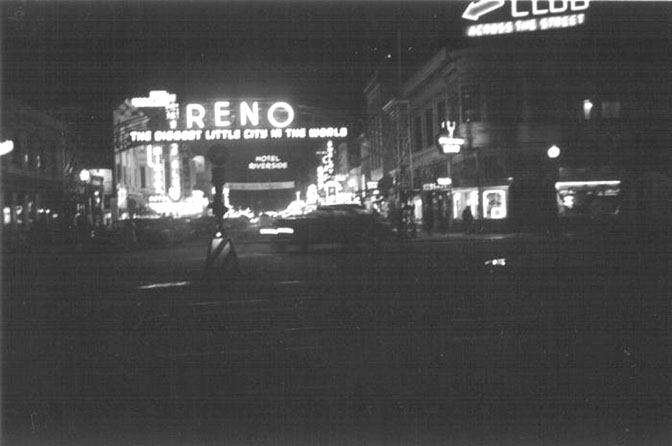

“…1938. I was married for a short time to a local girl. I traveled all the way to Reno, Nevada from New Jersey and got a divorce.”

His eyes welled with tears. “Oh I loved her…I still love her, I guess.”

I looked at this man, still staggered by a sense of loss, more than 40 years after his marriage failed, and I selfishly thought to myself, am I going to still feel this bad in another 40 years? The prospect of it made me shudder. But from that moment, Herb and I became kindred spirits.

HEARTBREAK AND A NEW LIFE

Herb told me about his marriage. He had met Marion several years earlier and were married on October 25, 1938. “She was beautiful…a beautiful girl.” They honeymooned in New England. He took her to Radio City Music Hall…the opera. “But we just couldn’t hit it off right, and rather than destroy each other, I decided I would have to make the move to end it.”

The details are still painful for him to discuss; eight months after their wedding, on Memorial Day 1939, Herb left his home in Ringoes, New Jersey. He traveled in his 1936 Ford across America, to Reno, Nevada. In those days, Nevada was the only state in the country that had fairly liberal divorce requirements and Herb simply didn’t want to go through the painful and public process of a divorce in his own home town.

Marion followed him by train, all the way from the East Coast and found him in Reno. She pleaded with him for a second chance, and Herb agreed. They drove back to Ringoes the next week. They lived with Herb’s parents in Ringoes through the winter of 1939. But within months, it was clear to Herb that their marriage would never be happy, even if it lasted. So for the second time in early 1940, Herb drove his 1936 Ford across the country and back to the boarding house, the Midway Hotel, where he had stayed before.

After the divorce was finalized in Carson City, Herb returned to New Jersey. He had borrowed $1000 from his cousin Bob Ringer and Herb was determined to re-pay the loan. He worked at a grocery in Clemington, NJ and saved every penny.

In six months he was debt-free but something unexpected had happened to him during the five months he spent in Reno; now he found himself dreaming and day-dreaming of the West he had left behind. He had never seen such magnificent open country and now he realized he could not bear to live without it.

“I had the great urge to return to the Western Way of Life. And so I did.”

For the third time in two years, Herb loaded up the ’36 Ford sedan and headed West in the winter of 1941, just before Pearl Harbor. He would never return East to live again. “From then on,” he remembered, “I was a tourist when I visited New Jersey.” Herb set out to find work and make a home in this strange new land. He had learned the grocery business at a small store near Ringoes; it was Herb’s first job and he loved it. Always the gentle gentleman, even then, Herb remembers that “I enjoyed being able to help people. My parents always taught me to be courteous and polite but this allowed me to do something for others.” So he applied for a job at the Washoe Market at 143 N. Virginia Street in Reno. He would stay there for the next 18 years.

And Herb set out at once, albeit unconsciously, to document his new life. He failed to see the significance of it at the time. But Herb loved to take pictures and he loved to write down his impressions and memories. He never considered himself proficient at either, but his efforts prove otherwise. Over the next 40 years, Herb took almost 10,000 photographs of an American West that simply doesn’t exist anymore. And his journals fill dozens of spiral notebooks. For him, it was a simple but enjoyable exercise; even Herb could not dream or predict the changes that lay ahead. On his days off, he would wander the country near Reno, taking black and white photos and returning every evening to record his experiences. One of his journal entries is particularly remarkable; he had left Reno early on a Sunday morning to explore some old mining town. He was by himself all day and had no idea that during that peaceful afternoon, the entire world had changed. When he returned that evening, he could see the lights of Reno blazing. He saw crowds of people reading EXTRA! Newspapers. The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. It was December 7, 1941.Later he recorded the entire day in his journal

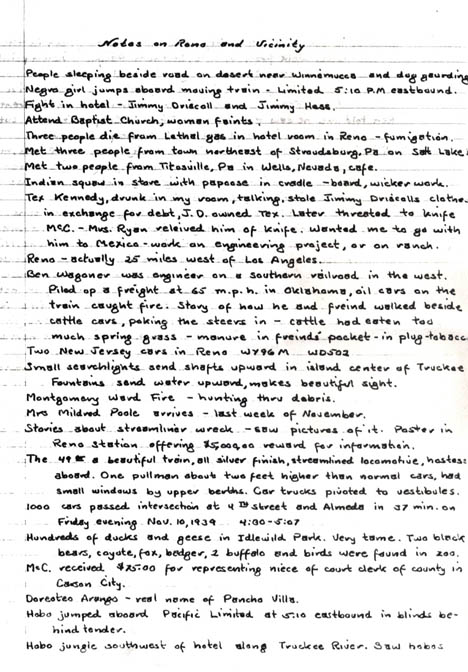

As he awaited his divorce to be finalized, he took up residence again at the MidWay Hotel. He kept a running list of “incidents” in a handwritten document called “Notes On Reno & Vicinity.” Here’s the first page and a link to the rest of them:

But while Herb basked in the excitement and adventure of this new home in Nevada and scribbled notes and took pictures, he could not forget his parents, who still lived in New Jersey. His mother and father had seen hard times during the Depression and now, practically penniless, they barely survived on the Ringer family’s farm in a small house they had built several years earlier.

I don’t know that I have ever met anyone whose devotion and loyalty and sense of responsibility to family was as strong as Herb Ringer’s. And so, two years after his own migration to Nevada, he returned east yet again and brought his mother and father back to Reno with him. “They did so much for me,” he once said. “Letting them stay with me for the remainder of their lives was the least I could do.” His memories of childhood are still vivid and sweet, but sometimes touched by a hint of sadness. Herb remembers the early days…

CHILDHOOD MEMORIES…

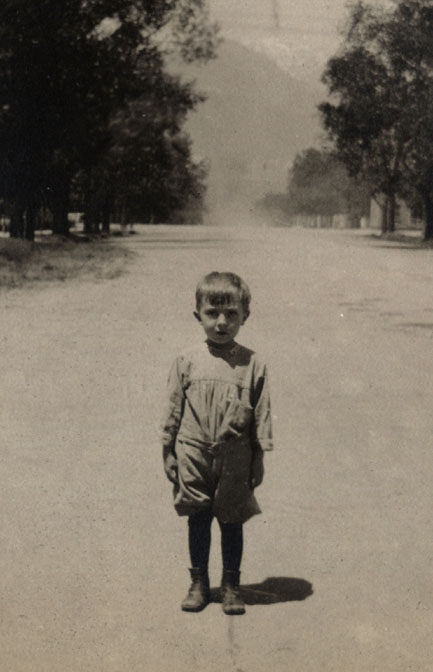

“I was born on July 15, 1913 in Brooklyn, New York at 80 Cornelius Street. We were living in my grandparents’ apartment while they traveled to Europe for a last visit. We moved to Cincinnati, Ohio not long after that. My father had a contract with the symphony starting in October. My father played French horn and my mother took care of me. I really don’t remember much until I was four, but that is where my life really began.

“When I was about four my father had an engagement to play the summer season out in Colorado Springs with a local band, the Colorado Midland Band, owned by the Colorado Midland Railroad. So we journeyed by train across the country to Colorado and my father rented a small cabin there. That cabin, by the way, stood until the 1980s when it was torn down for a new apartment complex. We spent a very enjoyable summer there. We loved the outdoors and we hiked every day. I remember they bought me a small red tin wagon which could be hauled quite easily to places like North and South Cheyenne Canyons.

“My father only had to play with the band in the evenings at the park so we had a lot of time to see many things. My mother and I sat on the grassy lawn and listened to the concerts each evening. We were there for most of the summer; then we’d return to Cincinnati and he’d play with the orchestra. I went to my first concert when I was five and I remember that with a shaking finger my father told me to be very quiet and not talk or rattle a paper or in any way disturb the other people who had come to enjoy the concert.

“We lived at 123 Mason Street in Mt. Auburn, a part of Cincinnati, but later the landlord bought a large three story building with a cupola on Auburn Avenue, and we moved into an apartment there. It had a huge living room about forty feet long and a bathroom and kitchen, and so we were safely ensconced there and enjoyed several years at that location. It had a large yard in back and it had a playground atmosphere where I could play. My father always brought me toys when he was on trips with the symphony. One particular set of toys was a set of little colorful Swiss buildings and I placed them around my train set. They lasted me for forty years.

“So I had many enjoyable days in that yard and I had the company of lots of squirrels who served as constant companions. But I didn’t have a lot of friends. I was a loner, even then. I learned to entertain myself quite well.

“That is partly due to my father, I suppose. He devoted his life to his French horn and practicing it to perfection and he didn’t want to be interrupted by screaming children. I could play in the house and I had toys to play with beyond measure but I had to handle them gently. That’s why they lasted me countless years. But I was pretty much alone. I didn’t have the knack of making friends.”

Herb came to know many of the orchestra members, including a musician named Ralph Cory, from Wachung New Jersey. Cory visited the Ringers on the occasion of Herb’s 11th birthday. Ralph presented Herb with a gift. Herb looked at the small piece of pottery and asked the same question I would pose 70 years later —”What is it?”

Ralph Cory replied, “It’s from King Tut’s Tomb.” Cory had traveled with an orchestra in Europe during the spring of 1924. He decided to take a side trip, across the Mediterranean Sea, to Egypt. It was the year that Tutankamen’s tomb was discovered. Archaeologists were hiring the local Egyptians by the hundreds as diggers. Many of them hid some of the smaller artifacts in their robes and sold them on the streets of Cairo. That was the story Ralph Cory told the Ringers on July 15, 1924, and the same tale Herb told me, so many decades later. Whether it’s really a relic of Tut’s tomb, who knows? But it’s a great story. It was an artifact that Herb kept on his kitchen table, in a small plastic jar, until he gave it to me a year before he died.

A year later, Herb’s life changed dramatically, and almost took his life. Herb remembered that—

“…When I was 12 I contracted rheumatic fever and it was treated much differently in those days. I had aspirations to follow in my father’s footsteps and be a musician but when I got sick the first thing they did was take me out of school and my musical aspirations ended entirely. It was thought that I should be kept as quiet as possible; sometimes they kept me in bed for six months at a time. And yet, I didn’t feel that badly…just tired I guess.

“And then, when I was 13 years old, we left Cincinnati forever, thanks to the murderous intent of the symphony conductor Fritz Reiner, who disliked all American musicians. He employed European musicians thinking they were better equipped to perform the great symphonic selections than their American counterparts. My father had already played 16 years with the symphony and it was a terrible defeat when he lost his position there. Up until the last three years, when Reiner arrived, he had loved his work, associating with all the great classical musicians of the world. So we moved back to New York.

“For a couple years, my father played with some of the large theater organizations. He played for the Lexington Opera House and for some movies. He played with many pit orchestras…he once played with Major Bowes of the Amateur Hour. He saw many good and many really poor performers on the stage. He often saw many of those poor performers ‘get the hook.’

“But he gave it all up, the thing he loved most—his music—for me, and we moved to the country to the family farm. They thought the country life, a quieter atmosphere would help my heart condition. And it did. It worked wonders. Soon I was able to run…run across the fields. Plus I was working daily on the farm.

“But my father had no way of making a living. No orchestras. No bands. Nothing. So we tried to make a living off the poultry we raised. But the price of poultry feed kept rising and we could not keep up.”

Herb learned that his mother and father were “destitute.” The farm had failed and they had been forced to sell the Ringoes home they had built themselves for just $3500.

And so Herb made the decision. “By the late 1930s, they were just barely getting by. And so, considering all they had done for me, they came to live in Nevada in 1942. I drove back to Ringoes one more time and I brought the folks back with me. My father hoped that perhaps he’d find an orchestra to play with in Reno, but it never happened. And sadly, my father never really played professionally again.”

BACK TO NEVADA

I turned to another page of the journal and read a passage or two to myself. Herb’s hearing is not much

better than his eyesight these days and he had leaned his ear close to me as I recited from his father’s words. Now he wasn’t hearing anything at all.

“Let’s stop for a while,” he suggested. “I’m hungry. How about some dinner?”

I nodded. Herb went to the refrigerator, pulled out a pan of pound cake, a quart of strawberries, and a can of whipped cream. “If you don’t mind,” he said, “let’s just go straight to the dessert tonight.”

“We’re kindred spirits in more ways than I ever dreamed possible,” I answered. “We’re two divorced guys trying to prove we can live a healthy and active life eating nothing but junk food. But you have about a 40 year lead on me, Herb.”

“I didn’t get all of that…miserable hearing aid,” Herb grumbled, “but I got most of it…don’t you want some more whipped cream on that?”

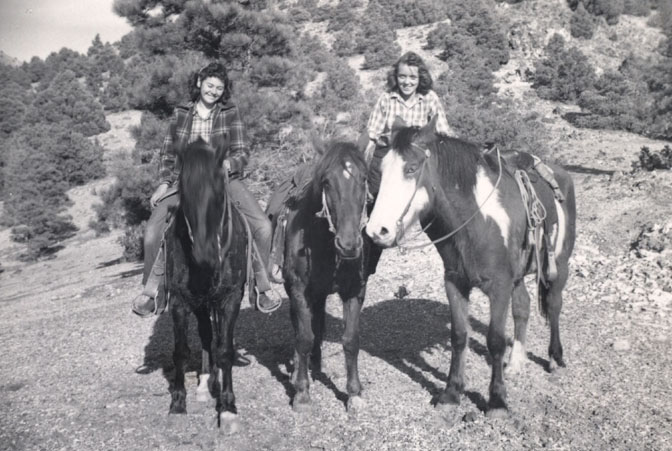

In many ways Herb began life all over again when he made the move to Nevada. And for Herb’s mother and father it was a whole new world. Except for the summer trips to Colorado Springs when Herb was a small boy, the Ringers had not ventured farther west than Cincinnati. Now suddenly Joseph and Sadie Ringer were making a new home in one of the wildest and most remote parts of the American West.

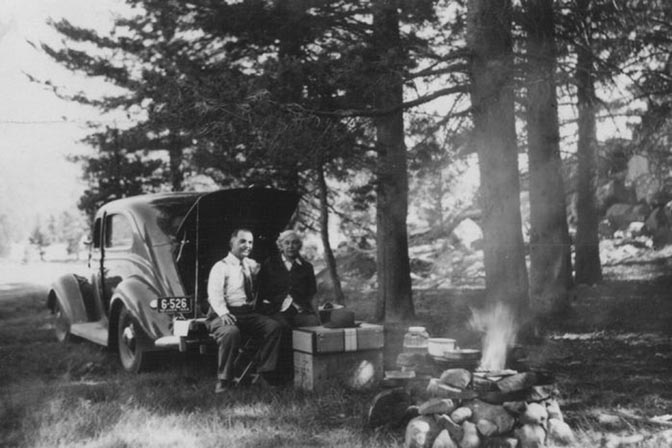

Until 1942, neither of Herb’s parents had ever camped out a day of their lives. Herb changed all that. The parents scarcely had time to unpack before Herb bundled them into his Ford and took them for a day trip to Virginia City. It would be the first of thousands of journeys, both short and long, to the remote and hidden corners of the West. In order to make ends meet, Mr. Ringer went to work at the Washoe Market with Herb who was by now the store manager. Even Sadie helped out during busy times. They worked six days a week, month after month. But they never seemed to squander a moment of their free time.

One of Herb’s first Kodachrome transparencies. 1946

On Saturdays, after locking up the market for the weekend, the Ringers hit the road. Herb had specially equipped the Ford so that his parents could sleep across the back seat. He pitched a canvas tent for himself and with a cook box and stove that he permanently kept in the trunk, the Ringers camped out almost every Saturday night (weather and season permitting) for years. They explored ghost towns in the Nevada desert and searched for the remains of the long abandoned Virginia & Truckee Railroad. In the summer they sought the cool relief of the High Sierras and, according to Herb’s own count, made 120 trips to their favorite mountain getaway, Hope Valley. But their first overnight sojourn to Hope Valley, in June 1945, gave them more escape from the heat than they had in mind. Herb’s father faithfully recorded the day…

“June 5, 1945: Herb took us up to Hope Valley, Calif. to camp out there overnight for the first time. It was cold so we built a big fire and stood around it until it was time to go to bed. We all slept in the car & when we got up in the morning there was ice in our pots. It was 22 degrees. Where we slept it was over 7000 feet. It turned out to be a fine day and it got up to 82 degrees.”

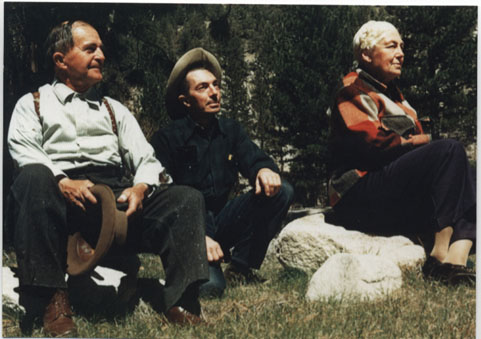

And that is how Herb and his parents lived for much of the next 20 years. In addition to their weekend wanderings, they traveled to the Rocky Mountains, to the Pacific Northwest, to California, to Alberta, Canada, and sometimes back east to New Jersey to re-establish contact with the family. But they always seemed ready to travel whenever the opportunity presented itself. Even his mother, who by the time they made the move to Reno was in her 60s, adapted remarkably well to the outdoor life. Herb always marveled at the way Sadie embraced camping and endured the lack of amenities. “I never heard her complain.”

The Ringers owned a succession of vehicles. They sold the ’36 Ford in 1945 and bought a ’41 Lincoln Zephyr. And then a ’46 Ford. And a ’49 ‘Woodie.’ And a ’54 Ford pickup with one of the first camper shells ever made. They crisscrossed the West, again and again and traveled hundreds of thousands of miles in a part of America that was still asleep and undiscovered.

And Herb kept taking pictures. From the beginning, he used 35mm cameras with excellent optics and later purchased a large-frame (2 1/4 inch) camera. When Kodak introduced its Kodachrome color film in 1946, Herb was one of its first customers and used it exclusively. Occasionally he’s turn to Agfachrome, an “awful product” Herb said later. “The color went bad within a few years.” (Herb would be delighted to know that thanks to modern technology and PhotoShop, I’ve been able to color-correct many of those tarnished transparencies.)

Herb photographed the mountains and the deserts and the canyons. But he also photographed the small towns, the gas stations, the cafes, the road houses, and the people he met along the way. He created a portfolio of life in the West in the last years before Industrial Tourism grabbed it by the throat. His work is testimony and tribute to another time.

the first of many trips. 1952.

Herb took this color image with his Rolleiflex 2 1/4 camera in the late 1950s.

ANOTHER LIFE CHANGE & LOSS …ON HIS OWN

In 1963, Herb’s father was diagnosed with cancer and his health failed more rapidly than they could have imagined; Herb spent most of his life savings, trying to save his father’s life. The family had accumulated $37,000 in a lifetime of hard work. It was gone in months. Joseph Ringer died later in the year.

Just a year later, in 1965, Medicare was enacted but it came too late for the Ringers. Still, Herb and his mother continued to travel, albeit on a shoestring budget, to places as far away as the Canadian Rockies, even though Sadie was now in her late 80s. In July 1974, while at Banff National Park in Alberta, Herb suffered a massive heart attack. As he was being rushed by ambulance to a nearby hospital, the shock of seeing Herb unconscious and in critical condition was too much for his mother. Sadie was struck down by a cerebral hemorrhage; while Herb’s heart slowly healed, Sadie died a few weeks later. She was 92 years old. Herb had just turned 61.

Herb was devastated by the loss and discouraged by his own health problems. But one morning he arose from bed, looked out the window at the beautiful fall day that awaited him and decided he would not let his heart attack or the grief that still gripped him ruin the remainder of his life. “It was simply a case of mind over matter,” Herb recalled.

RETIREMENT & THE OPEN ROAD

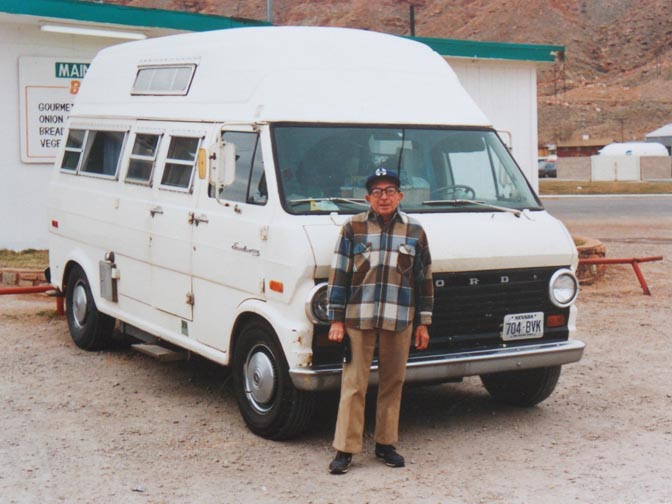

He retired from his grocery job, re-located the trailer to Fallon, sixty miles southwest of Reno, and determined to make the most of every remaining day of his life. Now he would spend every possible moment exploring the West that he loved so much.

A routine, if you can call it that, began to emerge. He started packing up his 1970 Ford Econoline Camper late in January of each year. By the first week of February, Herb was ready to travel. He always headed south for warmer weather and stayed at that latitude until spring. Sometimes he journeyed all the way to the east coast; sometimes he’d only go as far as the midwest. But he was almost always back in his beloved Colorado by June.

In the winter of 1986, I suffered the devastating loss of a friend. We had planned to visit Herb in January. Now my life was in pieces. I wrote to Herb and gave him the awful news. He knew her too and was heartbroken. There wasn’t time for him to even reply. Herb loaded up the Econoline in late January and headed for Moab to be with me. He parked his van in my front yard and stayed with me for over a week. Finally, I urged him to go south to Arizona and warm up. He reluctantly agreed and gave me a hug. Then as he turned to go, he handed me a small paper bag. “I know these might not mean anything to you now, but I want you to have them.”

I nodded absently and watched Herb drive away. I took the paper bag and shoved it in the back of a dresser drawer. I forgot all about it. I knew this would be my last year working at Arches, but I spent one more season at the Devils Garden. In September Herb wrote to tell me I’d be seeing him soon. The letter jogged my memory. — thet bag. I found it where I had left it and was dumbstruck. It was a bag full of Kodachrome slides, some going back to the 1940s. I need to explain that while I knew Herb love to take pictures, I had until this moment never seen the product of his efforts. Nor did it sink in that he had been using Kodachrome film since the late 40s. When he arrived I was overwhelmed and we poured over every photo, every memory.

Herb kept coming to Moab, and he still stayed at the Devils Garden Campground along with his Burmese cat, Nami. He became a part of my routine as well. I could not imagine an April or an October without Herb. Once in 1995, I got a hastily written note from Herb; he feared he would most likely miss our annual rendezvous. Early in the summer, he had experienced some worrisome health symptoms and immediately drove himself back to Fallon. Herb was diagnosed with colon cancer and underwent major surgery the next day. A couple of weeks later, Herb wrote again to let me know he had survived the operation, but remained skeptical about his prospects. This was major surgery and Herb lived alone. He was worried we’d never see each other again.

But October came and…here came Herb. “Well,” he complained gently, “I already wasted part of my summer. I wasn’t about to let it ruin the entire year.” Mind over matter.

And so the years passed and each visit from Herb brought more stories and pictures and memories. Herb became my Time Machine. I could say to Herb, “OK, it’s the summer of 1941 and you’re getting ready to head west again from New Jersey.” And Herb will pause briefly, gather his thoughts and say, “Yes. I remember I left about eight in the morning. It was a clear cool day. Not too hot. I traveled north on Route 22 and stopped for breakfast at a little diner.” It was like that.

In the summer of 1994, I met Herb in Crested Butte, Colorado and we camped by a lake near Kebler Pass. But something wasn’t right and Herb was worried. Without any warning, his eyesight had begun to deteriorate. He had recently been to an opthamologist who saw no problem so it seemed unlikely that his vision could go so rapidly. But Herb was concerned enough to cut his summer trip short. He insisted he could still see well enough to drive and so we reluctantly watched him take to the road again in his camper.

By the time he reached Fallon, he could barely make out the road. And an eye examination brought bad news. Irreversible macular degeneration had robbed Herb of most of his sight and the condition would grow even worse. After more than a million miles, Herb’s driving days came abruptly to a halt. He parked his beloved Econoline Camper and never drove it again.

I could not imagine how Herb would survive this sudden loss of mobility. Traveling was his passion and his life. All his friends lived along thousands of miles of highway, in large cities and small towns across America. He had not spent more than three months at a time in Fallon since he moved there in 1974.

“I CAN STILL SEE EVERYTHING.”

Somehow he adjusted. Herb never drove again after that last drive in 1994. From now on, I would be the traveler and Fallon would be my destination. He learned to live with his failing eyesight better than I dreamed possible. We were also able to find additional public assistance for Herb. He was always such a proud man, and other than his meager social security payments, he had never considered seeking help. We visited the social services office in Fallon and discovered he was eligible for an increase in his benefits, due to his loss of vision. He qualified for food stamps–it had never occurred to him. He was able to get assistance for heating costs and a booster speaker for his phone allowed us to talk long distance for the first time; he had been too deaf to use his phone for several years.

Best of all, for Herb, the social services office assigned a staffer to visit Herb several times a week. The official purpose was to help with meals and cleaning, but the real bonus for Herb was the human contact. Her name was Becky and she became a good friend to Herb, in addition to her official duties. He loved the company. He seemed happy.

During a summer visit in 1996, Herb began to reminisce about his family’s many trips to Hope Valley in the High Sierras. Always the statistician, Herb somehow remembered that he and his parents had made 259 drives to Hope Valley, from that first cold night until his father’s death in 1963. Neither Herb nor his mother could bear to return. But now, all these years later, I asked Herb if he’d be willing to pay one more visit to his old stomping grounds. Herb was delighted. Hope Valley is about an hour west of Carson City, where Herb’s divorce had been finalized so many years before. Though his eyesight was weak, he still managed to point out the courthouse. He just shook his head and said nothing.

An hour later, we reached the very spot where the Ringers had camped. He looked at his old world through blurred eyes, but as he always liked to say, he could “still see everything.” We had brought a picnic lunch and we stayed for a couple hours. He had made his 260th trip to Hope Valley. It would be his last. My first. As we came back into Fallon he leaned over and patted my shoulder. “Thanks for that, Jim….Now I’m going to buy you a steak at the Stockman’s.” It was one of our last dinners out.

Finally, Herb’s health began to deteriorate in the summer of 1997. That winter, I asked Zephyr readers, who had followed Herb’s story and loved his photographs for the last decade, to send Herb a note. I mentioned his recent hard times; the response was overwhelming and Herb was overwhelmed. When I visited him in the new year, his little trailer was decorated with the dozens of cards and notes he had received. He could no longer read them, but Becky served as “translator.” It really boosted his spirits.

But that following summer, Becky had to quit her job. Her husband had been transferred away from the area. Herb was crushed. Social services sent a replacement, but it wasn’t the same. I drove to Fallon in late July and it was clear he was in rapid decline. Finally, in August, Herb moved into a retirement center; he was almost blind from the macular degeneration and he felt he had no other choice. But I feared that Herb would lose his identity, if he walked away from the old Smoker trailer he bought in 1952. But what were his options? Within weeks, his physical and mental health failed rapidly. For a man whose memory meant everything to him, Herb must have felt like an alien to himself, as the history of his life ebbed away.

In late November, I spent some time on the phone with Herb’s doctor. Though there was no immediate cause for alarm, it seemed to him that Herb had lost the will to live. I called Herb and we spoke briefly; then I realized —he didn’t know who he was talking to. The next morning, I was having coffee with my pal, Bill Benge. I was talking about Herb, who Bill had met many times.

“You know,” I said, “I think Herb is going to die on my birthday.”

Bill looked startled. “Why would you say that?”

I shrugged. “Don’t know. Just a feeling, I guess.”

But the feeling didn’t go away.

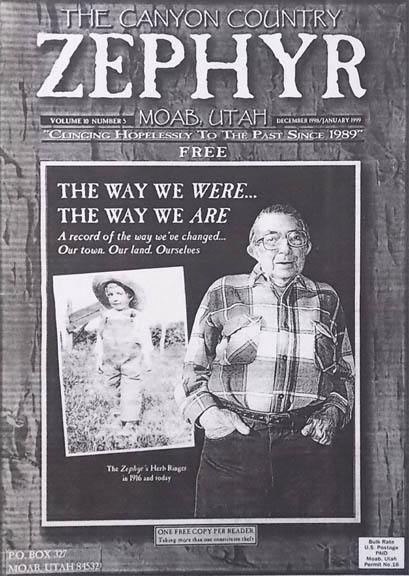

The next Zephyr press day was December 11, and I’d already planned an issue called, “Then and Now—the way we were, the way we are.” On the cover were two pictures of Herb. The first was a childhood image, taken by his father in 1917. The second was one of my own, shot the previous August when I helped him move.

On the morning of the 11th, I made the two hour drive to Cortez, Colorado, where The Zephyr was printed for 14 years. All day I was haunted by premonitions. In the early afternoon, I loaded the last of the copies into the truck and raced back to Moab, convinced I’d find a sad message on my answering machine when I got home.

But when I walked in the door, the blinking red message light was dark. I breathed a sigh of relief and walked up to Dave’s Corner Market for a cup of coffee. An hour later I came home to the blinking light I’d been dreading.

Herb had died at 2 pm.

That afternoon, I contacted the hospital and then the retirement home. A wonderful woman there, an RN named Patty Lee, had taken a personal interest in Herb; she helped me deal with all those “arrangements” that have to be made, when we are least capable of dealing with anything at all but our own grief

A few days later, I had the most remarkable dream….

I was standing waist-deep in a swift clear mountain stream, but safely in the shallows and out of the current. Floating on his back in front of me and looking perfectly serene was Herb. Only my firm grip on his shoulders kept him in the backwater.

The banks were green and lush but midstream granite boulders disrupted the water’s flow and created eddies and swirls. It looked dangerous to me, but Herb wanted me to push him into the current. I argued with him, insisted it was too risky, but he just nodded and smiled.

“It’ll be okay, Jim…just give me a push.”

I hesitated again and he put his hand on mine and patted it.

“Okay Herb.”

I reluctantly released my grip and as he floated by me, feet first, I gave his shoulders one last push. The current grabbed him almost instantly and I watched Herb enter the heart of the stream. But as he passed one of the granite boulders, Herb was snared by an eddy and I watched with alarm as he spun in small circles near the rock.

“Herb!” I cried out. “Are you alright?”

But no sooner had I called out to Herb, the eddy released him into the free current. As he floated downstream, Herb Ringer raised one hand and waved goodbye.

That remarkable dream has stayed with me all these years and is as vivid in my mind’s eye now as it was then. I’ve never known such clarity, in the image of the dream or its meaning. I still feel good about it.

*****

All these years later, Herb, via our times together and the photographs and stories he left me, never seems far away. And one more time, I would swear he stopped by to say hello.

I have spent countless hours over the last two and a half decades, reviewing and scanning Herb’s photographs and re-reading his journals. One afternoon, he seemed determined to let me know he was still around.

In 1998, as Herb prepared to sell his trailer and move to the retirement home, I became the recipient of many of Herb’s treasures. Among them is a beautiful Swiss-made clock that had been in the Ringer family for decades. He presented it to me one day, carefully showing me how to wind it with the brass key he kept hidden in its base. “Not too tight,” he warned. He advanced the hour hand to the twelve o’clock position so I could hear the chimes. “Lovely,” he said.

We carefully wrapped it in a cotton sheet and placed it in a box for the trip back to Moab. I set it on my bedroom dresser and for years I fell asleep nightly to the tick-tock of Herb’s clock and its hourly chimes.

Then one day, it stopped. I thought maybe I’d forgotten to wind it, but no…the clock quit ticking. I searched unsuccessfully for a clock repair person who might be able to revive my beloved Herb Clock, but finally gave up. It was still a beautiful contraption, even without its ticks, so I took comfort in just looking at it and remembering all the memories contained within it. A decade passed.

Then one afternoon, it started ticking again. I walked to my dresser to dump some loose change and heard an almost familiar sound— and could not believe my ears. Or eyes. The pendulum was swinging back and forth, as it always had. The familiar tick was back. And that night, it chimed. A few days later, it stopped once more. And never ticked again.

I’m not quick to believe in the Otherworldly, but on this occasion I’d prefer to. I’d love to believe that Herb dropped by, gave his beloved clock a tap in just the right spot, and silently chided me, “I told you not to wind it too tight.”

I wish he was still here saying, “I can still see everything.” Friendships like ours should last forever. Maybe they do.

To find all of Herb’s Zephyr stories and pictures, going back many years, click here.

To comment on this story, scroll to the bottom of this page

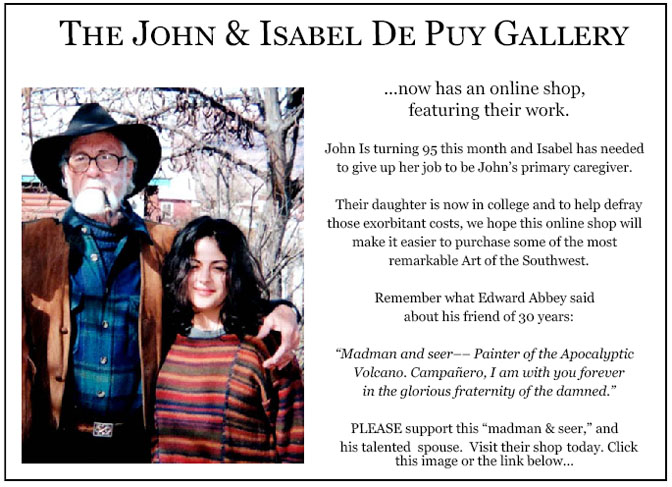

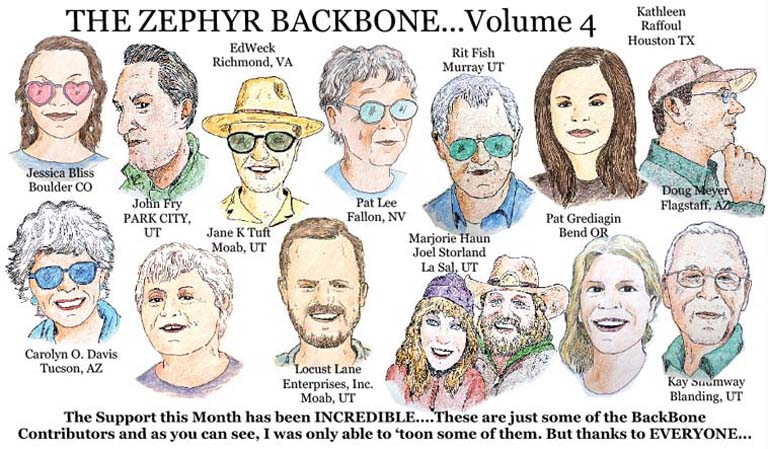

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

We post at least twice a day on our Zephyr Facebook page, including many photographs from Herb Ringer and Edna Fridley

Remarkable indeed! I long for the West as Herb Ringer chronicled it.

It’s a wonderful article, Jim. Herb Ringer really was a nice man. Always with a smile for me and never in a hurry. I remember him from the 70’s- my last season at Arches was 1981.

Good man and good article, thanks so much!

Oh Jim, what a beautiful story. Herb was a special man. I am so pleased to have know him for a short time. I was the secretary at the retirement home. Will this be a book or is it now. I would love to buy a copy or i goes i could print this out.

Blessings to you.

Jim I sat at my computer desk this Monday morning and read carefully through this article about Herb. No just scanning like I often do on less interesting material. I was really intending to read something else but this article drew me right in. I guess partly because I have lived from the days that you and Herb describe in the old west to what we see today. Your comments about dreams and maybe continuing your friendship with Herb at another place fit in with my experiences and faith. Keep up the good work.

Excellent read Jim excellent. I could sit for hrs and listen to older generation and the stories they had to tell

Another great piece about about a man whose collection of a lifetime’s photos and notes is a valuable look at the past. Where will we find the letters and photos of the present time in the future when they will be hidden and/or locked away in someone’s computer or cell phone? Long live the pen and photos! (Says the guy typing away on his computer.)

Sweet–gotta love Herb’s photographs. I was struck by the fact that you met Herb in the Devils Garden Campground in the Fall of 1981. I was camped there myself in late September 1981. New room-mates in Boulder had recommended that I visit Arches. I had just spent a night sleeping on a picnic table at the cliff edge of Dead Horse Point and had awoken to the most glorious sunrise of all time. So it may be that I actually met Ranger Jim Stiles collecting campground fees. I wouldn’t have been half as interesting a fellow to meet in September 1981 as Herb Ringer!

Thanks, Jim, for your remembrance of Herb and his family. Being a young man (67), I didn’t get to know him, but I felt like I did after reading your account of his life. How the west, and it’s people, have changed, even during my short time here (I arrived in the ’70’s). It’s a great feeling to hear stories of the older generation, and to honor their memory.

Loved the Herb Ringer story! Thank you for sharing!

I never tire of Herb stories and the accompanying photos. But this has got to be the best, or one of ’em. I love the clock story. Thank you Jim. And thank you Herb.

What a beautiful friendship and a remarkable story.

Speaking of clock I would implore you to listen to the song “My Grandfathers

Clock” by Jim Stiles….it will tug your heart

Lastly I kept thinking throughout that Abbey would make an appearance?

Had they met to your knowledge.?

Thank you!.

Duh …aforementioned folk singer (myGrandfather’s Clock) was

Jim Staines… sorry for the error

Thanks for keeping him and his photographs alive! Always enjoy reading and experiencing his art.

What a guy! Devotion like his to his parents is so rare! What a life he gave them, the adventures, the camping experiences! And he filled in the void his father felt with the loss of his musical career. Plus he left a written and photographic record of a world no one will ever know again. How great that he had a friend like you, faithful and interested in the same things ! And who knows, that little vase-like gadget may really be from King Tut’s larder!!

It’s hard to describe the pleasure I’ve felt from reading your stories about Herb Ringer and his love of the West. Your touching descriptions of Herb and his life keep his memory alive, and along with all of his photos and recollections we can know him through your excellent writing abilities.

I first experienced the West in 1954. My parents had moved us to California. During my school years, we lived in the Bay Area (Hayward, Niles-Fremont), the San Joaquin Valley (Stockton, Auburn, Delano), the Mohave Desert (Lancaster), and then in Carson City, Nevada. We explored, picnicked, and camped around all of those areas. Just as Herb did, I loved the West. In 1963 when I graduated from Carson High School I remained in the area until about 1973. When my wife and I were first married we lived in a trailer park on Zolezzi Ln, off South Virginia St in Reno. We received our mail from the post office in Steamboat, NV. I could easily have met Herb during my Nevada years and I think I would have loved being his friend as you did. Just as a commenter above mentioned, it’s always been a pleasure of mine to hear the life experiences of preceding generations.

Jim, you were a kind and loving friend to Herb, just as a son might have been. Helping him in his last years, not only with your visits but also with helping him find personal and financial assistance that improved his remaining life.

Thanks Jim, you were such a good friend to him.